Randomized trial of 1-week versus 2-week intervals for endoscopic ligation in the treatment of patients with esophageal variceal bleeding

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (P30 DK34989, L.L.).

Abstract

The appropriate interval between ligation sessions for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding is uncertain. The optimal interval would provide variceal eradication as rapidly as possible to lessen early rebleeding while minimizing ligation-induced adverse events. We randomly assigned patients hospitalized with acute esophageal variceal bleeding who had successful ligation at presentation to repeat ligation at 1-week or 2-week intervals. Beta-blocker therapy was also prescribed. Ligation was performed at the assigned interval until varices were eradicated and then at 3 and 9 months after eradication. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with variceal eradication at 4 weeks. Four-week variceal eradication occurred more often in the 1-week than in the 2-week group: 37/45 (82%) versus 23/45 (51%); difference = 31%, 95% confidence interval 12%-48%. Eradication occurred more rapidly in the 1-week group (18.1 versus 30.8 days, difference = −12.7 days, 95% confidence interval −20.0 to −5.4 days). The mean number of endoscopies to achieve eradication or to the last endoscopy in those not achieving eradication was comparable in the 1-week and 2-week groups (2.3 versus 2.1), with the mean number of postponed ligation sessions 0.3 versus 0.1 (difference = 0.2, 95% confidence interval −0.02 to 0.4). Rebleeding at 4 weeks (4% versus 4%) and 8 weeks (11% versus 9%), dysphagia/odynophagia/chest pain (9% versus 2%), strictures (0% versus 0%), and mortality (7% versus 7%) were similar with 1-week and 2-week intervals. Conclusion: One-week ligation intervals led to more rapid eradication than 2-week intervals without an increase in complications or number of endoscopies and without a reduction in rebleeding or other clinical outcomes; the decision regarding ligation intervals may be individualized based on patient and physician preferences and local logistics and resources. (Hepatology 2016;64:549-555)

Abbreviations

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

Esophageal variceal bleeding is associated with higher rates of rebleeding and death than other common causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.1 Despite advances in treatment, approximately 25% of patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding have persistent bleeding or recurrent bleeding within 6 weeks.2 Furthermore, the risk of death or complications is also highest in the first 6 weeks after presentation.2 Therefore, goals of therapy are to stop bleeding and prevent recurrent bleeding to reduce the risk of bleeding-related complications and deaths.

Current guidelines recommend treatment with endoscopic ligation plus a nonselective beta-blocker to prevent recurrent esophageal variceal bleeding after the acute episode of variceal hemorrhage.1, 3 Endoscopic ligation is performed at regular intervals until the varices are eradicated. US guidelines suggest ligation for secondary prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding be performed at 1-week to 2-week intervals1 and at 1-week to 8-week intervals4 but indicate that prospective trials are needed to determine the optimal interval.4

Two randomized comparisons of 1-week versus 3-week intervals with sclerotherapy suggested that 1-week intervals may be preferable because varices were eradicated significantly more rapidly, rebleeding was less frequent, and there were no significant differences in complications or deaths.5, 6 Given that ligation causes less local injury than sclerotherapy, ligation should be at least as good or better when assessing a 1-week interval versus longer intervals. Ideally the optimal interval would provide rapid eradication in order to lessen early rebleeding while minimizing complications. This should be achieved by identifying the shortest interval that does not appreciably increase ligation-induced adverse events.

We performed a prospective randomized study to determine the appropriate interval for endoscopic ligation therapy in patients who presented with acute variceal bleeding. Because available studies in sclerotherapy suggested that 1-week intervals might be preferred and because the US guidelines at the inception of the study suggested intervals of 1-2 weeks, we chose to compare 1-week and 2-week intervals. Our primary hypothesis was that 1-week intervals would lead to more rapid eradication of esophageal varices compared to 2-week intervals.

Patients and Methods

STUDY DESIGN

Patients who underwent endoscopy for acute esophageal variceal bleeding and received successful endoscopic ligation therapy at Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center were eligible for enrollment into this prospective randomized controlled trial. Exclusion criteria included prior esophageal variceal endoscopic therapy within 1 year, previous transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt or surgery for treatment of portal hypertension, use of sclerotherapy during the index bleeding episode, platelet count <40 × 109/L, or incarcerated patients.

ASSIGNMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

At 1 week after their index variceal bleeding episode patients who met enrollment criteria were randomly assigned by an investigator using a computer-generated randomization schedule with concealed allocation to 1-week versus 2-week ligation intervals. The allocation list was generated by an individual uninvolved with study conduct and had opaque coverings over the assignment. Beta-blocker therapy with propranolol 10 mg twice daily was initiated 1 week after the index bleeding episode unless there was a contraindication or the patient refused. Propranolol dose was to be titrated up at subsequent visits with the goal of heart rate <60 beats per minute without hypotension or other side effects. Patients assigned to 1-week intervals received endoscopy 1 week after the index procedure and returned weekly for repeat endoscopic sessions. Those assigned to the 2-week intervals returned for ligation 2 weeks after the index procedure and then every 2 weeks. Endoscopy with ligation was performed until varices were eradicated.

At each endoscopy, prior to any ligation therapy, a gastroenterologist blinded to the patient's treatment group assessed whether the varices were eradicated or not. The blinded endoscopist also assessed for esophageal ulcers and strictures. If banding ulcers were extensive, the ligation treatment session could be postponed and rescheduled at the discretion of the endoscopist who was blinded to treatment assignment. If ligation was postponed, the endoscopy was repeated in 1 week in the 1-week interval group and in 2 weeks in the 2-week interval group. Once varices were eradicated, repeat endoscopy was performed at 3 and 9 months after eradication to determine if varices remained eradicated. If varices recurred, ligation was again performed every 2 weeks until eradication of varices, and a follow-up endoscopy was performed at 3 and 9 months.

Patients were followed 9 months after initial variceal eradication. During follow-up, patients were assessed for interval bleeding episodes; dysphagia, odynophagia, or chest pain leading to unscheduled visits; and subsequent hospitalizations.

STUDY ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint of the study was proportion of patients who achieved eradication of varices at 4 weeks. Additional endpoints included days to variceal eradication; proportion with variceal eradication at 8 and 12 weeks; number of endoscopies required for eradication of varices; rebleeding (within 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks; overall study period; preeradication and posteradication); dysphagia, odynophagia, and/or chest pain requiring unscheduled visits; esophageal strictures; ligation sessions postponed due to ligation-induced ulcers up to the time of eradication or to the last endoscopy if eradication was not achieved; repeat hospitalization; and death.

We do not believe that ligation-induced ulcers are a meaningful endpoint in the absence of complications such as bleeding or symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, or chest pain. Furthermore, because the 1-week group had repeat endoscopy 1 week sooner than the 2-week group, the study protocol ensured that more ulcers would be identified in the 1-week group because patients were examined sooner after ligation. Nevertheless, we did record the ulcers identified by the blinded endoscopist on subsequent endoscopies after the index procedure up to variceal eradication or the last endoscopy if eradication was not achieved. The number of endoscopies required for eradication included endoscopies at which ligation was not performed (e.g., endoscopies at which ligation was postponed, the endoscopy which documented variceal eradication) but excluded the index endoscopy performed at the presentation of variceal bleeding. Rebleeding was assessed beginning 1 week after the index bleeding episode (after randomization) and required overt upper gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., hematemesis, melena) necessitating hospitalization.

ANALYSIS

Given the reported mean of ∼3.5 treatment sessions to achieve variceal eradication,7 our sample size calculation assumed variceal eradication rates of 50% in the 1-week group and 20% in the 2-week group at 4 weeks. With an alpha of 0.05 and power of 80%, 45 patients were required in each group to show a significant difference. Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables with normal distribution or as median and range otherwise. Comparisons of proportional data between the study groups were performed with chi-square or Fisher's exact test where appropriate, and continuous data were compared using the t test. Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were done on an intention-to-treat basis.

The study was approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California, and all patients provided written informed consent. The trial was an investigator-initiated study, and the study protocol was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01291277).

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

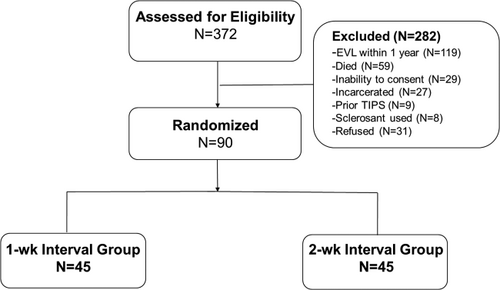

Between August 2008 and December 2014, 372 patients hospitalized with upper gastrointestinal bleeding from esophageal varices were assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1). Overall, 282 patients were excluded, including 119 patients who had received ligation in the prior year and 59 who died during the index hospitalization. Ninety patients were enrolled with 45 randomized to the 1-week and 45 to the 2-week interval groups. Baseline characteristics at the time of index variceal bleeding, units of blood transfused, and duration of index hospitalization were similar between the two groups (Table 1). Propranolol was initiated in 41 (91%) patients in the 1-week group and 43 (96%) in the 2-week group. The mean titrated doses up to the time of eradication or the last endoscopy in those without eradication were 25 ± 7 mg in the 1-week group and 23 ± 6 mg in the 2-week group, and propranolol was discontinued due to side effects by 6 (13%) patients in the 1-week group and 5 (11%) in the 2-week group.

| 1-Wk Interval (n = 45) | 2-Wk Interval (n = 45) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 53 (27-66) | 54 (30-78) |

| Male | 31 (69%) | 38 (84%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Latino | 39 (87%) | 39 (87%) |

| Asian | 6 (13%) | 4 (9%) |

| White | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| Alcohol | 24 (53%) | 24 (53%) |

| Viral hepatitis | 9 (20%) | 12 (27%) |

| NASH | 10 (22%) | 6 (13%) |

| Other | 2 (4%) | 3 (7%) |

| Symptoms | ||

| Hematemesis | 14 (31%) | 12 (27%) |

| Melena | 24 (53%) | 22 (49%) |

| Hematemesis and melena | 7 (16%) | 11 (24%) |

| Hemodynamic instability | 21 (47%) | 23 (51%) |

| Child-Pugh A/B/C | 17/22/6 (38%/49%/13%) | 14/20/11 (31%/44%/24%) |

| Median MELD score | 11 (7-33) | 12 (7-34) |

| Prior gastrointestinal bleeding | 7 (16%) | 7 (16%) |

| Laboratory findings (range) | ||

| INR | 1.4 (1.1-2.5) | 1.5 (1.0-2.8) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.3 (0.3-36.0) | 1.3 (0.4-14.0) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.0 (2.0-4.5) | 3.0 (1.6-4.6) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.4-2.5) | 0.7 (0.8-8.0) |

| AST (U/L) | 51 (15-301) | 52 (15-788) |

| ALT (U/L) | 36 (8-183) | 35 (11-738) |

| Findings at index EGD | ||

| Size of varices | ||

| Moderate | 14 (31%) | 14 (31%) |

| Large | 31 (69%) | 31 (69%) |

| Median number of columns (range) | 4 (1-6) | 4 (1-6) |

| Median number of bands (range) | 5 (1-13) | 5 (1-7) |

| Mean units red cells (range) | 2 (0-4) | 2 (0-8) |

| Median hospital days (range) | 3 (1-13) | 4 (1-22) |

- Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Forty (89%) patients in the 1-week group and 42 (93%) in the 2-week group were followed through the predefined 12-week assessment. In the 1-week group 2 patients died (one had confirmation of variceal eradication) and 3 were lost to follow-up (2 had confirmation of variceal eradication) at 12 weeks, while in the 2-week group 2 patients died (1 had confirmation of variceal eradication) and 1 was lost to follow-up at 12 weeks. In the 1-week and 2-week groups 36 (80%) and 35 (78%) patients completed the planned 9-month follow-up after variceal eradication or died during the study period.

ENDOSCOPIC OUTCOMES

The primary endpoint of eradication of esophageal varices at 4 weeks occurred more frequently in the 1-week group: 37 (82%) versus 23 (51%) (difference = 31%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 13% to 50%) (Table 2). Eradication of varices occurred more rapidly in the 1-week group (18.1 days versus 30.8 days; difference = −12.7 days, 95% CI −20.0 to −5.4) compared to the 2-week group. However, there were no significant differences in proportion of patients who achieved eradication of varices at 8 weeks or 12 weeks. Variceal eradication was not achieved in 3 (7%) patients in the 1-week group (1 died, 1 lost to follow-up, 1 had transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for recurrent variceal bleeding) and 5 (11%) patients in the 2-week group (2 declined to attend study-mandated endoscopy sessions, 1 did not attend study-mandated endoscopies due to incarceration after enrollment, 1 died, 1 lost to follow-up).

| Endpoint | 1-Wk Interval (n = 45) | 2-Wk Interval (n = 45) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eradication at 4 weeks | 37 (82%) | 23 (51%) | 31% (13% to 50%) |

| Eradication at 8 weeks | 42 (93%) | 38 (84%) | 9% (−4% to 22%) |

| Eradication at 12 weeks | 42 (93%) | 40 (89%) | 4% (−7% to 16%) |

| Mean days to eradication (SD) | 18.1 ± 13.6 | 30.8 ± 19.1 | −12.7 (−20.0 to −5.4) |

| Mean number total endoscopies to eradication (SD) | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.8) |

| Mean number endoscopies with ligation (SD) | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 1.2 | 0.0 (−0.6 to 0.6) |

| Mean number endoscopies with ligation postponed (SD) | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.2 (−0.02 to 0.4) |

| Mean number endoscopies with confirmation of eradication (SD) | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) |

| Patients with postponed ligation session | 10 (22%) | 4 (9%) | 13% (−1% to 28%) |

| Esophageal strictures | 0 | 0 | — |

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

The mean number of endoscopies up to the time of variceal eradication or to the last endoscopy in those not achieving eradication was comparable in the 1-week and 2-week groups (2.3 versus 2.1; difference = 0.2, 95% CI −0.5 to 0.8) (Table 2). The mean number of endoscopies is made up of endoscopies with ligation, endoscopies at which eradication was confirmed and therefore no ligation was required, and endoscopies at which ligation was postponed. The mean number of ligation sessions and mean number of endoscopies in which eradication was documented were identical in the 1-week and 2-week groups (Table 2). A higher proportion of patients in the 1-week group had a postponed ligation session (22% versus 9%; difference = 13%, 95% CI −1% to 28%). However, postponed sessions were relatively infrequent in both groups, with the mean number of postponed ligation sessions being 0.3 in the 1-week group and 0.1 in the 2-week group (difference = 0.2, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.4).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

The rates of overall rebleeding as well as variceal rebleeding and ligation-induced ulcer bleeding were similar in the 1-week and 2-week groups (Table 3). Importantly, the incidence of early rebleeding at 4 weeks (4%) and 8 weeks (10%), as well as at 12 weeks (11%), was low in the two treatment groups. Rebleeding during the full study period occurred before variceal eradication in 2 (4%) patients in each study arm (varices in 1 and ligation-induced ulcers in 1 in each study arm). No patients developed esophageal strictures or perforations. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients developing dysphagia, odynophagia, or chest pain requiring unscheduled visits. Three patients in each group died during the study period. Causes of death for all six patients were related to decompensated liver disease or sepsis, and none were attributed to gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Endpoint | 1-Wk Interval (n = 45) | 2-Wk Interval (n = 45) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rebleeding within 4 weeks | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 0% (−9% to 9%) |

| Varices | 1 (2%) | 0 | 2% (−2% to 7%) |

| Ligation-induced ulcer bleeding | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | −2% (−10% to 5%) |

| Rebleeding within 8 weeks | 5 (11%) | 4 (9%) | 2% (−10% to 15%) |

| Varices | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 2% (−5% to 10%) |

| Ligation-induced ulcer bleeding | 3 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 2% (−7% to 12%) |

| Rebleeding within 12 weeks | 6 (13%) | 4 (9%) | 4% (−9% to 17%) |

| Varices | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 2% (−5% to 10%) |

| Ligation-induced ulcer bleeding | 4 (9%) | 2 (4%) | −4% (−15% to 6%) |

| Rebleeding during entire study period | 10 (22%) | 9 (20%) | 2% (−15% to 19%) |

| Varices | 5 (11%) | 5 (11%) | 0% (−13% to 13%) |

| Ligation-induced ulcer bleeding | 4 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 4% (−6% to 15%) |

| Dysphagia, odynophagia, or chest pain | 4 (9%) | 1 (2%) | 7% (−3% to 16%) |

| Subsequent hospitalization | 16 (36%) | 15 (33%) | 2% (−17% to 22%) |

| Death | 3 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 0% (−10% to 10%) |

Discussion

We performed a prospective randomized trial to determine the appropriate endoscopic ligation interval in patients who presented with bleeding esophageal varices and had successful hemostasis after initial ligation therapy. We found a significant 31% absolute increase in the proportion of patients who met the predefined primary endpoint of achieving eradication of esophageal varices at 4 weeks in the 1-week compared to the 2-week interval group. Furthermore, eradication of varices occurred approximately 2 weeks sooner in the 1-week group, without a significant increase in adverse events. Although postponement of ligation at endoscopy tended to be more common in the 1-week group, it was relatively infrequent in both groups and did not lead to a greater number of endoscopies in the 1-week group. The mean number of endoscopies, including endoscopies in which ligation was postponed, was comparable in the two groups. We did not identify differences between 1-week and 2-week intervals in clinical endpoints of rebleeding, subsequent hospitalization, and death. Although we did not formally assess costs in this study, given that the total number of endoscopies and the clinical outcomes, including subsequent hospitalizations, were similar, we would not expect a significant cost difference between the 1-week and 2-week groups.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend repeating ligation of esophageal varices after initial control of bleeding at 1-week to 2-week intervals,1 while the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines suggested 1-week to 8-week intervals.4 However, these recommendations are based on older randomized trials of sclerotherapy, intervals employed in prior ligation trials, and retrospective observational studies of ligation.1, 4 Randomized trials specifically evaluating intervals for secondary prevention with ligation in patients with bleeding esophageal varices are sparse.

A randomized trial from Japan comparing bimonthly and biweekly ligation in 63 patients revealed no differences in eradication, adverse events, bleeding, or death, although variceal recurrence was more common with biweekly ligation. However, this study was not relevant to the question of intervals for secondary prevention in patients with variceal bleeding because 84% of patients received ligation for primary prophylaxis.8 The lack of generalizability to secondary prevention is evidenced by the extremely low risk in the Japanese study's population: the authors reported no bleeding in any patient over a mean follow-up of approximately 2.5 years.

More recently, a randomized trial of 2-week versus monthly ligation intervals for secondary prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding was performed in 70 patients from a veteran's hospital in Taiwan.9 Mean time to eradication was 1 month less in the biweekly group, but this difference was not significant (P = 0.18); furthermore, no significant differences were found in rebleeding, ligation-associated symptoms, or mortality. The results of this study suggest that 2 weeks is an acceptable interval for ligation with no significant increase in clinical adverse events. Our study documents even more rapid eradication of varices with 1-week intervals, without significantly greater adverse events or an increase in the number of endoscopies required to achieve variceal eradication.

The goal of more rapid eradication is to decrease the rate of recurrent variceal bleeding during the critical weeks immediately following the index variceal bleeding episode. Given that the risk of rebleeding, complications, and death are highest in the first 6 weeks after the index bleeding episode and that rebleeding increases the risk of other complications and death, achieving variceal eradication as quickly as possible has been a goal of endoscopic therapy. Nevertheless, concern over ligation-induced adverse events has counterbalanced this desire for rapid eradication, leading many endoscopists to increase the interval between ligation sessions with the goal of avoiding side effects and the need to cancel ligation sessions due to ligation-induced ulcers. Current US guidelines chose to balance these conflicting goals by advising a range of 1 week (given sclerotherapy randomized trials suggesting potential for better outcomes with 1-week intervals) to 2 weeks or more (given concern about side effects and postponement of procedures with shorter intervals).

Our trials did not show a difference in early rebleeding in the 4-8 weeks after the index bleeding episode, which is the ultimate goal of more rapid variceal eradication. Our sample size was calculated to demonstrate a significant difference in our primary endpoint of variceal eradication. This endpoint was chosen based on the premise that if the 1-week interval had more rapid eradication without increased safety or economic concerns, it would be the preferred interval given the presumed association of more rapid eradication with decreased rebleeding. Rebleeding rates were very low at 4 weeks (4%), 8 weeks (10%), and 12 weeks (11%) in our study. Documenting a significant difference in early rebleeding would require an extremely large multicenter study given this low incidence of early rebleeding. Therefore, we may have failed to demonstrate a benefit in early rebleeding due to a type 2 error (insufficient sample size). Alternatively, we cannot rule out that recent improvements in the management of patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding have decreased early rebleeding and lessened the potential benefit of more rapid eradication of varices. Rebleeding in our study population also may have been lower because randomization occurred 1 week after the index bleeding episode. Patients excluded during this 1-week period (e.g., due to death, inability to consent) may have been at higher risk for early rebleeding, and ∼80% of our study population had a Child-Pugh classification of A or B.

Another limitation of our study, similar to most studies of endoscopic intervention, is the lack of blinding. Blinding of endoscopists performing ligation is not possible. Blinding of patients and investigators not performing ligation would have required that all patients undergo weekly endoscopy with sham therapy given at every other endoscopy in the 2-week interval group. We felt the additional risk of sham endoscopies in decompensated cirrhosis patients was not acceptable. However, the assessment of our primary endpoint, variceal eradication, and the decision to proceed with ligation or postpone ligation at each endoscopy were made by an endoscopist blinded to the patient's treatment group to minimize bias as much as possible.

In conclusion, when performing ligation for the prevention of recurrent esophageal variceal bleeding, 1-week intervals led to more rapid eradication of varices than 2-week intervals without an increase in complications or number of endoscopies and without an improvement in clinical outcomes such as rebleeding. Providers and patients may use our data to assist in making choices regarding their ligation schedules. Decisions regarding ligation intervals may be individualized based on patient and physician preferences as well as local logistics and resources.