Racial disparity in liver disease: Biological, cultural, or socioeconomic factors†

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

Chronic liver diseases are a major public health issue in the United States, and there are substantial racial disparities in liver cirrhosis–related mortality. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most significant contributing factor in the development of chronic liver disease, complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. In the United States, African Americans have twice the prevalence of HCV seropositivity and develop hepatocellular carcinoma at more than twice the rate as whites. African Americans are, however, less likely to respond to interferon therapy for HCV than are whites and have considerably lower likelihood of receiving liver transplantation, the only definitive therapy for end-stage liver disease. Even among those who undergo transplantation, African Americans have lower 2-year and 5-year graft and patient survival compared to whites. We will review these racial disparities in chronic liver diseases and discuss potential biological, socioeconomic, and cultural contributions. An understanding of their underlying mechanisms is an essential step in implementing measures to mollify racially based inequities in the burden and management of liver disease in an increasingly racially and ethnically diverse population. (HEPATOLOGY 2008;47:1058–1066.)

Chronic liver diseases are the 12th leading cause of death in the United States and the burden of disease has been projected to increase substantially in the next several decades. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common disorder leading to liver transplantation, and its late-stage complications are expected to result in increased hospitalizations and morbidity. For conditions such as hepatitis C, optimal medical management early in the course of disease can halt the progression to end-stage liver disease. A sentinel report from the Institute of Medicine in 2003 reported racial disparities in healthcare utilization and quality of care for a broad spectrum of chronic diseases.1 In the past 40 years, African Americans have experienced higher age-adjusted mortality rates from liver cirrhosis than whites, a pattern which has been observed more recently in Hispanics.2, 3 Among liver diseases, racial differences in disease presentation, response to medical therapy, use of life-saving liver transplantation, and posttransplant outcomes have been reported. We will provide an overview of these disparities and discuss their potential underlying biological, cultural, and socioeconomic mechanisms.

Defining Health Disparities

The National Institutes of Health have defined health disparities as “differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of diseases and other adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the United States.” These inequalities may occur among different races and ethnicities, gender, geographic regions, those with disability, or socioeconomic status. Racial disparities have become an emerging issue following the pivotal report, Unequal Treatment, in which the Institute of Medicine documented consistently lower level of quality of care and clinically indicated health resource utilization among minority populations with consequent negative impact on health outcomes. These inciting findings were in the context of shifting demographics in the United States. It has been projected that beyond 2050, more than half the nation's population will comprise minority populations. The morbidity and mortality burden that liver disease imparts on specific racial and ethnic groups is a function of the prevalence of that disorder in a given minority population and the health outcomes these subpopulations experience. The latter is in turn influenced by the healthcare process, the provider approach to the patient, and inherent response to treatment. We will explore these various aspects of prevalence, healthcare utilization, and therapeutic outcomes in chronic liver diseases among different races and ethnicities.

Abbreviations

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IDU, injection drug use; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; SVR, sustained virological response; UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing.

Racial Disparities in the Prevalence of Chronic Liver Diseases

HCV and alcoholic liver disease are the leading causes of chronic liver disease in the United States, and nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFLD) disease is an emerging source of liver-related morbidity. There is consistent evidence, particularly for HCV, that the burden of disease is greater in minority populations.

Viral Hepatitis.

Chronic viral hepatitis and its long-term sequelae impose substantial morbidity and mortality that is rising in the United States. Cross-sectional data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 1988 and 1994 (NHANES III) showed that African Americans had more than twice the seroprevalence of HCV compared to non-Hispanic whites (3.2% versus 1.5%).4 This racial difference persisted nearly a decade later in a subsequent NHANES study between 1999 and 2002.5 Racial differences were even more pronounced among U.S. military recruits in which HCV seropositivity was observed in 1.8% of African Americans compared to 0.07% of whites.6 Interestingly, in the NHANES 1999-2002 study, the higher prevalence of HCV among African Americans was almost entirely attributable to older individuals; the prevalence among those younger than 40 were similar between whites and African Americans (1.1% versus 1.2%; P = 0.73).5 This finding may suggest that the persistent racial disparities in HCV prevalence may be due to a cohort effect as those infected in earlier decades age, and that perhaps disparities in new cases are narrowing.

Data from NHANES III also showed that African Americans were more likely to be infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) than were whites (11.9% versus 2.6%) while there was no difference between Hispanics and whites.7 Though nationwide prevalence of HBV among Asian Americans was not captured in the NHANES survey, local screening programs estimate that between 9% and 15% of Asian Americans were chronically infected with HBV.8, 9 Though no direct comparisons were made with white populations, these data suggest that HBV prevalence is higher in Asian Americans than the white population. The high burden of HBV among Asian Americans was most likely due to high prevalence among immigrants from Asian countries where chronic infection is endemic; these individuals had nearly 20-fold higher risk of being chronically infected with HBV than Asians born in the United States.8

The underlying cause for differences in the burden of viral hepatitis among races and ethnicities remains to be defined. The greatest risk factor for acquiring HCV infection is injection drug use (IDU) (odds ratio [OR], 49.6; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 20.3-121.1) which accounts for 60% of all newly acquired cases.10 However, a nationally representative survey found that since the 1950s, African Americans have had a statistically significant 2-fold lower lifetime prevalence of IDU than whites (0.8% versus 1.7%).11 The higher prevalence of chronic HCV in African Americans despite lower rates of IDU may be explained by a higher likelihood of developing chronic infection after exposure. Data from a Baltimore-based prospective cohort study of injection drug users with HCV suggest that following acute seroconversion, African Americans were considerably more likely to develop chronic infection (95% versus 33%).12 Thus, biological susceptibility may play a role in the disparities of HCV prevalence.

Alcoholic Liver Disease.

The prevalence of alcohol abuse among racial and ethnic subpopulations has been less consistently characterized than it has been for HCV. A series of nationwide household surveys suggest that the proportion of incident cases of heavy drinkers in the United States between 1984 and 1992 was highest among Hispanics, followed by African Americans and then whites.13 A subsequent analysis from 1984-1995 showed that nationwide declines in heavy alcohol consumption were different with respect to race. Whereas the prevalence of heavy alcohol drinking decreased among white men (20% to 12%) and women (5% to 2%) during the period, it remained unchanged for African American men (15%) and women (5%). Similarly, a reduction in heavy alcohol use was not observed in Hispanic men (17% to 18%) and women (2% to 3%).14 In contrast, data from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Study suggest that heavy alcohol consumption (>5 drinks/day) did not vary significantly by race or ethnicity.15

There are several lines of evidence suggesting that African Americans who consume alcohol have greater liver enzyme elevations than whites. A population-based cross-sectional study of 3,304 New York residents showed that concentrations of gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) were higher for African Americans than whites within all categories of drinking status (that is, lifetime abstainers and former and current drinkers) after adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic confounders. Racial differences in mean GGT values were more pronounced with increasing amounts of alcohol consumption.16 Another nationwide cross-sectional study found that African Americans and Mexican Americans were more likely to have 2-fold elevations in both GGT and aminotransferases than whites. These racial and ethnic differences were again most amplified among the highest-frequency drinkers.17

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

NAFLD is a rapidly emerging etiology of chronic liver disease. In a cross-sectional study of 159 newly diagnosed NAFLD cases, there was a disproportionately high number of Hispanic patients with NAFLD (28%) relative to their composition in the regional general population (10%).18 Conversely, whites (45%) and African Americans (3%) were underrepresented among the NAFLD cohort compared to their prevalence in the general population. Because factors such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity are predisposing factors for the development of NAFLD, cultural factors such as diet and biological susceptibility may contribute to the higher relative prevalence of NAFLD in Hispanics. The relatively low representation of African Americans among the NAFLD cohort is somewhat unexpected because African Americans, particularly females, have a disproportionately high prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity.19 These findings may reflect underdiagnosis of NAFLD in the African American population or a reduced biological susceptibility to the condition. A retrospective study of morbidly obese patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery also suggested that African Americans are less likely than whites to have evidence of moderate-severe steatosis (OR = 0.1), inflammation (OR = 0.2), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (OR = 0.2) upon histopathologic analysis.20

Racial Variations in Disease Presentation

Though African Americans exhibited higher HCV prevalence than whites, a retrospective study of 355 patients with HCV suggested that African Americans had a slower histological progression to fibrosis compared to non-African Americans. Compared to whites, African Americans were more likely to be infected with genotype 1 virus (88% versus 67%), have lower baseline serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 80.0 ± 5.5 U/L versus 112.1 ± 6.2 U/L; P < 0.001), and lesser degree of piecemeal necrosis.21 A study of African American prison inmates with HCV showed similar findings of higher prevalence of genotype 1 (94% versus 67%), lower baseline serum ALT (79 U/L versus 106), higher likelihood of having normal baseline ALT (57% versus 46%), and lower piecemeal necrosis scores (1.41 versus 1.72) compared to their white counterparts.22 From these findings, one could speculate that there may be a lesser degree of immunological response to HCV infection among African Americans.

There is conflicting data whether Hispanics with HCV follow a more aggressive HCV disease course than their white counterparts. A single-center study from Los Angeles showed that Hispanics (n = 169) were more likely than non-Hispanic whites (n = 63) to have higher fibrosis stage at index biopsy, greater degree of hepatic necroinflammation, and more rapid progression to fibrosis.23 Another study suggests that Hispanics with HCV have higher serum aminotransferases, bilirubin, and lower albumin than whites at initial presentation.24 In contrast, a multicenter study within the Veterans Administration found that Hispanics (n = 123) did not exhibit any difference in fibrosis stage or progression rate than whites (n = 743).25

Unlike chronic HCV, African Americans with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) may experience greater disease severity than whites. Lim et al. showed in a single-center retrospective study of 51 patients with AIH showed that African Americans were more than twice as likely to initially present with cirrhosis (85%) compared to whites (38%).26 Average prothrombin time was also more prolonged among African Americans than whites (16.4 seconds versus 13.5 seconds). In a larger single-center study of 101 patients with AIH, African Americans were more likely than whites to initially present with liver failure (37.8% versus 9.3%, P = 0.001) and more likely to require referral for transplantation (24.3% versus 6.2%, P = 0.009).27 At initial presentation, African Americans were also younger, more likely to be symptomatic, have higher prothrombin time and bilirubin, lower albumin, and greater degree of fibrosis than whites. As in the study by Lim et al., there was also a marginally significant trend for greater prevalence of cirrhosis among African Americans with AIH compared to whites (56.7% versus 37.5%, P = 0.06). The main limitation of these studies is that they did not address the potential confounding effects of cultural and socioeconomic factors that may affect access to healthcare. Although duration of symptoms were not different among African American and white individuals with AIH, whites were more likely to be asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis (36% versus 16%, P = 0.035). Thus, the findings from the above studies could be partly explained by African Americans seeking healthcare at a later symptomatic stage of disease or receiving delayed evaluation and therefore exhibiting a greater prevalence of cirrhosis at presentation.

Racial Disparities in the Treatment of Liver Disease

Several studies have suggested African Americans and Hispanics with HCV may be less likely than whites to be referred for medical therapy. A chart review of more than 4,000 medical charts from 4 clinic sites in Philadelphia revealed that only 32% of African Americans and 40% of Hispanics who had tested positive for HCV had documented referral to a specialist for interferon and ribavirin therapy compared to 71% of whites who tested positive for HCV.28 Another study from Los Angeles showed that even though Hispanics were more likely to be eligible for treatment, they were less frequently initiated on therapy and more likely to prematurely end treatment.25 Disparities in rates of referral for HCV therapy are further compounded by racial differences in response rate to interferon-based therapy.

Racial variations in immunological recognition of HCV may partly contribute to the lower response rates to medical therapy that have been consistently described among African Americans compared to whites.29-31 In a prospective trial of 48 weeks of pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy for predominantly genotype 1 HCV (>90%), African Americans (n = 100) had a considerably lower rate of sustained virological response (SVR) than whites (n = 100) (19% versus 52%, P < 0.001).32 They were also less likely to achieve virological response at 12 weeks and at the end of treatment. Importantly, this study showed that the racial differences in treatment response were independent of genotype, demographic, and socioeconomic predictors. African American race remained an independent predictor of poor response even after accounting for frequency of dose reduction and early termination of peginterferon and ribavirin therapy.33 A retrospective study of 42 African Americans and 90 non-Hispanic whites with HCV of genotypes 2 and 3 undergoing peginterferon and ribavirin therapy similarly showed lower SVR among African Americans (57% versus 82%, P = 0.012).34 Thus, disparities in response to HCV therapy between African Americans and whites pervade all viral genotypes.

Though a biological basis for differences in response between African Americans and whites has not been clearly defined, there may be racial differences in hepatic iron stores, a predictor of response to HCV treatment. An analysis of NHANES III demonstrated that HCV-positive African Americans were 5.4 times more likely than HCV-positive non-African Americans to have elevated ferritin and transferrin saturation. Moreover, the association between HCV infection and elevated hepatic iron stores was markedly more pronounced in African Americans (odds ratio: 17.8; 95% CI: 5.1-63) than in other races/ethnicities.35 However, it is not clear whether the presence of elevated iron stores is a causative factor or a just a marker of poor response to therapy. Interestingly, a retrospective study of prison inmates who underwent directly observed interferon and ribavirin therapy for genotype 1 HCV showed no differences in SVR.36 This finding tentatively posits that racial differences in response to HCV therapy may not be completely biological and that differences in medical adherence may also play a contributory role. Unlike African Americans, Asians with HCV and who were treatment-naïve were more than twice as likely to achieve SVR following pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy even after adjustment for genotype, body weight, hepatic fibrosis, and adherence.37 Differences in response to interferon therapy between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites have not been observed.29 These dramatic variations in race-specific differences in response to HCV therapy suggest that there is a genetic influence on antiviral response.

In stark contrast to the findings in chronic HCV infection, African Americans have a substantially higher rate of response to interferon therapy for HBV than whites. The rate of response, defined as loss of the hepatitis B e antigen and HBV DNA within 1 year of treatment, was 83% (5 of 6) in African Americans compared to 27% (26 of 97) in whites. Furthermore, two-thirds of African Americans eventually became negative for the hepatitis B surface antigen versus only 25% of whites. These racial differences were not explained by other clinical predictors of response including baseline aminotransferase and HBV DNA levels.38

Potential racial disparities in medical therapy have also been observed for AIH. In one large retrospective study, African Americans were less likely than whites to be treated for AIH (78% versus 94%, P = 0.02) and underwent a shorter duration of therapy (36.6 versus 64.7 months).27 African Americans were also less likely than whites to achieve remission (76% versus 90%, P = 0.02) and experience a longer time to remission (3.1 versus 2.4 months). In another study, the dosage of prednisone required at 3 months following initiation of therapy was higher in African Americans than whites, despite similar rates of concomitant immunosuppression with azathioprine.26 The amount of steroids required to maintain AIH in remission during follow-up was also 3-fold higher in African Americans than whites. At 12 months follow-up, there was a nonsignificant trend for African Americans to more likely be on azathioprine (74%) compared to whites (48%). These racial differences may reflect poorer response to immunosuppression among African Americans or alternatively, inadequate tapering of steroids and differences in provider practices.

In addition to racial differences in medical therapy, there is emerging evidence of disparities in the use of important surgical and endoscopic procedures. A nationwide analysis of 63,696 patients admitted for cirrhosis and portal hypertension between 1998 and 2003 revealed that African Americans (OR, 0.37; 95% CI: 0.27-0.51) and Hispanics (OR, 0.69; 95% CI: 0.54-0.88) were less likely than whites to receive temporizing shunt procedures for ascites and variceal bleeding.39 These racial differences were persistent after adjustment for age, gender, type of health insurance, geographic region, comorbidity, clinical predictors, and hospital characteristics. Furthermore, African American variceal bleeders were more likely to have delayed endoscopic hemostasis (>24 hours after admission) compared to whites (OR, 1.7; 95% CI: 1.2-2.4).

Complications of Chronic Liver Disease: Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a long-term sequela of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis with an increasing number of new cases in the United States.40, 41 For unclear reasons, the incidence of HCC in African Americans is more than twice that of whites (incidence rate ratio, 2.66; 95% CI: 2.51-2.83).40 There has been speculation that these racial differences may arise from the 2-fold higher nationwide prevalence of HCV among African Americans compared to whites, whereas for Asians, HBV infection appears to be the dominant predisposing factor.42 A recent study has shown that Hispanics exhibited a 2.7-fold higher incidence of HCC compared to non-Hispanic whites.43 Importantly, between 1992 and 2002, there was a 63% and 31% increase in HCC among Hispanic women and men, respectively. There were racial differences in the risk of developing HCC even within the subgroup of patients with liver disease with HCV. A matched case-control study found that African Americans were nearly 2-fold as likely as whites to progress to HCC, while Asians had a 4-fold risk.44 Increased frequency of HBV coinfection and concomitant diabetes mellitus among African Americans may also contribute to higher rates of HCC in this minority group.45 Moreover, an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry suggests that African Americans present with HCC at an earlier age, were more likely to have regional and distant metastases and less likely to have resective surgery compared to whites.46

If not treated in its early stages, survival after HCC diagnosis is dismal. Furthermore, age-adjusted death rates from HCC between 1991 and 1995 were considerably higher in African Americans than whites, and the mortality difference was most pronounced between African American and white men (6.0 versus 3.4 per 100,000).41 In a subsequent analysis of the SEER registry, African Americans and Hispanics had an 11% and 9%, respectively, higher relative mortality rate compared to whites.47 In contrast, Asians had a 16% relatively lower rate of mortality than whites. Interestingly, African Americans who were appropriate candidates for therapy had lower likelihood of undergoing either local ablation or surgery for HCC compared to whites (44% versus 53%) while Asians had higher rates of local and surgical therapy (64% versus 53%). The racial difference in mortality risk between whites and African Americans was eliminated after adjustment for receipt of therapy, disease stage, and other demographic factors, while racial differences among Asians, Hispanics, and whites persisted. Thus, socioeconomic factors such as access to interventional therapy for HCC may contribute to racial differences in survival at least for certain minority subgroups.

Racial Disparities in Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation is a life-saving procedure therapy of choice for patients with end-stage liver disease and its dreaded complications, including HCC. Several studies have raised concern over racial disparities in the utilization of liver transplantation. A single-center study suggests that African Americans were disproportionately underrepresented among patients referred for liver transplant evaluation (14.1%) relative to the prevalence of end-stage liver disease in the African American population.48 Those African Americans who were referred were evaluated at a later stage in their disease course and were more critically ill compared to whites. However, acceptance rates for listing for transplantation and proportion of patients referred that actually underwent transplantation were similar for both races.

These findings were substantiated by a nationally representative analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database which showed that African Americans were underrepresented on the transplant waiting list (8.4%) and among recipients of transplantation (7.9%) relative to the general population, where they comprise 13.6% of the total census.49 More importantly, African Americans were more likely to die or to become too ill before transplantation within 4 years of listing compared to whites (OR, 1.5; 95% CI: 1.2-2.0). Among those referred for transplantation, African Americans were also less likely to receive transplantation within 4 years of listing (OR, 0.7; 95% CI: 0.5-0.9). Because the UNOS database contains only patients who have overcome healthcare and social barriers to make it on the transplant waiting list, the study's findings likely underestimate racial disparities in utilization of liver transplantation.

A subsequent nationwide analysis of patients hospitalized for decompensated cirrhosis found even larger disparities in liver transplantation.39 Compared to white patients hospitalized for cirrhosis and portal hypertension, African Americans (OR, 0.32; 95% CI: 0.20-0.52) and Hispanics (OR, 0.46; 95% CI: 0.25-0.83) were considerably less likely to receive liver transplantation. These results were adjusted for demographic, clinical, and hospital factors as well neighborhood income, an index of socioeconomic status.

A common limitation of the above studies is that they did not account for disease severity using the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) system, a validated and widely accepted predictor of mortality specific for liver disease. Disparities in liver transplant rates that are independent of disease severity or necessity are likely due to cultural and social factors such as patient preferences, healthcare access, and availability of social support.

Race/Ethnicity and Post–Liver Transplant Outcomes

There is emerging evidence that African Americans who do undergo liver transplantation have worse posttransplant outcomes than their white counterparts. A cohort study of UNOS liver transplant recipients showed that 2-year graft survival was significantly lower in African Americans (68%) and Asians (64%) than in whites (74%) and Hispanics (72%).50 Consequently, both 2-year and 5-year survival rates were lower in African Americans (74% and 48%) and Asians (69% and 37%) compared to that of whites (83% and 58%) and Hispanics (79% and 52%). A subsequent study of UNOS data demonstrated that socioeconomic parameters such as neighborhood income did not contribute to the observed disparities, while education had a marginal influence. Being a Medicare or Medicaid recipient was associated with lower survival compared to private insurance. After adjustment for socioeconomic status, African Americans had persistently higher 5-year risk of graft failure (hazard ratio, 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1-1.5) and death (hazard ratio, 1.4; 95% CI: 1.2-1.6).51 Although the mechanisms for these disparities are unclear, increased recurrence of HCV and poorer response to interferon-based therapy may play a role.52 In addition, African Americans are more likely than whites to have posttransplant diabetes mellitus, which has been shown to be a predictor of posttransplant complications.53, 54 Among HCV patients, the prevalence of pretransplant diabetes mellitus in African Americans is more than twice that of whites and predisposes to worse 5-year posttransplant survival.55 Despite differences in graft and patient survival, a single-center study did not find differences in health-related quality of life or functional performance between African Americans and whites.56

Racial Disparities in Liver Cirrhosis Mortality

The sum of effects arising from racial disparities in chronic disease prevalence, presentation, treatment, complications, and utilization of liver transplantation is a consistent pattern of differences in disease-specific mortality associated with liver cirrhosis.2, 3 In AIH, overall mortality was estimated to be 4-fold higher in African Americans than whites (24.3% versus 6.2%, P = 0.009). The risks for a poor outcome defined as liver failure at presentation, failure to achieve remission, need for liver transplantation, or death was 2-fold higher in African Americans compared to whites27 based on data from the National Vital Statistics System among all patients with cirrhosis between 1968 and 1997. Both African Americans (hazard ratio, 1.9; 95% CI: 1.4-2.6) and Hispanics (hazard ratio, 2.0; 95% CI: 1.3-2.9) had an almost 2-fold risk of death from liver cirrhosis compared to whites.3 At its peak in 1973, the mortality rate was 35.3 per 100,000 for African American men, 19.2 per 100,000 for white men, 18.4 per 100,000 for African American women, and 8.7 per 100,000 for white women.2 For African Americans, these racial mortality differences were dissipated after additional adjustment for education, occupation, and family income. Paradoxically, after adjustment for socioeconomic factors, the mortality gap between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites became even more disparate (hazard ratio, 2.4; 95% CI: 1.5-4.0). These findings underscore the paramount contribution of socioeconomic factors to racial disparities in liver disease-related outcomes.

Interpretation of Racial Disparities Studies in Liver Disease

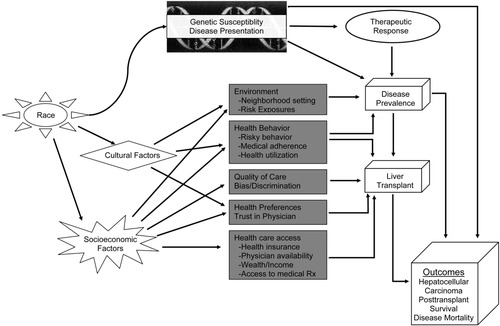

We have provided evidence that the burden of chronic liver disease, particularly HCV infection, is greater among certain racial and ethnic minorities. There is further data suggesting treatments for chronic liver disease, especially life-saving liver transplantation, is underutilized among African Americans and Hispanics. The primary goal of these studies in health disparities is to understand their underlying mechanisms and to ultimately implement strategies to rectify them. In fact, race is intricately interwoven with socioeconomic, cultural, and biological predictors of health outcomes, and may be a surrogate marker for these other parameters. Therefore, racial disparities may reflect differences in social class, healthcare access, and quality of care (Fig. 1). Any conclusions from racial disparities studies can only be meaningful when these other factors are taken into consideration.57

A diagrammatic schema depicts the complex and interwoven biological, cultural, and socioeconomic mediators of racial disparities in disease prevalence, liver transplantation, and liver disease outcomes, including hepatocellular carcinoma, posttransplant survival, and mortality.

The leading causes of chronic liver disease (HCV and alcoholic liver disease) are largely preventable and disproportionately affect certain minority groups through socioeconomic and cultural factors as well as biological vulnerability. Mortality outcomes, which are the final endpoint of chronic liver diseases, are also strongly influenced by socioeconomic factors. Racial disparities in mortality between African Americans and whites are dissipated after adjustment for socioeconomic status. In contrast, the mortality gap between Hispanics and whites appear to be persistent if not strengthened by accounting for socioeconomic status. Social and cultural contributions to racial disparities in the healthcare process, including use of liver transplantation and medical treatment of liver disease, are more nebulous and poorly characterized in the current literature. Based on data from the renal transplantation literature, disease severity and comorbidity,58 low referral rates,59 patient preferences,60 and socioeconomic factors61, 62 may all contribute to disparities in solid-organ transplantation. Studies in liver transplantation have yet to address the potential role of social class and racial differences in patient preferences in observed lower rates of transplants among African Americans and Hispanics. Disease severity in chronic liver disease presumably has a prominent biological basis, but all of the studies that have explored racial disparities in disease presentation have been retrospective. Prospective studies are necessary to validate the current findings and to exclude confounding factors from socioeconomic factors such as healthcare access and education that can influence at what stage of liver disease an individual decides to seek medical care. Other aspects of the healthcare process such as race-specific and ethnicity-specific response to interferon therapy are likely to be predominantly biological, based on efficacy studies in clinical trials. However, their effectiveness in the general population must take into consideration potential racial differences in nonadherence that can further amplify disparities in response.

Most of the disparities studies discussed here are descriptive and exploratory and do not allow a clear delineation between biological, social, or cultural mechanisms. These studies, however, serve an important role in highlighting important issues in liver disease for an increasingly diverse U.S. society. The next critical step is the design of prospective racial disparities studies that will deliberately take into consideration the contributions of socioeconomic status (education, income, wealth, occupational prestige), health preferences, healthcare access, quality of care, and physician trust. Disparities that remain after effective adjustment for the above factors are then possibly mediated by a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, culturally and individually driven health behavior, and racism and discrimination. Only through an understanding of how race and ethnicity influence health outcomes can policies and interventions be devised to reduce racial gaps in the burden of liver disease.