The impact of ethnicity on the natural history of autoimmune hepatitis†

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

The impact of ethnicity on the natural history of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) has not been well characterized. The aim of this study was to assess the natural history of AIH in blacks in comparison with others (nonblacks). This was a 10-year (June 1996 to June 2006) retrospective analysis of patients with AIH from a single tertiary care center. The diagnosis of AIH was defined by the criteria established by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Club. A poor outcome was defined as liver failure at presentation, failure to achieve remission, need for liver transplantation, and/or death. One hundred one patients with AIH were eligible for the study. Black patients were more likely to have cirrhosis (56.7% versus 37.5%, P = 0.061), have liver failure at the initial presentation (37.8% versus 9.3%, P = 0.001), and be referred for liver transplantation (51.3% versus 23.4%, P = 0.004). The overall mortality was also significantly higher in black patients (24.3% versus 6.2%, P = 0.009). Compared with nonblacks, blacks had more advanced hepatic fibrosis (3.6 ± 2.7 versus 2.1 ± 2.4, P = 0.013). A Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the probability of developing a poor outcome was significantly higher in blacks (P = 0.003). Independent predictors of poor outcome were black ethnicity, the presence of cirrhosis, and the fibrosis stage at presentation. Black males were the group most likely to have a poor outcome (85.7%). Conclusion: Blacks, especially black men with AIH, have more aggressive disease at the initial presentation, are less likely to respond to conventional immunosuppression, and have a worse outcome than nonblacks. (HEPATOLOGY 2007.)

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic disorder of unknown etiology characterized by unresolving hepatic inflammation, a female preponderance, the presence of autoantibodies, and chronic hepatitis that typically shows prominent plasma cells and active lobular inflammation.1 Approximately 80% of patients achieve remission by a combination of steroids and azathioprine, and these and similar drugs have significantly improved long-term survival in such patients.2, 3 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines define remission as aminotransferases less than 2 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) along with an absence of symptoms.1 Recent studies, however, indicate that the achievement of normal aminotransferases [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)] may be a better goal for optimal patient management.4, 5 About 20%–40% of patients with AIH have cirrhosis at the initial presentation, and despite therapy, a similar proportion develops cirrhosis during follow-up.4, 6 It is not known whether the presence of cirrhosis at either presentation or follow-up is associated with a worse outcome.4, 6, 7

A number of other factors have also been associated with poor outcome in those with AIH. A failure to achieve normal aminotransferases during therapy has been shown to be associated with an increased propensity to relapse, the development of cirrhosis (and its complications), and therefore increased mortality.4, 5, 8 Similarly, the histological presence and localization of plasma cells (especially in the portal area) may predict a higher risk for relapse.4, 9 There are data to suggest that genetic factors and therefore ethnicity may also influence the natural history of AIH. Type 1 AIH is associated with human leukocyte antigen DR3 (DRB1*0301) and human leukocyte antigen DR4 (DRB1*0401) in white North European and North American patients.10, 11 It has been suggested that white patients with type 1 AIH and DRB1*0301 are more likely to have treatment failures and require liver transplantation.12, 13 In contrast, patients with DRB1*0401 are older and respond better to steroids.12, 14 The data on the natural history of AIH, however, are derived from studies of white or Japanese patients,15 and there is a paucity of data on other ethnic groups. A small study of 12 nonwhite patients with AIH [6 African American (AA), 5 Asian, and 1 Arabic] reported that as a group they were younger, were more likely to present with cholestatic biochemistry, and showed a poorer initial response to standard therapy.15 Our anecdotal experience suggests that black patients with AIH have more aggressive disease at presentation. To further address this important clinical question, we conducted this study to objectively analyze the natural history of AIH in blacks versus nonblacks, with a special emphasis on the severity of disease at the initial presentation, the liver histology, and the predictors of outcome.

Abbreviations

AA, African American; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ANA, antinuclear antibody; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DRB1*0301, human leukocyte antigen DR3; DRB1*0401, human leukocyte antigen DR4; INR, international normalized ratio; LKM, liver kidney microsomal; SD, standard deviation; SMA, smooth muscle antibody; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Patients and Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed of all adult patients (18 years of age or older) with AIH who were evaluated at our institution between June 1996 and June 2006. Patients were identified from 2 sources: the pathology database, and secondly the list of patients with a primary diagnosis of AIH currently waiting for liver transplantation at our institute (as of June 2006). A detailed review of the medical records was then performed with our electronic patient record system. Those who initially presented in the pediatric age group but then were transferred to adult hepatologists were also included. AIH was defined by criteria established by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Club.16 The exclusion criteria included incomplete medical records, the presence of an overlapping syndrome, the presence of a coexistent disease (for example, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, biliary pathology, viral hepatitis, and alcohol-induced liver injury), and unclear diagnoses. Other causes of liver disease were excluded by appropriate biochemical tests and imaging. The definitions that were used in the study are shown in Table 1.

| Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute presentation | Bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/dL and/or AST/ALT > 1000 IU/L |

| Remission | Resolution of clinical symptoms and AST/ALT < 2 × ULN |

| Relapse | Presence of any degree of hepatic encephalopathy and/or INR ≥ 2 |

| Noncompliance | Self-discontinuation of therapy by the patient without prior consultation with the treating hepatologist |

| Poor outcome (any of the following) | Presence of liver failure at presentation |

| Failure to achieve remission | |

| Need for a liver transplant | |

| Liver-related mortality |

All liver biopsies were reviewed by a single experienced liver pathologist (M.T.) without knowledge of the patients' clinical or biochemical data. Inflammation and fibrosis were graded and staged, respectively, with the modified histological activity index scoring system.17 In addition, we assessed (graded) the presence of portal and parenchymal plasma cells and eosinophils (semiquantitatively) as follows: 0 (no more than occasional plasma cells/eosinophils), 1 (mildly prominent), 2 (more than mildly prominent to nearly as common as lymphocytes), and 3 (more common than lymphocytes). Cholestasis was subdivided into lobular, ductular, and bile ductular reactions. Each was graded as 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (marked). For the data analysis, we reported cholestasis to be present (≥grade 1) or absent (grade 0)

Statistics.

The data are presented as the means ± the standard deviation (SD). Differences between continuous variables were analyzed with a Mann-Whitney test, and differences between categorical variables were analyzed by a chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. A 2-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. To assess independent predictors of poor outcome, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed. A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to assess the outcomes in blacks versus nonblacks and to assess the impact of cirrhosis on the outcomes. The differences between groups were analyzed with a log-rank test. The statistical software that was used was SPSS version 14.

Results

One hundred and fifty-seven patients were identified, 11 of whom had biopsies reviewed but were never seen at our institution. Of the remaining 146, we excluded 45 patients for the following reasons: 7 had overlapping syndromes, 15 had incomplete medical records, 1 was not followed up by an adult hepatologist, and 22 had alternative diagnoses (4, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; 3, hepatitis of unclear etiology; 3, nonspecific histology; 5, viral hepatitis; 4, drug-induced liver injury; and 3, cryptogenic cirrhosis). The remaining 101 patients fulfilled the criteria for AIH as established by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Club and were therefore found to be eligible for the study. Of these 101 patients, 98 were identified from the pathology database, and 3 were currently listed for liver transplantation with a primary diagnosis of AIH. Sixty-eight (67%) had definite AIH, and 33 (33%) had probable AIH. One of these patients was antimitochondrial antibody–positive, although clinically, biochemically, and histologically she had no features to suggest primary biliary cirrhosis. Moreover, this patient had a pretreatment AIH score of 19, and she achieved complete remission with immunosuppressants. She was therefore not considered to have an overlapping syndrome and was included in the study. Because liver kidney microsomal (LKM) antibodies are rare in the United States (seen in only about 4% of adults with AIH),18 they are not routinely measured at our center. Only 3 patients were tested for LKM antibodies, 1 of whom was positive: a 36-year-old female negative for both antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and smooth muscle antibodies (SMAs). Three patients presented in the pediatric age group, 2 of whom had ANA and/or SMA > 1:80. None of the patients had a history of ongoing alcohol excess, although 2 had abused alcohol in the past. Neither of these 2 patients had any histological evidence of alcohol-induced liver injury. All but 1 patient had undergone a liver biopsy (this patient presented with decompensated cirrhosis). Liver biopsies at the initial presentation were not available for review in another 17 patients for the following reasons: 9 biopsies were performed at outside hospitals (5 of these were reviewed by pathologists at Johns Hopkins Hospital at the initial presentation, and slides were sent back), 1 biopsy attempt failed, 2 biopsies provided inadequate tissue for staging/grading (both biopsies were reviewed at the initial presentation), and 5 biopsies were performed at our institution but were not available for review (all 5 were previously read by pathologists at Johns Hopkins Hospital).

Table 2 shows the demographic data of the entire cohort at entry. Of the 64 nonblacks, there were 56 whites and 8 nonwhite nonblacks (predominantly Asians and Hispanics). Of the 37 blacks, 34 were of AA descent, and 3 were non-AA blacks. Cirrhosis was present in 44.6% of the patients (Table 1). Of these, 37 (36.6%) had cirrhosis at the initial presentation, and 8 (7.9%) developed it during follow-up (for 6 this was confirmed histologically, and 2 developed clinical and radiological features of cirrhosis). The mean time to cirrhosis development in 6 of the 8 patients was 82 ± 27.8 months. The time to cirrhosis development was not available in 2 patients. Those 2 patients had a long history of AIH (>30 years) at their first presentation to our institute. Data on autoantibodies were not available for 9, and of the remaining 92 patients, 83 (90.2%) had ANA and/or SMA > 1:80. Twelve patients were not treated with immunosuppressants (Table 1); of these, 7 were referred on presentation for liver transplantation (6 of these had liver failure), 1 achieved spontaneous remission, 1 had burnt-out AIH, and 3 had aminotransferases less than 2 times ULN at presentation.

| Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44 ± 17 |

| Female | 78 (77.2%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Black | 37 (36.6%) |

| Nonblack | 64 (63.3%) |

| Cirrhosis | 45 (44.6%) |

| Presented acutely | 60 (59.4%) |

| Treated | 89 (88.1%) |

| Achieved remission | 76/89 (85.3%) |

| Initial biopsy available for review | 83 (82.1%) |

| Total follow-up (months) | 46.1 ± 38.3 (38.6–57.7) |

- The data are presented as the means ± the SD.

Table 3 shows data for blacks and nonblacks. The blacks were younger and more likely to be symptomatic, present acutely, and have more severe disease at the initial presentation. The international normalized ratio (INR) was significantly higher and the serum albumin (g/dL) was lower at presentation in the blacks (Table 3). The blacks also tended to have higher bilirubin and aminotransferases (IU/L) at presentation, although the results did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). Twenty-one (56.7%) blacks and 24 (37.5%) nonblacks had cirrhosis (P = 0.061). Overall, the blacks were less likely to achieve remission and more likely to be referred for a liver transplant. The overall mortality was also significantly higher in the blacks (24.3% versus 6.2%; Table 3).

| Parameter | Blacks (n = 37) | Nonblacks (n = 64) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.5 ± 17.9 | 44.7 ± 16.6 | 0.58 |

| Female | 30 (81%) | 48 (75%) | 0.48 |

| Weight (lbs) | 170 ± 51.4 | 171.1 ± 37 | 0.56 |

| Symptoms | 31 (83.7%) | 41 (64%) | 0.035 |

| Jaundice | 24 (64.8%) | 31 (48.4%) | 0.11 |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 2.6 ± 4.5 | 2.3 ± 3.0 | 0.51 |

| Acute presentation | 28 (75.6%) | 32 (50%) | 0.011 |

| Presence of other autoimmune diseases | 11(29.7%) | 29 (45.3%) | 0.12 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 12.4 ± 10.0 | 10.3 ± 10.7 | 0.21 |

| AST (IU/L) | 981.9 ± 717.7 | 803.2 ± 640.3 | 0.20 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 190.7 ± 87.6 | 190.9 ± 88.4 | 0.22 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 4.02 ± 1.0 | 0.67 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.007 |

| INR | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.002 |

| Cirrhosis | 21 (56.7%) | 24 (37.5%) | 0.061 |

| Developed cirrhosis complications | 9 (24.3%) | 11 (17.1%) | 0.10 |

| Treated | 29 (78.3%) | 60 (93.7%) | 0.021 |

| Duration of therapy (months) | 36.6 ± 35.6 | 64.7 ± 78.9 | 0.047 |

| Liver failure at presentation | 14 (37.8%) | 6 (9.3%) | 0.001 |

| Remission | 22/29 (75.8%) | 54/60 (90%) | 0.016 |

| Time to remission (months) | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 0.028 |

| Referred/listed for liver transplantation | 19 (51.3%) | 15 (23.4%) | 0.004 |

| Transplanted | 8/19 (42.1%) | 5/15 (30%) | 0.014 |

| Death | 9 (24.3%) | 4 (6.2%) | 0.009 |

| Poor outcome | 21 (56.7%) | 15 (23.4%) | 0.001 |

| Total follow-up (months) | 42.9 ± 40.5 | 48.0 ± 38.2 | 0.300 |

- The data are presented as the means ± the SD. The normal ranges for the liver panel are as follows: bilirubin, 0.1–1.2 mg/dL; AST, 0–37 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 30–120 U/L; albumin, 3.5–5.3 g/dL; and globulin, 2.5–2.9 g/dL.

Of the 89 patients who received immunosuppression, 20 blacks (68.9%) and 47 nonblacks (78.3%) were initially treated with steroids (prednisone, methylprednisone, and hydrocortisone) only (P = 0.046). The initial mean steroid dose (mg) was higher in the blacks, although the difference did not reach statistical significance [(57.5 ± 20.2 (25.3–89.6) versus 40.6 ± 12.5 (35.3–45.9), P = 0.37]. Of the 89 patients who were treated, in 32 (35.9%; 12 blacks and 20 nonblacks), the drugs were discontinued after a mean period of 29.6 ± 30 (18.9–40.2) months; all 32 relapsed. Overall, the drugs were discontinued in 12 of 30 (40%) blacks and 20 of 60 (33.3%) nonblacks. In 10 patients, the drugs were discontinued by the physician; in 11, the drugs were discontinued by the patients; and in 11, the relapse occurred during an attempted dose reduction of the immunosuppressants. Of the 11 patients who self-discontinued therapy, 6 (54.5%) were blacks. All 11 were recommenced on therapy, and all but 2 (both black) reachieved remission (1 developed decompensated cirrhosis during follow-up, and the second developed liver failure during the relapse; both died). Neither of these 2 black patients had cirrhosis at the initial presentation. When the 2 noncompliant black patients who died were excluded from the analysis, the prevalence of a poor outcome remained higher in the blacks [(19/37 (51.3%) versus 15/64 (23.4%), P = 0.004)].

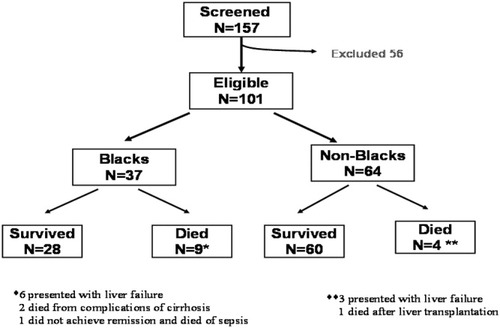

Of the 9 deaths in blacks (Table 3), 6 occurred in those with an initial presentation of liver failure (2 underwent liver transplantation but died after transplantation, 1 developed fungal sepsis and was not evaluated for transplantation, and 3 were being evaluated/listed for liver transplantation but died from liver failure). Two more died from cirrhosis complications (in 1, there was suspected noncompliance, although both had been evaluated/listed for transplantation), and 1 failed to achieve remission and died from Klebsiella sepsis. In the nonblacks, 3 deaths occurred in those with liver failure at presentation (all 3 were being evaluated for liver transplantation), and 1 death occurred for a patient with decompensated cirrhosis who died after liver transplantation. Figure 1 summarizes the study design and outcomes of the whole cohort.

Study design and outcomes in the whole cohort.

Table 4 shows the histology data for the 2 groups. Biopsies were available for 28 (76%) blacks and 55 (86%) nonblacks (P = 0.19). There were no significant differences in the inflammatory parameters, including plasma cells. Blacks, however, had a significantly higher fibrosis stage at presentation (Table 4).

| Histological finding | Blacks (n = 28) | Nonblacks (n = 55) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation (grade) | |||

| Portal | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.89 |

| Interface | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 0.67 |

| Lobular | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 0.43 |

| Necrosis | 1.3 ± 2.2 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 0.86 |

| Portal plasma cells | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 0.48 |

| Lobular plasma cells | 0.44 ± 0.7 | 0.42 ± 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Portal eosinophils | 0.37 ± 0.7 | 0.42 ± 0.5 | 0.41 |

| Lobular eosinophils | 0.19 ± 0.3 | 0.11 ± 0.3 | 0.58 |

| Fibrosis stage | 3.6 ± 2.7 | 2.1 ± 2.4 | 0.013 |

| Cholestasis | 12 (42.8%) | 21 (38.1%) | 0.23 |

| Number of portal tracts | 15.5 ± 6.1 | 15.6 ± 5.6 | 0.81 |

- The data are presented as the means ± the SD.

An analysis of the data by the stratification of individuals into those with and without a poor outcome (Table 5) shows that those with worse outcomes were younger and were more likely to be black, to have jaundice, coagulopathy, and cirrhosis at presentation, and to take a longer time to achieve remission. Noncompliance was higher in those with a poor outcome (Table 5). However, only 2 noncompliant patients (both blacks) did not reachieve remission, and hence for them the poor outcome was a direct result of the noncompliance. For the remaining 4 noncompliant patients, the poor outcome was not related to the noncompliance, as 2 presented with liver failure (both black) and 2 had cirrhosis at presentation (1 black and 1 nonblack), both developing decompensated disease during follow-up and requiring referral for liver transplantation. In the latter 2 patients, it was unlikely that the single episode of transient noncompliance contributed to the decompensation. Those with a poor outcome had a trend toward higher portal and lobular plasma cell scores, but these differences were not statistically significant (Table 5). The portal eosinophil cell score, however, was significantly lower in the group with a poor outcome (Table 5). Variables that were significant for predicting the outcome (P ≤ 0.05; Table 5) were then entered into a binary logistic regression analysis model. The following variables were entered into the model: ethnicity (blacks versus nonblacks), presence of jaundice, symptoms, acute presentation, presence of cirrhosis, cholestasis, age, bilirubin, albumin, INR, time to remission, portal eosinophil score, and fibrosis stage. Variables independently associated with a poor outcome were (Table 6) black ethnicity, the presence of cirrhosis, and the fibrosis stage at presentation.

| Parameter | Poor outcome (n = 36) | No poor outcome (n = 65) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.2 ± 17.2 | 46.6 ± 16.2 | 0.042 |

| Female | 28 (77.7%) | 50 (76.9%) | 0.92 |

| Black | 21 (58.3%) | 16 (24.6%) | 0.001 |

| Presence of symptoms | 32 (88.8%) | 40 (61.5%) | 0.004 |

| Jaundice | 26 (72.2%) | 29 (44.6%) | 0.008 |

| Acute presentation | 26 (72.2%) | 34 (52.3%) | 0.051 |

| Cirrhosis | 23 (63.8%) | 22 (33.8%) | 0.004 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 15.3 ± 10.4 | 8.8 ± 9.7 | 0.002 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 755.6 ± 609.7 | 790.1 ± 670.3 | 0.89 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 0.093 |

| INR | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| Treated | 29 (80.5%) | 60 (92.3%) | 0.080 |

| Duration of therapy (months) | 53.2 ± 105 | 57.0 ± 43.0 | 0.64 |

| Noncompliance | 6/29 (20.6%)* | 5/60 (8.3%) | 0.058 |

| Time to remission (months) | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 0.04 |

| Other autoimmune disorders | 14 (38.8%) | 26 (40%) | 0.91 |

| Histology | |||

| Inflammation (grade) | |||

| Portal | 2.08 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.34 |

| Interface | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 0.78 |

| Lobular | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 0.72 |

| Necrosis | 1.5 ± 2.3 | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 0.49 |

| Portal plasma cells | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 0.29 |

| Lobular plasma cells | 0.54 ± 0.6 | 0.38 ± 0.7 | 0.12 |

| Portal eosinophils | 0.17 ± 0.4 | 0.50 ± 0.6 | 0.015 |

| Lobular eosinophils | 0.04 ± 0.2 | 0.17 ± 0.4 | 0.15 |

| Fibrosis stage | 4.0 ± 2.6 | 2.05 ± 2.4 | 0.002 |

| Cholestasis | 13/25 (52%) | 20/58 (34.4%) | 0.016 |

| Total follow-up (months) | 36.9 ± 40.3 | 51.2 ± 36.5 | 0.012 |

- The data are presented as the means ± the SD (95% confidence interval).

- * In only 2 of 6 noncompliant patients, the poor outcome was a direct result of the noncompliance

| Predictor | Standard Error | Wald Test | Degrees of Freedom | P | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 0.55 | 4.5 | 1 | 0.034 | 3.2 | 1.1–9.3 |

| Blacks | 0.51 | 5.0 | 1 | 0.025 | 3.1 | 1.1–8.5 |

| Fibrosis stage | 0.62 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.052 | 3.3 | 0.98–11.1 |

Of the 7 black males, 6 of 7 (85.7%) had a poor outcome versus 15 of 30 (50%) black females (P = 0.002). In contrast, nonblack females (13/48, 27%) were more likely to have a poorer outcome in comparison with nonblack males (2/16, 12.5%, P = 0.001). Our cohort included only 8 nonblack, nonwhite subjects, and therefore a detailed analysis of this group was not performed. Overall, the blacks had the worst outcome (21/37, 56.7%), followed by nonblack nonwhites (3/8, 37.5%) and whites (12/56, 21.4%). The differences between these groups were significant (blacks versus nonblack nonwhites, P = 0.002; blacks versus nonblacks, P = 0.001; whites versus nonblack nonwhites, P = 0.002).

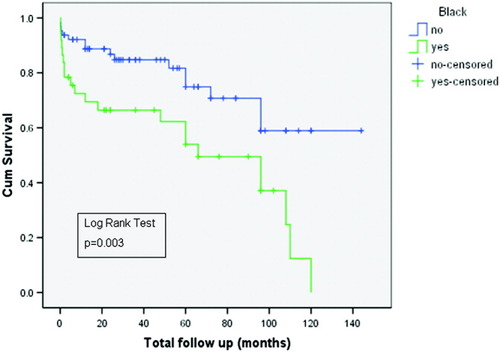

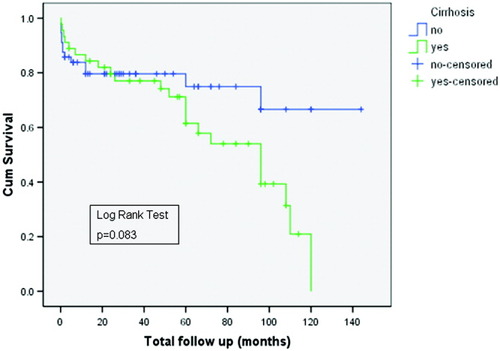

The probability of having a poor outcome over the follow-up period among blacks and nonblacks is shown in Fig. 2. After a follow-up of 60 months, approximately 50% of the blacks had experienced 1 or more adverse events versus approximately 25% of the nonblacks (P = 0.003). We did not perform a time-dependent analysis of the poor outcomes for 2 reasons. First, most of the adverse events (67.5%) occurred at the initial presentation. Second, the number of patients with a poor outcome (n = 36) was small, and this limited the interpretation if they were analyzed separately. The impact of cirrhosis on the outcome is shown in Fig. 3. Although the differences were not significant (P = 0.08), there was a trend toward a worse outcome in those with cirrhosis.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the probability of developing a poor outcome in blacks versus nonblacks with AIH.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the probability of a poor outcome depending on the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the impact of ethnicity on the natural history of AIH. The black patients (of whom 89% were AA) with AIH had more aggressive disease clinically, biochemically, and histologically in comparison with the nonblacks. At the initial presentation, they were 2 and 4 times as likely to have cirrhosis (56.7% versus 27.5%) and liver failure (37.8% versus 9.3%), respectively. They were also less likely to achieve remission (75.8% versus 90%). This resulted in an increased referral rate for liver transplantation (51.3% versus 23.4%) and a 4-fold increased mortality (24.3% versus 6.2%) in blacks. This was especially true for black males where all but 1 (85.7%) had a poor outcome. Independent predictors of a poor outcome were black ethnicity, the presence of cirrhosis, and the fibrosis stage at presentation. Although LKM antibodies were not routinely tested in our patients, because of the very low prevalence of type 2 AIH in such a cohort, our data are representative of those with type 1 AIH.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital is a tertiary referral center; therefore, our AIH cohort may be sicker than that reported in other studies. This selection bias, however, would have affected both blacks and nonblacks equally, and thus would be an unlikely explanation for the poorer outcomes in blacks. It is possible that economic disparity and thus access to health care may have played a role, but our data do not support this assumption. First, the duration of symptoms was no different in the 2 groups, and this indicated that blacks were not seeking medical attention later than their nonblack counterparts. However, nonblacks were more likely to have their disease diagnosed in the presymptomatic phase than blacks (23/64, 35.9%, versus 6/37, 16.2%, P = 0.035). Only 4 patients who were asymptomatic at diagnosis (3 nonblacks and 1 black) eventually had a poor outcome, and thus this factor was unlikely to have influenced our results. Second, of the 19 blacks referred for a liver transplant, 8 (42.1%) were eventually transplanted (of whom 6 presented with liver failure). In contrast, 15 nonblacks were evaluated for a liver transplant, of whom 5 (30%) were eventually transplanted (none presented with liver failure) (P = 0.014). Therefore, it does not appear that failure of access to liver transplantation contributed to the higher mortality in the blacks. Finally, the blacks were younger at presentation, and this indicated that they had more aggressive disease rather than delayed medical care.

Noncompliance was higher in blacks (20.6% versus 8.3%, P = 0.019), and this could partly explain our results. Only 2 of the noncompliant black patients, however, had a poor outcome directly related to the noncompliance (failure to reachieve remission), and even if those 2 were excluded from the analysis, a poor outcome was still more likely in blacks (51.3% versus 23.4%, P = 0.004).

Could then these differences be related to genetic variations in the metabolism of immunosuppressive agents15 and/or increased resistance to standard doses of immunosuppressants in blacks?19 Nonwhite liver allograft recipients have in fact been shown to have poorer graft survival than white recipients, with more than a 2-fold higher incidence of chronic graft rejection (12.6% versus 5.9%).20 Black renal transplant recipients require an approximately one-third higher mean dose of tacrolimus to achieve and maintain equivalent blood concentrations in comparison with whites,21 and a significant reduction in the bioavailability of tacrolimus in blacks versus nonblacks has been demonstrated.22 This may explain the higher rates of chronic rejection and graft loss in black renal transplant recipients.23 A higher requirement for methylprednisolone in the transplant setting has also been reported for blacks,19 although data on azathioprine metabolism in different races are conflicting.24, 25 There is some evidence to suggest that these data are relevant to those with AIH. Lim et al.26 observed that although the initial dose of steroids at 1 year was not different among blacks and whites, during the follow-up period, higher doses of steroids were required for blacks (mean 18.2 versus 6.1 mg). Zolfino et al.15 also reported a poorer initial response to medical therapy in 12 nonwhite patients with AIH. In our study, the mean initial dose of steroids was higher in the blacks (57.5 versus 40.6 mg). This was perhaps related to resistance to immunosuppressants or due to more aggressive disease (which was, therefore, more difficult to treat) at onset; a retrospective study of this nature will not be able to address this question. Earlier studies have in fact shown that patients with AIH who have cirrhosis have more difficult to treat disease, needing more prolonged therapy to achieve remission with a higher risk of relapse.4, 27

Previous studies have shown significant differences in the natural history of other autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and type 1 diabetes mellitus among blacks and other racial groups.28, 29 Thus, it is conceivable that there may be genetic differences in the natural history of AIH between blacks and nonblacks. We did not have any data on human leukocyte antigen class 11 genotypes for our patients, and this certainly needs to be addressed in future studies.

Other investigators have also observed ethnic differences in the outcome of AIH. A small study reported increased liver transplantation and/or death in 12 nonwhite subjects (of whom 5 were AA) in comparison with their white counterparts (33.3% versus 11.7%).15 Another study observed that blacks with AIH were more likely to present with cirrhosis (85% versus 38%) and have a higher mean prothrombin time than whites (16.4 versus 13.5).26 Finally, there are data to suggest that blacks are overrepresented among patients with AIH undergoing liver transplantation in comparison with other ethnic groups.30

An interesting and novel observation of this study was that the worst outcomes were seen in black male patients. The 7 black males in this study were considerably younger (the mean age was 24.1 years) than the rest of the cohort. Four individuals (57.1%) presented with liver failure, and 6 (85.7%) were eventually referred or evaluated for a liver transplant. An earlier study reported that Somalian men with AIH were more likely to present with cholestatic features and respond poorly to standard immunosuppressive regimens than their white counterparts.31 These observations and the potential mechanisms merit further prospective corroboration and research.

There are conflicting data on the impact of cirrhosis on the natural history of AIH. One study reported similar outcomes in those with and without cirrhosis at the initial presentation or during the follow-up.6 Another study observed that the group that did poorly consisted of those who developed cirrhosis during follow-up.4, 32 In contrast, Feld et al.7 reported that cirrhosis at presentation was associated with a poorer outcome. The small sample sizes and heterogeneity of the patient population could explain the conflicting data. We did not stratify our cohort into cirrhosis at presentation versus cirrhosis during follow-up. We nonetheless observed that the presence of cirrhosis was an independent predictor of a poor outcome, and this was supported by the Kaplan-Meier analysis.

In conclusion, treatment responses and outcomes in AIH are determined in part by ethnicity. Blacks are twice as likely to be referred for liver transplantation and have a 4-fold increased risk of death. The reasons for this are probably multifactorial, including more aggressive and advanced disease at presentation, a poor initial response to medical therapy, and finally a genetic predisposition that could be immunologically mediated. The cohort with the worst outcome appears to be black males. Extra vigilance, close monitoring, and early liver transplantation may improve the outcomes. Additionally, these observations should stimulate further research to understand the mechanisms behind the poor response and thus to develop better treatment protocols for blacks with AIH.

Acknowledgements

S. Verma is grateful to Dr. Alan Redeker for his excellent critique of the manuscript.