Late toxicity-related symptoms and fraction dose affect decision regret among patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy for head and neck cancer

Abstract

Background

Decision regret reflects patient satisfaction with treatment choice and is associated with quality of life. This study aimed to identify patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics and post-treatment symptoms associated with decision regret among patients with head and neck cancer who underwent surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, patients completed a questionnaire during a telephone interview. The questionnaire included the Decision Regret Scale (DRS) and several specific symptom-related items. By the time of data collection, all patients had concluded their radiotherapy a minimum of 2 months and maximum of 3.3 years prior.

Results

Among the 108 patients included, 40.5% reported no regret, 30.1% reported mild regret, and 29.4% reported moderate to strong regret. A higher DRS score was most strongly associated with a lower single fraction dose and more restriction in everyday life. Higher DRS scores were also correlated with trouble speaking, trouble swallowing, pain in irradiated areas, dissatisfaction with one's appearance, feeling sad, and worry over one's future health.

Conclusions

Based on these findings, we recommended that patients with head and neck cancer undergoing adjuvant radiation receive psychosocial support and adequate treatment of late toxicity-related symptoms. When confronted with different therapeutic options, radiotherapy with a higher single fraction dose (i.e., hypofractionation) may be preferred due to its association with lower decision regret.

Abbreviations

-

- CLDP

-

- cervical lymphatic drainage pathways

-

- DRS

-

- Decision Regret Score

-

- HNC

-

- head and neck cancer

-

- HPV

-

- human papillomavirus

-

- MDASI-HN

-

- M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory – Head and Neck

-

- QoL

-

- quality of life

-

- VIF

-

- variance inflation factor

1 INTRODUCTION

Head and neck cancer (HNC) affects almost 900 000 individuals worldwide each year.1 The heterogeneity in patient characteristics and tumor features and locations presents challenges to developing standardized, consensus-based treatment guidelines for HNC. Instead, highly individualized therapy programs are devised for patients with HNC by specialized interdisciplinary health care teams to achieve a singular goal: complete resection or destruction of tumor tissue with the highest possible preservation of existing anatomical structures and function as well as patient quality of life (QoL). To maximize their QoL when multiple therapeutic options are feasible, patients can co-determine their therapy program through shared decision-making, during which the patient and health care providers discuss treatment options and mutually decide upon the best course of action.2

Although shared decision-making, when possible, provides patients with a certain freedom of choice, the partial responsibility of choosing their own therapy program can lead to more regret upon reflection on their decision. As decision regret is associated with worse QoL after therapy,11 it is vital to identify patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics and post-therapy symptoms that influence QoL to reduce the extent of decision regret that may be experienced.3

Reducing the extent of decision regret experienced by patients with HNC after radiotherapy could be achieved through different approaches. One approach is to reduce late treatment-related toxicity by using more sophisticated therapeutic technologies and considering different treatment modalities.4 In particular, techniques such as image-guided radiotherapy, intensity-modulated radiotherapy, forward and adaptive planning, and helical tomotherapy can reduce the intensity of radiation rays in peritumoral healthy tissue.5-9 Indeed, one study shows that reductions in radiotherapy dose to organs-at-risk decreases dry mouth in patients with various types of HNC and improves QoL in patients with oropharynx cancer.10 Another approach is to select specific therapy parameters during the planning phase or provide different types of post-therapy care based on patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics that are predictive of post-therapy decision regret or reduced QoL. For instance, patient reports of “feeling sad,” “difficulty swallowing,” and “pain” as well as factors including tumor classification, particular therapeutic combinations, smoking status at diagnosis, and M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory for head and neck cancer (MDASI-HN) symptom scores are associated with decision regret among patients with oropharyngeal cancer.11 However, factors such as total radiation dose, single fraction dose, radiotherapy boost, or patient comorbidities were not included in the analysis.

To further inform the development of approaches to reduce the extent of decision regret experienced by patients with HNC after radiotherapy, the aim of this study was to identify patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics and post-therapy symptoms associated with decision regret among patients with HNC who underwent surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Questionnaire design

We designed a questionnaire to obtain HNC patient-reported information on mid- to long-term decision regret and symptom burden after surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. The questionnaire design was based on multiple guidelines and recommendations to achieve a high scientific standard and minimize potential bias.12-15

Given that most study participants were over 60 years of age, we limited the length of the questionnaire with the understanding that older adults have a shorter attention span than younger adults.16 A short questionnaire was also advantageous because many patients with HNC have problems speaking after surgery of the tongue, pharynx, or larynx. Also, some patients with HNC require voice prosthetics or are mute and depend on a family member to interpret or translate their answers. Therefore, to minimize the potential rate of withdrawal from the study due to communication problems, the questionnaire included only 24 items (Table A1).

Decision regret was assessed using the Ottawa Decision Regret Scale (DRS),17 a five-item scale with established internal consistency, reliability, and validity.18-21 As a validated German version of the DRS is not available, we translated items from the English version as accurately as possible. Total possible DRS scores ranged from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating no regret and 100 indicating a high degree of regret. As we focused the DRS items on decision regret pertaining to radiotherapy, we included two additional items to assess decision regret pertaining to surgery or chemotherapy, if applicable.

The remaining 17 questionnaire assessed symptom burden following radiotherapy. The development of these items was informed by validated tools for assessing overall QoL (i.e., QL-Index, EORTC QLQ-C30, SF-36) and HNC-specific symptoms (i.e., EORTC QLQ-H&N43, MDASI-HN, LENT-SOMA H&N).22-27

Fourteen items focused on the most severe or common radiotherapy-associated symptoms considering functional requirements prioritized by patients.4, 11, 28, 29 Two items pertained to patients' emotional state, and one item pertained to improvements in symptom burden after radiotherapy. All items were scored on a scale from 0 to 5.

2.2 Patient selection

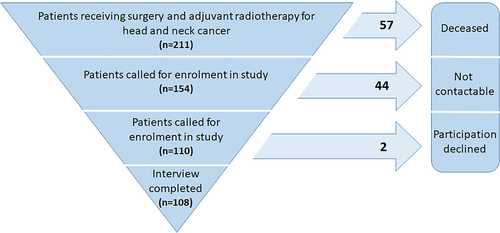

Patients who underwent surgery and adjuvant intensity-modulated radiotherapy with image guidance using helical tomotherapy for HNC between 1 January 2018 and 25 February 2021 were considered for inclusion in the study (Figure 1). However, patients with thyroid cancer were excluded due to its distinct histology and characteristics and availability of well-established, current treatment guidelines.30-32 Although patients receiving definitive radiation therapy were initially included, due to the small number of patients receiving this singular treatment modality, they were ultimately excluded from the analysis to achieve a more homogenous patient group treated with combined therapies.

Information on patient age; sex (male vs. female); radiotherapy boost (yes vs. no); duration of radiotherapy course; total radiation dose (≤60 Gy vs. >60 Gy); single fraction dose (≤2.0 Gy vs. >2.0 Gy); inclusion of cervical lymphatic drainage pathway (CLDP) or lymph nodes (none, unilateral, or bilateral); CLDP total dose (<60 Gy vs. ≥60 Gy); CLDP single fraction dose (<2.0 Gy vs. ≥2.0 Gy); number of surgeries (1, 2, or ≥3); neck dissection (none, unilateral, or bilateral); adjuvant chemotherapy (yes vs. no); adjuvant immunotherapy (yes vs. no); tumor grade (G; 1 or 2 vs. 3 or 4), size or extent (T; Tis/1, 2, 3, or 4), node (N; 0 or 1 vs. 2–4), and metastasis (M; 0 or 1) classification; tumor histology; primary tumor site; human papillomavirus status (negative vs. positive); history of or current tobacco use (yes vs. no) and number of pack-years, if applicable; alcohol consumption (no, yes, or abuse); number of comorbidities; treatment regimen and need for post-surgery voice prosthetics (yes vs. no) was obtained from the digital documentation system of the University Medical Center.

2.3 Questionnaire implementation

The questionnaire was completed with patients during a telephone call with a single interviewer using an interview protocol to reduce variations in patients' questionnaire and interview experiences. The interview was carried out within regular long-term medical aftercare. Although questionnaire items were formulated to be as clear as possible, we designed statements for clarification in case patients needed further explanation and to guarantee that all patients with similar questions received identical explanations from the interviewer. Nonetheless, it was necessary to deviate from the script in some cases due to the inherently unpredictable nature of interviews. Patient interviews began on 26 April 2021.

2.4 Statistical analysis

As DRS scores were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests, p < 0.001, df = 108), differences in DRS scores between patient subgroups were evaluated using Mann–Whitney U tests for dichotomous variables and Kruskal–Wallis tests for variables with more than two categories. Correlations between patient, tumor, and treatment and DRS scores were calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficients. Due to the large number of comparisons, Bonferroni correction was applied to minimize alpha inflation. The ability of specific patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics and symptom burden to predict DRS score was investigated using multiple linear regression.

3 RESULTS

Of the 211 patients identified, 57 (27.0%) died since undergoing radiotherapy. Of the remaining patients, 108 (70.1%) successfully completed the questionnaire. One patient withdrew during the interview for emotional reasons, but available data were included in the analysis to avoid drop-out bias. Among the 108 included patients, median age at diagnosis was 67 years (range, 34–96), and time since treatment was a median of 1.58 years (range, 0.18–3.21). Median total radiotherapy dose was 60.9 Gy (range, 20–72), and median single fraction dose was 2.1 Gy (range, 1.8–4.4).

The mean DRS score was 23.94 with a standard deviation calculated as 32.36. Following a previously published range for DRS score interpretation,32 40.5% of patients reported no regret (DRS = 0), 30.1% reported mild regret (DRS between 1 and 25), and 29.4% reported moderate to strong regret (DRS > 25). Cronbach's alpha for DRS questionnaire items was 0.945, reflecting high internal consistency within this patient group.

3.1 Correlations between patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics and decision regret

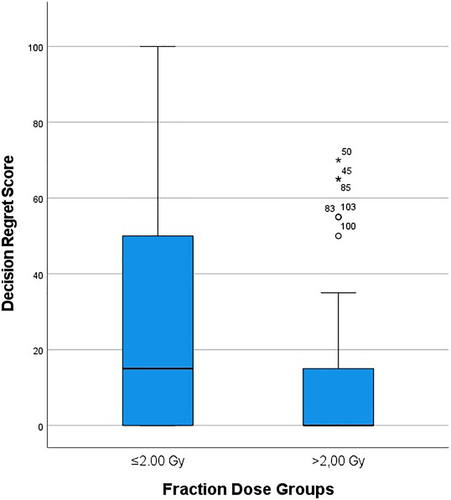

Single fraction dose was the only characteristic that was significantly associated with DRS score after Bonferroni correction (p = 0.044, r = 0.291) (Tables 1–3). Specifically, patients who received a single fraction dose >2.0 Gy had lower DRS scores than patients who received a single fraction dose ≤2.0 (Figure 2).

| N | Middle ranka | Rank sum | Mann–Whitney U | Z | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 37 | 57.58 | 2130.50 | 1199.50 | −0.764 | 0.445* |

| Male | 71 | 52.89 | 3755.50 | |||

| Radiotherapy boost | ||||||

| No | 23 | 60.43 | 1390.00 | 841.00 | −1060 | 0.289* |

| Yes | 85 | 52.89 | 4496.00 | |||

| Radiation dose | ||||||

| ≤60 Gy | 62 | 60.48 | 3749.50 | 1055.50 | −2.381 | 0.289 |

| >60 Gy | 46 | 46.45 | 2136.50 | |||

| Single fraction dose | ||||||

| ≤2.0 Gy | 63 | 61.94 | 3902.50 | 948.50 | −3.024 | 0.044 |

| >2.0 Gy | 45 | 44.08 | 1983.50 | |||

| CLDP dose | ||||||

| ≤60 Gy | 40 | 47.41 | 1896.50 | 803.50 | −1.201 | 0.230* |

| >60 Gy | 47 | 41.10 | 1931.50 | |||

| CLDP single fraction dose | ||||||

| <2.0 Gy | 38 | 47.49 | 1804.50 | 798.50 | −1.171 | 0.241* |

| ≥2.0 Gy | 49 | 41.30 | 2023.50 | |||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 66 | 56.34 | 3718.50 | 1264.50 | −0.792 | 0.428* |

| Yes | 42 | 51.61 | 2167.50 | |||

| Immunotherapy | ||||||

| No | 82 | 53.73 | 4405.50 | 1002.50 | −0.472 | 0.637* |

| Yes | 26 | 56.94 | 1480.50 | |||

| G classification | ||||||

| 1 or 2 | 51 | 58.39 | 2978.00 | 1000.00 | −2.230 | 0.442 |

| 3 or 4 | 52 | 45.73 | 2378.00 | |||

| N classification | ||||||

| 0 or 1 | 57 | 48.29 | 2752.50 | 1099.50 | −0.093 | 0.926* |

| 2–4 | 39 | 48.81 | 1903.50 | |||

| M classification | ||||||

| 0 | 62 | 31.97 | 1982.00 | 29.00 | −1.299 | 0.194* |

| 1 | 2 | 49.00 | 98.00 | |||

| Histology | ||||||

| Squamous | 101 | 54.02 | 5456.00 | 305.00 | −0.626 | 0.531* |

| Other | 7 | 61.43 | 430.00 | |||

| HPV status | ||||||

| Negative | 83 | 55.58 | 4613.50 | 947.50 | −0.678 | 0.498* |

| Positive | 25 | 50.90 | 1272.50 | |||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| No | 11 | 28.09 | 309.00 | 243.00 | −1.072 | 0.284* |

| Yes | 55 | 34.58 | 1902.00 | |||

| Voice prosthetic | ||||||

| No | 100 | 53.58 | 5358.00 | 308.00 | −1.117 | 0.264* |

| Yes | 8 | 66.00 | 528.00 | |||

- Abbreviations: CLDP, cervical lymphatic drainage pathway; DRS, Decision Regret Scale; G, tumor grade; HPV, human papillomavirus; N, nodal status.

- a The middle rank is a statistical value describing the average rank position of a subgroup within a population based on a specific attribute (i.e., decision regret).

- * p-value before Bonferroni correction.

| N | Middle ranka | Kruskal–Wallis H | df | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary tumor site | |||||

| Nasopharynx | 2 | 22.00 | 8.116 | 7 | 0.322* |

| Oropharynx | 17 | 46.59 | |||

| Hypopharynx | 7 | 51.29 | |||

| Larynx | 9 | 61.39 | |||

| Oral cavity | 51 | 57.91 | |||

| Nose/sinuses | 9 | 39.67 | |||

| Skin | 11 | 64.82 | |||

| Salivary glands | 2 | 57.50 | |||

| CLDP | |||||

| None | 21 | 53.60 | 1.093 | 2 | 0.579* |

| Unilateral | 29 | 59.47 | |||

| Bilateral | 58 | 52.34 | |||

| Number of surgeries | |||||

| One | 77 | 54.62 | 2.231 | 2 | 0.328* |

| Two | 21 | 48.60 | |||

| Three or more | 10 | 65.95 | |||

| Neck dissection | |||||

| None | 19 | 48.89 | 1.094 | 2 | 0.579* |

| Unilateral | 26 | 52.94 | |||

| Bilateral | 63 | 56.83 | |||

| Treatment regimen | |||||

| RT | 53 | 56.98 | 2.248 | 3 | 0.522* |

| RT + CT | 29 | 47.78 | |||

| RT + IMT | 13 | 53.73 | |||

| RT + ICT | 13 | 60.15 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| No | 19 | 24.29 | 0.408 | 2 | 0.815* |

| Yes | 11 | 25.73 | |||

| Abuse | 17 | 22.56 | |||

- Abbreviations: CLDP, cervical lymphatic drainage pathway; CT, chemotherapy; df, degrees of freedom; DRS, Decision Regret Scale; ICT, immunochemotherapy; IMT, immunotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

- a The middle rank is a statistical value describing the average rank position of a subgroup within a population based on a specific attribute (i.e., decision regret).

- * p-value before Bonferroni correction.

| Spearman's rho | p-value | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.052 | 0.595* | 108 |

| Radiotherapy duration | −0.085 | 0.384* | 108 |

| T classification | −0.093 | 0.343* | 105 |

| Smoking pack-years | 0.143 | 0.361* | 43 |

| Comorbidities | −0.135 | 0.165* | 108 |

- Abbreviations: DRS, Decision Regret Scale; T, tumor size or extent.

- * p-value before Bonferroni correction.

3.2 Correlations between symptom burden and decision regret

A high DRS score was significantly correlated with more restriction in everyday life (p < 0.001, r = 0.548), pain in the irradiated areas (p < 0.001, r = 0.495), worry about future health (p < 0.001, r = 0.481), dissatisfaction with one's appearance (p < 0.001, r = 0.420), feeling of sadness (p < 0.001, r = 0.388), trouble speaking (p = 0.034, r = 0.291), and trouble swallowing since radiotherapy (p = 0.049, r = 0.285) (Table 4). Breathing problems, less sense of taste, hearing loss, trouble chewing, dental problems, persistent skin problems, wound healing problems, dry mouth, hoarseness, and feeling better since radiotherapy were not correlated with DRS score (p > 0.05).

| Spearman's rho | p-value | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Everyday life | 0.548 | <0.001 | 108 |

| Speaking | 0.291 | 0.034 | 108 |

| Breathing | 0.215 | 0.442 | 107 |

| Taste | 0.115 | 0.236* | 108 |

| Hearing | 0.173 | 0.073* | 108 |

| Chewing | 0.233 | 0.272 | 107 |

| Dental | 0.179 | 0.065* | 107 |

| Swallowing | 0.285 | 0.049 | 107 |

| Skin | 0.198 | 0.697 | 107 |

| Wound healing | 0.146 | 0.133* | 107 |

| Dry mouth | 0.196 | 0.731 | 107 |

| Pain | 0.495 | <0.001 | 107 |

| Hoarseness | 0.161 | 0.097* | 107 |

| Appearance | 0.420 | <0.001 | 108 |

| Worry about future health | 0.481 | <0.001 | 107 |

| Sadness | 0.388 | <0.001 | 107 |

| Feeling better | −0.204 | 0.578 | 108 |

- Abbreviation: DRS, Decision Regret Scale.

- * p-value before Bonferroni correction.

3.3 Factors predicting decision regret

As linear regression only produces conclusive and meaningful results when a limited number of independent variables are involved,33 we included only significant factors (after Bonferroni correction) in multiple linear regression analysis. The model was statistically significant (F(8, 98) = 8.340; p < 0.001) with a coefficient of determination (R) of 0.636 (Table 5), indicating a very strong association between the independent variables and DRS score.34 The variance explained (R2) was 0.405. To further adjust for the number of terms included in the model, we calculated adjusted R2 (0.356), which indicated that the independent variables explained a high amount of variance in DRS score.35

| Nonstandardized regression coefficient | Standard error | Standardized beta coefficient | p-value | Tolerance | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 12.227 | 4.644 | 0.010 | |||

| Everyday life | 3.833 | 1.800 | 0.229 | 0.036 | 0.526 | 1.900 |

| Speaking | 0.069 | 1.462 | 0.004 | 0.962 | 0.744 | 1.344 |

| Swallowing | 1.390 | 1.514 | 0.085 | 0.361 | 0.711 | 1.407 |

| Pain | 3.278 | 2.107 | 0.149 | 0.123 | 0.660 | 1.515 |

| Appearance | 3.068 | 1.603 | 0.181 | 0.059 | 0.677 | 1.478 |

| Worry about future health | 0.388 | 1.640 | 0.023 | 0.813 | 0.635 | 1.575 |

| Sadness | 2.196 | 1.877 | 0.109 | 0.245 | 0.705 | 1.419 |

| Single fraction dose | −16.678 | 5.092 | −0.261 | 0.001 | 0.954 | 1.049 |

- Abbreviations: DRS, Decision Regret Scale; VIF, variance inflation factor.

Although the entire model was significant, only two independent variables were significantly associated with DRS score: restriction in everyday life (p = 0.036; nonstandardized regression coefficient = 3.833; standardized beta coefficient = 0.229) and single fraction dose (p = 0.001; nonstandardized regression coefficient = −16.678; standardized beta coefficient = −0.261). Specifically, a higher DRS score was correlated with more restriction in everyday life and a lower single fraction dose. Although the independent variables included in the model likely possess some degree of multicollinearity due to their hypothetically shared origin from radiotherapy (and possibly surgery), neither tolerance nor variance inflation factor values suggest notable multicollinear processes.36

After bootstrapping with 1000 samples to ensure model robustness against statistical outliers, both restriction in everyday life (p = 0.039) and single fraction dose (p = 0.003) remained significant, and all other variables retained their approximate p-values and regression coefficients, further confirming the analysis results.

3.4 Association between surgery or chemotherapy decision regret and radiotherapy decision regret

Of the 108 patients who underwent surgery, 99 (91.7%) reported no regret over their decision to undergo surgery, whereas 8 (7.4%) regretted at least one of the performed surgeries. One patient (0.9%) did not answer this question. Patients who regretted surgery had higher DRS scores (middle rank = 75.75) than patients who did not regret surgery (middle rank = 52.24; Mann–Whitney U = 222.00, Z = −2.134, p = 0.033). As only 3 (6.7%) of the 45 patients who underwent chemotherapy reported regret over their decision to undergo chemotherapy, statistical analysis was not performed due to the small number of observations.

4 DISCUSSION

We investigated decision regret among patients with HNC who underwent surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy and its association with patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics and the burden of specific symptoms. Over half (59.5%) of patients reported experiencing some degree of decision regret, and over a quarter (29.4%) reported experiencing moderate to strong decision regret.

Symptom burden has long been suspected to be a major driver of decision regret,11 but few studies have distinguished between different symptoms.37 Also, some studies only assessed patients' priorities before therapy or correlated symptoms with QoL rather than decision regret.9, 27, 28 In the present study, we found that five specific post-therapy symptoms (restriction in everyday life, trouble speaking, trouble swallowing, pain in irradiated areas, dissatisfaction with appearance), two emotional states (sadness and worry over future health), and one treatment characteristic (single fraction dose) were associated with decision regret among patients with HNC. Correlations between decision regret and pain, sadness, and feeling distressed or upset were reported by a previous study that analyzed some therapy characteristics and symptoms using items from the MDASI-HN.11 However, somewhat different from our results, this previous study found very strong correlations between decision regret and dry mouth, difficulty swallowing, teeth/gum problems, and coughing. As this previous study included only patients with oropharyngeal cancer, their symptoms were possibly more prevalent and severe due the particular tumor localization.11 Although our regression model explained a high amount (36%) of variance in decision regret, the remaining variance must be attributed to other factors that were not investigated in the present study. Furthermore, as correlation is not a unidirectional concept, it remains possible that sadness and worry about future health, for example, may not be the cause but rather the outcome of decision regret. Thus, further research on the psychological aspects of decision regret is needed to advance our understanding of how to properly manage decision regret in post-therapeutic care. Patients' social situation as a potentially stabilizing factor after radiotherapy should also be investigated.

We found that the strongest contributor to decision regret among patients with HNC was restriction in everyday life. Therefore, patients should be questioned before therapy to assess their individual priorities and social situation, which should be accommodated through a suitable therapy choice. Pain in the irradiated areas also contributed to decision regret, suggesting that pain management after radiotherapy is important for reducing decision regret and improving patients' QoL. Similar to a previous study,11 we also found that symptoms such as trouble speaking or swallowing as well as feeling sad are associated with decision regret. However, post-radiotherapy symptoms such as dry mouth and loss of taste were not strongly associated with decision regret despite their frequency and severity among patients with HNC.

Considering patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics, only single fraction dose was associated with decision regret. Specifically, a single fraction dose >2.0 Gy was associated with less decision regret, suggesting a possible benefit of hypofractionated radiation courses. The exact fraction doses comprising this group (>2.0 Gy) in our study were 2.1, 2.2, and 3.0 Gy. Hypofractionation is considered to be well-tolerated in patients with HNC, contributing to better local control and reducing early toxicity.38, 39 As improved tumor control likely leads to increased survival and reduced symptom burden, these findings support the use of hypofractionation in situations where multiple therapeutic strategies are viable.

This study has some additional limitations that must be considered. First, the study involved a small number of patients with different disease sites and severities, which could serve to mask potential differences among patient subgroups or limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, as we assessed relationships between patient- and treatment-related factors and decision regret between 2 months and 3.3 years after radiotherapy, it is unclear whether these relationships persist over a longer period of survivorship. However, a previous study of patients with breast cancer reports that the degree of treatment-related decision regret as well as relationships among treatment characteristics and decision regret remain largely stable between ~9 months post-diagnosis and 4 years later.40 Third, although we took measures to keep the questionnaire brief, to ensure that questionnaire items would be clearly understood by patients, and to standardize questionnaire and interview experiences across patients, it remains possible that the interviews were prone to biases influenced by factors such as patients' communication ability, attention span, and desire to report positive feelings. Lastly, as our questionnaire was self-constructed, it may be less valid than other widely used standardized questionnaires. However, content validity was achieved through strict definition of item goals and expert consensus on both the construction and selection of content, and construct validity was achieved by using pre-existing validated questionnaires and item pools as inspiration and guidance. Nevertheless, independent validation of our questionnaire would further help confirm our findings.

5 CONCLUSION

This study is one of the first to evaluate decision regret in patients with HNC who underwent surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy and to explore its association with patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics and symptom burden. The two factors most strongly associated with decision regret were restriction in everyday life and a low single fraction dose (≤2.0 Gy). We recommended that health care providers identify a patient's priorities in everyday life and plan multimodal therapy accordingly. When confronted with several potential therapy options, hypofractionation may be preferred. This study makes an important contribution to the current literature, as highly individualized therapy programs that optimize medical care and fit patients' personal needs form the current standard for HNC. Future investigations of psychological aspects of decision regret, its social context, and the impact of combined therapies will help contextualize these results and further enhance our understanding of the origin of and interactions between decision regret and its causes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants, including participants provision of an informed consent prior to enrolment in the study, were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional Ethics committee approval number 024/21 dated 22 January 2021 and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

APPENDIX A

| Last name, First name: ____________________________________________________ Birth date: ______________ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| A little | A lot | ||||||

| My everyday life has been restricted since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have trouble speaking since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have new breathing problems since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have less sense of taste since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have hearing loss since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have trouble chewing since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have problems with my teeth since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have trouble swallowing since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have persistent skin problems since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have wound healing problems since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have dry mouth since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have pain in the irradiated areas | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have problems with hoarseness since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am dissatisfied with my appearance since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am worried about my future health | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have felt sad since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I feel better despite my physical ailments since the radiation therapy | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Decision = decision to undergo radiation therapy | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It was the right decision | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| I regret the choice that was made | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| I would go for the same choice if I had to do it over again | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| The choice did me a lot of harm | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| The decision was wise | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Yes | No | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I regret having chemotherapy (if applicable) | ☐ | ☐ | |||||

| I regret having surgery | ☐ | ☐ |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.