Variations in concerns reported on the patient concerns inventory in patients with head and neck cancer from different health settings across the world

Abstract

Background

The aim was to collate and contrast patient concerns from a range of different head and neck cancer follow-up clinics around the world. Also, we sought to explore the relationship, if any, between responses to the patient concerns inventory (PCI) and overall quality of life (QOL).

Methods

Nineteen units participated with intention of including 100 patients per site as close to a consecutive series as possible in order to minimize selection bias.

Results

There were 2136 patients with a median total number of PCI items selected of 5 (2-10). “Fear of the cancer returning” (39%) and “dry mouth” (37%) were most common. Twenty-five percent (524) reported less than good QOL.

Conclusion

There was considerable variation between units in the number of items selected and in overall QOL, even after allowing for case-mix variables. There was a strong progressive association between the number of PCI items and QOL.

1 INTRODUCTION

The number of cancer cases across the world increased by one third between 2005 and 2015. The main influences were population growth and increasing age.1 In 2018, there will be over 18 million new cancer cases and nearly 10 million cancer deaths.2 Head and neck cancer (HNC) is a global problem and rates continue to climb with the increase in number of oropharyngeal cancers ascribed to human papillomavirus.3

Patient reported outcome measures (PROM) are an established component of cancer outcomes reporting.4 Publications related to PROM reflect international interest with papers from Africa, Asia, Australia/Oceania, Europe, North America, and South America. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) assessment is embedded in many clinical trials.5 Over 6000 patients with cancer pooled from randomized controlled trials and using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 showed differences between cancer types and the effects of age on HRQOL.6 In a critical review, Aggarwal et al summarized global radiation therapy research between 2001 and 2015, and reported increasing numbers of HRQOL papers from a range of different countries.7

HRQOL evaluation makes a positive difference in clinical practice 8 and research around the expression of concerns during follow-up consultations is ongoing.9 This approach supports patient-centered interventions. 10 Following HNC treatment, there is a large array of potential issues patients wish to discuss. This led to the development of the patient concerns inventory (PCI) as an item prompt list to aid clinical consultations and promote multiprofessional involvement for patients.11 There are subtle differences in items and their frequency reported by HNC patients by site (oral, oropharyngeal, laryngeal, and other) and stage (early, late).12

Most publications relating to the PCI have been UK based and thus far there is a lack of evaluation across a wide variety of healthcare settings. There are likely to be clinical, social, cultural, spiritual, and health economic variances. Recognizing concerns common across centers and reflecting on differences should aid clinicians and their colleagues from multiprofessional backgrounds to consider ways to improve the post-treatment support for patients.

The aim of this project was to collate and contrast PCI responses from a range of different head and neck cancer follow-up clinics around the world. Also, we sought to explore the relationship, if any, between responses to the PCI and overall quality of life (QOL).

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

Nineteen units from around the globe participated (Table 1) and Aintree University Hospital in Liverpool was the lead co-ordinating site. The intention was to acquire at least 100 patients per site and as close to a consecutive series as possible to minimize selection bias. The sample size was a pragmatic decision based on the likely number of patient responses achievable within a reasonable timeframe. Eligible patients were those following head and neck cancer treatment, aged 18 to 89 years, and attending routine clinic consultations. Patients were free from active cancer (no time limit) and their treatment was with curative intent. Those successfully treated for recurrence and late effects such as osteoradionecrosis were also eligible. Patients were ineligible if they had cognitive impairment, significant psychiatric illness, or with thyroid or skull base cancer. Eligible patients attending several clinics were only included once. Units were aware of patient identity but their submitted data was anonymous. Collaborators approached local medical health boards or University Institutes regarding local ethical approval and sponsorship and receipt of such approval was required centrally. The data collection period was in large part during 2018, when the data was submitted to Aintree. The exception was Aintree itself with consecutive cases from November 2011 to January 2013; this was because Aintree is currently involved in a randomized trial of the PCI.

| Abbreviated description | Description | Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Royal Brisbane Hospital | 100 |

| Belgium | Unit Liège | 203 |

| Brazil | Unit, Rio de Janeiro | 77 |

| Chile | Instituto Nacional del Cancer, Santiago | 100 |

| France | Gettec French Group | 204 |

| Germany | Unit, Göttingen | 140 |

| India-A | Amrita Institute, Kochi, Kerala | 100 |

| India-T | Tata Memorial Hospital | 100 |

| Italy | University Hospital of Modena | 117 |

| Malaysia | University of Malaya | 58 |

| Poland | Wrocław Medical University | 79 |

| Romania | Emergency County Hospital, Cluj-Napoca | 103 |

| Serbia | University of Nis | 100 |

| Sweden-S | Sahlgrenska University Hospital Gothenburg | 108 |

| Sweden-U | Umeå University Hospital and Uppsala University Hospital | 89 |

| Taiwan | Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital | 157 |

| Turkey | University of Istanbul | 103 |

| UK-L | Aintree Hospital Liverpool | 148 |

| UK-S | Morriston Hospital Swansea | 50 |

| Total | 2136 |

The PCI as developed at Aintree University Hospital in collaboration with Edge Hll University and consists of 56 specific clinical items (see Figure 5 to see a list of items) and one free-text “others” box, and is an item prompt list which patients select from before their appointment. These items can be grouped within domains 13 of physical and functional well-being (29 items), treatment related (4 items), social care and social well-being (9 items) and psychological, emotional, and spiritual well-being (14 items). The PCI also contains a list of 18 professionals who patients might want to talk with. For this international study, this list was excluded because it is specific to the United Kingdom and job roles and titles do vary between countries. Thus, only a single sheet paper version of the PCI symptom and problem prompt list was created. Also, a single question about QOL was included for analysis in relation to the PCI. The overall QOL question from The University of Washington QOL questionnaire (UW-QOLv4) was chosen and this asks patients to rate their overall QOL during the past 7 days.14 Patients are asked to consider not only physical and mental health, but also other factors, such as family, friends, spirituality, or personal leisure activities important to their enjoyment of life. The response options for the overall QOL question are “outstanding,” “very good,”’ good,’ “fair,” “poor,” and “very poor,” The main reason for including this single question about QOL was that the primary outcome measure in an ongoing multicenter randomized trial9 is the percentage of patients reporting less than good overall QOL. The analyses we present use this dichotomy, that is, where the responses of “fair,” “poor,” and “very poor” are taken as being “less than good.” The PCI and UW-QOLv4 have already been translated into various languages and these were used to create the single page form used in this study. Where there were no translated versions, a standard forward and backward translation process was followed with consensus for any discrepancies.

Units collected categorical clinical and demographic details on each patient for age (<55, 55-64, 65-74, ≥75), sex (men, women), clinical stage (early stage 1-2 or late stage 3-4), site (oral, oropharynx, larynx, other), surgery (yes, no), radiotherapy (yes, no), chemotherapy (yes, no), and months from primary diagnosis (<12, 12-23, 24-59, ≥60). Each unit entered data into a preprepared excel worksheet which was submitted centrally via secure email for collation into a single SPSS (Version 25) dataset.

2.1 Statistical method

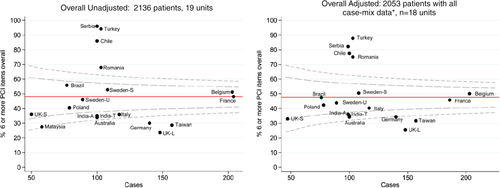

Given the skewed nature of the number of PCI items selected, both in total and particularly in the domains, we created binary PCI variables with the cut-off determined by the median number of items selected. This approach avoided any subjective selection of cut-off values and allowed for consistency of approach across domains in analysis and presentation. Funnel plots presenting the percentage of patients selecting more than the median value for the study sample as a whole are shown for each unit against their number of cases. A red reference line represents the overall percentage of patients who reported more than the median number of PCI items. Control limits are often shaped like a “funnel” and serve as boundaries15 that represent the bounds of statistical confidence around the average value. Unit results outside these boundaries can be considered outliers in that the chance of results being there due to chance alone is very small (0.2%) for the outer limits, slightly higher (5%) for the inner limits. When unit results do fall outside, these are inconsistent with the overall sample result in relation to their sample size, implying that something else (nonrandom) is happening, for example, systematic organizational, quality of care, or cultural differences. Some funnel plots present unit variation per se and others after case-mix adjustment. This adjustment was achieved using logistic regression modeling with each binary PCI variable in turn as the dependent variable and the case-mix variables as independent predictors. The case-mix variables for this and other adjustment analyses in this article were age (<55, 55-64, 65-74, ≥75), sex (men, women), clinical stage (early stage 1-2 or late stage 3-4), site (oral, oropharynx, larynx, other), treatment (surgery only, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy without surgery, surgery with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy), and months from primary diagnosis (<12, 12-23, 24-59, ≥60). Expected patient probabilities were derived from each regression, and were summed over the set of patients for each unit to give expected patient numbers. The observed to expected ratio of numbers for each unit multiplied by the overall sample rate gave the adjusted rate for each unit. Funnel plots were similarly constructed showing the percentage of patients reporting less than good overall QOL.

Binary regression (STATA binreg procedure, rr link option) was used to assess the association of case-mix to PCI (total items selected and by domain) and to overall QOL being less than good. Risk ratios were estimated as were 95% confidence intervals, with adjustments made for other case-mix variables as independent predictors and for unit clustering effects (by using the option “cluster”). Binary regression with adjustment for unit clustering was also performed for each of the PCI items in turn as a predictor of overall QOL being less than good.

The study co-ordinator received ethical approval documents from each individual unit. Over-arching ethical approval was gained from West of Scotland Research Ethics Service; IRAS project ID: 234413, REC reference: 18/WS/0152. The study was unfunded.

3 RESULTS

Nineteen units participated with a median (IQR) of 100 (89-140) cases submitted, range 50 to 204, in total, data were submitted on 2136 patients, and 70% (1488/2135) were males. Twenty-four percent (505/2132) were aged under 55 years, with 32% (686) 55 to 64 years, 32% (672) 65 to 74 years, and 13% (269) 75 years or older. Just over half (55%, 1157/2115) had “late” stages 3 to 4 tumors, and tumor location for 48% (1025/2129) was oral, 20% (424) oropharynx, 20% (419) larynx, and 12% (261) “other.” About one-third (36%, 763/2122) were treated by surgery alone, 23% (482) by radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy without surgery, while 41% (877) had surgery combined with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Specifically, 77% (1642/2131) received surgery, 62% (1326/2130) radiotherapy, and 32% (689/2128) chemotherapy. One quarter (27%, 560/2073) were within 12 months of diagnosis, 20% (416) within 12 to 23 months, 30% (620) within 24 to 59 months, and 23% (477) at 60 months or later.

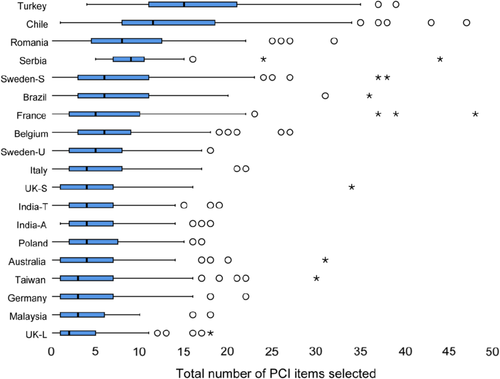

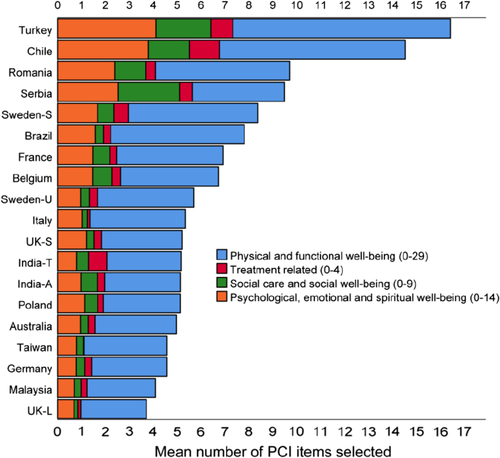

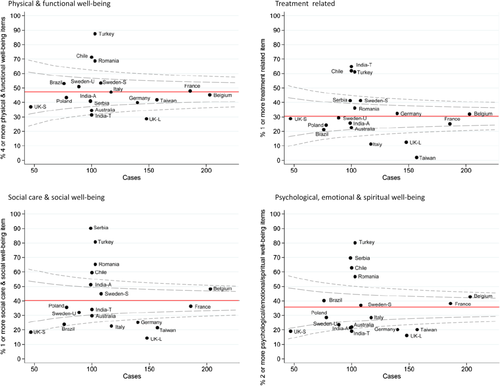

The median (IQR) total number of PCI items selected was 5 (2-10), range 0 to 48 items, mean 6.95 and 48% (1026/2136) with six or more PCI items overall. Corresponding results for each PCI domain were: Physical and functional well-being 3 (1-6), 0-28, 4.31, and 47% (1013/2136) with four or more items; Treatment related 0 (0-1), 0-4, 0.38, and 31% (665/2136) with one or more items; Social care and social well-being 0 (0-1), 0-9, 0.75, and 41% (869/2136) with one or more items; Psychological, emotional, and spiritual well-being 1 (0-2), 0-13, 1.50, and 36% (773/2136) with two or more items. There was considerable variation between units in the number of items their patients selected (Figure 1), and a fourfold difference in the mean total number selected (Figure 2). However, there was considerable variation in unit case-mix (Table 2). Figure 3 presents funnel plots showing unit variation both before and after case-mix adjustment in the number of patients selecting six or more PCI items overall. Case-mix adjustment had minimal impact on unit variation implying there remain stronger systematic unit differences. Figure 4 shows case-mix adjusted funnel plots for PCI domains and though most units follow the pattern delineated by the funnel some units had a tendency for their patients to select more items across all domains, and others to select fewer. One unit was excluded from all adjusted analyses because no data was submitted for one of the case-mix variables (Table 2).

| Sex | Age | Stage | Tumor site | Treatment | Time from diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean # PCI items | Cases | No. (%) female | No. (%) ≥65 years | No. (%) Late | No. (%) oral | No. (%) oro-pharynx | No. (%) larynx | No. (%) other location | No. (%) surgery alone | No. (%) RT/CT without surgery | No. (%) Surgery and RT/CT | No. (%) ≥24 months | |

| Turkey | 16.4 | 103 | 40 (39) | 20 (19) | 71 (69) | 90 (87) | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 4 (4) | 32 (31) | 5 (5) | 66 (64) | 64 (62) |

| Chile | 14.5 | 100 | 51 (51) | 24 (24) | 55 (55) | 57 (57) | 4 (4) | 10 (10) | 29 (29) | 56 (56) | 9 (9) | 35 (35) | 15 (15) |

| Romania | 9.7 | 103 | 11 (11) | 43 (42) | 47 (46) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 76 (74) | 24 (23) | 38 (37) | 20 (19) | 45 (44) | 62 (60) |

| Serbia | 9.5 | 100 | 49 (49) | 48 (48) | 57 (57) | 78 (78) | 22 (22) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14/99 (14) | 16/99 (16) | 69/99 (70) | 36 (36) |

| Sweden-S | 8.4 | 108 | 35 (32) | 41 (38) | 31 (29) | 15 (14) | 76 (70) | 8 (7) | 9 (8) | 8 (7) | 92 (85) | 8 (7) | 62 (57) |

| Brazil | 7.8 | 77 | 15 (19) | 46 (60) | 59 (77) | 30 (39) | 12 (16) | 33 (43) | 2 (3) | 28/76 (37) | 20/76 (26) | 28/76 (37) | 0 (0) |

| France | 6.9 | 204 | 62/203 (31) | 106/203 (52) | 121/197 (61) | 50/200 (25) | 63/200 (32) | 51/200 (26) | 36/200 (18) | 31/198 (16) | 60/198 (30) | 107/198 (54) | 119/200 (60) |

| Belgium | 6.7 | 203 | 54 (27) | 112 (55) | 122 (60) | 39 (19) | 81 (40) | 69 (34) | 14 (7) | 53 (26) | 70 (34) | 80 (39) | 107 (53) |

| Sweden-U | 5.7 | 89 | 17 (19) | 44 (49) | 62 (70) | 18 (20) | 48 (54) | 12 (13) | 11 (12) | 10 (11) | 50 (56) | 29 (33) | 31 (35) |

| Italy | 5.4 | 117 | 34 (29) | 73 (62) | 74 (63) | 41 (35) | 28 (24) | 41 (35) | 7 (6) | 57 (49) | 29 (25) | 31 (26) | 81 (69) |

| UK-S | 5.2 | 50 | 15 (30) | 26/48 (54) | 30 (60) | 43 (86) | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 22/49 (45) | 4/49 (8) | 23/49 (47) | 16 (32) |

| India-T | 5.2 | 100 | 14 (14) | 15 (15) | 67 (67) | 75 (75) | 6 (6) | 8 (8) | 11 (11) | 9 (9) | 20 (20) | 71 (71) | 85 (85) |

| India-A | 5.1 | 100 | 25 (25) | 35 (35) | 36 (36) | 56 (56) | 1 (1) | 6 (6) | 37 (37) | 36/99 (36) | 1/99 (1) | 62/99 (63) | 47 (47) |

| Poland | 5.1 | 79 | 21 (27) | 49 (62) | 66 (84) | 5 (6) | 4 (5) | 55 (70) | 15 (19) | 43/78 (55) | 28/78 (36) | 7/78 (9) | 40 (51) |

| Australia | 5.0 | 100 | 41 (41) | 50/99 (51) | 49 (49) | 91 (91) | 6 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 57 (57) | 3 (3) | 40 (40) | 47 (47) |

| Taiwan | 4.6 | 157 | 12 (8) | 43 (27) | 88 (56) | 99 (63) | 28 (18) | 9 (6) | 21 (13) | 63 (40) | 29 (18) | 65 (41) | 118 (75) |

| Germany | 4.6 | 140 | 64 (46) | 67 (48) | 45 (32) | 124 (89) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (11) | 109 (78) | 0 (0) | 31 (22) | 83 (59) |

| Malaysia | 4.4 | 58 | 39 (67) | 25 (43) | 11/44 (25) | 53/55 (96) | 0/55 (0) | 0/55 (0) | 2/55 (4) | 25/55 (45) | 3/55 (5) | 27/55 (49) | No data |

| UK-L | 3.7 | 148 | 48 (32) | 73 (49) | 66 (45) | 61 (41) | 35 (24) | 35 (24) | 17 (11) | 72 (49) | 23 (16) | 53 (36) | 83/147 (56) |

| Overall | 7.0 | 2136 | 647/2135 (30) | 940/2132 (44) | 1157/2115 (55) | 1025/2129 (48) | 424/2129 (20) | 419/2129 (20) | 261/2129 (12) | 763/2122 (36) | 482/2122 (23) | 877/2122 (41) | 1096/2073 (53) |

- Abbreviation: No, number of patients.

Binary regression assessed the association of each case-mix variable with the likelihood of endorsing more than the median number of PCI items, after adjustment for other case-mix variables as independent predictors and adjustment for unit clustering. Separate models evaluated each PCI score (ie, total score, physical function, treatment-related issues, social care/social well-being, and psychological/emotional/spiritual well-being; Table 3). The first column of results shows univariate case-mix variable variation in the percentage of patients selecting ≥6 PCI items overall and greater percentages were observed for females, patients with later stage tumors, patients having radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, and patients within 12 months of diagnosis. Overall and across domains, the adjusted risk ratios suggest a consistency for females to be more likely to select more items, particularly psychological emotional and spiritual items, though some of the confidence intervals about these risk ratios did include the possibility of no added risk (ie, a risk ratio of 1.00). Similarly, there was also consistency observed in risk ratios greater than 1.00 for patients treated with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, and patients within the first 12 months since diagnosis, though again many of the confidence intervals included the possibility of no added risk. There generally seemed little association with tumor site while tumor stage seemed more specifically relevant to physical functioning.

| ≥6 PCI items selected overall | ≥4 Physical function items selected | ≥1 Treatment-related issues selected | ≥1 Social care and social well-being items selected | ≥2 Psychological, emotional, and spiritual well-being items selected | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw data | Risk ratioa unadjusted | Risk ratioa after adjustment | Risk ratioa after adjustment | Risk ratioa after adjustment | Risk ratioa after adjustment | Risk ratioa after adjustment | ||

| Sex | Men | 45% (665/1488) | Reference | |||||

| Women | 56% (360/647) | 1.25 (1.14-1.36) | 1.28 (1.11-1.47) | 1.26 (1.13-1.41) | 1.06 (0.82-1.37) | 1.11 (0.93-1.33) | 1.45 (1.24-1.68) | |

| Age at diagnosis | <55 | 48% (242/505) | Reference | |||||

| 55-64 | 50% (346/686) | 1.05 (0.94-1.18) | 1.04 (0.90-1.19) | 1.04 (0.88-1.24) | 0.80 (0.67-0.96) | 0.97 (0.84-1.11) | 0.94 (0.77-1.15) | |

| 65-74 | 47% (318/672) | 0.99 (0.87-1.11) | 0.99 (0.83-1.19) | 1.01 (0.84-1.22) | 0.75 (0.57-0.99) | 0.87 (0.70-1.07) | 0.77 (0.60-0.99) | |

| ≥75 | 43% (117/269) | 0.91 (0.77-1.07) | 0.91 (0.70-1.19) | 1.06 (0.81-1.39) | 0.69 (0.44-1.07) | 0.81 (0.64-1.04) | 0.72 (0.53-1.00) | |

| Stage | Early | 41% (395/958) | Reference | |||||

| Late | 54% (624/1157) | 1.31 (1.19-1.43) | 1.13 (0.98-1.30) | 1.25 (1.09-1.45) | 0.98 (0.79-1.20) | 1.00 (0.84-1.20) | 1.09 (0.92-1.29) | |

| Site | Oral | 48% (490/1025) | Reference | |||||

| Oropharynx | 52% (219/424) | 1.08 (0.97-1.21) | 0.93 (0.79-1.10) | 1.04 (0.87-1.24) | 0.90 (0.64-1.28) | 0.72 (0.54-0.96) | 0.96 (0.69-1.34) | |

| Larynx | 45% (189/419) | 0.94 (0.83-1.07) | 0.94 (0.71-1.25) | 0.96 (0.75-1.22) | 0.94 (0.70-1.28) | 1.10 (0.79-1.53) | 1.10 (0.76-1.60) | |

| Other | 48% (124/261) | 0.99 (0.86-1.15) | 0.91 (0.70-1.17) | 0.95 (0.78-1.16) | 1.00 (0.70-1.42) | 0.89 (0.59-1.34) | 1.02 (0.72-1.43) | |

| Treatment | Surgery only | 37% (286/763) | Reference | |||||

| RT+/-CT only | 51% (246/482) | 1.36 (1.20-1.55) | 1.34 (1.04-1.74) | 1.23 (1.00-1.52) | 1.19 (0.76-1.86) | 1.17 (0.89-1.53) | 1.04 (0.77-1.39) | |

| Surgery and RT±CT | 56% (489/877) | 1.49 (1.33-1.66) | 1.41 (1.10-1.81) | 1.26 (1.04-1.52) | 1.31 (0.93-1.86) | 1.34 (1.04-1.72) | 1.20 (0.90-1.59) | |

| Time from diagnosis | <12 months | 56% (315/560) | Reference | |||||

| 12-23 months | 50% (206/416) | 0.88 (0.78-0.99) | 0.87 (0.72-1.05) | 0.90 (0.76-1.06) | 0.84 (0.64-1.11) | 0.89 (0.69-1.14) | 0.88 (0.66-1.18) | |

| 24-59 months | 42% (260/620) | 0.75 (0.66-0.84) | 0.74 (0.59-0.93) | 0.80 (0.64-0.99) | 0.73 (0.48-1.10) | 0.81 (0.64-1.03) | 0.77 (0.55-1.06) | |

| ≥60 months | 47% (225/477) | 0.84 (0.74-0.95) | 0.85 (0.68-1.06) | 0.84 (0.68-1.04) | 0.84 (0.55-1.29) | 0.83 (0.62-1.12) | 0.85 (0.62-1.16) | |

- Abbreviation: PCI, patient concerns inventory.

- a Risk ratio (with 95% confidence interval) for unadjusted and then adjusted for other case-mix factors and for within-unit clustering (n = 2053 with all case-mix known).

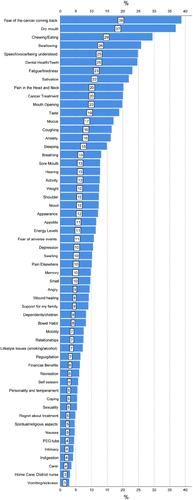

Figure 5 shows the PCI items selected by patients over the whole sample, the most common of which were “fear of the cancer returning” (39%) and “dry mouth” (37%). Other items selected by 20% to 29% of patients were “chewing/eating,” “swallowing,” “speech/voice/being understood,” “dental health/teeth,” “fatigue/tiredness,” “salivation,” “pain in the head and neck,” “cancer treatment,” and “mouth opening,” “Dry mouth” was in the top five items selected for 17 of the 19 units and in the top 10 items selected for 18 units (Table 4) and “fear of the cancer returning” was in the top 10 selected items for all 19 units. In all, across 19 units there were 20 different PCI items that made their way into the top five items selected and 35 items into the top 10 selected. Other free-text items were few in number (2%, 51/2136); three were related to work, three to itchy skin, and three to bad breath, whereas the remainder were a disparate collection of nonspecific issues, such as lip ulcer, tremor, postoperative hair growth in mouth, dimension of tracheostomy stoma, loneliness, facial numbness, cramps, aching joints, CT findings, and blocked tear duct.

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | Chewing/dry mouth/speech | Swallowing | Appearance | Anxiety/mouth O/salivation | Fear | Mood | ||||

| Chile | Fear | Cancer T | Dental | Dry mouth | Chewing | Speech | Wound H | Pain HN/swallowing | Salivation | |

| Romania | Speech | Fear | Fatigue | Coughing | Angry/dry mouth | Breathing | Smell | Mucus/pain HN | ||

| Serbia | Dependents | Fear | Support | Swallowing | Depression | Spiritual | Regret/taste | Breathing | Chewing | |

| Sweden-S | Dry mouth | Fear | Mucus | Swallowing | Salivation | Chewing/mouth O | Dental | Cancer T | Fatigue | |

| Brazil | Fear | Dry mouth | Swallowing | Pain HN | Fatigue | Taste | Mucus | Coughing/shoulder | Anxiety/smell | |

| France | Fear | Dry mouth | Salivation | Pain HN | Chewing | Fatigue | Dental | Speech | Appetite | Anxiety/sleeping |

| Belgium | Fear | Dry mouth | Fatigue | Speech | Salivation | Chewing | Anxiety/pain HN | Appetite | Sleeping | |

| Sweden-U | Dry mouth | Fear/Mucus | Salivation | Taste | Dental health | Swallowing | Fatigue | Chewing | Cancer T | |

| Italy | Dry mouth | Fear/Mucus | Swallowing | Chewing/fatigue | Salivation | Dental | Pain HN | Speech | ||

| UK-S | Chewing/Fear | Depression/dry mouth | Sore mouth | Anxiety/salivation | Pain elsewhere/mouth O | Cancer T/energy levels/fatigue | ||||

| India-T | Cancer T | Dry mouth | Dental | Mouth O | Chewing | Speech/taste | Fear | Angry | Swallowing | |

| India-A | Chewing/fear/speech | Coughing | Mouth O | Mucus | Dry mouth | Pain HN | Anxiety | Swallowing/fatigue | ||

| Poland | Dry mouth | Speech | Coughing/mucus/swallowing | Fear | Taste | Weight | Breathing | Fear of adverse events/mood | ||

| Australia | Fear | Chewing | Dry mouth/speech | Dental | Fatigue/mouth O | Pain HN | Taste | Cancer T | ||

| Taiwan | Dental health | Chewing | Dry mouth | Swallowing | Salivation | Mouth O | Fatigue | Appearance | Speech | Fear |

| Germany | Fear | Chewing/dry mouth | Cancer T/fatigue | Dental | Swelling | Swallowing | Mouth O | Appetite/pain HN | ||

| Malaysia | Dry mouth | Fear | Chewing | Dental | Cancer T/mouth O | Fatigue/sleeping/shoulder/taste | ||||

| UK-L | Dry mouth | Fear | Chewing/fatigue/swallowing | Dental | Pain HN | Mouth O/mucus/sore mouth | ||||

- Note: Chewing, chewing/eating; Fear, fear of the cancer coming back; Fatigue, fatigue/tiredness; Dental, dental health/teeth; Speech, speech/voice/being understood; Pain HN, pain in the head and neck; Cancer T, cancer treatment; Mouth O, mouth opening; Wound H, wound healing; Regret, regret about treatment; Dependents, dependents/children; Support, support for my family; Spiritual, spiritual/religious aspects.

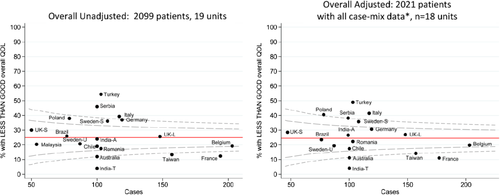

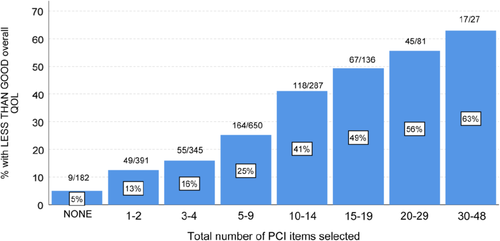

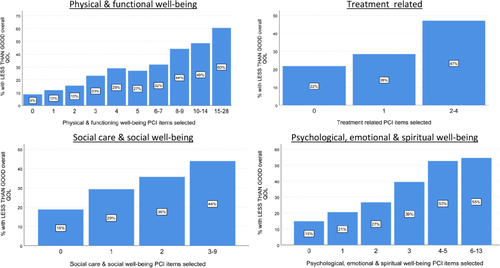

Overall, QOL was known for 2099 patients and was reported by 4% (94) of patients as “outstanding,” 30% (625) as “very good,” 41% (856) as “good,” 17% (362) as “fair,” 6% (123) as “poor,” and 2% (39) as “very poor,” Thus, overall QOL was less than good for 25% (524/2099) and Figure 6 presents funnel plots showing unit variation both before and after case-mix adjustment. Case-mix adjustment made little difference implying stronger systematic unit differences exist, though these differences were smaller than seen for numbers of PCI items selected. Binary regression assessed the association of each case-mix variable with the percentage of patients reporting less than good QOL after adjustment for other case-mix variables as independent predictors and for unit clustering (Table 5). The adjusted risk ratios suggest females were more likely to report less than good QOL, risk ratio 1.27, 95%CI: 1.05 to 1.53. There were also higher risk ratios observed for late tumor stage and use of radiotherapy/chemotherapy though confidence intervals about these risk ratios do include the possibility of no increased risk. Overall, these case-mix variables were less compelling as predictors of QOL than PCI predictors of QOL, as seen in the results from separate analyses using PCI scores as predictors in which a greater number of PCI items endorsed were associated with poorer QOL (Figure 7). Similar (though less striking) progressive associations were seen within each PCI domain (Figure 8).

| Patients with less than good overall QOL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw data | Risk ratioa unadjusted | Risk ratioa after adjustment | ||

| Sex | Men | 23% (338/1468) | Reference | |

| Women | 29% (185/630) | 1.28 (1.09-1.49) | 1.27 (1.05-1.53) | |

| Age at diagnosis | <55 | 25% (124/500) | Reference | |

| 55-64 | 25% I171/671) | 1.03 (0.84-1.26) | 1.01 (0.81-1.27) | |

| 65-74 | 22% (148/662) | 0.90 (0.73-1.11) | 0.92 (0.68-1.23) | |

| ≥75 | 31% (81/262) | 1.25 (0.98-1.58) | 1.26 (0.89-1.78) | |

| Stage | Early | 22% (203/938) | Reference | |

| Late | 28% (318/1144) | 1.28 (1.10-1.50) | 1.26 (0.94-1.68) | |

| Site | Oral | 27% (267/1003) | Reference | |

| Oropharynx | 26% (111/420) | 0.99 (0.82-1.20) | 0.91 (0.69-1.20) | |

| Larynx | 21% (85/414) | 0.77 (0.62-0.96) | 0.79 (0.57-1.09) | |

| Other | 23% (60/257) | 0.88 (0.69-1.12) | 0.85 (0.65-1.13) | |

| Treatment | Surgery only | 22% (164/743) | Reference | |

| RT±CT only | 26% (124/480) | 1.17 (0.96-1.43) | 1.17 (0.83-1.65) | |

| Surgery and RT±CT | 27% (233/864) | 1.22 (1.03-1.45) | 1.11 (0.77-1.61) | |

| Time from diagnosis | <12 months | 27% (150/551) | Reference | |

| 12-23 months | 29% (118/406) | 1.07 (0.87-1.31) | 1.09 (0.88-1.34) | |

| 24-59 months | 21% (129/612) | 0.77 (0.63-0.95) | 0.78 (0.60-1.02) | |

| ≥60 months | 24% (114/472) | 0.89 (0.72-1.09) | 0.93 (0.71-1.21) | |

- Abbreviation: QOL, quality of life.

- a Risk ratio (with 95% confidence interval) for unadjusted and then adjusted for other case-mix factors and for within-unit clustering (n = 2021 with QOL and all case-mix known).

Binary regression also assessed the association of each PCI item with less than good QOL, adjusting for unit clustering, and 38 of the 56 were significant at the P < .001 level and all but three (appetite, hearing, and carer) were significant at P < .05. All 56 had risk ratios over 1.00, with 55 over 1.30, median (IQR) risk ratios 1.75 (1.57-1.92) range 1.05 to 2.34. This again supports the number of items selected either overall or by domain being progressive indicators.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first time that an item prompt list such as the PCI has been used across such a diverse number of units in different healthcare settings. In routine clinical practice, it is feasible to use both the UW-QOLv4 and PCI in digital format with algorithms to identify immediately those patients doing badly and what issues they wish to talk about.11 However, in situations where digital systems for collecting patient reported outcomes are not used, a single sheet paper PCI is a way of alerting clinical teams as to which patients need additional support. A PCI approach in routine follow-up clinics could possibly result in a clinically meaningful and significant difference in QOL, emotional dysfunction, and distress at 1 year and is the subject of ongoing research.9 The primary outcome measure for this ongoing randomized trial is the percentage of patients reporting less than good overall QOL, hence the inclusion of the one item UW-QOLv4 question in our study. The PCI is a condition-specific prompt list and is different to other tools such as the Cancer Survivors' Survey of Needs (CSSN), and Cancer Survivors' Unmet Needs measure (CaSUN).16, 17

There are several limitations to this study. It was nonfunded with self-selecting units and with no attempt to obtain representation from every continent, nor within each country. The intention was for consecutive patients to be approached to reduce selection bias and although reports from collaborators suggest that relatively few patients declined it is a limitation of the study that no log was made of such patients and consequently the accrual rate for the study is unknown. Missing data in selected patients was minimal. Contributing units reported little difficulty in translating the PCI. Some words caused confusion such as “activity” and “regurgitation” and some items may not always have seemed applicable to some healthcare settings, such as having access to financial benefit support, nursing care at home and gastrostomy feeding tubes. Regarding the question of QOL, the term “outstanding” is extreme for some cultures, where “very good” is the best to be expected. In some cultures, it might be considered unacceptable to ask about certain topics such as intimacy and sex; however, using the PCI patients can choose not to identify certain issues and focus on other aspects. If the PCI is to be used more widely it would be appropriate to undertake further cross-cultural translation studies to help frame each item within the context of the individual healthcare setting, which would help determine the utility of using the item prompt list. The cohort were all first-time users of the PCI though in future a longitudinal study of PCI responses would help reveal any temporal differences in items within clinical settings. In terms of data analysis, we looked at variation between units by the case-mix factors used and future studies could include other aspects such as comorbidity, educational level, occupation, and carer support.

4.1 Patient concerns inventory

There are clear systematic differences between units in the number and type of items selected after case-mix adjustment. Some units chose more items across all domains. This is most likely to reflect cultural differences but possibly more pertinent are the expectations of patients as to what they want to talk about in their consultations and their expectations based on previous use of their local healthcare systems. It may reflect the way the PCI is framed in the clinical setting and also linguistic issues. Lack of access to information about cancer treatment, superstitious beliefs and illiteracy may also be contributory factors. There are likely to be differences between countries with developing healthcare systems and those with more resources to help rehabilitation and adaptation. Potentially, there are also differences in disclosure between countries in respect of doctor and patient communication, for example, a greater cultural willingness in general to disclose rather than to conceal problems and a higher generalized tendency to report symptoms. Inevitably, there will be cross-cultural differences in respect of family and care support and spiritual/existential aspects of having cancer. All these areas need further research involving qualitative methodology.

There were similarities to earlier smaller single unit reports regarding the most common items selected.12 Certain items were very common and impact across all patients in respect to their cancer treatment. “Dry mouth” was in the top five items selected for 17 of the 19 units and in the top 10 items selected for 18 units (Table 4) and “fear of the cancer returning” was in the top 10 selected items for all 19 units. It is appropriate to advocate treatments that minimize xerostomia as a side effect, such as the use of IMRT. Also, when balancing risks vs benefits consider withholding radiotherapy following surgery and saving that option for salvage.18 It is important to encourage patients to talk about these items as there are interventions available. Some are informal in the clinical consultation through recognition and empathy, others involve formal counseling strategies such as the AFTER intervention for fear of recurrence.19

4.2 Quality of life

Previous research found a relationship between number of symptoms, functional and physical status, and overall QOL.20 In our study, the adjustment for patient characteristics made little difference to unit variations in overall QOL. The number of PCI items appeared more strongly associated with overall QOL than the case-mix variables. Almost all of the PCI items were significantly predictive at the P < .05 level and all 56 had risk ratios over 1.00. This would imply that the count of just about any subset of PCI items selected will be progressively predictive of overall QOL; this is reflected in Figures 7 and 8 with increasing PCI domain item totals and with the total number of items being the most predictive.

The PCI approach facilitates tailored multidisciplinary team support within a holistic and individualized framework. Further research is required to assess how the PCI approach alters the consultation dynamic across different cultural and health care settings. There is a lack of PCI data from some countries (eg, USA and Mainland China) and so the next step is to construct representative patient profiles for each continent and to include additional case-mix factors. Also, there needs to be evidence on how the use of the PCI might lead to better QOL outcomes.9 Recognizing and sharing differences in patient experiences across health systems provides an opportunity to reflect on what we can learn from others and how we might best focus on areas for improvement.

5 CONCLUSION

Although there are similarities in the PCI between the 19 units, differences do exist and are larger than what would be expected by case-mix factors alone. It is likely that the PCI reflects subtle differences in priorities across cultures that need to be addressed in order to improve QOL outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The French ENT with Gettec French Group. (D Salvan in Paris, O Malard in Nantes, N Fakhry in Marseille, S Vergez in Toulouse, Ph Shultz in Strasbourg, C Righini in Grenoble, B Barry in Bichat Paris, N Bonmardion in Rouen, S Testelin in Amiens, and E Babin Caen). A notable acknowledgement to Pierre Demez at Liège, Belgium before his untimely demise.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.