Ethical and policy considerations for organ trafficking and transplant tourism: Based on the UK's first international case of human trafficking for the purpose of organ removal

Abstract

This study examines the UK's May 2023 judgment in an international organ trafficking and organ tourism case. Human trafficking for organ removal is one of the least understood but growing forms of trafficking worldwide. Countries in the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas are often widely criticized by the international transplant community as sites for organ trafficking. However, we believe that when discussing this issue, it is not just these areas that need to be addressed. What is particularly special is that this case not only involves transnational human trafficking, organ trafficking, and illegal organ transplantation interest chains but also involves the participation of national political officials and complex social and humanistic factors. This article focuses on the current ethical and policy issues involved in organ transplant tourism and organ trafficking and analyzes the implications of this case for our country's donation and transplantation work.

Abbreviation

-

- UK

-

- United Kingdom

1 INTRODUCTION

Trafficking in persons for the purpose of organ removal is one of the least understood but growing forms of trafficking worldwide [1]. Countries in the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas are often widely criticized as organ trafficking sites by the international transplant community. However, we must also consider other regions when discussing the issue of organ trafficking. All countries involved in organ transplant tourism worldwide have vulnerable populations that may be exploited; hence, they have the potential for illegal organ trade and may turn a blind eye to profit-making practices. Therefore, medical institutions in every country worldwide should pay due attention to the issue of organ trafficking to begin to address this global inequity.

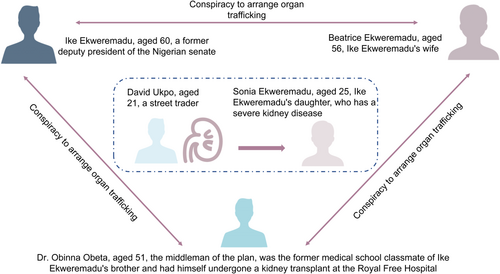

A recent international case of human trafficking for the purpose of obtaining organs has once again triggered a heated debate on organ trafficking in the international academic world. What is particularly special about this case is that it not only covers transnational human trafficking, organ trafficking, and illegal organ transplant interest chains, but also involves the participation of national political officials and complex social and human factors. On May 5, 2023, Ike Ekweremadu, a Nigerian senator and former deputy president of the Nigerian Senate [2], was sentenced to more than 9 years in a United Kingdom (UK) prison for his part in a conspiracy to trade on the “poverty, misery and despair” of vulnerable people, which is considered as a slavery and human trafficking offense under the 2015 UK Modern Slavery Act [3]. His wife and Dr. Obinna Obeta, who brokered the organ sale, were also convicted (Figure 1). The Ekweremadu case is the first in the UK to result in an organ trafficking conviction.

2 ETHICAL AND POLICY DISCUSSIONS

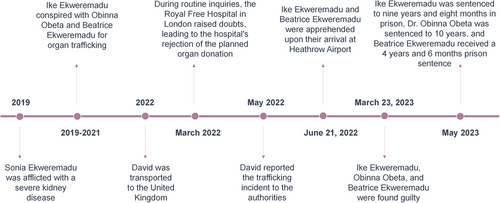

As defined by the United Nations [4], organ trafficking refers to the control of potential donors through the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, kidnaping, fraud, deception, abuse of power or position of weakness, or the giving or receiving of money or benefits for the purpose of obtaining organs, tissues, or cells for transplantation [5]. Although not all medical tourism that requires cross-border travel by organ transplant recipients or donors is organ trafficking, organ transplant tourism has connotations of organ trafficking [6]. The trafficked victim in this international case was a 21-year-old man who sold telephone parts for a living in Lagos, Nigeria [7]. The intended recipient of the organ was Ekweremadu's daughter, Sonia Ekweremadu, who had severe and worsening renal disease (Figure 2).

The UK government allowed living organ donation between relatives or acquaintances until 2004 but removed this restriction when the 2004 Human Tissue Act was enacted to allow organ donation for strangers. However, no payments were made to the recipient or donor. In 2008, the Declaration of Istanbul on organ trafficking and transplant tourism was developed at the Istanbul Summit on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism in Istanbul to provide guidelines to prevent the commercialization of organ transplant services using the poor and vulnerable as sources of organs for the rich [5]. The Declaration of Istanbul Custodian Group was established to follow up the achievements and progress in meeting the Declaration of Istanbul's goals.

In 2018, the Declaration of Istanbul Custodian Group updated the Declaration of Istanbul to encompass organ trafficking and transplant tourism, stating that “trafficking in human organs and trafficking for the purpose of removing organs should be prohibited and criminalized.” In addition, the Group emphasized that “health professionals and healthcare institutions should assist in preventing and addressing organ trafficking, trafficking in persons for the purpose of organ removal, and transplant tourism.” [8] In the Ekweremadu case, the relevant personnel at the Royal Free Hospital in London played a key role in terminating the case for organ procurement. The defendant tried to persuade the Royal Free Hospital medical staff to consider the trafficked person as Sonia Ekweremadu's cousin to facilitate the organ donation. However, Dr. Peter Dupont, a consultant at the Royal Free Hospital, raised questions after learning that the proposed donor was unaware of the organ transplant procedure and lacked the required life-long health insurance. Dr. Dupont consequently deemed the individual ineligible for organ donation, which led to the suspension of organ procurement and transplantation procedures [9].

Economic exploitation and physical mutilation often occur during the process of organ trafficking and organ transplant tourism. Although countries around the world have basically achieved consensus in strictly prohibiting the sale of human organs and advocating for voluntary, unpaid donations to increase the supply of organs for transplantation, the demand for organs available for transplantation is far higher than the supply; therefore, the organ black market is still thriving worldwide. It has been estimated that up to 10% of kidney transplants worldwide involve organ trafficking [10]. The illegal trade in organ trafficking considers the human body and its parts as commodities. Regardless of the behavior or method of providing or giving economic incentives or paying money for organ transplantation, organ trafficking violates respect for human beings in addition to basic ethical values. Thus, trafficking for the purpose of obtaining human organs leads to wider exploitation of vulnerable groups and global social problems.

It is particularly important to note that for all organ or human trafficking crimes, the consent of the trafficked person cannot be considered as an ethically and legally defensible reason for the crime. In this case, whether the trafficking victim knew about the transnational organ sale was irrelevant to the conviction and sentencing of Dr. Obeta and the Ekweremadu. From an ethical perspective or legal principles, individuals do not have the right to allow other people to exploit them and trade their bodies and organs. This behavior is based on the exploitation of poor and vulnerable groups at the cost of selling human dignity and intrinsic value; therefore, it is not ethically defensible or acceptable for society as a whole [11].

Over the years, international organizations and many countries have formulated guidelines and the corresponding laws and regulations based on bioethical principles to prohibit commercial organ transplants and trafficking, which have been implemented to a certain extent. However, the problem of organ trafficking persists and there is still much room for improvement. The continued increase in the number of illegal organ transplants can be attributed to ineffective legislation, weak enforcement, and the lure of large profits [12]. However, the mere enacting of laws and inconsiderate policy actions often have limitations, operational defects, cannot fundamentally solve the problem, and may also bring more negative risks [13]. For example, a study of efforts to ban illicit organ trade from a criminological perspective suggests that legal bans do not necessarily eliminate the problem and reduce illegal activity [14]. Instead, they potentially shift criminal activity to other areas, which drives underground trade and leads to higher crime and victimization rates [13, 15]. Therefore, the feasibility and effectiveness of both international and domestic policies and interventions should be considered fully.

In addition, more attention should be paid to the special role and potential influence of medical professionals in this issue. Some researchers suggest that organ trafficking cannot occur without the involvement of medical professionals [13]. The prohibition of acts that include mediation or other facilitation of organ trafficking, including for medical purposes, is also emphasized in the Declaration of Istanbul. In addition, health professionals and health-care facilities should help to prevent and address these problems.

The problems of organ trafficking and commercial organ transplants cannot be solved by relying only on a single country's legislation or law enforcement. Successful enforcement may help crack down on the visible part of the iceberg of organ trafficking networks, but it will not fundamentally affect crime rates [13]. All governments should consider more comprehensive and adequate programs to address these challenges, which are not limited to incentives for cadaver organ donation but should also include phased reflections on intervention policies or strategies, exploring targeted substantial issues, promoting broader public participation and discussion, providing diversified education, and promoting scientific and technological research progress to prevent organ trafficking activities. Otherwise, the problem will persist and may be exacerbated in various disguised ways.

3 CONCLUSION

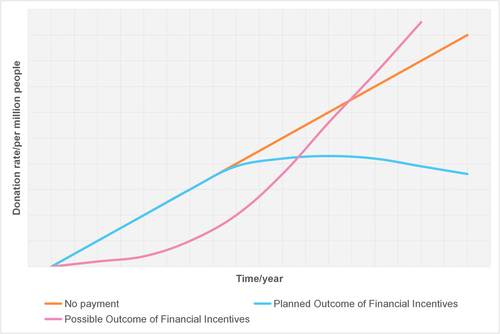

This case provides a resource for the work of organ donation and transplants in China. First, informed consent is a necessary condition but is not sufficient. During the process of providing informed consent for living organ donation, it is not only necessary to obtain the donor's consent, but also to assess the extent of any possible harm to human beings. Second, any incentive policy for organ donations must undergo ethical assessments. Due to cognitive limitations in addition to the influence or limitations of other factors in the social environment, policies cannot be considered comprehensive when introduced. However, policies can be improved gradually to solve emergent problems and close any loopholes. Especially considering intervention strategies to increase the rate of organ donation, financial incentives or disguised economic incentives cannot be defended ethically. Prof. Alexander Capron illustrated three relationships between donation rates and incentive policies (Figure 3): that is, no financial incentives, planned financial incentives, and the possible outcomes of financial incentives. According to Prof. Capron, under the model without financial incentives, the donation rate may increase very slowly at the beginning and be lower than the expected or actual results of economic incentives. However, as the public has accepted the need for organ donation and transplants over time, donation rates have increased rapidly after several years to exceed the expected and actual results of economic incentives. Nevertheless, the incentive for organ donation from corpses has always been a concerning issue. The discussion and research of ethical issues are particularly important for the healthy and sustainable development of organ donation and transplants in China as a responsible country that provides organ transplants. Third, conscientious personnel involved in the field of organ donation and transplants should remain acutely attuned to the potential occurrence of organ trafficking and clandestine organ trade activities, with particular emphasis on the context of living organ procurement and transplantation. Implemented in 2007, the Human Organ Transplantation Regulation stipulates that “the recipients of living organs are limited to the spouses, immediate blood relatives or collateral blood relatives within three generations of living organ donors, or those who have evidence to prove that they have formed a kinship relationship with living organ donors through assistance.” On this basis, the Chinese Ministry of Health's 2013 regulation for the standardization of living organ transplantation further stipulates that “living organ donors and recipients are limited to the following relationships: only spouses who have been married for more than 3 years or have children after marriage; direct blood relatives or collateral blood relatives within three generations; and only between adoptive parents and their children, and between stepparents and their stepchildren.” In the realm of organ donation and transplants, the strong professionalism required by this work indicates that the cooperation of all medical personnel is very important. Every responsible doctor and related professional should be highly alert to the possibility of commercial organ trafficking behavior, and take prompt and responsible action when organ donors are found to lack genuine informed consent or evidence of a biological relationship is questionable.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Xiaomei Zhai. Writing—original draft: Lanyi Yu. Writing—review & editing: Lanyi Yu and Xiaomei Zhai. Supervision: Xiaomei Zhai.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study received no funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

INFORMED CONSENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.