Teacher educational qualifications and the quality of teacher–student interactions in senior high school classrooms in Ghana: Could teacher self-efficacy bridge the qualifications gap?

Abstract

Teacher qualifications, self-efficacy, and quality of teacher–student interactions (QTSIs) are critical factors in educational discourse. While research shows varied results for each variable, studies have yet to examine all three variables simultaneously. To what extent does teacher self-efficacy contribute to bridging the qualifications gap toward QTSIs? This study investigates the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs and the potential role of teacher self-efficacy in addressing the qualifications gap. An empirical analysis of 419 valid responses from senior high school (SHS) teachers in Ghana utilizing the t-test and ordinary least squares estimators uncovered noteworthy findings. The study revealed a positive influence of teacher educational qualifications on QTSIs, with higher qualifications (master's degree) significantly enhancing QTSIs compared to lower qualifications (bachelor's degree). Teacher self-efficacy positively moderated the impact of teacher educational qualifications on QTSIs. The study also revealed that while higher teacher self-efficacy was beneficial in bridging the educational qualifications gap between bachelor's and master's degrees on QTSIs, it only partially bridged the gap. This study's findings invite policymakers, teacher educators, and school authorities to employ a balanced approach to improving QTSIs in SHS classrooms in Ghana by encouraging teachers to advance their qualifications and creating an enabling environment to develop their self-efficacy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Teachers engage in various forms of classroom practices, including student engagement, emotional support, instructional strategies, and classroom management (Kohake et al., 2023). Research has shown that the quality of teacher–student interactions (QTSIs) in the classroom positively relates to successful curriculum implementation (Xiao et al., 2023). QTSIs create a positive classroom climate and promote teachers' performance and students' engagement, adaptation, and performance (Pianta et al., 2012a). Continuous reports of unimpressive QTSIs at senior high schools (SHSs) in Ghana have generated a compelling argument to identify and understand factors that influence the QTSIs at SHSs in Ghana (Kwarteng, 2018; Ministry of Education, 2017).

In improving QTSIs, the qualifications of teachers hold significant importance (Hanushek & Rivkin, 2006; Sancassani, 2023). For example, goal 4.c of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) explicitly targets a substantial increase of qualified teachers in developing countries by 2030 (UNESCO, 2021). Countries have specific qualifications for teachers at every level of education (Ghana Education Service, 2019; National Center for Education Statistics, 2018). Ghana is no exception. For instance, in Ghana, the minimum qualification to teach in SHSs is bachelor's degree in education in a specific subject area or equivalent with a postgraduate diploma in education (Buabeng et al., 2020; Ghana Education Service, 2019). Within the classroom setting, teachers with higher educational qualifications are expected to promote QTSIs (Hanushek & Rivkin, 2006) since they are exposed to advanced content and pedagogy, which equips them with advanced knowledge and skills to enhance their pedagogical practices (Sancassani, 2023). Over the years, the government of Ghana, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, has introduced policies and reforms, including the creation of the National Teacher Council, National Teachers' Standards, and Transforming Teacher Education and Learning to establish professional and ethical standards for teachers and teaching, and improving the quality of teaching and learning (Buabeng et al., 2020; Ministry of Education, 2017). Despite these efforts, achieving QTSIs in SHSs remains challenging (Kwarteng, 2018).

In the phase of challenges in achieving desired educational outcomes, teacher self-efficacy may play a critical role. Teacher self-efficacy, the belief in a teacher's capability to execute a task, fosters resilience and tenacity to attain desired outcomes (Bandura, 1977, 1986; Heng & Chu, 2023). Teachers with higher self-efficacy are more likely to manage the classroom effectively, show higher instructional quality, use more differentiated instruction and constructivist approaches, develop challenging lessons, use classroom management and instructional methods to encourage student autonomy, and keep students on task (Brenner, 2022; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007). Specifically, Zhang and Ye (2023) noted that teacher self-efficacy can ignite teacher enthusiasm to achieve results. Therefore, teacher self-efficacy could play a role in achieving QTSIs in the classroom.

Despite research on teacher self-efficacy, qualification, and educational outcomes, a literature review revealed the following limitations. Firstly, while there are studies on teacher educational qualifications and educational outcomes in general, the literature on teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs is limited. Most studies focused on teacher educational qualifications, student performance (Goldhaber & Brewer, 1997), and educational outcomes (Mugoya et al., 2022) with little emphasis on QTSIs. Secondly, studies have not examined all three variables simultaneously, making the role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship unexplored. Thirdly, it is still being determined whether highly educated teachers with low self-efficacy or teachers with low educational qualifications and high self-efficacy will positively impact classroom interactions. Finally, a critical literature review could not reveal whether teacher self-efficacy could fill the qualifications gap between bachelor's and master's degree teachers to improve QTSIs. This study is built on the gaps above in the literature to investigate whether teacher self-efficacy could bridge the qualification gap.

The objective is divided into three. Firstly, it examines teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs relationship, assessing how different qualification levels promote QTSIs. Secondly, it explores the moderating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs. Lastly, it decomposes teacher self-efficacy into different levels to determine how these levels influence teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs.

The study makes the following novel contributions to the literature: This research linked teacher educational qualifications to QTSIs in the classroom, a relationship that is missing in the literature. Unlike previous studies that introduced teacher educational qualifications as one composite variable in educational research (Hanushek & Rivkin, 2006), this study decomposed the variable into different levels of qualifications and explored their unique impacts on QTSIs. Furthermore, the study introduced teacher self-efficacy in the qualifications–QTSIs relationship to innovatively explore how teachers' beliefs in their capabilities influence the relationship between their educational qualifications and QTSIs, shedding light on the complex dynamics underlying the qualifications–QTSIs relationship. Thus, this study expands our understanding of the qualifications–QTSIs relationship and offers a comprehensive framework, incorporating human capital theory, self-efficacy theory, and social cognitive theory to explore the underlying mechanisms and dynamics involved. Finally, it decomposed the teacher self-efficacy into different levels to determine the extent to which these levels influence qualification–QTSIs relationships, focusing on whether high self-efficacy levels can bridge the qualifications gap (i.e., the educational gap between bachelor's and master's degrees). This novel approach provides valuable insights into the nuanced impact of different self-efficacy levels on the qualifications–QTSIs relationship. It offers a deeper understanding of how teacher beliefs can bridge the gap between different educational qualifications in promoting QTSIs for successful teaching and learning.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS

2.1 Teacher educational qualifications

Teacher educational qualification is a term that refers to the academic and professional credentials that a teacher must possess to teach in a specific level or subject. After a comprehensive review of teacher qualifications across multiple countries, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics defined a qualified teacher as one with “at least the minimum academic qualifications required for teaching their subjects at the relevant level in a given country in a given academic year” (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2023, p. 1). In Ghana, the minimum qualification for teaching at the SHSs is a bachelor's degree in mathematics education (Ghana Education Service, 2019). This is typically a 4-year bachelor's program covering content knowledge, teaching methods, classroom management, education policy, and internships (National Teaching Council, 2018). Many high school teachers have majors in their subject area and teacher training. In addition, Ghana has a National Teachers' Standards framework defining expectations regarding professional knowledge, instructional practice, teacher ethics, additional roles, and assessment. Teachers must show evidence of meeting these standards through performance evaluations (National Teaching Council, 2018). Nevertheless, teachers with bachelor's or master's degrees, not specifically in education, must acquire a postgraduate diploma in education to fulfill the minimum educational qualification for teaching mathematics in SHSs (Ghana Education Service, 2019).

The importance of teacher educational qualification is recognized globally. This is evident through the inclusion of goal 4.c in the SDGs, which specifically targets the substantial increase of qualified teachers in developing countries by 2030 (UNESCO, 2021). Although the country faces an inadequate supply of trained and qualified teachers, especially in rural areas, Ghana is committed to achieving goal 4.c (Amoah et al., 2020). As a result, investigating teacher educational qualifications within the Ghanaian context is paramount.

2.2 Quality of teacher-student interactions

According to Pianta and Hamre (2009), QTSIs can be described in terms of emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support. Emotional support encompasses behaviors such as expressing positive emotions, warmth, and responsiveness toward students, as well as teachers' attentiveness to students' needs and their incorporation of students' perspectives (Pianta et al., 2008). On the other hand, classroom organization refers to teachers' proactive use of strategies to establish routines, promote productivity, and actively engage students, as well as students' adherence to expectations (Pianta et al., 2008). Instructional support pertains to the provision of personalized feedback, scaffolding, opportunities for rich language exposure, and activities that foster higher-order thinking skills (Hamre & Pianta, 2010).

The QTSIs are a core component of effective teaching and learning (Hofkens et al., 2023). High QTSIs have meaningful links to students' learning and mental health and foster the development of students' academic and social-emotional skills (Doyle et al., 2022). According to Pianta and Allen (2008), the QTSIs play a crucial role in fostering student engagement and effort, promoting knowledge and thinking, developing problem-solving and communication skills, and nurturing positive relationships with others. Therefore, improving the QTSI is crucial for initiatives aimed at creating and supporting effective learning environments on a large scale in the educational context (Hofkens et al., 2023). In the context of Ghana, literature highlight tensions in components of teacher–student interactions such as students' discipline and teacher–student dependency in the instructional process at the high school level (Baafi, 2020; Mensah & Koomson, 2020). For instance, Baafi (2020) observed that teachers felt that students depleted their energy and were often disruptive, complaining about trivial issues, thereby affecting the quality of interactions teachers had with their students.

2.3 Teacher self-efficacy

Teacher self-efficacy refers to a teacher's belief in their capability to effectively engage in and carry out the necessary actions to achieve a task at a certain level of competence within a specific context (Dellinger et al., 2008). Typically, teacher self-efficacy encompasses various aspects, including instructional practices, assessment methods, and classroom and school discipline strategies. Teaching self-efficacy is the motivational concept used to describe the beliefs one holds about one's ability to accomplish a specific teaching task (Bandura, 1977; Twohill et al., 2023). The level of teaching efficacy impacts various aspects of a teacher's approach to planning and delivering lessons, including their beliefs about student capabilities, instructional practices, classroom demeanor, persistence, and ability to recover from setbacks (Holzberger et al., 2013; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). Teachers with high teaching efficacy exhibit confidence in their student's learning abilities and demonstrate more remarkable persistence (Hourigan & Leavy, 2022). They are also more inclined to take risks, employ inquiry-based and student-centered teaching strategies, and maintain a strong academic focus in the classroom (Hourigan & Leavy, 2022).

On the other hand, teachers with lower teaching efficacy tend to believe that students are incapable of learning, and in finding reasons to justify this assumption, they overly rely on teacher centered pedagogies (Allinder, 1994; Holzberger et al., 2013) which largely deny active students engagement in the lesson. Consequently, it is suggested that enhancing teaching efficacy can foster increased persistence and confidence in adopting innovative and student centered teaching practices (Depaepe & König, 2018). Furthermore, teaching efficacy influences teacher's achievement (Segarra & Julià, 2022). Studies have shown that teaching efficacy primarily emerges during the initial stages of teacher education, and once it is established, it tends to remain stable and many will be resistant to change (Ekstam et al., 2017).

2.4 Teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs

The role of teacher educational qualifications in educational outcomes continues to attract research across the world, especially in developing countries. From the theoretical perspective, the Human Capital Theory explains the gains of education and training as a form of investment in human resources aiming at improved performance (Belay et al., 2021; Nafukho et al., 2004). A teacher's human capital consists of his/her content and pedagogical knowledge and demonstrating emotional and social capabilities to support students from various backgrounds (Belay et al., 2021; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012). The human capital theory suggests that education increases the productivity and efficiency of workers such that teachers with higher qualifications (i.e., advanced degrees or specialized training) have more human capital in the form of knowledge, skills, and abilities, resulting in more effective teaching and better student outcomes (Belay et al., 2021). Notwithstanding, there are mixed outcomes from empirical literature, with some studies supporting the argument put forward by the human capital theory while others reject the proposition.

On the one hand, some studies found no significant or, in some cases, a negative association between teachers' degree attainment and educational outcomes. Buddin and Zamarro (2009) utilized longitudinal data spanning from 2000 to 2004 in California to examine the influence of advanced degrees held by classroom teachers on elementary-level student achievement in mathematics and reading. An empirical analysis using fixed effects regressions showed no significant impact on student achievement due to teacher educational qualifications. Similar findings were established by Shuls and Trivitt (2015) in Arkansas and Taiwan, respectively. An analysis of these studies revealed that the lack of association between teacher educational qualifications and students' outcomes could be attributed to how educational qualifications are measured among the authors and contextual factors. For instance, Buddin and Zamarro (2009) used teacher licensure, while Shuls and Trivitt (2015) included, among other variables, qualification route, graduate degree, and experience. All these ways of measuring teacher educational qualifications do eliminate teacher subject-specific qualifications that influence educational outcomes. Sancassani (2023) argues that the importance of teacher subject-specific qualifications in educational settings must be considered.

On the other hand, some studies have revealed a positive relationship between teachers' educational qualifications and educational outcomes (Goldhaber & Brewer, 1997; Mugoya et al., 2022). For instance, Goldhaber and Brewer (1997) revealed that teacher educational qualifications have a significant influence on 10th-grade mathematics test scores. Similarly, Mugoya et al. (2022) examined how teachers' qualifications impact the teaching and learning of history in senior 4 of Kajara County, Uganda. Teachers with explicit history instruction involved learners in history lesson activities effectively. In Ghana, Owusu and Yiboe's (2013) analysis of data from 21 SHS French teachers from Ghana's Western Region revealed a positive influence of teacher qualification on curriculum implementation. While these studies offer insights into teacher qualifications and educational outcomes, they lacked school-level and specific control variables that could affect the results. Ladd and Sorensen (2015) pointed out that when the estimation is without control variables, the effect of teacher's higher educational qualifications significantly influences the achievement of students. However, when school-level and student-specific control variables are introduced in the model, the effect disappears (Ladd & Sorensen, 2015). Considering that several factors influence educational outcomes, the exclusion of control variables could lead to omitted bias problems and unreliable estimates. This is not to say that these studies' outcomes are not relevant but instead call for more research that will incorporate proper controls. Furthermore, the literature review so far shows that none of these studies focused on the link between teacher educational qualifications and QTSI, leaving this area of research underexplored. Based on human capital theory propositions and the empirical literature reviewed, this study hypothesizes that:

H 1.Teacher educational qualifications will have a significant and positive influence on QTSIs such that the impact is more substantial when qualification is higher (i.e., a master's degree).

2.5 The role of teacher self-efficacy

Since the introduction of self-efficacy, a psychological construct within social cognitive theory and a central focus of self-efficacy theory, the role of teacher self-efficacy in educational outcomes has been widely researched (Bandura, 1977, 1986; Zhang & Ye, 2023). Teacher self-efficacy could play several roles in educational outcomes. However, many studies on teacher self-efficacy focused on its direct causal or mediation effect on educational outcomes. For instance, Hidayah et al. (2023) conducted a quantitative meta-analysis approach of 40 teacher self-efficacy studies published between 2014 and 2023. The authors revealed that while several methodologies have been employed to study teacher self-efficacy, almost all the studies treated teacher self-efficacy as a direct or mediating variable without considering its other roles in educational outcomes (Hidayah et al., 2023).

A few studies examined the moderating role of self-efficacy but outside the classroom context. For example, Gelaidan et al. (2023) explored the moderating role of creative self-efficacy of servant and authentic leadership as drivers of innovative work behavior. The results from structural equation modeling show that creative self-efficacy plays a moderating role in the relationship between servant and authentic leadership. The authors only concentrated on the employees in the Qatari public sector, making their findings less applicable to the education sector. Within the education sector, Parmaksız (2022) examines the relationship between phubbing frequency and academic procrastination tendencies of students and the effect of academic self-efficacy on this relationship. The study found that academic self-efficacy demonstrated a moderating influence by mitigating the detrimental consequences associated with phubbing, a behavioral problem, and the inclination toward academic procrastination. Considering the participants of the study, the finding applies to students but not teachers. Besides, although Parmaksiz's study applies to the education sector, it is not applicable in classroom settings or teacher–student interactions. Thus, moderating roles of teacher self-efficacy remain unexplored within the classroom settings.

The limited attention on the moderating role of teacher self-efficacy in classroom settings could be detrimental to QTSIs. Teachers may enter the classroom with high levels of education and competency, but classroom situations or challenges could pose a threat to how the teacher performs (Glassow et al., 2023). It takes a teacher with a high efficacy level to overlook these challenges and deliver as expected (Glassow et al., 2023). In the context of teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs, teacher self-efficacy may influence how teachers with different qualifications engage with their students in the classroom. Therefore, exploring the moderating roles of teachers' efficacy in teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs, especially in the Ghanaian context, where literature on teacher self-efficacy is evolving, is critical. In line with the literature and social cognitive and self-efficacy theoretical arguments, this study hypothesizes that:

H 2.Teacher self-efficacy will positively moderate the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs.

H 3.A higher teacher self-efficacy will have a stronger moderating effect on the relationship between bachelor's degree educational qualification and QTSIs than a lower teacher self-efficacy, such that the marginal effect approaches that of a master's degree qualification.

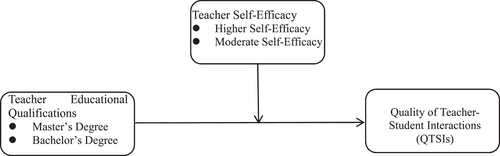

Figure 1 illustrates the study's framework. This framework posits that teacher educational qualifications (master's and bachelor's degrees) have a direct influence on QTSIs. This association is based on empirical research (Belay et al., 2021; Goldhaber & Brewer, 1997; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012) and human capital theory, which states that higher education increases an individual's production and worth. Advanced degrees are expected to offer teachers more significant subject matter expertise, more vital instructional abilities, and improved performance (Belay et al., 2021). These expanded capabilities gained through higher education are expected to transfer into higher-quality interactions with students, hence enhancing QTSIs.

Conceptual framework.

The framework further includes teacher self-efficacy as a moderating variable in qualification–QTSIs relationships, drawing on empirical research (Gelaidan et al., 2023; Parmaksız, 2022) and social cognitive and self-efficacy theories. This moderating effect implies that the impact of educational qualifications on QTSIs varies according to a teacher's degree of self-efficacy or belief in their capacity to instruct and engage with pupils successfully. Teachers with high self-efficacy might more effectively apply the knowledge and skills gained from their educational qualifications, thereby enhancing the qualifications–QTSIs. Those with low self-efficacy may need help to effectively utilize their educational expertise in student interactions, thereby weakening this relationship. This approach emphasizes the complicated relationship between educational qualifications, teacher self-efficacy, and QTSIs.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Participants and data collection

Surveys were used to collect data from SHS teachers in Ghana from March 13 to 11 April 2023. The continuous unimpressive nature of curriculum implementation in SHSs in Ghana (Kwarteng, 2018; Yidana & Ntarmah, 2016) and the limited exploration of teacher self-efficacy in Ghana make the context a good starting point to explore this topic. The concentration on teachers is critical because teachers are the best at judging their self-efficacy in executing the task (Bandura, 1977, 1986). This study took a keen interest in the consequences of attrition effects in the samples on research results. Therefore, we followed the recommendations for dealing with attrition effects by scholars such as Chatterjee and Hadi (2015) and Sprent and Smeeton (2016). According to scholars, a variable-to-sample ratio where 10 respondents are assigned to a single item on the questionnaire should be the minimum sample size to be used (Chatterjee & Hadi, 2015; Sprent & Smeeton, 2016). This approach is widely accepted and has proven to be useful in many studies (Quansah et al., 2023). This study has 30 items on the questionnaire for the respondents to answer. Therefore, the minimum sample size for this study should be 300 respondents, which is below the attrition effects that may be encountered. Through the heads of departments, 500 copies of the questionnaire were distributed to the teachers. This approach of increasing sample size to mitigate attrition effects and the effect of non-response bias is highly recommended in previous studies (Quansah et al., 2023). Out of the 500, 457 copies were retrieved. After the initial screening, 38 copies of the retrieved questionnaires were rejected because they either needed to be completed or had double responses for one or more items. Thus, 419 valid responses were used for the analysis. Since 419 is far more than the minimum 300 respondents' sample size, we can confidently conclude that the sample is large enough to mitigate attrition differences. Furthermore, the most current Ghana Education sector report revealed that there are 207,972 secondary school teachers at the SHS level (GCB Bank, 2023; Ghana Investment Promotion Center, 2022). At a 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error, the recommended sample size for this population (207,972) or more is 384 (Singh & Masuku, 2014; The Research Advisors, 2006), indicating that our sample size of 419 is representative of the population.

Teachers who participated in the study did so voluntarily. Teachers received clear information regarding the study's objectives and procedures. Their voluntary participation, giving them the freedom to decline or withdraw their agreement at any point without facing any negative consequences, was also emphasized. The participants were assured of their confidentiality and anonymity. Additionally, these details were explicitly outlined in the questionnaire. The heads or assistant heads (in authority at the time) of the participating schools, in collaboration with the school management, approved the protocol before collecting the data.

3.2 Variables and measures

The study's main variables are the QTSIs, the dependent variable; teacher educational qualifications, the independent variable; and teacher self-efficacy, the moderating variable. However, the research controlled for key demographic variables, such as age, sex, school location (SL), school category (SC), and years of experience, to minimize omitted variable biases and improve statistical accuracy (Goldhaber & Brewer, 1997; Malmberg et al., 2010).

3.3 Quality of teacher-student interactions

This study used Pianta et al.’s (2012a) 12-item Classroom Assessment Scoring System-Secondary (CLASS-S), a widely used instrument that assesses QTSIs in the classroom (Westergård et al., 2019). The CLASS-S measures QTSIs focusing on positive climate, regard for adolescent perspectives, teacher sensitivity, negative climate (reversed for analysis), behavior management, productivity, instructional learning formats, instructional dialog, quality of feedback, content understanding, student engagement, and analysis and inquiry. These items were scored on a 7-point scale (low to high), with higher scores indicating high QTSIs and low scores indicating otherwise. The scale has an initial adequate inter-rater agreement (0.78–0.96) and internal consistency (0.76–0.90) (Pianta et al., 2012a) with many other authors reporting similar reliabilities, validity, and applicability to different contexts and secondary levels (Kohake et al., 2023; Pianta et al., 2012b). This study's pilot test yielded a reliable Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.89, indicating the instrument's reliability within the Ghanaian context. The CLASS-S instrument demonstrates strong validity across multiple dimensions. Its content validity is demonstrated by a full covering of key teacher–student interaction aspects (Hamre et al., 2013). Construct validity is reinforced by confirmatory factor analyses, which validate the instrument's measures and their links to student outcomes (Allen et al., 2013; Pianta et al., 2012b). The scale's criterion-related validity is demonstrated by its capacity to predict changes in student achievement and behavioral engagement (Allen et al., 2013; Hafen et al., 2015). Research indicates that the instrument has cross-cultural validity (Kohake et al., 2023; Westergård et al., 2019), making it applicable in a variety of situations.

3.4 Teacher self-efficacy

The study measured teacher self-efficacy using the 12-item Teacher Sense of Efficacy scale developed by Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001). The Teacher Sense of Efficacy scale is widely recommended and used to measure teacher self-efficacy in various aspects of their teaching practice (Zhang & Ye, 2023). Some of the items include "To what extent can you provide an alternative explanation, for example, when students are confused? How much can you do to control disruptive behavior in the classroom? and How much you can do to motivate students who show low interest in school work?" Teachers rated their agreement with each statement on a 9-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (nothing) to 9 (a very great deal). A review of the literature reveals reliability between 0.70 and 0.96 (Yidana & Ntarmah, 2016; Zhang & Ye, 2023). This study's pilot results further confirmed the reliability of the instruments within the Ghanaian context at a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.86. Content validity is supported by the scale's comprehensive coverage of key aspects of teaching efficacy, including instructional strategies, classroom management, and student engagement (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). Construct validity is evidenced by factor analyses confirming the three-factor structure (instructional strategies, classroom management, and student engagement) of the scale (Klassen et al., 2009). Both criterion-related and cross-cultural validity of the scales have been with studies in diverse contexts supporting its psychometric properties (e.g., Fives & Buehl, 2009; Klassen et al., 2009). Discriminant validity is demonstrated by its ability to distinguish between teachers with varying levels of experience and across different subject areas (see Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007).

3.5 Teacher educational qualifications

In this study, teachers' educational qualifications were measured in terms of the level of education (e.g., bachelor's and master's) of the teachers, which is a common practice in educational research (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). This form of measurement also recognizes that teachers with different levels of education may possess different knowledge, skills, and abilities that could influence their teaching practices and impact the educational outcomes of students (Clotfelter et al., 2006; National Center for Education Statistics, 2019).

3.6 Common method bias

The study employed questionnaires to collect data from SHS teachers. While the questionnaires are proven to be reliable, scholars such as Podsakoff et al. (2003) and Jordan and Troth (2020) have shown that they can generate common method biases. As a result, this study followed these recommended steps to mitigate any potential variance/bias. First, the study used existing valid and reliable instruments proven in the literature. Besides, the items on these instruments were straightforward to understand, so participants did not have any issues responding to the questionnaires. In addition, we ensured participants' confidentiality and ensured that no single item on the questionnaires, including demographic information, could leave a trace of participants' identity. Finally, we used Harman's single-factor test as a statistical technique to verify the effectiveness of the methods to mitigate biases. The Harman's single-factor results showed that all single components accounted for less than 50% of the total variance explained. Specifically, the highest single factor explained just 23.18% of the variance explained, suggesting that common method biases are not an issue in this study.

3.7 Analytical procedure

A preliminary analysis such as frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, cross-tabulation, correlation, multicollinearity tests, validity, and reliability was carried out to provide insights into the accuracy of the data and verify if it meets the assumptions of the regression analysis (Field, 2013; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). The primary analysis was conducted on three levels using the t-test, and Ordinary Least Squares estimators were used to perform this analysis. Firstly, the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs was analyzed. Secondly, the moderating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs was estimated. Finally, the teacher self-efficacy was decomposed into different levels (high and moderate) to determine the extent to which these levels influence teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs with a focus on whether high efficacy levels could bridge the qualification gap. This procedure can be represented mathematically for a clear understanding of the relationships and estimations.

and , respectively represent teachers with master's degree and master's degree teachers' efficacy and the interaction term is given as . Similarly, and , respectively represent teachers with bachelor's degree and bachelor's degree teachers' efficacy, while the interaction term is represented as .

BMoTEL and BHTEL represent bachelor's degree teachers with a moderate efficacy level and bachelor's degree teachers with a high efficacy level, respectively. Their interaction terms with BEdu are represented as BEdu*BMoTEL and BEdu*BHTEL. Thus, Equations (6) and (7) help to establish the extent to which different efficacy levels among bachelor's degree teachers could help bridge the educational qualifications gap between bachelor's and master's degree teachers in terms of achieving QTSIs. If the coefficients of the bachelor's degree interactions terms (β3 in Equations (6) and (7)) approach the coefficients of the master's degree interaction term (β3 in Equation (4)), a statistical inference can be made that teacher self-efficacy has the potential of bridging the qualifications gap (Buis, 2017; Leeper, 2017). Equations (6) and (7) align with the study's conceptual framework with the inclusion of control variables.

4 RESULTS

According to Table 1 below, 247(58.95%) of the participants were males, and 172(41.05%) were females, suggesting male dominance in this study. The majority of the participants, 259(61.81%), were from Southern Ghana, while 160(38.19%) were from the Northern part of the country. This is not surprising since there are more SHSs in the Southern part than in the Northern part (Ghana Education Service, 2023). Most of the teachers involved in this study were from category B schools, followed by categories C and A, respectively. SHSs in Ghana are classified as A, B, and C, with category A schools being the highest ranked, followed by categories B and C (Amponsah et al., 2022). In terms of ages of teachers, the majority, 178(40.57%), were between 30 and 39 years, while 90(21.48%) were aged 40 years and above. Finally, the majority 179(42.72%) of the teachers had 1–5 years of teaching experience, while only 2.39% had more than 20 years of experience. Overall, most teachers have over 5 years of teaching experience.

| Variable | N | % | Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | School location | ||||

| Male | 247 | 58.95 | Southern Ghana | 259 | 61.81 |

| Female | 172 | 41.05 | Northern Ghana | 160 | 38.19 |

| Total | 419 | 100 | Total | 419 | 100 |

| School category | Age (in years) | ||||

| A | 78 | 18.62 | 20–29 | 159 | 37.95 |

| B | 202 | 48.21 | 30–39 | 170 | 40.57 |

| C | 139 | 33.17 | 40 and above | 90 | 21.48 |

| Total | 419 | 100 | Total | 419 | 100 |

| Experience (in years) | |||||

| 1–5 | 179 | 42.72 | |||

| 6–10 | 110 | 26.25 | |||

| 11–15 | 80 | 19.09 | |||

| 16–20 | 40 | 9.55 | |||

| 20+ | 10 | 2.39 | |||

| Total | 419 | 100 |

In terms of teachers' educational qualifications, a cross-tabulation with teacher self-efficacy levels was performed (See Table 2). This is an initial step in understanding the distribution of teacher self-efficacy levels according to their educational qualifications. According to the results in Table 2, 279(66.59%) of the teachers had bachelor's degrees, while 140(33.41%) had master's degree. The majority of the teachers had high efficacy levels (281, 67.06%), while 138(32.94%) had moderate efficacy levels, suggesting that the level of efficacy among the teachers is either high or moderate. 169(40.33%) and 110(26.25%) of the participants had bachelor's degrees with high and moderate efficacy levels, respectively. 112(26.73%) of the participants had master's degrees with high teacher self-efficacy levels but only 28(6.68%) of the participants had master's degrees with a moderate efficacy level. This suggests that teachers with master's degrees predominantly had a high efficacy level.

| Teacher educational qualification | Teacher self-efficacy levels | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | High | Total | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Bachelor | 110 | 26.25 | 169 | 40.33 | 279 | 66.59 |

| Master | 28 | 6.68 | 112 | 26.73 | 140 | 33.41 |

| Total | 138 | 32.94 | 281 | 67.06 | 419 | 100.00 |

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for QTSIs and teacher self-efficacy variables, which were measured on a Likert scale. According to the results in Table 3, a mean of 6.153 (SD = 0.381) on a 7-point scale indicates high QTSIs. Similarly, a mean of 7.203 (SD = 0.954) on a 9-point scale suggests a high teacher self-efficacy level.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTSIs | 419 | 6.153 | 0.381 | 5 | 7 |

| Teacher self-efficacy | 419 | 7.203 | 0.954 | 5 | 9 |

Although the scales were adopted, in accordance with the recommendations of Thompson (2002) and Taherdoost (2016), we provided the final reliabilities (α) and discriminant validity (the bolded figures in the diagonals) for QTSIs and TEL scales, as well as correlation and collinearity statistics results for all the variables (see Table 4). The reliabilities of the adopted scales were confirmed in this study, with Cronbach's alphas of 0.860 and 0.896, respectively, for QTSIs and TEL, indicating good internal consistency (Bland & Altman, 1997). The discriminant validities were also supported, showing that the scale items load more strongly on construct QTSIs and TEL (see the bolded values) than on other theoretically unrelated constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Smith & Combs, 2010).

| α | Correlation results | Collinearity statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTSIs | QUAL | SL | SC | Sex | Age | Yrs | TEL | VIF | TOL | ||

| QTSIs | 0.860 | 0.851 | |||||||||

| QUAL | - | 0.200*** | - | 1.15 | 0.870 | ||||||

| SL | - | 0.035 | 0.036 | - | 1.31 | 0.763 | |||||

| SC | - | 0.092* | 0.076* | 0.274*** | - | 2.17 | 0.461 | ||||

| Sex | - | 0.278*** | 0.105** | 0.138** | 0.070* | - | 1.15 | 0.870 | |||

| Age | - | 0.226*** | 0.181** | 0.024 | 0.167** | 0.276*** | - | 3.40 | 0.294 | ||

| Yrs | - | 0.087* | 0.201*** | 0.204*** | 0.125** | 0.192*** | 0.721*** | - | 3.12 | 0.321 | |

| TEL | 0.892 | 0.597*** | 0.137** | 0.185** | 0.403*** | 0.119** | 0.180** | 0.097* | 0.883 | 2.43 | 0.412 |

- Note: Outcome Variable is QTSIs. Bolded values are the discriminant validity results.

- Abbreviations: EXP, experience; QTSIs, teacher-student interactions; QUAL, teacher educational qualifications; SC, school category; SL, school location; TEL, teacher self-efficacy; TOL, total; VIF, variance inflation factor; Yrs, years of experience.

- ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

The correlation results show that the explanatory variables correlated with the outcome variables, suggesting an association between the explanatory variables and the outcome variable. In terms of determining the presence of multicollinearity, the rule of thumb is that the correlation among the explanatory variables should not exceed 0.70 and the tolerance (TOL) should be greater than 0.2, while the variance inflation factor (VIF) should not exceed 10 (Dormann et al., 2013). From Table 4, all the correlation values among explanatory variables were below 0.70. Similarly, the TOL and VIF values, respectively, are greater than 0.2 and less than 5, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a problem in this study.

4.1 Hypothesis testing

To proceed to decompose teacher educational qualifications into bachelor's and master's degrees to establish their respective influence on QTSIs, we tested whether there is a significant difference in the mean scores of QTSIs between the two levels of qualifications. The t-test results are presented in Table 5. According to the results in Table 5, there is a significant difference (p < .001) in the mean QTSI scores between teachers with bachelor's and master's degrees in favor of master's degree teachers. This provides initial justification for decomposing teacher educational qualifications in their respective levels (bachelor and master) to understand how different qualifications contribute to QTSIs.

| Group | Mean | DF | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor's | 6.099 | 417 | −4.169*** | 0.000 |

| Master's | 6.260 |

- Abbreviations: DF, degree of freedom; t, t-statistics; p, probability.

- ***p < .001.

We estimated the influence of teacher educational qualifications on QTSIs using three approaches. The first (1) and second (2) approaches analyzed the relationship among the variables for teachers with bachelor's and master's degrees, respectively. The third (3) approach provides the estimate for all the teachers but benchmarked bachelor's degree teachers to enable us to determine how much more those with master's degrees will perform than those with bachelor's degrees. Table 6 presents the results.

| QTSIs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| Coef. | T-stats | Coef. | T-stats | Coef. | T-stats | |

| Bachelor's | 0.102*** | 3.167 | ||||

| Master's | 0.305*** | 7.335 | ||||

| Qualification | 0.204*** | 6.330 | ||||

| School location | 0.060* | 1.806 | 0.065* | 1.906 | 0.063* | 1.900 |

| School category | 0.162*** | 6.961 | 0.159*** | 7.250 | 0.171*** | 7.330 |

| Sex | 0.293*** | 6.093 | 0.278*** | 4.475 | 0.308*** | 6.410 |

| Age | 0.357*** | 11.310 | 0.383*** | 10.291 | 0.375*** | 11.900 |

| Experience | 0.223*** | 10.348 | 0.281*** | 10.132 | 0.234*** | 10.890 |

| Constant | 5.708*** | 60.358 | 6.965*** | 56.910 | 5.600*** | 53.060 |

| F-test | 41.47*** | 43.15*** | 46.28*** | |||

| R-squared | 0.377 | 0.381 | 0.394 | |||

- ***p < .001, *p < .1.

In all three estimates, the demographic variables except SL had a controlling effect on QTSIs. In terms of estimates (1 and 2), the coefficient of 0.102 and 0.305, respectively, indicates that bachelor's and master's degrees as teacher educational qualifications had statistically significant and positive influence on QTSIs. This suggests that both bachelor's and master's degrees are necessary for improving the QTSIs in SHSs. This finding partly supports 1, which states that teacher educational qualifications will have a statistically significant positive influence on QTSIs. However, comparing the coefficients, teachers with master's degrees (β = 0.305) are in a much better position to improve QTSIs than those with bachelor's degrees (β = 0.102); other variables held constant. The coefficient of 0.204 results from the model (3) (which benchmarked bachelor's degree) indicates the difference in the expected QTSIs between teachers with master's and bachelor's degrees when all other variables such as age, sex, SL, SC and years of experience in the model are held constant. Specifically, it suggests that, on average, a master's degree tends to increase the QTSIs level by 0.204 units than a bachelor's degree. This finding partly supports 1, which states that teachers with master's degrees will promote QTSIs in the classroom more than those with bachelor's degrees.

The second analysis focused on establishing whether teacher self-efficacy plays a role in the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs. We performed this analysis for all teachers regardless of their qualifications, followed by teachers with bachelor's degrees and master's degrees, to provide an in-depth understanding of the relationships. Before performing the main analysis, we determined whether there are differences in mean efficacy scores between bachelor's and master's degree teachers, as well as high and moderate teacher self-efficacy levels.

The t-test results in Table 7 showed a significant difference in efficacy scores between bachelor's and master's degree teachers, as well as high and moderate efficacy levels. These results demonstrated the need to decompose the qualifications and efficacy variables in this study (See Table 8).

| Group | Mean | DF | t | p | Group | Mean | DF | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor | 7.110 | 417 | −2.828*** | 0.003 | High | 7.901 | 417 | 7.423*** | 0.000 |

| Master | 7.387 | Moderate | 5.296 |

- ***p < .001.

| Variables | Dependent variable: QTSIs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All teachers | Masters | Bachelor | BMoTEL | BHTEL | ||||||

| 1a | 1b | 2a | 2b | 3a | 3b | 4a | 4b | 5a | 5b | |

| QUAL | 0.130*** (4.17) | 0.429*** (2.93) | ||||||||

| Master's degree | 0.147*** (4.24) | 0.465*** (3.30) | ||||||||

| Bachelor's degree | 0.125*** (4.03) | 0.416*** (3.02) | 0.123*** (3.96) | 0.282*** (3.08) | 0.131*** (4.22) | 0.449*** (3.16) | ||||

| School location | 0.023 (0.72) | 0.045 (1.36) | 0.024 (0.83) | 0.046 (1.53) | 0.022 (0.71) | 0.041 (1.38) | 0.050 (0.79) | 0.006 (0.52) | 0.052 (0.84) | 0.013 (0.66) |

| School category | 0.016 (0.54) | 0.016 (0.57) | 0.016 (0.59) | 0.016 (0.64) | 0.016 (0.55) | 0.014 (0.59) | 0.021 (0.53) | 0.018 (0.55) | 0.024 (0.57) | 0.019 (0.58) |

| Sex | 0.238*** (5.24) | 0.227*** (5.00) | 0.241*** (5.53) | 0.230*** (5.62) | 0.232*** (5.23) | 0.223*** (5.04) | 0.227*** (5.26) | 0.224*** (5.02) | 0.239*** (5.38) | 0.231*** (5.44) |

| Age | 0.162*** (4.13) | 0.160*** (4.12) | 0.164*** (4.18) | 0.162*** (4.64) | 0.160*** (4.13) | 0.157*** (4.11) | 0.158*** (4.20) | 0.156*** (4.26) | 0.173*** (4.29) | 0.159*** (4.35) |

| Teaching experience | 0.096*** (3.67) | 0.091*** (3.51) | 0.097*** (3.72) | 0.093*** (3.96) | 0.092*** (3.66) | 0.088*** (3.46) | 0.086*** (3.58) | 0.084*** (3.41) | 0.095*** (3.67) | 0.091*** (3.43) |

| TEL | 0.184*** (8.18) | 0.300*** (5.78) | 0.196*** (8.26) | 0.304*** (6.51) | 0.176*** (8.14) | 0.292*** (5.69) | ||||

| MoTEL | 0.179*** (8.02) | 0.218*** (5.73) | ||||||||

| HTEL | 0.204*** (7.20) | 0.302*** (5.79) | ||||||||

| QUAL × TEL | 0.095** (2.48) | 0.098** (2.80) | 0.091** (2.39) | |||||||

| BACH × MoTEL | 0.073* (1.94) | |||||||||

| BACH × HTEL | 0.097**(2.62) | |||||||||

| Constant | 4.350*** (23.97) | 3.538*** (9.47) | 5.056*** (24.33) | 4.814*** (26.10) | 4.611*** (24.04) | 5.196*** (17.13) | 5.981*** (26.34) | 5.990*** (23.09) | 5.983*** (22.87) | 5.993*** (19.96) |

| F-test | 50.80*** | 45.78*** | 50.93*** | 44.69*** | 50.53*** | 41.47*** | 54.10*** | 46.22*** | 54.85*** | 43.19*** |

| R-squared | 0.464 | 0.472 | 0.466 | 0.476 | 0.462 | 0.467 | 0.461 | 0.469 | 0.465 | 0.472 |

- Note: T-statistics are in parentheses(). Models 1a, 2a, 3a, 4a, and 5a were estimated for comparison purposes.

- Abbreviations: BACH, Bachelor's Degree; BHTEL, BACH with High Efficacy; BMoTEL, BACH with Moderate Efficacy; HTEL, High Teacher Efficacy; MoTEL, Moderate Teacher Self-Efficacy; QUAL, Teacher Educational Qualifications.

- *p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

To minimize multicollinearity and ensure more stable estimates of regression coefficients and interpretability of results, the moderator variable (teacher self-efficacy) was mean-centered, a common practice in moderation analysis (Quansah et al., 2023). From Table 8, model 1b (qualification in general), the coefficient of the interaction terms of qualifications and teacher self-efficacy (QUAL × TEL) is positive and significant, indicating that teacher self-efficacy has a moderating impact on the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs. This implies that teacher educational qualifications combined with teacher self-efficacy level will enhance QTSIs.

In terms of qualification specifics, the results in model 2b (master's degree qualification) show that the coefficient of the interaction terms of master's degree and teacher self-efficacy (QUAL × TEL) is positive and significant indicating that teacher self-efficacy has a moderating impact on the relationship between master's degree qualification and QTSIs. Thus, a master's degree qualification moderated by teacher self-efficacy will increase QTSIs. Similarly, the results in model 3b (bachelor's degree qualification) show that the coefficient of the interaction terms of bachelor's degree qualification and teacher self-efficacy (QUAL × TEL) is positive and significant, indicating that teacher self-efficacy has a moderating impact on the relationship between bachelor's degree qualification and QTSIs. Therefore, a bachelor's degree qualification moderated by the teacher's efficacy level will improve QTSIs. Comparatively, the marginal impact of teacher self-efficacy moderating teacher educational qualifications is stronger for teachers with master's degrees (β = 0.098) than those with bachelor's degrees (β = 0.091) and all teachers put together (β = 0.095). This finding provides support for 2.

Finally, we disaggregated the level of efficacy of teachers with bachelor's degrees into moderate and high to determine whether improving their efficacy, especially in the short term, could bridge the qualification gap with a master's degree. As represented in model 4b, the coefficients of the interaction term (BACH × MoTEL) of bachelor's degree qualification (BACH) and moderate teacher self-efficacy (MoTEL) are positive but weak in statistical power (10% significance level). This shows that BACH moderated by MoTEL enhances QTSIs, but its impact cannot be statistically proven (p > .05). In contrast, the coefficients (model 5b) of the interaction term (BACH × HTEL) of BACH and high teacher self-efficacy (HTEL) are positive and statistically significant, indicating that BACH moderated by HTEL will promote QTSIs.

Interestingly, the coefficient of the interaction term (BACH × HTEL) is 0.097, which is more than the moderating impact of BACH × MoTEL (β = 0.073) and QUAL × TEL (β = 0.091) but closer to a master's degree and teacher self-efficacy (β = 0.098). This implies that high teacher self-efficacy has a stronger moderating influence on teacher educational qualification (bachelor) and has the potential to close the qualification gap than moderate teacher self-efficacy. This finding is in support of 3.

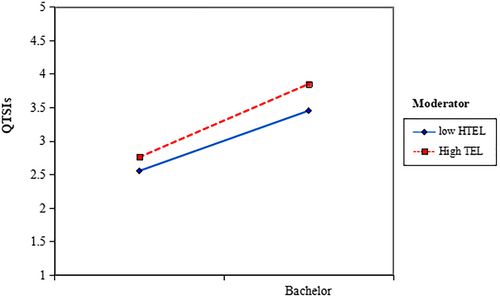

4.2 Moderating graphs

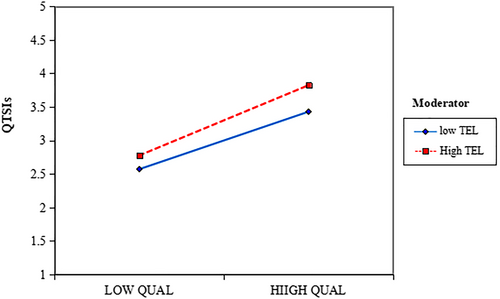

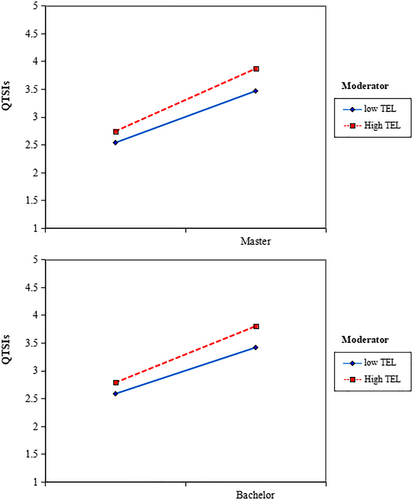

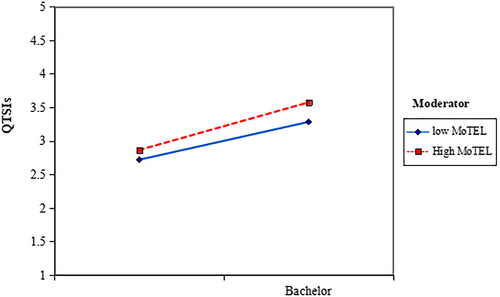

As a normal practice in moderation analysis, we provided moderating graphs to provide visual support for the moderating results in Table 8. Figure 2 shows that the higher the TEL (denoted by red dotted lines), the higher the influence of QUAL on QTSIs, supporting the results in Table 8 (model 1b). Similarly, Figure 3 shows that teacher self-efficacy moderated the relationship between master and QTSIs and bachelor and QTSIs, providing further evidence to support the results in models 2 and 3b of Table 8. In terms of Figures 4 and 5, where the efficacy of a bachelor's degree was decomposed into high (HTEL) and moderate (MoTEL) efficacy levels, the results show that both efficacy levels moderated the relationship between bachelor's degree qualification and QTSIs. When comparing their moderating impacts on QTSIs, the results displayed in Figure 5 reveal that HTEL exhibits a stronger influence, reaching 4 (closer to that of the moderating influence established for master's degree teachers in Figure 3). In contrast, MoTEL, depicted in Figure 4, shows an approximate rating of 3.5. Finally, Figure 6 illustrates the overall results of the moderating effects of the teacher efficacy level on the relationship between teacher educational qualifications (master's and bachelor's degrees) and the QTSIs.

Moderating effect of teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and quality of teacher–student interactions. QTSIs, teacher-student interactions; TEL, teacher self-efficacy.

Moderating effects of teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between teacher educational qualifications (bachelor and master) and quality of teacher–student interactions. QTSIs, teacher-student interactions; TEL, teacher self-efficacy.

Moderating effect of moderate teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between bachelor and quality of teacher–student interactions. QTSIs, teacher-student interactions; TEL, teacher self-efficacy.

Moderating effect of high teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between bachelor and quality of teacher–student interactions. QTSIs, teacher-student interactions; TEL, teacher self-efficacy.

Moderating effects of teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between teacher educational qualifications (Master's and Bachelor's degrees) and Quality of Teacher-Student Interactions. QTSIs, teacher-student interactions; TEL, teacher self-efficacy.

5 DISCUSSION

This study revealed that teacher educational qualifications had a significant positive influence on QTSIs, with master's qualifications having a stronger impact. This was expected since the analysis of the differences in QTSIs revealed that teachers with master's degrees had relatively higher QTSIs than those with bachelor's degrees. The results show that higher teachers' educational qualifications play a key role in improving QTSIs, providing empirical evidence to support Ghana Education Service (2019) policy measures that set a bachelor's degree in education as a minimum qualification for teaching in SHSs in Ghana. While this study contradicts the findings of previous studies, such as Buddin and Zamarro (2009) who reported no influence of teacher educational qualifications on educational outcomes in California, it provides empirical evidence to support the studies of Mugoya et al. (2022) and Owusu and Yiboe (2013) which revealed positive associations between the variables in Ghana and Uganda, respectively.

Notwithstanding, the present study further revealed that a master's degree has stronger influence on QTSIs than a bachelor's degree, indicating a master's degree as a prioritized qualification for achieving QTSIs compared to a bachelor's degree. This is not to suggest that teachers with only a bachelor's degree are ineffective toward QTSIs. Bachelor's degree holders also possess valuable knowledge and skills acquired through their undergraduate education. However, the result suggests that the advanced education and specialized training obtained through a master's degree program bring additional benefits and contribute to a stronger impact on teacher–student interactions (Mugoya et al., 2022). Teachers with a master's degree may have a deeper knowledge of subject matter content, allowing them to provide more in-depth instruction and respond effectively to students' questions and needs, in line with the theoretical proposition of human capital theory (Belay et al., 2021; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012). Given Ghana's continued shortage of trained and qualified teachers, owing primarily to a lack of robust support systems, incentives, and comprehensive frameworks for teachers to improve their qualifications, this finding highlights the urgent need to intensify efforts to achieve SDG 4.c (substantial increase in the supply of quality teachers). With attention to SDG 4c, Ghana has the potential to improve QTSIs in SHSs.

Teacher self-efficacy had a positive moderating influence on the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs. The findings of this study align with Gelaidan et al. (2023) and Parmaksız (2022), who found the moderating influence of self-efficacy. However, this study's findings show the crucial role of teacher self-efficacy in determining the impact of teacher educational qualifications on QTSIs. When teachers have a high sense of efficacy, their educational qualifications exert a stronger and more positive influence on QTSIs. Teacher self-efficacy can help teachers look beyond challenges or limitations and build resilience toward improving QTSIs (Glassow et al., 2023; Heng & Chu, 2023). Notably, the moderating effect was found to be more pronounced for teachers with a master's degree compared to those with a bachelor's degree qualification. These findings are consistent with our preliminary results, which indicated higher mean teacher efficacy scores among teachers with master's degrees compared to those with bachelor's degrees. This suggests that a combination of high efficacy and advanced educational qualifications enhances teachers' interactions with their students, leading to improved student outcomes (Hidayah et al., 2023). These results imply that teachers who have confidence in their abilities and possess advanced knowledge and skills are more likely to cultivate positive and effective student interactions, thereby promoting their academic and socio-emotional development (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007).

Finally, the study revealed that a higher teacher self-efficacy level has a stronger moderating influence on the relationship between bachelor's degree qualification and QTSIs compared with a moderate teacher self-efficacy level. This finding provides strong empirical support for the moderating role of teacher self-efficacy, which is underdevelopment. A teacher with a bachelor's degree and high efficacy can potentially have comparable abilities in fostering skills and resilience to promote positive classroom interactions as a teacher with a master's degree (Glassow et al., 2023). The high efficacy level of the teacher with a bachelor's degree can compensate for the difference in educational qualifications. A high level of teacher self-efficacy ignites teacher enthusiasm (Zhang & Ye, 2023). It serves as a motivating force that drives teachers to persevere and engage in continuous learning, leading to the improvement of teaching and learning quality (Brenner, 2022). When teachers possess a strong belief in their abilities to impact student outcomes positively, they are more inclined to invest effort in professional development, seek out innovative teaching strategies, and actively pursue opportunities for growth (Brenner, 2022). This intrinsic motivation stemming from high efficacy levels encourages teachers to persist in their efforts to enhance their instructional practices, adapt to the evolving needs of their students, and employ effective pedagogical approaches (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007). Although higher efficacy closed the marginal impacts between teachers with bachelor's and master's degrees, it could not fully bridge the gap. This shows that higher teacher self-efficacy should not be seen as a substitute for advanced education qualifications, as having a higher efficacy and advanced education qualification has a stronger impact on QTSIs.

6 CONCLUSION

The study explored teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs and the potential of teacher self-efficacy in bridging the qualification gap. Using t-tests and ordinary least squares estimators, the empirical analysis of data drawn from SHS teachers in Ghana sheds light on several significant findings, contributing to our understanding of this complex educational landscape. The results demonstrated a positive influence of teacher educational qualifications on QTSIs, with a master's degree qualification having a stronger impact than a bachelor's degree. It was revealed that teacher self-efficacy positively moderated the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs. While higher teacher self-efficacy showed its potential in bridging the educational gap between bachelor's and master's degrees regarding QTSIs, it could not fully offset the disparity. This finding highlights the multifaceted nature of educational qualifications and teacher self-efficacy in the teaching profession. In the next sections, we discuss implications for theory, practice, limitations, and future research directions.

6.1 Implications for theory

The findings of this study contribute to the theoretical understanding of the relationship between teacher educational qualifications and educational outcomes, particularly QTSIs in SHS classrooms in Ghana. The study reveals a positive influence of teacher educational qualifications on QTSIs, indicating that higher qualifications, such as a master's degree, are associated with improved interactions compared to lower qualifications, such as a bachelor's degree. This finding supports the prepositions of the human capital theory. It aligns with existing literature that suggests higher education levels can enhance teachers' knowledge and skills, thereby positively impacting their interactions with students. Furthermore, the moderating effect of teacher self-efficacy is based on self-efficacy and social cognitive theoretical perspectives on self-beliefs shaping individual abilities and effectiveness. The teacher's self-efficacy findings also demonstrate the usefulness of these theoretical lenses in educational discussions, especially within the classroom context. Although teacher self-efficacy significantly affected the qualification–interactions relationship, its influence had limits as the qualification gap was only partially bridged. This indicates that efficacy alone cannot fully substitute advanced education, suggesting avenues for exploring other factors.

6.2 Implications for practice

This study has some practical implications for policymakers, educators, and teacher training programs in Ghana. First, the positive relationship between teacher educational qualifications and QTSIs implies that the Ministry of Education and the Ghana Education Service continue to enforce a bachelor's degree in education or its equivalent as the minimum qualification for SHS teachers. This baseline educational qualification is needed not only to achieve SDG 4.c (supply of qualified teachers) but also SDG 4 (quality education) through QTSIs. Since teachers with master's degrees generally had higher levels of QTSIs than those with bachelor's degrees, the Ministry of Education, Ghana Education Service, and school administrators should prioritize and incentivize advanced degree attainment for teachers, as it correlates with improved teaching effectiveness. They should also encourage and support teachers to attain higher qualifications to enhance QTSIs.

Second, the moderating influence of teacher self-efficacy implies that teacher training programs offered across education faculties across Ghana should incorporate strategies for building teacher self-efficacy into their curriculum and instructional practices. Particularly, teachers with bachelor's degrees had lower efficacy level compared to those with master's degrees, necessitating teacher education programs across the universities in the country to incorporate strategies for building teacher self-efficacy into their curriculum and instructional practices since teaching efficacy primarily emerges during the initial stages of teacher education (Ekstam et al., 2017). For in-service teachers, efficacy building should be included in their ongoing professional development programs and in-service training with a focus on providing constructive feedback, improving teachers' skills, and creating supportive work environments. However, it must be emphasized that higher teacher self-efficacy alone cannot fully bridge the qualification gap. A balanced approach is crucial, necessitating policymakers, teacher educators, and administrators to provide an enabling environment to support teachers' higher education and enhance their self-efficacy to improve QTSIs in SHS classrooms in Ghana.

6.3 Limitations and future research directions

Although it is useful for gathering numerical data, the use of questionnaires and a quantitative approach may not adequately capture the complexity of teacher–student interactions and can lead to response biases. Qualitative methods such as interviews with teachers on their experiences orchestrating effective classroom interactions and observations of teacher–student interactions in classroom contexts could provide an in-depth understanding of how teacher efficacy might impact engaging and rich classroom interactions. Secondly, the findings may not be generalized beyond Ghana's SHS classrooms. Thirdly, the cross-sectional nature of the survey limits the exploration of temporal changes and contextual influences. While recognizing the limitations, it is important to acknowledge that the study followed rigorous quantitative methods to address common method biases and implement statistical controls and procedures to produce valid and reliable results. Future research could employ diverse approaches, consider broader contexts, and utilize longitudinal or experimental designs to deepen the understanding of the complex dynamics between teacher educational qualifications, teacher self-efficacy, and QTSIs.

Author contributions

Albert Henry Ntarmah: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; software; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Kwesi Yaro: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am thankful to the teachers who participated in this study and their authorities including heads, administrators, and heads of departments. I am grateful to the research assistants who helped in the data collection and other researchers, whose constructive feedback shaped this study. The author did not receive any funding for this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author declares no conflicting interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study complied with the Ethical Code of Conduct of the American Psychological Association and the Declaration of Helsinki. The heads or assistant heads of the participating schools in collaboration with the school management approved the research protocol prior to data collection. Confidentiality, voluntary participation, and anonymity of the participants were assured.

INFORMED CONSENT

Participants provided informed consent.

Biographies

Albert Henry Ntarmah is a Doctoral Student at the University of Alberta, Canada. His research areas include teaching mathematics for sustainable development, Indigenous Knowledge, teacher education, and curriculum and teaching. Albert's research aims to enhance mathematics teaching and learning by integrating culturally responsive pedagogy, ecojustice, and sustainable development to make mathematics meaningful to students' local and global contexts.

Dr Kwesi Yaro is an Assistant Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. His research is primarily grounded in situated and critical perspectives, drawing from principles of cultural sustainability, social justice, and inclusion. His research areas encompass the utilization of African Indigenous Knowledge to elucidate Sub-Saharan African immigrant families' engagement in their children's mathematics education; mathematics teaching and learning in rural contexts; race and racialization in mathematics education; and pedagogical approaches for teaching mathematics for sustainable development.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.