MRI evidence for material-specific encoding deficits and mesial–temporal alterations in presurgical frontal lobe epilepsy patients

Abstract

Objective

Neuroimaging studies reveal frontal lobe (FL) contributions to memory encoding. Accordingly, memory impairments are documented in frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE). Still, little is known about the structural or functional correlates of such impairments. Particularly, material specificity of functional changes in cerebral activity during memory encoding in FLE is unclear.

Methods

We compared 24 FLE patients (15 right-sided) undergoing presurgical evaluation with 30 healthy controls on a memory fMRI-paradigm of learning scenes, faces, and words followed by an out-of-scanner recognition task as well as regarding their mesial temporal lobe (mTL) volumes. We also addressed effects of FLE lateralization and performance level (normal vs. low).

Results

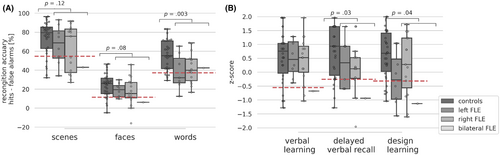

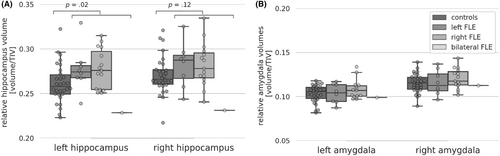

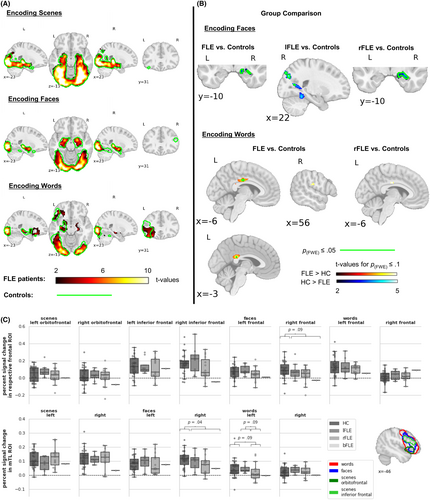

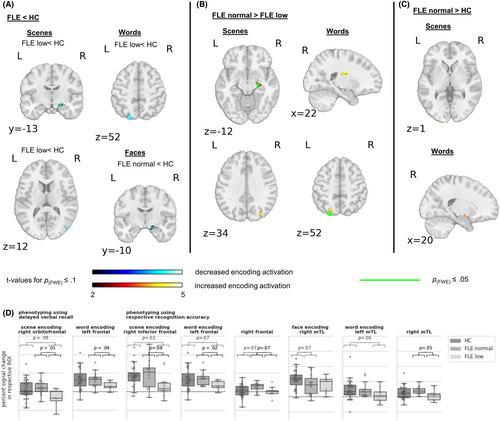

FLE patients had poorer memory performance and larger left hippocampal volumes than controls. Volume increase seemed, however, irrelevant or even dysfunctional for memory performance. Further, functional changes in FLE patients were right-sided for scenes and faces and bilateral for words. In detail, during face encoding, FLE patients had, regardless of their performance level, decreased mTL activation, while during scene and word encoding only low performing FLE patients had decreased mTL along with decreased FL activation. Intact verbal memory performance was associated with higher right frontal activation in FLE patients but not in controls.

Significance

Pharmacoresistant FLE has a distinct functional and structural impact on the mTL. Effects vary with the encoded material and patients' performance levels. Thus, in addition to the direct effect of the FL, memory impairment in FLE is presumably to a large part due to functional mTL changes triggered by disrupted FL networks.

Plain Language Summary

Frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) patients may suffer from memory impairment. Therefore, we asked patients to perform a memory task while their brain was scanned by MRI in order to investigate possible changes in brain activation during learning. FLE patients showed changes in brain activation during learning and also structural changes in the mesial temporal lobe, which is a brain region especially relevant for learning but not the origin of the seizures in FLE. We conclude that FLE leads to widespread changes that contribute to FLE patients’ memory impairment.

Key points

- Presurgical frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) patients have verbal and nonverbal memory impairments.

- Presurgical FLE patients have increased left hippocampal volumes.

- Presurgical FLE patients have decreased hemodynamic activation during encoding especially in the mesial–temporal lobe.

1 INTRODUCTION

In temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), memory impairments have been extensively investigated, as the temporal lobe (TL) is closely associated with memory formation. However, studies suggest that patients with frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE), the second most common type of focal pharmacoresistant epilepsy,1 are also prone to memory deficits.2 In fact, a recent behavioral study comparing large and well-matched groups of TLE and FLE patients found no difference in the extent of verbal memory impairment between groups, neither pre nor postoperatively.3 In line with memory impairment in FLE, current theory suggests that the memory network comprises frontal and parietal regions in addition to TL structures.4 The importance of frontal lobe (FL) structures for memory is underlined by neuroimaging studies5 which reveal their involvement in both encoding and retrieval. Overall, studies suggest a material-specific impact with word encoding being associated with primarily left frontal activation, while face encoding is associated with more right than left frontal activation.6 Scene encoding typically elicits bilateral to slightly right-lateralized frontal activation.7

First neuroimaging studies on FLE hint not only at structural and functional disruptions in the FL itself. They further indicate that FLE patients might have structural and functional disruptions in core memory structures distal to the FL, especially the mesial TL (mTL).8, 9

Structural changes in FLE patients were found in terms of volume reductions of white matter bundles10 and cortical thinning11 in various regions. Regarding TL structures, studies showed reduced left lateral TL12 and increased bilateral mTL volumes.9 In contrast, other studies did not find mTL volume changes.8, 13 To the best of our knowledge, none of these studies correlated structural changes with memory performance.

In addition to investigating structural changes, it is informative to study functional changes in FLE patients to elucidate the contribution of the FL to memory. This may also help to predict postoperative memory impairment in a similar way as in TLE.14-16 To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study investigating functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) correlates of episodic memory in FLE patients.8 This study compared 18 controls with 32 predominantly nonlesional FLE patients (19 left, 13 right, eight with established frontal lesions) regarding encoding of line-drawn objects, faces and words. Across stimulus types, FLE patients showed more frontal activation than controls, especially contralateral to seizure focus. Further analyses revealed that these frontal activation increases were restricted to patients with normal memory performance. By contrast, patients with low memory performance showed decreased hippocampal activation.

Here, we study possible functional and structural impacts of FLE on core memory structures, including the mTL. Going beyond a previous study we investigate whether and how fMRI activation in FLE patients varies with the type of encoding material. Further, we examine the association between memory performance and both structural changes and functional activation in the mTL. Therefore, we applied a memory fMRI-paradigm of learning scenes, faces and words, that we previously used to elicit robust activations throughout the brain including the mTL,17 in a group of FLE patients with predominantly structural etiology undergoing presurgical evaluation.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

We studied 25 FLE patients, who were consecutively recruited from the presurgical epilepsy monitoring unit at The Mara, Bielefeld, Germany, and 30 controls (largely overlapping with the previously published control sample17). One patient who reported to have fallen asleep during the experiment was excluded. Two additional patients were excluded from the verbal encoding condition only: one right FLE (rFLE) patient, because of deficient German, and one left FLE (lFLE) patient who reported not having seen the words but only scenes and faces clearly.

FL origin and lateralization of the patient's epileptic onset zone were ascertained by presurgical diagnostics (using semiology, MRI, noninvasive long-term-video-EEG-monitoring [about 1 week], and if available invasive recordings). Requirements for controls’ participation were an age ≥18 and absence of known neurological and psychiatric disorders. Table 1 details participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Controls n = 30 | FLE n = 24 | |

|---|---|---|

|

Age in years [M (SD) (range)] |

35.4 (13.3) (19–60) |

32.5 (12.7) (18–65) |

| Sex in % [male/female] | 50.0/50.0 | 58.3/41.7 |

|

Years of schooling [M (SD)] (range) |

10.6 (1.6) (9–13) |

10.8 (1.4) (9–13) |

| Handedness [right/left] | 28/2 | 22/2 |

|

Language lateralitya [left/bilateral] |

22/2 | |

|

Laterality of epileptic focus [left/right/bilateral] |

8/15/1 | |

|

Age at epilepsy onset [M (SD)] [(range)] |

15.1 (14.9) (0–62) |

|

|

Epilepsy duration [M (SD)] [(range)] |

17.4 (9.2) (0–34) |

|

|

Antiseizure medication loadb [Mdn (range)] |

2.6 (1.0–5.4) |

|

|

Etiology [absolute numbers (lFLE)] Focal cortical dysplasia/unspecified dysplastic lesion/cyst/cavernoma/tumor/no lesion |

13 (4)/ 4 (1)/ 1 (0)/ 2 (1)/ 2 (1)/ 2 (1) |

|

|

Surgical outcomec no surgery/1a/3a |

8/14/2 |

- Note: There was no statistically significant difference between controls and FLE patients regarding age, sex, years of schooling and handedness (ps > .3). The effect of language laterality and etiology on the outcome measures was explored in Supplementary Information V in the Appendix S1.

- Abbreviation: FLE, frontal lobe epilepsy.

- a Language laterality was determined by language fMRI.18

- b The antiseizure medication load was estimated as the sum of the ratios (prescribed daily dose/defined daily dose) for each antiseizure medication, with the doses corresponding to those defined by the World Health Organization. One patient took 100 mg/day Topiramate, none took Zonisamide.

- c According to Engel19 at 6-month (9 patients) or 24-month after surgery (7 patients).

Before participation, all participants gave written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committees of Bielefeld University (EUB 2017-080) and Westphalia-Lippe Medical Association (Münster, 2018-090-f-S) approved the study.

2.2 Neuropsychological testing

Participants underwent neuropsychological testing including verbal and visual memory assessment using the German adaption of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning and Memory Test20 (Verbaler Lern- und Merkfähigkeitstest,21 VLMT) and the Diagnosticum für Cerebralschädigung II22 (DCS), respectively. In the VLMT, participants listened to five repetitions of the same list of 15 unrelated words, which had to be freely recalled immediately after each presentation. Then, participants listened to an interference list, which had to be freely recalled, too. Immediately afterwards and again after a 30-min delay participants had to freely recall the primary list again. In the DCS, participants were presented 9 geometrical figures 5 times for 10 s each and, after each presentation, asked to reproduce the memorized figures with wooden sticks. For both tests, the standardized, age-(and education-) corrected z-scores of the sum of recalled items across five trials were calculated according to published norms. Only for the VLMT, the sum of recalled items after 30 min was also assessed.

2.3 Memory fMRI-paradigm

The memory fMRI-paradigm comprised 72 scenes, faces and words, respectively, for details, see ref. [17] and Table S1. In three randomized consecutive runs, the stimuli of each condition were presented for 3 s each in alternating blocks of four neutral or negative stimuli. Each block was followed by a 12 s baseline condition. Participants were instructed to memorize the stimuli for subsequent recognition. In the baseline condition, participants were requested to maintain fixation at a randomly moving dot and to avoid thinking about the preceding stimuli.

The out-of-scanner recognition task immediately followed the fMRI-task. For each condition all 72 old and 48 new stimuli were presented and participants had to decide whether the stimulus had been shown in the MRI.

2.4 MRI acquisition and preprocessing

MRI data were collected on a 3T Siemens Verio MRI scanner. For fMRI, 37 coronal slices aligned with the long axis of the hippocampus were acquired. We preprocessed MRI data using fMRIPrep 1.4.1rc4.23 For further details on anatomical and functional MRI data acquisition and preprocessing ref.17

2.5 Statistical analyses

2.5.1 Behavioral data

We compared FLE patients with controls regarding percentage of hits and false alarms, recognition accuracy (hits – false alarms) and response bias (false alarms/[100 – recognition accuracy])24 of the recognition task following fMRI separately for each condition and regarding verbal learning, delayed verbal recall and design learning. Because data were partly nonnormally distributed, we used the Mann–Whitney-U-test to compare groups (ptwo-sided ≤ .05). We did not correct for multiple comparisons in the behavioral data, due to the exploratory character of the study, because of the given sample size, and the general flexibility for choosing the number of tests to adjust for, which makes correction often arbitrary and thus spurious.25, 26

2.5.2 mTL volumes

Hippocampal and amygdala volumes were estimated using recon-all from Freesurfer 6.0.1 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) as implemented in the fMRIprep pipeline.27, 28 We accounted for possible differences in whole brain volumes using the region-to-total intracranial volume ratio [respective brain volume in mm3/total intracranial volume *100]. To explore associations between mTL volumes and memory performance, we calculated correlations and further compared memory performance between patients with normal and abnormal hippocampal volumes according to the 84th percentile of controls.

2.5.3 fMRI data

For details on the first level analysis, see ref. [17]. In short, these were conducted using the Python package Nistats 0.0.1b1. Regressors of interest were the three stimulus modalities, each convolved with the canonical double gamma hemodynamic response function.

For the second level analyses, one-sample t-tests were used to examine main effects of encoding elicited by each modality separately for FLE patients and controls and two sample t-tests to compare groups within each modality. We also exploratively compared lFLE and rFLE patients with controls. FSL 6.0 (FMRIB Software Library) randomize 2.9 nonparametric permutation testing was applied with 10 000 permutations.29 All results were corrected for multiple comparisons using threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE)30 and p ≤ .05 family-wise error (FWE) rate, which is a conservative correction compared to other methods (e.g., false discovery rate or arbitrary uncorrected thresholds). Due to the exploratory character of the study, we additionally report p(FWE) ≤ .1 values (denoted as tendencies) to give a more comprehensive picture of the activation pattern and ensure a certain level of sensitivity while still being aware of the expected FWE-rate.31, 32 TFCE-corrected values of p(FWE) ≤ .1 lie roughly between puncorrected < .001 and puncorrected < .00001. We conducted whole-brain and small volume correction (SVC) analyses for a mTL region of interest (ROI) encompassing the hippocampus and the amygdala as defined in the Harvard-Oxford-Atlas because of the often low signal-to-noise ratio in this region.33-35 Furthermore, we analyzed anatomically defined mTL and functionally defined frontal ROIs, using the Mann–Whitney-U-test. Functionally defined frontal ROIs were used, as anatomical frontal ROIs did not cover functional activation well. We used meta-analytic maps from Neurosynth (neurosynth.org36) to generate functional frontal ROIs using the keywords: “pictures”, “face” and “words”. These maps are based on data of many studies and thus represent typical activations from thousands of individuals. To obtain symmetrical frontal ROIs, we swapped the extracted right FL activations (thresholded at pBonferroni = .05) to the left hemisphere. This resulted in two frontal clusters for scenes, referred to as orbitofrontal and inferior frontal cluster, one cluster for faces and one for words, see Figure 3C.

Additionally, we explored potential functional relevance of brain regions. Firstly, we compared normal and low performing FLE patients and controls to facilitate comparison with a previous study.8 Therefore, the group of patients was split according to their recognition accuracy in each modality. We used the 16th percentile of memory performance in controls as reference (see Figure 1). Phenotyping using neuropsychological testing results was only applicable for the delayed verbal recall (for which we investigated differences in word and scene encoding activation), because only three patients performed below 16th percentile in verbal learning. Secondly, we examined correlations of brain activation and recognition accuracy and VLMT scores in patients and controls. Design learning scores did not correlate with scene, face or word recognition accuracy in either FLE patients or controls. Thus, we suppose design learning to be a distinct subfunction of nonvisual memory compared to scene and face recognition, which might be due to the differences in stimulus material, retrieval type (recall vs. recognition), or time of retrieval. Therefore, we concluded that the correlation of design learning scores with scene, face or word encoding activation would not be meaningful.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Behavioral data

FLE patients had significantly lower percentage of hits and recognition accuracy for words, a lower percentage of hits for scenes and in tendency a lower face recognition accuracy. The percentage of hits, false alarms, the recognition accuracy and the response bias are detailed in Table S2. The recognition accuracy is further depicted in Figure 1A. Further, FLE patients scored worse than controls in delayed verbal recall and design learning (Figure 1B, Table S3). An explorative comparison of lFLE and rFLE revealed no significant difference in memory performance. The percentage of impaired patients according to the 16th percentile criterion were: scene recognition 46%, face recognition 29%, word recognition 41%, verbal learning 12.5%, delayed verbal recall 25%, design learning 37.5%. χ2 test indicated no impact of laterality.

3.2 mTL volumes

Left hippocampal volumes of FLE patients (Mdn = 0.27, range: 0.23–0.33) were significantly larger than controls' (Mdn = 0.26, range: 0.22–0.32, U = 231.0, p = .03, d = 0.64). No further significant differences between FLE patients and controls were observed, see Figure 2. We explored memory performance in FLE subgroups with normal and high hippocampal volumes. For the left hippocampus, no difference occurred. Patients with high right hippocampal volume had significantly lower word recognition accuracy (Mdn = 28.5, range: 12.5–58.3) and in tendency lower design learning scores (Mdn = −0.66, range: −1.61–1.04) than patients with normal right hippocampal volume (word recognition: Mdn = 47.2, range: 25.7–68.7, U = 22.0, p = .01, d = 1.28; design learning: Mdn = 0.61, range: −1.57–1.72, U = 41.5, p = .08, d = 0.77). In correlation analyses higher left (rSpearman (22)= − .34, p = .10) and right hippocampal volumes (rSpearman (22)= − .34, p = .11) tended to correlate with worse design learning scores in FLE patients. In controls, by contrast, higher bilateral hippocampal volumes were associated with better verbal learning (left hippocampus: rSpearman (28) = .37, p = .04; right hippocampus rSpearman (28) = .52, p = .003) and delayed verbal recall scores (left hippocampus: rSpearman (28) = .32, p = .09; right hippocampus rSpearman (28) = .43, p = .02) and higher right hippocampal volumes were in tendency associated with better word recognition (rSpearman (28) = .30, p = .08). These correlation coefficients in controls differed significantly from FLE patients', whose correlations were consistently negative.

3.3 Memory fMRI activation

Figure 3A illustrates encoding activation of FLE patients and controls. Across stimulus types, FLE patients' encoding activation encompassed widespread bilateral temporal, basal ganglia, and occipital activations, which were largest during scene encoding. During word encoding, overall activation appeared more left-lateralized with additional left frontal activation.

In controls, functional activation differed descriptively from patients especially regarding the FL. During scene and face encoding controls additionally exhibited clusters of frontal activation, and during word encoding frontal activation was more widespread (Figure 3).

3.4 Between-group comparison

The statistical comparison of encoding activation between FLE patients and controls is detailed in Figure 3B,C and Table S4. Groups did not differ significantly during scene encoding. During face encoding, FLE patients exhibited significantly less activation than controls in the right anterior mTL. This was replicated only for the subsample of rFLE patients, suggesting that rFLE patients drove this effect. lFLE patients instead had reduced activation in bilateral occipital regions. Furthermore, FLE patients tended to have decreased activation in the right frontal ROI. During word encoding, only rFLE patients tended to have decreased activation in the left mTL ROI. Moreover, FLE patients demonstrated stronger activation than controls in the cingulate gyrus and in tendency in the right postcentral and opercular regions.

3.5 Normal- versus low-performing FLE patients and controls

Figure 4 and Table S4 depict the group comparisons of normal- versus low-performing FLE patients versus controls.

For face encoding, patients with normal face recognition exhibited lower right mTL activation than controls. For scene encoding and in tendency also for word encoding, only patients with impaired recognition accuracy had less mTL, occipital and (inferior) frontal ROI activation than controls. Those were right-sided for scenes and left-sided for words. Similarly, when phenotyping according to delayed verbal recall, impaired patients tended to have less activation in the right orbitofrontal ROI during scene encoding.

When phenotyping according to delayed verbal recall, normal compared to low performing patients, exhibited higher left frontal ROI activation during word encoding and higher right orbitofrontal ROI activation during scene encoding. Likewise, when phenotyping using the respective recognition accuracy, they had increased activation in the left and in tendency right frontal ROI during word and in tendency also in the right inferior frontal ROI during scene encoding. During word encoding normal performing patients further exhibited stronger right mTL ROI, right basal ganglia and left occipital activation and during scene encoding stronger right mTL and in tendency occipital activation.

Finally, in some regions, normal performing patients tended to show more activation than controls. For scene encoding and scene recognition, this increase encompassed left occipital regions. For word encoding and word recognition, increases were found in the right amygdala, which replicated when phenotyping according to delayed verbal recall, and the right frontal ROI.

We further explored which demographical and clinical characteristics in FLE patients might impact memory performance. Therefore, we compared normal and low performing groups regarding these features (see Table S7), which indicated that patients performing low in scene recognition had earlier epilepsy onset and longer epilepsy duration and in tendency a higher drug load.

3.6 Correlation analyses

We also calculated correlations of fMRI activation and memory scores for FLE patients and controls (see Supplementary Information IV in the Appendix S1).

In FLE patients, bilaterally increased scene encoding activation in mesial temporal, lateral temporal, basal ganglia, parietal and occipital regions was associated with better scene recognition. Correlations in the word condition were less widespread, more left-lateralized, and additionally included frontal regions. Correlations encompassed predominantly bilateral frontal regions and basal ganglia, and left lateral temporal, parietal and occipital regions. At a lower threshold, correlations were more bilateral and partly extended into hippocampus and amygdala (p(FWE) ≤ .1). Furthermore, verbal learning scores positively correlated with scene encoding activation in predominantly right frontal regions. We found no significant correlation for face encoding, which might be due to the reduced variance with predominantly low memory performance for faces.

4 DISCUSSION

This study compared the memory performance, mTL volumes and fMRI encoding activation in predominantly lesional presurgical FLE patients and controls. We used various materials and related memory performance to mTL structures and to fMRI activity during encoding. Results indicated that at least pharmacoresistant FLE affects memory performance and the functional and structural integrity of the mTL, besides causing functional changes in the FL itself.

4.1 Behavioral results

FLE patients had worse verbal and nonverbal memory performance than controls. This is in line with recent literature on memory impairment in FLE patients.8, 3, 37, 38 Further, verbal memory scores suggested that patients are not impaired in verbal learning but have a consolidation or long-term retrieval deficit. However, the fMRI data indicated further abnormalities during encoding itself (see below). We suppose that memory impairments reflect contributions of the FL to memory as well as rapid seizure propagation from the frontal to the temporal lobe.39, 40 In a similar vein, TLE patients have been reported to have executive impairments due to seizure propagation which improve after epilepsy surgery.41 As expected and supported by previous studies,42, 8, 37 we did not find behavioral effects of FLE lateralization, although interpretation is limited by the small and unequal sub-samples. Notably, verbal memory deficits were consistently observed although our sample consisted mainly of rFLE. This accords with FLE resulting in network disruptions rather than disruptions of only focal brain regions.

4.2 Structural mTL changes

Left hippocampal volumes were generally larger in FLE patients than in controls. Centeno et al.9 also reported increased mTL volumes in FLE patients, namely in the piriform cortex, amygdalae and parahippocampal gyrus bilaterally, but not in the hippocampus. Other studies did not find abnormal mTL volumes in FLE12, 13, 8 which might be due to specific sample characteristics. Given that our patients were recruited during presurgical evaluation and mostly had established lesions, they might have been more severely ill and in some respects more homogeneous than other samples. The neurobiological cause of volume increases is still debated. They could reflect diminished gray and white matter demarcation due to nonatrophic histopathological abnormalities.43 Volume increases have also been linked to reorganization.44 However, the hippocampal volume increase in FLE seemed to be functionally irrelevant or even dysfunctional according to correlational analysis, whereas in controls larger volumes were correlated with better performance. A similar finding exists for children with FLE.45 Here, higher right amygdala, cuneus and occipital cortex volumes were reported in children with impaired compared to unimpaired cognitive performance. These volume increases were suggested to reflect disturbed maturation or inefficient compensatory mechanisms in terms of synaptic sprouting secondary to reduced functional inputs to these brain regions.

4.3 Neural correlates of encoding

Encoding activations in FLE patients and controls were widespread. Descriptively, FLE patients exhibited lower frontal activation in all three conditions than controls. Although this observation contradicts a previous finding,8 it is rather intuitive that the FL is less activated by cognitive tasks in patients with epileptic activity and structural lesions in the FL. This systemic impact of FLE is also found in other fMRI-tasks assessing executive functions46 or emotion regulation.47 In our sample, 91.7% of patients had structural lesions whereas this was the case in only 25% in Centeno et al.,8 which might account for the more severe disruption of task-induced FL recruitment in our patients. Additionally, here, more patients (up to 46%, depending on the material) had impaired memory compared with 22% in Centeno et al.8

Group comparisons revealed significant encoding-related differences primarily in the mTL. During face encoding FLE patients had less activation in the right anterior mTL, for which explorative analysis of sub-samples suggests it might be driven by rFLE patients. Centeno and colleagues did not report generally reduced mTL activation, at least when comparing mostly nonlesional patients and controls and collapsing across various encoding materials. Instead, a reduction occurred only in their group of low performing patients. Hence, reduced mTL activation might be more common in patients with known structural lesions. It might also be driven by rFLE patients and the face encoding task as previous studies indicated that the right FL and mTL are typically more activated than the left during face encoding.17, 33, 8 Further, inspection of t-values in controls indicated that both right anterior mTL and right FL activation were stronger during face than during scene or word encoding. Because stronger activation generally increases the possibility to identify between-group differences, this might have facilitated finding group differences in these regions during face encoding. For face recognition, the comparison of normal and low performing FLE patients revealed no difference in mTL or FL activation. However, due to the low variance of face recognition accuracy, the division of normal and low performers could have been less valid than for other materials. When instead splitting the groups according to median split, ROI analysis showed reduced right mTL and in tendency also right frontal activation only in low performing FLE patients compared to controls.

For scene and for word encoding, we found reduced mTL and FL activation in low performing FLE patients compared with normal performing FLE patients and partly also compared with controls. Clinically, impaired scene recognition was associated with earlier epilepsy onset and longer epilepsy duration. There were hints towards compensatory activation, too: correlation analysis associated higher verbal memory with increased right frontal activation only in FLE patients but not in controls. Reduced mTL activation in low performing FLE patients is in line with previous across-material results.8 For normal performing patients, Centeno et al. reported bilaterally increased FL activation. Our analysis revealed a more specific pattern: In particular, word processing was more bilateral in our normal performing FLE patients, which might reflect reorganization. Hence, memory impairment in FLE seems due to functional changes in the mTL besides the influence of the FL itself.

During word encoding, FLE patients had higher activation than controls especially in the posterior cingulate gyrus. As the overall contrast showed less activation during encoding than during baseline in this region, these activation increases in patients might reflect less deactivation compared with controls. In our previous study TLE patients also exhibited less deactivation than controls in regions which are part of the default mode network.17 This finding is reminiscent of an fMRI study on expressive language and working memory.46 The study reported for FLE and TLE patients alike reduced deactivation in the default mode network. Together, recent findings indicate that less deactivation in regions, which are part of the default mode network, might be common to different types of focal epilepsies across various tasks.

4.4 Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first one comparing material-specific encoding activation between FLE patients and controls. All patients were undergoing presurgical evaluation and the vast majority had a specific FL lesion. This increases the specificity of the findings, but may reduce the generalizability across FLE. Although we analyzed a sample size within the range of similar studies, we could address effects of FLE lateralization only exploratively and could not distinguish between different FL localizations. Also, the impact of clinical and demographical characteristics (e.g. etiology, language lateralization, antiseizure medication, education) could only be addressed in a preliminary way. Therefore, future studies should extend and confirm our results in larger samples.

5 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Our study underlines the material-specific impact of FLE on core mTL memory regions, besides the FL itself. FLE patients’ memory impairment might originate not only from frontal changes but also from functional and possibly even structural changes in the mTL, underscoring the functional importance of bidirectionally connected fronto-temporal networks. Present results are most representative of presurgical FLE patients. Future work will determine whether they generalize to less chronic patients, are reversible by lesion resection, and specify effects of lesion laterality or locus on functional and structural changes. Further, comparison with data from other epilepsy types will help delineate the specificity of results and gauge effects of antiseizure medication. Comparison with our previous study17 indicates less severe memory deficits in FLE than TLE and somewhat different underlying activation patterns. Due to space limitations, the direct comparison will be presented elsewhere.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (LA 3567/2-1 and BI 1254/9-1). We thank the study participants for their patience and cooperation. We further thank Simon Laumen, Stefanie Germer, Anissa Benzait, Anke Diekmann, and Markus Mertens for their support with data collection. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All unthresholded statistical fMRI maps are available on NeuroVault (https://identifiers.org/neurovault.collection:14528). Additional data from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.