Successful epilepsy surgery in two cases with multiple sclerosis

This work has not been presented at meetings.

Abstract

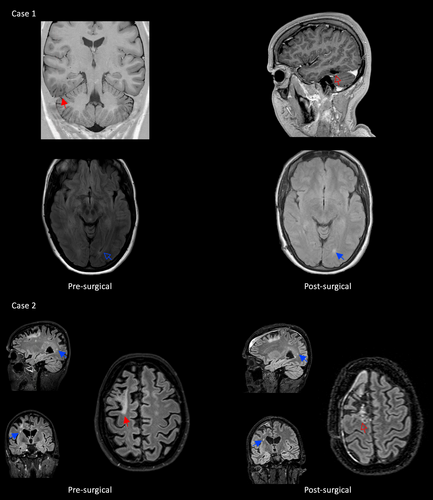

Brain surgery is the only curative treatment for people with focal epilepsy, but it is unclear whether this induces active disease in multiple sclerosis (MS). This creates a barrier to evaluate MS patients for epilepsy surgery. We present two cases of successful epilepsy surgery in patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy and stable MS and give an overview of the existing literature. (1) a 28-year-old woman with seizures arising from a right basal temporo-occipital ganglioglioma was seizure-free after surgery, without MS relapse but with one new MS lesion postsurgically. (2) a 46-year-old woman with seizures arising from a natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) lesion in the right frontal lobe was seizure-free after surgery preceded by extraoperative subdural electrocorticography, with new subclinical MS lesions. We are the first to report brain surgery in a PML survivor. Both patients stabilized radiologically after initiating second-line therapies. Successful epilepsy surgery can substantially increase the quality of life in patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy and MS. With increasing survival rates of brain tumors and PML, the risk–benefit ratio of epilepsy surgery compared to a potential MS relapse after surgery becomes critically important. Shared decision-making is valuable for balancing the risks related to both diseases.

1 INTRODUCTION

Most seizures in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) are related to an MS relapse, but the prevalence of chronic epilepsy in people with MS is higher than in the general population.1 White matter lesions in MS are most prominent in neuroimaging, but gray matter can also be affected.2 Gray matter lesions and a progressive disease course with high lesion load are risk factors for chronic epilepsy.3 The majority of people with MS and active epilepsy suffer from focal seizures and are treated with antiseizure medication (ASM). Epilepsy surgery is a curative treatment option for people with focal epilepsy, but both physical trauma and psychological stress can be triggers for MS exacerbations,4 which creates a barrier to evaluate MS patients for epilepsy surgery. Literature on this topic is scarce, which makes the decision to perform surgery even harder.

We present two cases of successful epilepsy surgery in patients with stable relapsing-remitting MS who were treated in The Netherlands over the last years. We also give an overview of the existing literature in the Discussion. Both patients provided informed consent for publishing of this article.

2 CASE 1

The first case is a woman with seizures since early adulthood, that start with staring, automatisms of the right hand, oral automatisms, and decreased attention. She had one seizure per month and was treated with carbamazepine 800 mg/day since 3 years and clobazam 20 mg/day since 2 years and had tried valproic acid and levetiracetam before. Video-EEG interictal and ictal findings showed a right temporo-occipital focus. 3 T brain MRI showed a long-term epilepsy-associated tumor (LEAT) right basal temporo-occipital (Figure 1). Multiple T2 hyperintensities were visible in the white matter. She was diagnosed with remitting–relapsing MS at the age of 25 after transient left leg sensory symptoms followed by transient dizziness, combined with the hyperintensities on MRI. Dimethyl fumarate was initiated. She was evaluated for epilepsy surgery at the age of 28, because of the restrictions she felt from both diseases. She agreed to a resection of the temporo-occipital lesion under intraoperative electrocorticography (ECoG), assuming that the lesion on MRI was the responsible epileptogenic zone. The patient was counseled that a MS exacerbation could be a postoperative consequence. A baseline MRI with MS protocol was performed just before surgery. Intraoperative ECoG demonstrated spikes, which were absent after extensive lesionectomy. Pathological examination showed a ganglioglioma WHO grade 1 (no 1p/19q codeletion, no IDH1/2 mutation, no MGMT methylation, no BRAF V600E mutation). She had an uneventful recovery without MS exacerbations and has been seizure-free (ILAE 1) 54 months after surgery with all ASM stopped. A small tumor remnant remained stable on annual radiological follow-up, and a new, asymptomatic, radiological MS lesion was found 1 year after surgery. Natalizumab was started, followed by radiological stability.

3 CASE 2

The second case is an adult who was diagnosed with MS in her late thirties because of problems with walking. After 3 years with progressive symptoms, she started natalizumab. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) was diagnosed 1 year later (Figure 1). Natalizumab was discontinued and the patient received plasmapheresis treatment.5 The first seizure was 2 years after the diagnosis of PML, with a feeling in the head, “floating” of thoughts, followed by loss of awareness and unresponsiveness, freezing, and an eye deviation toward the left. The patient wanted epilepsy surgery 3 years later, because she “suffered bouts of MS and PML, but having seizures is far worse.” She had one seizure per week and was treated with lacosamide 400 mg/day and lamotrigine 200 mg/day for more than 2 years and tried valproic acid before. MRI showed predominantly right-sided white matter abnormalities and a PML atrophic lesion in the right frontal lobe with gliosis reaching the cortical surface. Video-EEG showed right frontal seizure onset. The patient motivated the wish for epilepsy surgery as “I suffered bouts of MS and PML, but having seizures is far worse.” The treating MS neurologist (J.K.) supported surgery based on the experience that in case of a possible increase of MS disease activity after surgery, alternative immunomodulation treatments were available.6 Intracranial EEG was advised to pinpoint the focus and limit the extent of surgery. Subdural EEG revealed seizure onset in the right supplementary motor area (SMA), which was resected. The postoperative SMA function loss, with hemiparesis of the left arm and leg, was anticipated. This is usually temporary,7 but in this case, residual motor problems on the left still exist 2 years after surgery, though she improved. The patient is seizure-free (ILAE 1) with unchanged ASM. Follow-up MRIs showed new MS lesions 1.5 years after surgery. Medication switched from dimethyl fumarate to anti-B-cell therapy, followed by radiological stability. She is extremely happy with the result and life without seizures.

4 DISCUSSION

Decisions to pursue epilepsy surgery in MS are hampered by scarce knowledge of the risk of MS deterioration.

We searched PubMed on April 8, 2022 for “Multiple Sclerosis [MeSH Terms] AND Epilepsies, Partial [Mesh Terms] AND surgery”, which gave 10 results. After abstract screening, three papers addressed epilepsy surgery in people with MS. One case report describes successful epilepsy surgery of the anterior temporal lobe with hippocampectomy with a plaque in the anterior parahippocampal gyrus. This patient was seizure-free without postoperative complications, but new plaques appeared on MRI in both frontal lobes.8 Another case report describes resection of a temporal lobe cavernoma resulting in seizure freedom, with postoperative progression of MS with new lesions in the contralateral hemisphere. This patient had several relapses with progressive neurological deterioration in the first year after surgery.9 A third paper reports a diagnosis of MS 3 months after epilepsy surgery for left hippocampal sclerosis, suggesting that the surgery might have provoked clinical manifestations of MS.10 Deterioration of MS is also seen in nonbrain surgery in 14% of MS patients, indicating that other factors associated with surgery (anesthesia, physical trauma, recovery) might play a role.4 Both our patients showed new plaques postoperatively, far from the surgical location, without clinical symptoms. Presurgical MRI with MS protocol just before surgery can be used as baseline.

Our first patient had a ganglioglioma that caused the seizures. People with MS seem to have an increased risk for brain tumors,11 but it is unclear if this is related to the increased level of glial cell reactivity in MS, to immunosuppressive therapy, or increased detection with increased neuroimaging.12 Mandel et al. also report one case with ganglioglioma and MS, without epilepsy, who underwent surgery with unknown outcome.13 Hofer et al. report six patients with high-grade brain tumors without clinical MS deterioration after surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, but MRI findings are not reported.14 Sirko et al. report a high-grade tumor case without clinical and radiological MS deterioration after surgery.12 The potential relapse of MS in case of high-grade brain tumors might be less important in the decision to perform brain surgery compared to low-grade tumors or epilepsy surgery. However, chronic epileptic seizures play an important role in the quality of life in patients with low-grade tumors and increase disease-associated mortality. Therefore shared decision-making is important in these patients for balancing the risk–benefit ratio related to both diseases.

Our second patient survived natalizumab-associated PML. The prevalence of seizures in PML is higher than in the general population, and also higher than in people with MS (18% vs. 2.3%). The risk of seizures is especially high when the PML lesions are adjacent to cortex.15 To our knowledge, there is no literature on brain surgery in people who survived PML. One of the concerns is the reactivation of the John-Cunningham (JC) virus by the surgery, although PML does usually not reoccur. We performed extraoperative intracranial electrocorticography without complications. We opted for subdural grid recordings because we hesitated to penetrate the brain with stereo-EEG electrodes. This patient had persistent motor problems after resection in the right SMA, although she improved and regained independent walking and cycling. SMA removal hemiparesis is usually temporary,7 we hypothesize that the brain's recovery mechanisms in MS are impaired.

5 CONCLUSION

We show that epilepsy surgery can be successful in patients with stable MS. Both our cases had seizures originating from lesions other than classic MS plaques. Our patients' MS remained clinically stable after surgery and stabilized radiologically after initiating second-line disease-modifying therapy. Since anecdotal cases of MS relapses have also been reported, the risk–benefit ratio cannot be adequately estimated with the current small number of reported patients. The unique characteristics of these patients and their personal preferences necessitate a tailor-made approach. This report shows that epilepsy surgery can be a valuable treatment option, also in people with MS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nicole van Klink: draft and revision of manuscript, study concept, data interpretation. Simon Tousseyn: draft and revision of manuscript, data acquisition, data interpretation. Pieter van Eijsden: revision of manuscript, data acquisition, data interpretation. Pieter Vos: revision of manuscript, data acquisition, data interpretation. Danny Hilkman: revision of manuscript, data acquisition, data interpretation. Joep Killestein: revision of manuscript, data acquisition, data interpretation. Frans Leijten: draft and revision of manuscript, study concept, data interpretation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was written on behalf of the regional epilepsy surgery taskforces (AWEC/USWEC).

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was not funded.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

F. Leijten holds shares in ProLira, a company that manufactures DeltaScan, an EEG-based delirium detection device; he is unpaid consultant for LivAssured, a company that manufactures NightWatch, a device for nocturnal seizure alarming. J. Killestein received consulting fees of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Biogen, Teva, Merck, Novartis, Immunic, Celgene, and Sanofi/Genzyme (all payments to institution); reports speaker relationships with F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Biogen, Celgene, Teva, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi/Genzyme (all payments to institution). The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Both patients provided informed consent for publishing of this article.

REFERENCES

Test Yourself

-

How many people with multiple sclerosis have seizures?

- 0.5%–1%

- 1%–2%

- 2%–3%

- 3%–4%

- 4%–5%

-

What is the most common type of seizures in multiple sclerosis?

- Focal seizures

- Generalized seizures

-

How many people progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy have seizures?

- 0.5%–5%

- 5%–10%

- 10%–15%

- 15%–20%

- 20%–25%

Answers may be found in the supporting information.