Twenty-four-hour heart rate lowering with ivabradine in chronic heart failure: insights from the SHIFT Holter substudy

Abstract

Aims

Analysis of 24-h Holter recordings was a pre-specified substudy of SHIFT (Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial) for exploring the heart rhythm safety of ivabradine and to determine effects of ivabradine on 24-h, daytime, and night-time heart rate (HR) compared with resting office HR.

Methods and results

The 24-h Holter monitoring was performed at baseline and 8 months after randomization to ivabradine (n = 298) or matching placebo (n = 304) titrated maximally to 7.5 mg b.i.d. in patients with baseline HR ≥70 b.p.m. Patients received guideline-based optimized heart failure therapy including ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs in 93% and beta-blockers at maximally tolerated doses in 93%. After 8 months, HR over 24 h decreased by 9.5 ± 10.0 b.p.m. with ivabradine, from 75.4 ± 10.3 b.p.m. (P < 0.0001), and by 1.2 ± 8.9 b.p.m. with placebo, from 74.8 ± 9.7 b.p.m. (P < 0.0001 for difference vs. ivabradine). HR reduction with ivabradine was similar in resting office and in 24-h, awake, and asleep recordings, with beneficial effects on HR variability and no meaningful increases in supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias. At 8 months, 21.3% on ivabradine vs. 8.5% on placebo had ≥1 episode of HR <40 b.p.m. (P < 0.0001). No episode of HR <30 b.p.m. was recorded; 3 (1.2%) patients had RR intervals >2.5 s on ivabradine vs. 4 (1.6%) patients on placebo. No RR intervals >3 s were identified in patients taking ivabradine.

Conclusion

Ivabradine safely and significantly lowers HR and improves HR variability in patients with systolic heart failure, without inducing significant bradycardia, ventricular arrhythmias, or supraventricular arrhythmias.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is associated with high 5-year mortality despite existing pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments.1, 2 HF also frequently causes hospitalization as the

condition worsens.3, 4 It is associated with an autonomic imbalance, specifically increased sympathetic activity, and reduced vagal activity, resulting in an increase in heart rate (HR) with reduced heart rate variability (HRV) parameters.5-7 An inverse relationship exists between HR and prognosis in patients with poor left ventricular (LV) systolic function, mainly because of worsening HF.8-10 With 24-h Holter monitoring (ambulatory ECG), night-time and daytime HRs are also associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes.11 In addition, a number of reports emphasize the role of the autonomic nervous system in triggering ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.12 HRV measurement provides non-invasive evaluation of autonomic function and enables prediction of cardiovascular events in patients who have had a myocardial infarction and in patients with depressed LV systolic function.6-8 Furthermore, pharmacological agents that improve outcome in patients with HF also improve HRV parameters.13-15

Ivabradine is a specific HR-slowing drug that acts by inhibiting the If current in the sinoatrial node. The drug has antianginal and anti-ischaemic properties in patients with stable angina.16, 17 However, its effects on night-time, daytime, and 24-h HR reduction are not known in HF. The SHIFT (Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial) was a large international clinical phase III trial that evaluated 6505 patients with moderate to severe HF, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%, and resting HR ≥70 b.p.m., randomized to ivabradine 5 mg b.i.d. (n = 3268) or placebo (n = 3290),18 with potential for titration up to 7.5 mg b.i.d. The SHIFT trial demonstrated that HR lowering using ivabradine on top of guideline-based background therapy resulted in a significant reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for worsening HF.

The aims of this prospective SHIFT substudy were two-fold: first, to evaluate the effect of ivabradine compared with placebo on HRV and safety parameters, including heart rate turbulence (HRT) since ivabradine prolongs sinus cycle length, measured on 24-h Holter ECG recordings; and, secondly, to detect symptomatic or asymptomatic conduction or rhythm disorders with ivabradine treatment, including RR interval prolongation, bradycardia, tachycardia, premature depolarization, atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation/flutter, and accelerated idioventricular rhythm.

Methods

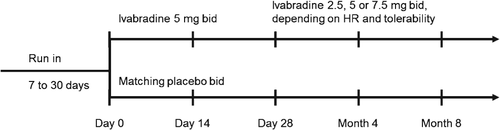

The design and main results of the SHIFT trial have been published elsewhere.18 Briefly, this was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel-group study in patients with systolic HF, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II, III, or IV symptoms, in a stable condition for ≥4 weeks, on guideline-based medical therapy with unchanged HF medications and doses for ≥4 weeks, and with a documented hospital admission for worsening HF within the previous 12 months. Patients had to be in ECG-documented sinus rhythm with resting HR ≥70 b.p.m. and LVEF ≤35% in the 3 months before inclusion. The study featured a pre-randomization interval of 14 days in which eligible patients were randomized to ivabradine or placebo. The post-randomization period included a titration opportunity, with a visit at 2 weeks and at 4 weeks, and a follow-up at 4 months after inclusion and then every 4 months. The starting dose was 5 mg (or matching placebo) twice daily; at day 14, ivabradine was up-titrated to 7.5 mg b.i.d. unless the resting HR was ≤60 b.p.m. If the HR was <50 b.p.m. or the patient was experiencing signs or symptoms related to bradycardia, the ivabradine dose was down-titrated to 2.5 mg (or matching placebo) twice daily (Figure 1).

For this Holter substudy, participating centres in the selected countries were chosen according to their ability to fulfil the substudy requirements. In these centres, all patients eligible for selection in the main study were asked to participate in the substudy and signed a written informed consent form specific to the Holter substudy in addition to the consent form for the main study. This substudy was approved by the relevant ethics committees and was intended to include ∼500 patients. It was conducted in 82 centres in 21 countries and was sponsored by the Institute de Recherches Internationales Servier (IRIS) and locally by Servier Canada Inc. The 24-h digital Holter monitoring (SEER® MC Ambulatory Digital Analysis Recorder, General Electric Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) was performed at baseline during the 24 h before randomization and at 8 months. Thus, the active double-blind treatment period for the substudy lasted 8 months (Figure 1).

Efficacy measurements

All Holter recordings were read centrally at the Montreal Heart Institute using the dedicated MARS ambulatory ECG analysis system (General Electric Healthcare). The readers were blinded to study treatment allocation and to temporal sequences of recording. The digitized Holter recordings were saved on compact flashcards and then analysed using standard reading software. HRV, including time domain and frequency domain parameters, was studied. The time domain measures included the standard deviation of all normal-to-normal RR intervals (in ms) recorded during 24 h (SDNN), the standard deviation of average normal-to-normal RR intervals of 5 min segments of the 24-h recording (SDANN), the root mean square of differences between successive normal-to-normal RR intervals (RMSSD), the number of interval differences of successive NN intervals >50 ms (NN50), and the percentage of interval differences of successive NN intervals >50 ms [PNN50 (NN50 divided by the total number of NN intervals)].

Frequency domain measures, based on a power spectral analysis, included the following. (i) TP = total power (ms2): variance of all NN intervals. (ii) ULF (ms2): power in the ultra-low frequency range (<0.003 Hz). (iii) VLF (ms2): power in the very low frequency range (0.003–0.04 Hz). (iv) LF (ms2): power in the low frequency range (0.04–0.15 Hz). (v) HF (ms2): power in the high frequency range (0.15–0.4 Hz). (vi) LF (n.u.): computed as LF/(TP – VLF). (vii) HF (n.u.): computed as HF/(TP – VLF). (viii) LF/HF (ratio): computed as LF/HF.

Heart rate turbulence defined as a biphasic, acceleration–deceleration response of the sinus node triggered by a ventricular extrasystole, was also assessed with 24-h Holter monitoring. Turbulence onset (%) and the turbulence slope (ms per RR interval) were determined.

Safety measurements

Episodes of bradycardia (HR <50 b.p.m.), graded by severity (<50–40 b.p.m., <40–30 b.p.m., and <30 b.p.m), and RR interval pauses (>2, >2.5, and >3 s) were recorded at baseline and 8 months in the ivabradine and placebo groups. Cardiac rhythm disturbances—premature ventricular or supraventricular depolarization, ventricular tachycardia (VT), supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation or flutter [irregular RR intervals with no preceding P waves (or with atrial flutter waves) with atrial rate >220 b.p.m.], accelerated idioventricular rhythm (≥3 consecutive premature ventricular depolarizations with a rate <100 b.p.m.), and atrioventricular block—were also recorded in both groups at baseline and 8 months. Sustained tachycardia was defined as tachycardia lasting ≥30 s. Premature ventricular depolarization was characterized by premature beats with wide and aberrant QRS morphology and no preceding P wave. Premature supraventricular depolarization was characterized by premature beats with normal QRS morphology and duration. Atrioventricular block was classified as second-degree Mobitz I or II, third-degree, or high-degree block.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables have been summarized using mean (standard deviation) and categorical variables as number (percentage) of patients within each level. HRV and HRT parameters were assessed for all patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had a 24-h Holter monitoring of sufficient quality for analysis at baseline and at 8 months. Changes in parameters from baseline to 8 months were analysed. Treatment effects (ivabradine–placebo) and 95% confidence intervals were estimated from mixed regression models, adjusting for country as a random factor, beta-blocker intake at randomization as a fixed factor, and baseline value as a covariate. Within-group comparisons were also extracted from these models. Differences between groups in terms of proportions were tested using χ2 tests. Since this substudy was an exploratory study, no formal sample size calculation was performed.

Results

Patient characteristics

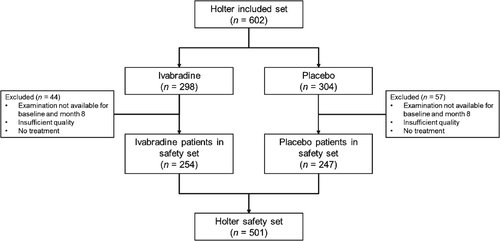

The SHIFT Holter substudy included 602 patients, 9.3% of the 6505 patients evaluated in the main study, with a balanced distribution in both groups, i.e. 298 patients in the ivabradine group and 304 patients in the placebo group (Figure 2). As shown in Table 1, the mean age of included patients was 59.4 ± 10.8 years, most of whom were male. The mean LVEF was 28.2 ± 5.5%; few patients (<1%) were in NYHA functional class IV and just over half (54%) were in class III. Ischaemic heart disease was the main cause for HF in two-thirds of patients. There were no significant differences between the two groups. It is noteworthy that the comparison between the baseline characteristics of the main SHIFT study and the present substudy showed no major differences except for antialdosterone medications (60% vs. 72%) and digitalis (22% vs. 32%), which were prescribed more often in the substudy. There were no significant differences between the two groups in device therapy (2.0% in the ivabradine group vs. 3.3% in the placebo group). The dose of ivabradine used at inclusion was up-titrated to 7.5 mg b.i.d. in most patients.

| Ivabradine (n = 298) | Placebo (n = 304) | All (n = 602) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.1 ± 10.7 | 58.6 ± 10.8 | 59.4 ± 10.8 |

| Male | 242 (81.2%) | 248 (81.6%) | 490 (81.4%) |

| Current smoker | 46 (15.4%) | 40 (13.2%) | 86 (14.3%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.0 ± 4.6 | 27.9 ± 5.0 | 27.9 ± 4.8 |

| (17.8; 46.3) | (17.4; 51.8) | (17.4; 51.8) | |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Sitting SBP (mmHg) | 121.5 ± 15.5 | 119.5 ± 15.1 | 120.5 ± 15.3 |

| (87; 172) | (88; 160) | (87; 172) | |

| Sitting DBP (mmHg) | 75.5 ± 9.2 | 75.6 ± 8.8 | 75.5 ± 9.0 |

| (42; 97) | (53; 100) | (42; 100) | |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 78.8 ± 9.0 | 78.8 ± 9.3 | 78.8 ± 9.2 |

| 76 (65; 116) | 75 (70; 120) | 76 (65 ; 120) | |

| <70 b.p.m. | 1 (0.3%) | – | 1 (0.3%) |

| ≥90 b.p.m. | 42 (14.1%) | 39 (12.8%) | 81 (13.5%) |

| Time since chronic HF diagnosis (years) | 3.4 ± 4.0 | 3.4 ± 4.6 | 3.4 ± 4.3 |

| 2.0 (0; 22) | 1.6 (0; 36) | 1.8 (0; 36) | |

| NYHA class | |||

| II | 138 (46.3%) | 136 (44.7%) | 274 (45.5%) |

| III | 159 (53.4%) | 165 (54.3%) | 324 (53.8%) |

| IV | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 4 (0.7%) |

| LVEF (%) | 28.2 ± 5.5 | 28.3 ± 5.4 | 28.2 ± 5.5 |

| 30 (10; 35) | 30 (10; 35) | 30 (10; 35) | |

| Ischaemic cause of HF | 202 (68.0%) | 201 (66.0%) | 403 (66.9%) |

- Values are presented as means ± standard deviations, numbers and percentages, or medians (minima; maxima).

- BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The Holter safety set included 501 patients (Figure 2). Most of the other patients excluded from the analysis (ivabradine arm n = 44, placebo arm n = 57) either did not receive at least one dose of study drug or had a Holter reading of insufficient quality at 8 months. Thus Holter recordings of 501 patients were included in the analyses.

Heart rate

In the safety set at baseline, mean HR with 24-h Holter monitoring was 75.2 ± 10.1 b.p.m. without significant differences between the two groups. Average 24-h HR was reduced by 9.5 ± 10.0 b.p.m. in the ivabradine group vs. 1.2 ± 8.9 b.p.m. in the placebo group (P < 0.0001). In both groups, HR reduction tended to be slightly greater during waking hours than during sleep, as shown in Table 2. Mean awake HR was similar to mean office HR at baseline (Table 3), but at 8 months office HR was significantly lower. Mean office HR was 9–10 b.p.m. higher than 24-h asleep HR with Holter monitoring in both groups at baseline. In the placebo group at baseline, mean office HR was 2.8 b.p.m. higher than mean 24-h HR with Holter monitoring (P < 0.0001) (Table 3). At 8 months, patients on ivabradine had more episodes of HR <40 b.p.m. than those on placebo (21.3% vs. 8.5%) (Table 4). These episodes occurred more frequently when patients were asleep (18.5% vs. 9.1% during the awake period in the ivabradine group; and 7.7% vs. 3.6% in the placebo group). No episodes below 30 b.p.m. were recorded. Three (1.2%) patients on ivabradine had RR intervals >2.5 s vs. 4 (1.6%) on placebo at 8 months (Table 4). No patient on ivabradine had RR intervals >3 s. No other abnormalities were observed in the ivabradine group.

| HR measurement | Group | n (missing) | Baseline (b.p.m.) | 8 months (b.p.m.) | Δ Baseline to 8 months | Effect (95% CI)a | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean office HR | Ivabradine | 234 (5) | 78.4 ± 8.3 | 64.2 ± 9.8 | −14.2 ± 10.8 | −7.6 (−9.4 to −5.8) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 226 (4) | 77.7 ± 8.3 | 71.5 ± 12.1 | −6.2 ± 10.7 | |||

| Mean 24-h HR | Ivabradine | 239 (0) | 75.4 ± 10.3 | 66.0 ± 9.7 | −9.5 ± 10.0 | −8.0 (−9.5 to −6.5) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 230 (0) | 74.8 ± 9.7 | 73.6 ± 10.6 | −1.2 ± 8.9 | |||

| Mean HR awake | Ivabradine | 238 (1) | 78.7 ± 11.0 | 69.0 ± 10.3 | −9.7 ± 10.5 | −8.3 (−10.0 to −6.7) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 229 (1) | 78.5 ± 10.4 | 77.2 ± 11.4 | −1.3 ± 9.9 | |||

| Mean HR asleep | Ivabradine | 238 (1) | 68.9 ± 10.2 | 59.9 ± 9.4 | −9.0 ± 10.0 | −7.5 (−9.0 to −5.9) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 229 (1) | 67.7 ± 9.8 | 66.8 ± 10.4 | −1.1 ± 8.7 |

- Heart rate reduction in the ivabradine group tended to be greater when patients were awake.

- Values are presented as numbers or means ± standard deviations.

- CI, confidence interval; HR, heart rate.

- a Treatment effect (ivabradine–placebo) estimated from linear model of change from baseline after adjusting for treatment, country, beta-blocker intake at randomization, and baseline value.

| HR comparison | Ivabradine | Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | HR difference (b.p.m.), 95% CI | P-value | n | HR difference (b.p.m.), 95% CI | P-value | |

| Baseline | ||||||

| Mean office HR vs. mean 24-h HR | 234 | 2.9 (1.7 to 4.1) | <0.0001 | 226 | 2.8 (1.6 to 4.0) | <0.0001 |

| Mean office HR vs. mean 24-h awake HR | 233 | −0.4 (−1.7 to 0.9) | 0.53 | 225 | −0.9 (−2.2 to 0.4) | 0.19 |

| Mean office HR vs. mean 24-h asleep HR | 233 | 9.4 (8.3 to 10.6) | <0.0001 | 225 | 9.9 (8.6 to 11.1) | <0.0001 |

| 8 months | ||||||

| Mean office HR vs. mean 24-h HR | 234 | −1.4 (−2.4 to −0.4) | 0.0055 | 226 | −2.2 (−3.4 to −1.0) | 0.0002 |

| Mean office HR vs. mean 24-h awake HR | 234 | −4.4 (−5.5 to −3.4) | <0.0001 | 226 | −5.8 (−7.0 to −4.6) | <0.0001 |

| Mean office HR vs. mean 24-h asleep HR | 234 | 4.7 (3.7 to 5.7) | <0.0001 | 225 | 4.7 (3.6 to 5.8) | <0.0001 |

- CI, confidence interval; HR, heart rate.

| n | Low HR events (b.p.m.) | RR interval pauses | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR ≥50 | 50 < HR ≤40 | 40 < HR ≤30 | HR <30 | P-valuea | >2 s | >2.5 s | >3 s | ||

| Baseline | |||||||||

| Ivabradine | 254 | 143 (59.8%) | 88 (36.8%) | 7 (2.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.3409 | 7 (2.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | – |

| Placebo | 247 | 129 (56.1%) | 88 (38.3%) | 13 (5.7%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (4.8%) | 2 (0.9%) | – | |

| 8 months | |||||||||

| Ivabradine | 254 | 63 (24.8%) | 137 (53.9%) | 54 (21.3%) | 0 (0%) | <0.0001 | 22 (8.7%) | 3 (1.2%) | – |

| Placebo | 247 | 128 (51.8%) | 98 (39.7%) | 21 (8.5%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (3.6%) | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

- As expected, more episodes of bradycardia with heart rate (HR) <40 b.p.m. and pauses where RR was >2 s occurred in the ivabradine group than in the placebo group at 8 months. It should, however, be noted that no episodes with HR <30 b.p.m. occurred with ivabradine and that there was no difference between the two groups as regards pauses with RR >2.5 s.

- Values are presented as numbers and percentages.

- a Comparison of the distribution across treatment groups.

Holter abnormalities

The percentage of patients with at least one episode of supraventricular tachycardia at 8 months was not significantly higher (43.7%) in the ivabradine group than in the placebo group (41.3%) (P = 0.59) (Table 5). Except for two patients (0.8%) in the ivabradine group, supraventricular tachycardia was non-sustained at 8 months. Patients with non-sustained VT at 8 months were less frequent in the ivabradine group (28.3%) than in the placebo group (33.2%) (P = 0.24). No sustained VT was reported at 8 months. Atrial fibrillation was found in 6 patients (2.4%) in the ivabradine group and in 5 patients (2.0%) in the placebo group at 8 months (P = 0.80). Accelerated idioventricular rhythm was found at 8 months in 22.1% of the ivabradine group and in 19.8% of the placebo group (P = 0.54), similar to the frequencies observed in the baseline recordings (20.1% vs. 19.1%). As regards emergent atrioventricular block over 24 h, no relevant difference between the ivabradine and placebo groups was observed for second-degree Mobitz I (1.2% vs. 2.4%) or Mobitz II (0.4% vs. 1.6%) block. No patient experienced third-degree block, and one patient from each group experienced emergent high-degree block. The numbers of ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias were low and are summarized in Table 5.

| Safety parameters | Ivabradine | Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8 months | Δ 8 M–Ba | Baseline | 8 months | Δ 8 M–Ba | |

| Premature ventricular depolarizations (per h) | ||||||

| Mean | 76 ± 169 | 78 ± 187 | 2.1 ± 170 | 87 ± 359 | 69 ± 151 | −18 ± 366 |

| Median | 15 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 10 | 0 |

| Premature supraventricular depolarizations (per h) | ||||||

| Mean | 29 ± 128 | 37 ± 143 | 7.7 ± 81 | 28 ± 95 | 15 ± 56 | −12 ± 91 |

| Median | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Ventricular tachycardia (over 24 h) | ||||||

| No episode | 148 (58.3%) | 182 (71.7%) | 151 (61.1%) | 165 (66.8%) | ||

| ≥1 episode | 91 (38.1%) | 72 (28.3%) | 79 (34.3%) | 82 (33.2%) | ||

| ≥1 sustained | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| ≥1 polymorphic | 35 (14.6%) | 28 (11.0%) | 31 (13.5%) | 24 (9.7%) | ||

| Supraventricular tachycardia (over 24 h) | ||||||

| No episode | 138 (54.3%) | 143 (56.3%) | 132 (53.4%) | 145 (58.7%) | ||

| ≥1 episode | 101 (42.3%) | 111 (43.7%) | 98 (42.6%) | 102 (41.3%) | ||

| ≥1 sustained | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.8%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (over 24 h) | ||||||

| Change in no. of episodes | 2 ± 6 | 2 ± 8 | −0.08 ± 7 | 5 ± 28 | 5 ± 40 | 1.25 ± 47 |

| No. of beats in the longest episode | 6.6 ± 5.0 | 6.6 ± 5.0 | 7.2 ± 7.7 | 6.0 ± 3.9 | ||

| Highest HR during episodes (b.p.m.) | 142.5 ± 27.1 | 138.4 ± 27.3 | 144.7 ± 29.4 | 141.5 ± 27.1 | ||

| Non-sustained supraventricular tachycardia (over 24 h) | ||||||

| Change in no. of episodes | 7 ± 51 | 12 ± 91 | 5 ± 87 | 4 ± 27 | 3 ± 14 | −2 ± 28 |

| No. of beats in longest episode | 12.2 ± 15.4 | 10.2 ± 13.8 | 9.2 ± 12.2 | 9.6 ± 13.1 | ||

| Highest HR during episodes (b.p.m.) | 136.7 ± 21.0 | 129.3 ± 20.4 | 132.7 ± 24.1 | 132.3 ± 20.3 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | ||||||

| No. of patients with ≥1 episode | 1 (0.4%) | 6 (2.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 5 (2.0%) | ||

| Highest HR during episodes (b.p.m.) | 152 | 181 ± 23 | 163 ± 33 | 136 ± 45 | ||

| Accelerated idioventricular rhythm(over 24 h) | ||||||

| Change in no. of episodes | 2 ± 7 | 16 ± 174 | 14 ± 173 | 1 ± 7 | 2 ± 13 | 1 ± 14 |

| Duration of longest episode (s) | 5.1 ± 6.6 | 5.6 ± 5.9 | 32.3 ± 181.6 | 5.7 ± 6.4 | ||

| HR of longest episode (b.p.m.) | 81.3 ± 13.0 | 79.1 ± 13.4 | 80.8 ± 13.4 | 80.0 ± 12.9 | ||

| Atrioventricular block (over 24 h) | ||||||

| Second degree (Mobitz I) | 4 (1.7%) | 3 (1.2%) | 5 (2.2%) | 6 (2.4%) | ||

| Second degree (Mobitz II) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 4 (1.6%) | ||

| Third degree | – | – | 1 (0.4%) | – | ||

| High degree | – | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

- Values presented are means ± standard deviations, numbers and percentages, or medians.

- HR, heart rate.

- a Change from 8 months to baseline.

Heart rate variability

Comparing baseline recordings with those at 8 months, all time domain parameters (SDNN, SDANN, RMSSD, NN50, and PNN50) increased significantly in the ivabradine group whereas no change occurred in the placebo group (Table 6). The frequency domain parameters also increased significantly in the ivabradine group, but remained unchanged in the placebo group. HRT onset did not change over time, whereas mean turbulence slope tended to increase in the ivabradine group. At 8 months, the percentage of patients with normal turbulence onset and turbulence slope was not significantly higher in the ivabradine group than in the placebo group (43% vs. 38%, respectively; P = 0.41); the reverse trend, although non-significant, was observed at baseline (38% in the ivabradine group vs. 44% in the placebo group, P = 0.66). Turbulence onset did not change over time, whereas turbulence slope tended to increase in the ivabradine group (Table 6).

| Baseline | Δ 8 M–Ba | E, 95% CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDNN (ms) | Ivabradine | 102.6 ± 33.0 | 21.4 ± 39.9 | 19.1 (12.3–25.9) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 108.3 ± 35.5 | 0.3 ± 29.4 | |||

| SDANN (ms) | Ivabradine | 91.9 ± 31.4 | 19.9 ± 37.8 | 17.4 (11.0–23.9) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 97.3 ± 34.5 | 0.5 ± 28.6 | |||

| RMSSD (ms) | Ivabradine | 24.1 ± 12.4 | 5.0 ± 11.9 | 4.8 (2.5–7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 24.8 ± 10.3 | −0.1 ± 12.0 | |||

| NN50 (#) | Ivabradine | 5307 ± 6473 | 1483 ± 6240 | 1617 (491–2743) | 0.0050 |

| Placebo | 5711 ± 5973 | −342 ± 6622 | |||

| PNN50 (%) | Ivabradine | 5.8 ± 8.0 | 2.8 ± 7.6 | 3.0 (1.5–4.4) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 6.0 ± 6.6 | −0.2 ± 7.7 | |||

| TP (ms2) | Ivabradine | 11621 ± 7466b | 5627 ± 10402b | 5124 (3394–6853) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 12984 ± 8742b | 98 ± 6666 | |||

| ULF (ms2) | Ivabradine | 10722 ± 6939b | 5261 ± 9920 | 4781 (3135–6428) | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 12053 ± 8366b | 78 ± 6328 | |||

| VLF (ms2) | Ivabradine | 582 ± 521 | 203 ± 610 | 195 (92–299) | 0.0002 |

| Placebo | 618 ± 429 | −1 ± 405 | |||

| LF (ms2) | Ivabradine | 216.1 ± 291.8 | 113.3 ± 529.1 | 101.9 (12.8–191.1) | 0.0251 |

| Placebo | 217.1 ± 234.0 | 11.5 ± 318.6 | |||

| HF (ms2) | Ivabradine | 100.8 ± 143.6 | 49.1 ± 194.6 | 39.6 (4.6–74.6) | 0.0266 |

| Placebo | 96.2 ± 98.3 | 9.8 ± 143.5 | |||

| LF (n.u.) | Ivabradine | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.00 ± 0.02 | 0.00 (−0.00 to 0.01) | – |

| Placebo | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | |||

| HF (n.u.) | Ivabradine | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.00 (−0.00 to 0.00) | – |

| Placebo | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.02 | |||

| LF/HF | Ivabradine | 2.5 ± 1.6 | −0.3 ± 1.4 | −0.4 (−0.6– to −0.1) | – |

| Placebo | 2.7 ± 1.5 | −0.1 ± 1.2 | |||

| Baseline | 8 months | Δ 8 M–Ba | P-value | ||

| TO (%) | Ivabradine | −0.7 ± 1.4 | −0.8 ± 1.7 | −0.1 ± 1.6 | 0.22 |

| Placebo | −0.9 ± 2.1 | −0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.1 ± 2.0 | ||

| TS (ms/RR interval) | Ivabradine | 3.7 ± 3.9 | 4.1 ± 3.6 | 0.4 ± 3.7 | 0.31 |

| Placebo | 4.0 ± 5.1 | 3.9 ± 4.6 | −0.04 ± 4.7 |

- Values are presented as means ± standard deviations.

- For time or frequency domain parameters of heart rate variability, the estimate (E) of ivabradine minus placebo effect is shown, with differences between means based on a parametric covariance analysis adjusted for country.

- CI, confidence interval; HF, high frequency (0.15–0.4 Hz); LF, low frequency (0.04–0.15 Hz); NN50, number of interval differences of successive NN intervals >50 ms; n.u., normalized units; PNN50, percentage of interval differences of successive NN intervals >50 ms;RMSSD, root mean square of differences between successive normal-to-normal RR intervals; SDANN, standard deviation of average normal-to-normal RR intervals of 5 min segments of the 24-h recording; SDNN, standard deviation of all normal-to-normal RR intervals recorded over 24 h; TO, turbulence onset; TP, total power (variance of all NN intervals); TS, turbulence slope; ULF, ultra low frequency (<0.003 Hz); VLF, very low frequency (0.003–0.04 Hz).

- a Change from 8 months to baseline.

- b Root mean square of differences between successive normal-to-normal RR intervals.

Discussion

Ivabradine is a selective If current inhibitor that lowers HR by acting predominantly on the sinoatrial node.19, 20 This prospective substudy used a subset of the participants of the main SHIFT trial. It showed a beneficial effect of oral ivabradine in increasing HRV parameters and in tending to improve HRT parameters, whereas no significant changes of these parameters were observed in the placebo group. In addition, the HR-lowering effect of ivabradine was associated with a good safety profile. From baseline to 8 months, HR over 24 h was significantly reduced with ivabradine, but decreased minimally with placebo. This is consistent with the effects of ivabradine on HR found in other double-blind placebo-controlled studies.9, 10 Furthermore, in the main SHIFT study, as in the BEAUTIFUL study, a continuous direct association between baseline HR and ivabradine-associated benefits was noted.10, 21, 22

Heart rate in BEAUTIFUL and SHIFT was measured on ECG at rest in the office at baseline.9, 10, 18, 21, 22 Since office resting HR might vary according to the time of day and situation of recording, it is useful to know whether 24-h Holter-measured HR (awake, asleep, or over 24 h) responds similarly to office HR. Among these measures, night-time HR might be most predictive of risk,11 as well as lack of dipping on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.23 In contrast, ambulatory HR did not add prognostic information to that provided by office HR in elderly subjects with systolic hypertension,24 while in hypertensives generally, night-time HR is associated with mortality risk.25, 26 In a population with HF, this study uniquely assesses baseline HRs and the effect of ivabradine on office, 24-h average, asleep, and awake HRs, and reveals that HR reduction is quite similar and highly correlated. Baseline office HR is lower than 24-h Holter average and asleep HR, but similar to awake HR. This suggests that all these measures could be suitable for selection of patients eligible for ivabradine treatment for HF and to judge treatment effects on HR reduction by ivabradine.

The SHIFT study demonstrated that cardiovascular outcomes are improved with ivabradine in patients with moderate to severe systolic HF and high resting HRs.26 Ivabradine significantly reduced the incidence of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for worsening HF (primary composite endpoint) vs. placebo in patients already receiving guideline-based HF therapy. The relative risk reduction of 18% was substantial and statistically significant (P < 0.0001), and associated with reduced LV remodelling.27 The benefit of HR reduction with ivabradine was comparable and safe across all age groups of HF patients.28

Heart rate variability is affected by sympathetic and vagal modulation of the sinus node.8 HRV parameters are a measure of autonomic balance and have been used to evaluate the safety of pharmacological agents shown to be beneficial in HF13-15 and for risk stratification for sudden cardiac death.29 Both time and frequency domain measures of HRV are markedly attenuated in HF, which implies a higher rate of arrhythmia and of all events.8 The present study indicates that HRV parameters are improved by ivabradine, though they are unchanged by placebo. These results suggest that ivabradine on top of beta-blockers improves autonomic imbalance in HF. These results are consistent with those of the Holter substudy from the BEAUTIFUL trial, which included patients with stable CAD and LV dysfunction receiving ivabradine on top of beta-blockers in 93% of cases.30

SHIFT Holter confirms that HRV parameters can improve with ivabradine treatment in HF. In a recent study of 48 non-ischaemic patients with HF,31 ivabradine improved HRV after 8 weeks of treatment. Mean RR interval, SDNN, SDANN, and SDNN index all increased significantly (all P < 0.0001). Parameters of parasympathetic activity, pNN50 and RMSSD, also increased significantly after ivabradine administration (both P < 0.0001). This significant increase in time domain HRV indices occurred whether the patient was awake or asleep. Possible explanations for this improvement in HRV in HF with ivabradine include: prolonged diastole leading to improved cardiac blood supply and LV filling; beneficial effects on LV remodelling; and reduced sympathetic influence and enhanced vagal tone, leading to an improvement in sympathovagal balance. Pre-clinical studies have shown that ivabradine shifts sympathovagal balance towards vagal tone and decreases renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system stimulation by reducing AT1 receptor expression and angiotensin II levels.32, 33

Treatment with ivabradine also appears to improve HRV in ischaemic patients. A substudy of a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study in 319 patients with documented CAD and stable angina showed that 3 months' therapy with ivabradine significantly improved the main time domain parameters (SDNN, pNN50, and RMSSD) (all P < 0.001 vs. baseline).34 Possible mechanisms to explain the improvement in HRV with ivabradine therapy, particularly the parasympathetic component, include decreased myocardial oxygen demand and ischaemia; reduced sympathetic stimulation and adrenoreceptor-mediated cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and hypertrophy; and a diminished likelihood of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden death.34

This substudy found no evidence that ivabradine therapy is associated with potentially clinically important ventricular arrhythmias. Specifically, no sustained VT was observed, and non-sustained VT at 8 months was less frequent with ivabradine than with placebo. This clearly is reassuring in considering a drug indicated for patients with HF, who are at relatively high risk of sudden death and who have acquired abnormalities of cardiac sympathetic function. Indeed, in this regard, it is also reassuring that HRV and HRT are not adversely affected by ivabradine and that, in combination with beta-blockers, there is no tendency to arrhythmia. Conversely, supraventricular tachycardia, while infrequent in absolute terms, was relatively more frequent with ivabradine than with placebo, though no clinically important adversity was associated with this finding. Our study also adds to what is known about ivabradine and conduction disturbances in systolic HF.35 Ivabradine was recently shown to be safe and its treatment effect maintained in systolic HF patients with LBBB. Patients with this conduction abnormality are more prone to AF and asymptomatic bradycardia than those without LBBB.

The present study had some limitations. First, this substudy included only a small number of subjects (<10%) of the main SHIFT trial. However, there were no relevant differences in baseline characteristics between the two treatment arms, and the effects of ivabradine on office HR measured by ECG were also observed with Holter monitoring. Secondly, although no sample size calculation was performed, the number of HF patients on ivabradine in the substudy was considered sufficient to explore HRV and cardiac safety effectively with Holter monitoring in these patients. Thirdly, the effects of ivabradine on HRV could be related directly to HR reduction. Relatively high HR and relatively low HRV at baseline could be signs of autonomic dysfunction in HF. The mechanism of improved HRV by ivabradine is unknown, but the consistent improvement of time and frequency domain parameters suggests a direct effect of ivabradine rather than an effect solely of pharmacological HR reduction. Lastly, although suitable for the analysis of heart rate and HRV, the short duration of the study meant it was difficult to detect arrhythmic incidents, such as ventricular tachycardia, sinus pauses/arrest, and intermittent AF.

Conclusion

In summary, this prospective Holter substudy conducted in a subset of SHIFT patients showed a beneficial effect of ivabradine, with increased HRV parameters and improvement of the HRT parameters, and no evidence of proclivity for VT. The HR lowering by ivabradine was associated with a good safety profile and similar effects on resting, asleep, awake, and 24-h HR, making all these Holter parameters potentially suitable for identification of HF patients with HR ≥70 b.p.m., candidates for treatment with ivabradine.

Conflict of interest: M.B. reports receiving speaker's bureau fees from: Astra Zeneca, AWD Dresden, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Berlin-Chemie, Daiichi-Sankyo, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and Medtronic. J.B. performs research and receives honoraria for speaker's bureau from Servier and consulting fees and speaker's bureau from Amgen. J.C. is a consultant and advisor for Servier. I.F. has received research grants and honoraria for committee membership from Servier. M.K. is a member of the executive committee of SHIFT; and has received fees for speaker's bureau from Sanofi, Novartis, Servier, BMS, Astra Zeneca, and Menarini. L.T. has received research grants and honoraria from Servier. K.S. has received research grants and honoraria for lecturing from Servier. All other authors report no conflict of interest.