Sex hormones in heart failure revisited?

This article refers to ‘Impact of diabetes and sex in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients from the ASIAN-HF registry’ by C. Chandramouli et al., published in this issue on pages 297–307.

With the increasing longevity of ‘westernized’ populations, heart failure (HF) in the elderly has become a problem of growing scale and complexity. Affected individuals suffer impaired quality of life. Relatives as well as carriers suffer several years of distress and exhaustion. In addition, health services struggle to cope with the resource implications.

Loss of ovarian hormones accelerates aging in women including mortality from cardiovascular disease.1 In the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis),2 testosterone as well as oestradiol levels were measured in the 2834 post-menopausal women. During 12.1 years of follow-up, the higher testosterone/oestradiol ratio was significantly associated with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).2 Recently, special attention has been paid to HF in post-menopausal women.

In this issue of the Journal, the paper by Chandramouli et al.3 addresses this issue and provides new insight into the relationship between diabetes mellitus (DM) and sex in HFrEF patients from the ASIAN-HF registry. They found that Asian women with HFrEF were more likely to have DM and more concentric left ventricular geometry compared to men. Furthermore, DM confers worse quality of life and a greater risk of adverse outcomes in women than men.3 Among HF patients, DM is a common co-morbidity and confers worse prognosis.4, 5 Sex differences have been well-described in DM and HF separately. Women are often diagnosed with DM at a later age compared to men.6 Incident HF is two-fold higher in DM men and five-fold higher in DM women compared with their respective non-DM counterparts.7 Recent epidemiologic data have highlighted the large burdens of DM and HF, especially in Asia.8

Several important issues should be taken into account when interpreting the results from the ASIAN-HF registry.3 First, HF of ischaemic origin was highly included in the registry. If ischaemic HF was excluded, how would be the results? It would have been interesting to evaluate by sensitive analysis if ischaemic aetiology was a significant modifier of the relationship between DM and outcomes.3 If the relationships between DM and outcomes had been affected by ischaemic aetiology, it would have been likely that ischaemia, rather than diabetes, would have been the main variable affecting outcomes.

Second, the cause of mortality should be considered to understand the results from the ASIAN-HF registry.3 Because many HFrEF patients with ischaemic aetiology were included, the prevalence of death due to acute coronary syndrome might have been higher. If DM was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction/stroke death in HFrEF patients after adjusting for confounding variables,3 the relationship between DM and outcomes in HFrEF patients was suggested to be similar to that in high-risk patients at first-ever cardiovascular disease.

The ASIAN-HF registry demonstrated that women with HFrEF are more likely to have DM and more concentric left ventricular geometry compared to men. In addition, DM confers a greater risk of adverse outcomes in women than in men.3

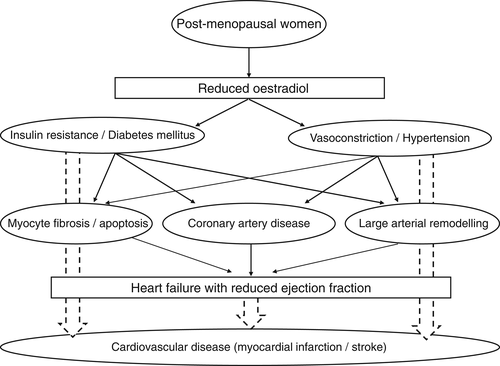

What were the mechanisms underlying the relationship among post-menopausal women, DM and their effects on HFrEF outcome? In MESA, Zhao et al.2 found that higher testosterone/oestradiol ratio and lower oestradiol levels were associated with increased risk of HFrEF, but not HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), the type of HF more commonly seen in older women. It is possible that reduced oestradiol during menopause affects vascular and cardiac remodelling processes that differentially lead to HFrEF vs. HFpEF phenotype. This mechanism might be true for the results in the ASIAN-HF registry.3

A previous study showed a role for oestradiol in regulating energy metabolism and opened new insights into the role of the two oestrogen receptors (ER), ERα and ERβ.9 Another review on the role of oestrogens and their receptors in the control of energy homeostasis and glucose metabolism in health and metabolic diseases showed that oestrogen actions in the hypothalamic nuclei differently control food intake, energy expenditure, and white adipose tissue distribution. Oestrogen actions in skeletal muscle, liver, adipose tissue, and immune cells are involved in insulin sensitivity as well as prevention of lipid accumulation and inflammation. Oestrogen actions in pancreatic islet β-cells also regulate insulin secretion, nutrient homeostasis, and survival. Oestrogen deficiency promotes metabolic dysfunction predisposing to obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and type 2 DM (T2DM).10

Findings on gene modulation by ERα and ERβ of insulin-sensitive tissues indicate that oestradiol participates in glucose homeostasis by modulating the expression of genes that are involved in insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake.9

A participation in the regulation of GLUT4 glucose transporters has been described.9 It has recently been reported that GLUT transporter expression is suppressed following high-fat diet feeding in mice, which could be a surrogate of metabolic syndrome and T2DM associated with enhanced vascular inflammation.11 However, triggering mechanisms of the inflammation in T2DM remain to be fully elucidated. Inflammatory responses likely contribute to T2DM occurrence through insulin resistance, and are in turn intensified in the presence of hyperglycaemia to accelerate long-term complications of DM. Pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to HF include neuroendocrine imbalance, metabolic alterations, and inflammation, leading to systemic alterations in HF. Targeting inflammatory pathways reading to dysregulation of glucose transport in T2DM could possibly be a component of the strategies to prevent and control DM and related complications, but an exact delineation of the relative role of the two ERs in inflammatory T2DM is still outstanding.

Blood vessels express ERs. Vascular smooth muscle cells and blood vessels from ERβ-deficient mice exhibit multiple functional abnormalities.12 In wild-type mice, oestrogen attenuates vasoconstriction by an ERβ-mediated increase in inducible nitric oxide synthase expression. In contrast, oestrogen augments vasoconstriction in blood vessels from ERβ-deficient mice. Furthermore, ERβ-deficient mice develop sustained systolic and diastolic hypertension as they age.12 These data support an essential role for ERβ in the regulation of vascular function and blood pressure.

Although the heart responds to oestrogen, it has been unclear whether oestrogen acts directly on heart muscle or indirectly by means of the vascular, immune, or nervous system. In ERβ-deficient mice, histological and ultrastructural analysis of the heart revealed a disarray of myocytes, a disruption of intercalated discs, an increase in the number and size of gap junctions, and a profound alteration in nuclear structure.9 Immunohistochemical studies with ERβ antibodies failed to detect ERβ in the myocardium, concluding that abnormalities in heart morphology in ERβ-deficient mice are likely due to stress on the nuclear envelope as a result of sustained systolic and diastolic hypertension.13 Because neither ERα nor ERβ could be detected in heart muscle, the effects of oestrogen on the myocardium seem to be indirect.13

Moreover, one has to take into account the fact that different polymorphisms have been described in steroid hormone receptors that are related to variable human diseases. Polymorphisms of ERα and ERβ are related not only to reproductive diseases, but also to osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, malignancy such as breast cancer, and central nervous system disorders. They are also related to individual reactivity to medications. Polymorphisms leading to an increased risk of HF as a co-morbidity of DM should be investigated more deeply in the future.

Taken together, from these stand points of views, reduced oestradiol in post-menopausal women is suggested to be associated with disrupted glucose homeostasis and increased blood vessel tonus, and indirectly moderate their effects on reduced left ventricular contraction via afterload mismatch (Figure 1). In fact, women with DM had higher baseline systolic blood pressure than other groups.3 In addition, HFrEF most commonly develops in response to distinct pathophysiologic perturbations leading to accelerated and larger-scale myocyte loss with the most common aetiology of ischaemic heart disease that was found in the results in the ASIAN-HF registry.3

In the early 1990s, reversible cardiomyopathy precipitated by acute emotional stress was reported.14 The patients were usually post-menopausal women and often developed signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome proximate to a strong emotional stressor associated with a transient apical and mid-ventricular wall motion abnormality despite the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease at the time of emergent coronary angiography.14, 15 This syndrome was originally termed as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.15 Although the clinical manifestations of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and those in HFrEF with DM are different, the status of post-menopausal women seems to be a common risk, and reduced oestradiol level might serve as a common underlying pathophysiology. The complexity for the relationship between sex steroid hormone and cardiovascular system gives us a glimpse to understand the precise pathophysiology in those disorders.

Until now, there have been few reports assessing the relationships among post-menopausal women, DM and HFrEF outcomes using a prospective study design. Thus, the data presented in the manuscript by Chandramouli et al.3 provide further insight into sex-specific approaches in HF. Sex hormones in HF might revisit.

Conflict of interest: none declared.