Too young for an acquired cardiomyopathy? Cobalt metallosis as a cardiac amyloidosis mimicker

Abstract

Metallosis with subsequent cardiac involvement is a possible long-term complication of hip arthroplasty. We report the case of a young female referred to our centre for the suspicion of cardiac amyloidosis presenting with low electrocardiogram voltage, left ventricular hypertrophy, pericardial effusion, and global and longitudinal systolic impairment with apical sparing pattern. Her medical history was remarkable for arthroplasty in the context of congenital hip dysplasia. Two years prior to presentation, she underwent revision surgery for prosthesis malfunction, and tissue metallosis was initially documented. At the current presentation, cobalt metallosis was confirmed, as the circulating cobalt and chromium levels were severely elevated. The accurate diagnosis prompted the removal of the cobalt source with extensive tissue debridement and the use of chelating agents. Reversal of the cardiac abnormalities occurred as the circulating cobalt levels returned to normal.

Introduction

Cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy is a distinct cause of heart failure seen in patients with previous metal-on-metal joint replacement. The cardiac abnormalities are heterogeneous and not entirely specific, including various degrees of ventricular systolic dysfunction, ventricular hypertrophy and/or dilatation, pericardial effusion, and tachycardia, which are usually reversible if the cobalt source (e.g. prosthesis) is timely removed.1 Extreme presentations have been described, including electrical storm or cardiogenic shock requiring ventricular assist devices and heart transplantation.2-4 Due to the fact that it can imitate other acquired or hereditary cardiomyopathies, correct diagnosis and specific management are often delayed.5

Case report

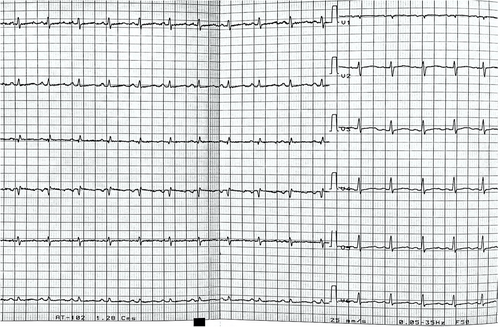

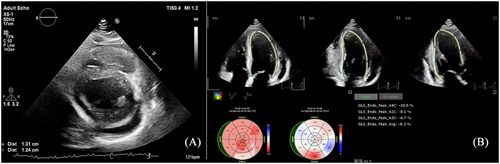

A 25-year-old female with a history of dyspnoea on light exertion and palpitations for the past 3 months was referred to our centre for further evaluation with the suspicion of cardiac amyloidosis. Her medical history included a total hip arthroplasty in 2014 for congenital hip dysplasia. In the last couple of years, she has also been investigated for autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, upper limb rash, hypothyroidism, amenorrhoea, and progressive hearing impairment. Family history was unremarkable. Cardiac biomarkers were abnormal, with an N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level of 549 pg/mL (upper level of normal 125 pg/mL) and high-sensitivity troponin of 80 ng/L (upper level of normal 26 ng/L). Mild lactic acidosis was also noted (pH 7.33, lactate level 4.7 mmol/L). The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia, left atrial enlargement, low voltage, and QS complex in V1 (Figure 1). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed predominantly septal hypertrophy (13 mm), mildly impaired left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF; 44%), and a severely impaired longitudinal function with apical sparing pattern [global longitudinal strain (GLS) −8.3%] (Figure 2). The right ventricle (RV) had an impaired longitudinal function (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion 15 mm). Diastolic function could not be determined due to tachycardia. Mild to moderate pericardial effusion was noted, without any signs of constriction. The findings of low ECG voltage and LV increased wall thickness, impaired longitudinal function with apical sparing pattern, and pericardial effusion are suggestive of cardiac amyloidosis. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was ordered. T1 mapping showed a slightly elevated global value of 1153 ms, higher in the septal region (1183 ms), while in T2, the same area showed hypersignal (ratio 2.8) and elevated value of 53 ms. T2* was normal, excluding iron overload. Extracellular volume was increased (30%), particularly in the basal lateral wall (35%) (Figure 3). Notably, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was observed only in this area. The pericardium appeared diffusely thickened, with a maximum thickness of 6 mm, without any LGE. The pericardial effusion was suggestive of a serosanguineous fluid (hypointense signal in T2 HAST and hyperintense in T1 Dixon). The CMR findings were consistent with an infiltrative cardiomyopathy.

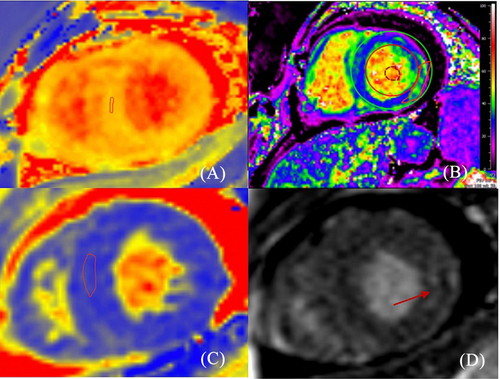

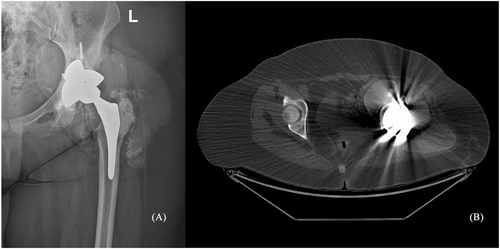

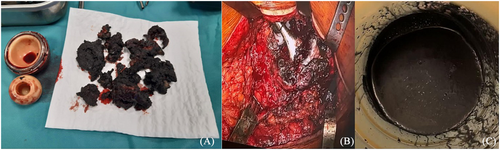

The first hip prosthesis implanted in 2014 had undergone revision in 2020 for malfunction, 2 years prior to the present referral. The revision surgery had revealed extensive tissue metallosis secondary to abnormal metal-on-metal contact, caused by the fracture of the acetabular component (Figure 4). No cardiological workup is available from that moment. Due to the high suspicion of metallosis, the cobalt and chromium blood levels were tested, revealing elevated values: 1550 μg/L (normal < 1 μg/L) for cobalt and 125 μg/L (normal < 2.1 μg/L) for chromium. The findings were indicative of cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy. She was started on heart failure treatment with loop diuretic and beta-blocker. Chelation treatment with glutathione, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and acetylcysteine was also indicated by the toxicologist. The patient was evaluated 3 months after, and despite a reduction of the cobalt circulating levels (1000 μg/L), the global and longitudinal systolic function worsened (LVEF 36% and GLS −4%). The orthopaedic surgeon was consulted, and prosthetic failure complicated with soft tissue metallosis was confirmed with imaging (Figure 5). For the second revision surgery, the ACS NSQIP risk score for serious complications was 4%, higher than average, but not prohibitive. Thus, the patient underwent revision, which involved removal of the prosthesis, extensive tissue debridement, and total hip arthroplasty. One month after the surgery, the cobalt levels dropped to 481 μg/L, with a further drop to 17 μg/L at 6 months. In parallel, the cardiac impairment significantly improved with resolution of sinus tachycardia, normal LV wall thickness, and improvement of LVEF (50%), GLS (−11.4%), and NT-proBNP levels (184 pg/mL), thus confirming the hypothesis of metal toxicity (Figure 5).

Discussion

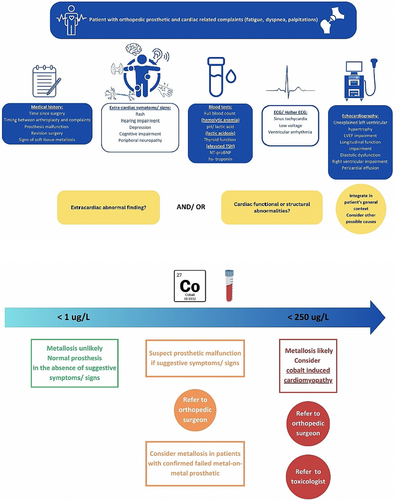

Elevated cobalt circulating levels can occur in patients with hip arthroplasty in whom metal debris enters the bloodstream and is deposited in distant tissues (e.g. heart) with subsequent metallosis. Cobalt levels are generally low in the majority of implanted patients but may become increased in patients with excessive wear, particularly those requiring surgical revision.6, 7 Metallosis is a rare complication in hip arthroplasty, and it is more commonly related to metal-on-metal bearings. The occurrence of extensive metallosis is exceedingly rare and poses a significant challenge for orthopaedic diagnosis, as patients may remain asymptomatic until a catastrophic failure occurs.8 One of the key challenges was that our patient had no symptoms and had a good range of motion in the left hip. Signs of metallosis appeared before any symptoms related to the hip prosthesis. Cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy comprises a spectrum of cardiac abnormalities in patients with elevated cobalt circulating levels, with different thresholds being suggested in the literature: >250 or >300 μg/L.9 Importantly, diagnosis is supported by the normalization of cardiac structure and function after exposure ceases and cobalt concentrations decline.1

The cardiac phenotype is variable, featuring electrical abnormalities (low ECG voltage and sinus tachycardia) and structural abnormalities, such as increased ventricular wall thickness, systolic impairment of the LV and/or RV, dilated cavities, diastolic dysfunction, including a restrictive pattern, and pericardial effusion.1 Magnetic resonance imaging hyperenhancement with non-specific patterns, abnormal T2 due to myocardial oedema, and mildly elevated T1 and extracellular volume values are reported in cases of cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy.10, 11 Thus, it can mimic other cardiomyopathies, such as dilated or infiltrative cardiomyopathies. The differential diagnosis with cardiac amyloidosis, initially sought in our patient as well based on several red flags, can be particularly challenging, as illustrated by the present case and previous reports.5 Pivotal in guiding diagnosis was the clinical context of the patient with the history of the prosthetic device followed by revision surgery, as well as the extracardiac manifestations attributable to cobalt toxicity: diffuse rash, lactic acidosis, hearing impairment, destructive thyroiditis with hypothyroidism, and haemolytic anaemia (Figure 6). Ultimately, based on the clinical suspicion and awareness of this association, we were able to confirm the diagnosis given the elevated baseline cobalt circulating levels and the improvement of cardiac function after the cobalt source was removed and cobalt levels fell dramatically.

Management of cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy includes heart failure treatment according to current guidelines. However, the impact of standard heart failure therapies on prognosis is limited, and long-term prognosis depends on the normalization of circulating cobalt levels and termination of exposure to cobalt, which is achievable by removing the cobalt source and, to a lesser extent, with chelation agents.4 Of note, as seen in our case, improvement of cardiac function occurred only after removal of the cobalt source, even if the circulating cobalt levels declined modestly with chelation agents. If exposure persists, the course of cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy is progressive, towards severe systolic dysfunction and death. Extreme presentations, such as cardiogenic shock or electric storm, requiring advanced mechanical circulatory support and heart transplantation can occur in patients who either were not previously diagnosed or failed to show reversal of cardiac abnormalities.2-4, 12

Conclusions

Awareness regarding the existence of cobalt cardiomyopathy is crucial in patients with hip prosthesis, as they can mimic other cardiomyopathies, but their prognosis and chances of cardiac function recovery are dependent on the removal of the cobalt source.

Conflict of interest

None declared.