Angiographic classification of total occlusion and its implication on balloon pulmonary angioplasty

Tao Yang and Xin Li contributed equally to this work and shared first authorship.

Abstract

Aims

Despite refinements in balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA), total occlusion remains a challenge in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). Owing to their low success and high complication rates, most interventional cardiologists are reluctant to address total occlusion, and there is a paucity of literature on BPA performance in total occlusion. We aimed to classify total occlusion according to morphology and present an illustrative approach for devising a tailored treatment strategy for each distinct type of total occlusion.

Methods and results

All patients diagnosed with CTEPH who underwent BPA between May 2018 and May 2022 at Fuwai Hospital in Beijing, China, were included retrospectively. A total of 204 patients with CTEPH who underwent BPA were included in this study. Among these, 38 occluded lesions were addressed in 33 patients. Based on the morphology, we categorized the lesions into three groups: pointed-head, round-head, and orifice occlusions. Pointed-head occlusion could be successfully addressed using soft-tip wire, round-head occlusion warranted hard-tip wire and stronger backup, and orifice occlusion warranted the strongest backup force. The success rates for each group were as follows: pointed-head (95.45%), round-head (46.15%), and orifice occlusion (33.33%), with orifice occlusion having the highest complication rate (50%). The classification of occlusion was associated with BPA success (round-head occlusion vs. pointed-head occlusion, OR 24.500, 95% CI 2.498–240.318, P = 0.006; orifice occlusion vs. pointed-head occlusion, OR 42.000, 95% CI 3.034–581.434, P = 0.005).

Conclusions

Occlusion morphology has a significant impact on BPA success and complication rates. A treatment strategy tailored to each specific occlusive lesion, as outlined in the present study, has the potential to serve as a valuable guide for clinical practitioners.

Introduction

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is characterized by the persistent obstruction of the proximal pulmonary arteries by fibrothrombi and peripheral microvascular disease, which can lead to right-sided heart failure and mortality.1 Pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) enables complete removal of visible obstructive elements within the pulmonary arteries and is recommended for operable patients. Nevertheless, a notable proportion, >40% of patients, are precluded from undergoing PEA because of factors such as surgically inaccessible lesions, compromised general health status, or concurrent comorbidities. For inoperable patients or those with persistent PH after PEA, the 2022 European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society guidelines recommend balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA).2

To facilitate BPA performance, Kawakami et al. introduced an angiographic classification of pulmonary artery lesions in 2016. This classification categorizes lesions into five distinct types: ring-like stenosis, web lesions, subtotal lesions, totally occluded lesions, and tortuous lesions.3 Subsequently, this framework gained broad acceptance within the medical community. Despite the considerable achievements observed with BPA in pulmonary artery revascularization, total occlusion remains a challenge and many interventionists are reluctant to address occlusive lesions.4 Among all the treated lesions, attempts on total occlusion account for less than 5%.5 Within the limited experience in addressing total occlusion, the reported success rate is as low as 52.2% and is accompanied by a high complication rate. Conversely, compared with other types of lesions, addressing occlusive lesions yields the greatest haemodynamic benefit.6 Therefore, the treatment of total occlusion presents a dilemma for clinicians, warranting guidance on treatment strategy.

In this study, we aimed to further classify total occlusion according to morphology on pulmonary angiography. Furthermore, we aimed to illustrate the device and strategy used, as well as to assess the efficacy and safety in treating different types of total occlusions, which may guide clinicians in performing BPA for total occlusions.

Methods

Study design and patient enrollment

All patients diagnosed with CTEPH who underwent BPA between May 2018 and May 2022 at Fuwai Hospital in Beijing, China, were included. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and approved by the institutional Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Clinical parameters were collected from digital medical records by two reviewers independently, including demographics, World Health Organization functional class (WHO FC), 6-min walk distance (6MWD), parameters derived from laboratory examinations, right heart catheterization (RHC), and echocardiography. The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated according to the Chinese-modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.7

Right heart catheterization and balloon pulmonary angioplasty

The RHC and BPA were conducted in line with previous description.8 RHC was conducted via the femoral or jugular vein subsequent to the administration of local anaesthesia using a 7-F catheter. Baseline haemodynamics were assessed, encompassing measurements of right atrial and ventricular pressure; pulmonary arterial pressure; cardiac output (computed following the indirect Fick's method); and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP). Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was calculated using the following formula: (mPAP – PAWP)/cardiac output.9 When performing BPA, a 6 Fr guiding catheter (Multi-purpose [Cordis Corporation, Bridgewater, NJ, USA], Amplatz Left [Terumo® Heartrail™ II; Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan], or Judkins Right [Terumo® Heartrail™ II; Terumo Corporation] or IL-3.5) was introduced to pulmonary arteries through a 7 Fr long sheath (Flexor® Check-Flo® Introducer; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA). When a stronger backup was warranted, a guide extension catheter was applied (5 Fr system in a 6 Fr system or Guidezilla catheter). After introducing the guiding catheter into the targeted pulmonary arteries, selective pulmonary angiography was performed to obtain a precise view of the targeted arteries. Based on the selective pulmonary angiography, a 0.014-inch guidewire (Fielder XT-R or Sion) advanced to the target lesion. In lesions with extremely hard intimal layers, a hard-tip wire (Conquest Pro or Gaia Third), microcatheter, or parallel wire was used to increase the backup force and change the wire. When the wire and balloon catheter successfully passed the lesion, a 1.25 or 2.0 mm diameter balloon was initially selected for dilation according to the lumen of the lesion. Subsequently, a 2.0 mm or larger balloon was applied for repeated dilation. Haemodynamics were re-evaluated 3 months after BPA treatment. All procedures were performed under the guidance of an experienced interventional cardiologist, Zhihui Zhao.

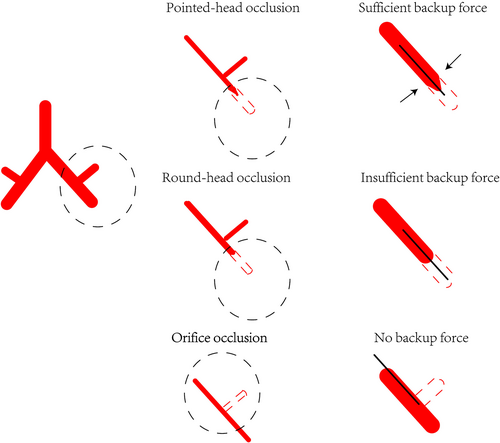

Classification of total occlusion

Total occlusion was classified into three groups based on angiographic morphology: type A, pointed-head occlusion; type B, round-head occlusion; and type C, orifice occlusion. Pointed-head occlusion was defined as the diameter of occlusive cap ≤5 mm, round-head occlusion was defined as the diameter of the occlusive cap >5 mm, and orifice occlusion was defined as total obstruction of the pulmonary lobe or its constituent segments.

Selecting methods for treating occlusive lesions

Total occlusion lesions were accompanied with low success rate and high complication rate.3, 10 Therefore, not all of the total occlusion lesions were addressed. For patients whose haemodynamics have not yet recovered to a relatively ideal degree, and the mPAP and PVR were relatively high, total occlusions were not addressed given the high risk of complications.

Success of balloon pulmonary angioplasty

Successful BPA was defined as revascularization of the targeted vessels, that is, the wire successfully traversed the designated lesion, subsequently facilitating its dilation using the balloon.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the variables was examined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Independent-sample t-tests were applied to assess continuous parameters with a normal distribution and presented the results as mean ± standard deviation. Conversely, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for continuous parameters with abnormal distributions, and the data were presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical parameters were presented as counts (percentages). Paired-sample t tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied to evaluate the differences between baseline and follow-up. The chi-squared test was employed to evaluate disparities in categorical parameters between the groups. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify parameters that correlated with BPA success. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Clinical features of total cohort at baseline

In this study, 204 CTEPH patients underwent 602 BPA sessions between May 2018 and May 2022. The mean age was 59.54 ± 10.79 years and 110 (53.9%) were female. The median disease duration was 3 (1, 7) years. At baseline, patients had impaired cardiac function (N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP] 781.00 [203.23, 1735.25] ng/L), reduced exercise capacity (6 MWD 353.17 ± 111.03 m), and poor haemodynamics (mPAP 48.97 ± 12.13 mmHg) (Table 1). Despite comparable baseline demographics, patients with total occlusion exhibited notably poorer haemodynamics compared with those without total occlusion, as evidenced by higher mPAP (50.51 ± 11.89 mmHg vs. 47.16 ± 12.23 mmHg, P = 0.049) and PVR (10.07 ± 4.72 wood units vs. 8.71 ± 4.33 wood units, P = 0.029) (Table 1).

| Variables | Total (n = 204) | Without total occlusion (n = 94) | With total occlusion (n = 110) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.54 ± 10.79 | 58.73 ± 10.64 | 60.24 ± 10.92 | 0.204 |

| Female, n (%) | 110 (53.9) | 51 (54.3) | 59 (53.6) | 0.827 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.96 ± 3.31 | 24.17 ± 3.48 | 23.77 ± 3.17 | 0.399 |

| WHO FC | 0.160 | |||

| I or II, n (%) | 70 (34.31) | 37 (39.4) | 33 (30.0) | |

| III or IV, n (%) | 134 (65.69) | 57 (60.6) | 77 (70.0) | |

| Disease duration, years | 3 (1, 7) | 3 (1, 6) | 4 (1, 8) | 0.114 |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 781.00 (203.23, 1735.25) | 660.75 (184.00, 1,624) | 839.10 (223.25, 1887.5) | 0.223 |

| 6MWD, m | 353.17 ± 111.03 | 360.52 ± 107.09 | 346.87 ± 114.43 | 0.718 |

| Targeted therapy according to pathway | ||||

| PDE5i, n (%) | 43 (21.1) | 23 (24.5) | 20 (18.2) | 0.273 |

| ERA, n (%) | 23 (11.3) | 15 (16.0) | 8 (7.3) | 0.051 |

| Prostacyclin analogues, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | 0.911 |

| Riociguat, n (%) | 94 (46.1) | 42 (44.7) | 52 (47.3) | 0.711 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| RVED, mm | 33.70 ± 7.31 | 33.71 ± 6.89 | 33.69 ± 7.69 | 0.708 |

| LVED, mm | 41.19 ± 5.65 | 41.80 ± 5.42 | 40.67 ± 5.81 | 0.156 |

| RVED/LVED | 0.84 ± 0.25 | 0.83 ± 0.23 | 0.86 ± 0.27 | 0.645 |

| TRV, m/s | 4.29 ± 0.71 | 4.27 ± 0.68 | 4.31 ± 0.73 | 0.571 |

| LVEF, % | 65.66 ± 6.40 | 66.11 ± 5.80 | 65.28 ± 6.87 | 0.488 |

| TAPSE, mm | 17.17 ± 4.11 | 17.41 ± 4.15 | 16.97 ± 4.09 | 0.354 |

| Haemodynamics | ||||

| SvO2, % | 66.38 ± 8.30 | 66.02 ± 10.01 | 66.69 ± 6.54 | 0.902 |

| mRAP, mmHg | 7.94 ± 3.74 | 7.88 ± 3.67 | 7.98 ± 3.81 | 0.862 |

| mPAP, mmHg | 48.97 ± 12.13 | 47.16 ± 12.23 | 50.51 ± 11.89 | 0.049 |

| PAWP, mmHg | 10.33 ± 2.36 | 10.29 ± 2.63 | 10.36 ± 2.11 | 0.829 |

| CO, L/min | 4.94 ± 1.33 | 5.07 ± 1.24 | 4.83 ± 1.39 | 0.239 |

| Cardiac index, L/(min.m2) | 2.71 ± 0.64 | 2.79 ± 0.65 | 2.64 ± 0.63 | 0.101 |

| PVR, wood units | 9.45 ± 4.58 | 8.71 ± 4.33 | 10.07 ± 4.72 | 0.029 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| ALT, IU/L | 23.10 ± 13.88 | 22.66 ± 12.91 | 23.45 ± 14.67 | 0.697 |

| AST, IU/L | 29.43 ± 10.15 | 29.47 ± 10.03 | 29.39 ± 10.30 | 0.959 |

| TBil, μmol/L | 18.42 ± 11.22 | 18.04 ± 10.39 | 18.74 ± 11.90 | 0.671 |

| CREA, μmol/L | 85.16 ± 16.51 | 83.70 ± 14.26 | 86.35 ± 18.13 | 0.274 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 93.60 ± 19.09 | 94.84 ± 16.82 | 92.59 ± 20.78 | 0.421 |

- Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or number (percentage). Baseline refers to the clinical features prior to the first BPA session.

- ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CREA, creatinine; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; mRAP, mean right atrial pressure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PAWP, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RVED/LVED, right ventricular end-diastolic diameter/left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; 6MWD, 6-min walk distance; SVO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation; TBil, total bilirubin; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity; WHO FC, World Health Organization functional class.

Clinical features of patients prior to addressing total occlusion

Among all the patients, 33 underwent BPA for total occlusion lesions. The total occlusion lesions in other 77 patients were not addressed owing to high mPAP and PVR. Fifteen (45.45%) patients underwent BPA because of distal lesions, seven (21.21%) refused PEA, five (15.15%) because of comorbidities or high risk, five (15.15%) owing to advanced age, and one (3.03%) had residual PH after PEA. Total occlusion was commonly addressed during the third BPA session. Prior to treatment of total occlusion, patients were in a relatively stable state with low NT-proBNP levels (234.2 [82.95, 719.4] ng/L), optimal exercise capacity (6 MWD 429.13 ± 84.69 m), and relatively low mPAP (40.36 ± 12.37 mmHg) (Table 2).

| Variables | N = 33 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.94 ± 14.45 |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (39.39) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.69 ± 3.69 |

| Reason for BPA | |

| Advanced age | 5 (15.15) |

| Post PEA | 1 (3.03) |

| Comorbidities/high risk | 5 (15.15) |

| Refusal PEA | 7 (21.21) |

| Distal lesions | 15 (45.45) |

| WHO FC | |

| I or II, n (%) | 18 (54.55) |

| III or IV, n (%) | 15 (45.45) |

| Disease duration, years | 3 (1, 8) |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 234.2 (82.95, 719.4) |

| 6MWD, m | 429.13 ± 84.69 |

| Targeted therapy at baseline | |

| PDE5i, n (%) | 2 (6.06) |

| ERA, n (%) | 3 (9.09) |

| Prostacyclin analogues, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Riociguat, n (%) | 15 (45.45) |

| Echocardiography | |

| RVED, mm | 30.65 ± 5.51 |

| LVED, mm | 44.26 ± 5.89 |

| RVED/LVED | 0.72 ± 0.21 |

| TRV, m/s | 3.78 ± 1.10 |

| LVEF, % | 64.88 ± 4.54 |

| TAPSE, mm | 19.42 ± 3.80 |

| Haemodynamics | |

| SvO2, % | 67.53 ± 6.97 |

| mRAP, mmHg | 8.12 ± 4.66 |

| mPAP, mmHg | 40.36 ± 12.37 |

| PAWP, mmHg | 10.91 ± 3.39 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 5.20 ± 1.43 |

| Cardiac index, L/(min.m2) | 3.00 ± 0.72 |

| PVR, wood units | 6.70 ± 4.17 |

| Laboratory tests | |

| ALT, IU/L | 18.48 ± 9.63 |

| AST, IU/L | 26.88 ± 7.70 |

| TBil, μmol/L | 16.41 ± 8.56 |

| CREA, μmol/L | 88.89 ± 15.62 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 92.48 ± 16.98 |

- Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or number (percentage). Parameters presented were the clinical features prior to the BPA session addressing total occlusion.

- ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CREA, creatinine; BPA, balloon pulmonary angioplasty; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, Estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; mRAP, mean right atrial pressure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PAWP, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PEA, pulmonary endarterectomy; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RVED/LVED, right ventricular end-diastolic diameter/left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; 6MWD, 6-min walk distance; SVO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation; TBil, total bilirubin; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity; WHO FC, World Health Organization functional class.

Classification of total occlusion lesions according to pulmonary angiography

In the total cohort, 38 occlusion lesions were addressed in 33 patients over 41 BPA attempts. Among the 38 total occlusion lesions, 31 (81.58%) were located at the segmental level, six (15.79%) at the lobar level, and one (2.63%) at the trunk level. Based on morphology, we further classified the total occlusions into three groups: type A, pointed-head occlusion; type B, round-head occlusion; and type C, orifice occlusion (Table 3, Figures 1 and 2).

| Variables | Total (38 lesions with 41 BPA attempts) | Pointed-head occlusion (22 lesions with 22 BPA attempts) | Round-head occlusion (10 lesions with 13 BPA attempts) | Orifice occlusion (6 lesions with 6 BPA attempts) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||

| Trunk, n (%) | 1 (2.63) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.67) |

| Lobar branches, n (%) | 6 (15.79) | 2 (9.09) | 2 (20) | 2 (33.33) |

| Upper/middle, n (%) | 1 (2.63) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Lower, n (%) | 5 (13.16) | 2 (9.09) | 1 (10) | 2 (33.33) |

| Segment, n (%) | 31 (81.58) | 20 (90.91) | 8 (80) | 3 (50) |

| Upper/middle, n (%) | 16 (42.11) | 9 (40.91) | 7 (70) | 0 (0) |

| Lower, n (%) | 15 (39.47) | 11 (50.0) | 1 (10) | 3 (50) |

| Guide catheter per attempt | ||||

| JR4, n (%) | 37 (90.24) | 22 (100) | 10 (76.92) | 5 (83.33) |

| AL1, n (%) | 2 (4.88) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.38) | 0 (0) |

| IL-3.5, n (%) | 2 (4.88) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.69) | 1 (16.67) |

| Guide-extension catheter per attempt | ||||

| 5 Fr in 6 Fr, n (%) | 3 (7.32) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.38) | 1 (16.67) |

| Guidezilla, n (%) | 4 (9.76) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.38) | 2 (33.33) |

| Guidewire per attempt | ||||

| Fielder XT-R, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 1 (4.55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sion, n (%) | 40 (97.56) | 21 (95.45) | 13 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Hard-tip wire per attempt | ||||

| Conquest Pro, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.69) | 0 (0) |

| Gaia Third, n (%) | 14 (34.15) | 0 (0) | 8 (61.54) | 6 (100) |

| Special technique per attempt | ||||

| Usage of microcatheter, n (%) | 2 (4.88) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.38) | 0 (0) |

| Parallel wire, n (%) | 3 (7.32) | 1 (4.55) | 1 (7.69) | 1 (16.67) |

| Diameter of the smallest balloon, mm | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (2, 2) |

| Diameter of the largest balloon, mm* | 2 (2, 3) | 2 (2, 3) | 2.5 (2, 3.75) | 4 (4, 4) |

| Success rate per attempt, n (%) | 29 (70.73) | 21 (95.45) | 6 (46.15) | 2 (33.33) |

| Complication per attempt, n (%) | 3 (7.32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) |

| Patency of successfully addressed vessels at follow-up, n (%) | 28 (96.55) | 21 (100) | 6 (100) | 1 (50) |

- AL1, Amplatz left; JR4, 4-Fr Judkins Right-4 diagnostic catheter. Complication refers to dissection; other types of complications were not observed when addressing total occlusion. Gram load of each guidewire is Fielder XT-R (0.6 g), Sion (0.8 g), Conquest Pro (9 g) and Gaia third (4.5 g).

- * Diameter of the largest balloon means the largest size of balloon applied in the BPA session for the total occlusion, and in the following BPA sessions, the size of balloon would further increase.

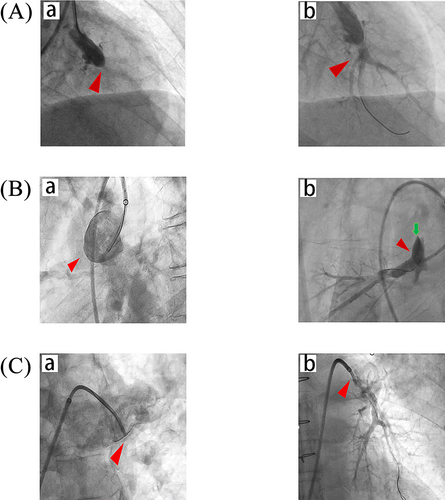

Type A, pointed-head occlusion was characterized by a pointed occlusive cap (diameter of occlusive cap ≤5 mm) with no trace of vessels distal to the lesion. Of the 22 treated pointed-head occlusions, 20 (90.91%) were located in the segmental pulmonary arteries and two (9.09%) in the lobar branches. The lesions were initially dissected using a Judkins Right guiding catheter without the assistance of a guide extension catheter. Subsequently, a Sion guidewire was applied to penetrate the hard layers of 21 lesions and one lesion was revascularized using the Fielder XT-R guidewire. No hard-tip wire was used for penetration, and one lesion was addressed using the parallel wire technique. For initial dilation, a 2.00 mm balloon was applied and, for sequential dilation, a 3.0 mm balloon was applied. BPA was successful in 21 of 22 attempts without complications. The 21 successfully revascularized lesions remained patent at follow-up after 3 months.

In type B, round-head occlusion was characterized by a wide occlusive cap (diameter of the occlusive cap >5 mm), leaving a pocket-like opacity proximal to the occluded arteries without blood flow to the distal vessels. The Judkins Right guiding catheter was primarily used to dissect the intimal lesions (76.92%). Four lesions were assisted using a guide extension catheter, including a 5 Fr system in a 6 Fr system (two lesions) and a Guidezilla catheter (two lesions). Subsequently, a Sion guidewire was applied to penetrate the occlusive cap, and nine lesions were further assisted using a hard-tip wire. The microcatheter was applied to two lesions (15.38%), and one lesion (7.69%) was addressed using the parallel wire technique. A 2.0 mm balloon was applied for the initial dilation, which progressively increased to a 3.0 mm or 4.0 mm balloon. Compared with pointed-head occlusion, the success rate was significantly lower for round-head occlusion. BPA was successful in six attempts (46.15%) without complications, and one lesion was successfully revascularized at the third attempt. All revascularized lesions remained patent at follow-up.

In type C, orifice occlusion was predominantly situated at the beginning of the arteries and was characterized by total obstruction of the pulmonary lobe or its constituent segments with no signs of the origin. Considering the imperceptibility of both the origin and configuration of the occluded arteries, addressing orifice occlusion is extremely difficult. The location of the orifice occlusion was more proximal than that for other types of lesions. Among the six lesions that were addressed, one (16.67%) was located at the trunk, two (33.33%) at the lobar branches, and three (50%) at the segmental arteries. In addition to the guiding catheter, half of the lesions were assisted via a guide extension catheter for initial dissection, including a 5 Fr system in a 6 Fr system (one of six lesions, 16.67%) and a Guidezilla catheter (two of six lesions, 33.33%). Subsequently, a Sion guidewire was applied for penetration, assisted by a Gaia Third hard-tip wire. The parallel wire technique was applied in one case (16.67%). A 2.0 mm balloon was initially applied for dilation, which progressively increased to 3.0 or 4.0 mm balloon. Compared with other types of total occlusion lesions, the success rate was the lowest in orifice occlusion (33.33%) and the complication rate was the highest (50%). Dissection was the most common complication. Of the two successfully revascularized lesions, one lesion, which was located on the left pulmonary artery trunk, restenosed 6 months after BPA, whereas the other lesion, which was located in the segmental pulmonary artery, remained patent at follow-up after 3 months.

Improvement after revascularization of total occlusion

BPA was successful in 25 of the 33 patients. After a median follow-up of 3 months, cardiac function improved significantly after revascularization of total occlusion, which was reflected by better WHO FC (WHO FC I or II, pre vs. post: 48% vs. 72%, P = 0.021), more favourable echocardiographic results (right ventricular end-diastolic diameter/left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, pre vs. post: 0.71 ± 0.21 vs. 0.63 ± 0.14, P = 0.002), significantly decreased mPAP (pre vs. post: 41.20 ± 11.00 mmHg vs. 35.96 ± 10.48 mmHg, P = 0.002), and reduced level of NT-proBNP (pre vs. post: 234.2 [107.05, 801.4] ng/L vs. 141 [82.3, 334.5] ng/L, P = 0.021] (Table 4).

| Variables | Before (n = 25) | After (n = 25) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO FC | 0.021 | ||

| I or II, n (%) | 12 (48) | 18 (72) | |

| III or IV, n (%) | 13 (52) | 7 (28) | |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 234.2 (107.05, 801.4) | 141 (82.3, 334.5) | 0.021 |

| 6MWD, m | 409.21 ± 102.83 | 452.21 ± 108.33 | 0.009 |

| Echocardiography | |||

| RVED, mm | 30.36 ± 5.07 | 28.48 ± 4.87 | 0.026 |

| LVED, mm | 44.04 ± 6.75 | 46.08 ± 5.61 | 0.025 |

| RVED/LVED | 0.71 ± 0.21 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 0.003 |

| TRV, m/s | 4.02 ± 0.65 | 3.60 ± 0.58 | 0.002 |

| LVEF, % | 64.76 ± 4.95 | 66.80 ± 4.82 | 0.079 |

| TAPSE, mm | 19.68 ± 4.19 | 20.12 ± 3.10 | 0.660 |

| Haemodynamics | |||

| SvO2, % | 67.46 ± 6.82 | 70.91 ± 4.89 | 0.023 |

| mRAP, mmHg | 8.06 ± 5.07 | 7.50 ± 2.87 | 0.559 |

| mPAP, mmHg | 41.20 ± 11.00 | 35.96 ± 10.48 | 0.002 |

| PAWP, mmHg | 10.39 ± 2.20 | 10.83 ± 2.83 | 0.477 |

| Cardiac index, L/(min.m2) | 2.96 ± 0.86 | 3.17 ± 0.79 | 0.328 |

| PVR, wood units | 7.60 ± 4.46 | 5.28 ± 2.56 | 0.004 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| ALT, IU/L | 20.68 ± 12.90 | 17.16 ± 9.12 | 0.119 |

| AST, IU/L | 26.68 ± 7.67 | 26.28 ± 6.99 | 0.824 |

| TBil, μmol/L | 15.45 ± 6.69 | 14.67 ± 6.90 | 0.567 |

| CREA, μmol/L | 88.18 ± 17.56 | 86.04 ± 16.93 | 0.172 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 92.75 ± 18.38 | 95.14 ± 17.91 | 0.202 |

- Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or number (percentage). Significant P values (P < 0.05) are bolded.

- ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CREA, creatinine; eGFR, Estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; mRAP, mean right atrial pressure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PAWP, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RVED/LVED, right ventricular end-diastolic diameter/left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; 6MWD, 6-min walk distance; SVO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation; TBil, total bilirubin; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity; WHO FC, World Health Organization functional class.

Predictors of balloon pulmonary angioplasty success on total occlusion

We further explored predictors of BPA success in total occlusion at the attempt level. Univariable logistic regression revealed that the type of total occlusion was associated with treatment success (round-head occlusion/pointed-head occlusion, OR 24.500, 95% CI 2.498–240.318, P = 0.006; orifice occlusion/pointed-head occlusion, OR 42.000, 95% CI 3.034–581.434, P = 0.005) (Table S1). After adjusting for confounders in multivariable logistic regression, the type of total occlusion was still independently associated with treatment success (Table S2).

Discussion

In the current study, we proposed a novel morphology-specific classification of total occlusion in CTEPH, namely, pointed-head, round-head, and orifice occlusion, which has a significant impact on BPA success and complications. Pointed-head occlusion had the highest success rate, lowest procedure demand and treatment complexity, whereas orifice occlusion had the highest procedure demand and treatment complexity, as well as the lowest success and highest complication rates.

Total occlusion is challenging and is commonly considered for BPA after all non-occluded lesions are addressed. Kawakami et al. reported that the success rate of total occlusion was 53%, which was significantly lower than that for non-occluded lesions (nearly 100%),3 and similar results were observed by Taniguchi.11 In the present study, the success rate was 70.73%. We classified total occlusion into three types and illustrated the treatment strategy in detail, which could guide clinicians in future treatment. BPA was successful in most cases of pointed-head occlusion, without complications. The success rate declined significantly with the increased size of the occlusive cap, and over 50% of the BPA attempts failed in orifice occlusion. Compared with other types of total occlusion, pointed-head occlusion can be passed relatively easily using a soft-tip wire and subsequently dilated by a balloon. In contrast, soft-tip wires often fail to penetrate round-head occlusions, which warrants the use of a guide extension catheter and a harder tip catheter. Treating orifice occlusion is the most challenging, warranting not only a stronger backup but also more complex treatment strategies, including the use of microcatheters and parallel wires. Therefore, failure to pass a wire across an occlusive segment may suggest a ‘harder tip’ wire may be a good next step.

The varied BPA success rates and technical difficulties in the three types of occlusions were attributable to several factors, including varied backup forces provided by tissue surrounding lesion, matching degrees between the occlusive cap and the tip of the wire as well as thrombus chronicity and histology of lesions. In pointed-head occlusion, the tip of the wire matches the size of the occlusive cap and both sides of the occlusive cusp provide support for wire manipulation. Therefore, the tip of the soft guidewire can be fixed to the occlusive cap and subsequently passed through the lesion. However, in round-head occlusion, the tip of the wire often bends at the occlusive cap, failing to fix in the occlusive cap. Moreover, the lack of support from both sides of the lesion increases the difficulty of wire manipulation as the force of the interventionists could not be transmitted to the tip of the wire, making the tip of the wire shake during the intervention. Therefore, the primary guidewire often fails in round-head occlusion, and the simultaneous application of a hard-tip guidewire and a microcatheter is needed to provide sufficient backup force. In cases of orifice occlusion, engaging the guidewire into occluded vessels is the most challenging because the origin of the occlusion is difficult to recognize, and the course of the guidewire is parallel to the occlusive cap. Interventional cardiologists could only explore the entrance of the occluded vessels by placing the tip of the wire in the lumen based on experience and anatomical anticipation. Even when successfully identifying the origin of the occluded vessels, positioning the guidewire coaxially with the occluded vessels is extremely difficult, and there is barely any backup force for subsequent wire manipulation. Thus, the assistance by the microcatheter and parallel wire is necessary to provide sufficient backup force. Owing to the parallel relationship between the guidewire and the occlusive cap, it is common for the tip of the wire to enter the subintimal space and cause dissection. Therefore, it is advisable for experienced interventional specialists to attempt orifice occlusion with caution to avoid complications.

The location, underlying pathology and components of the occlusion may also contribute to the different BPA outcomes in the three types of total occlusions. Compared with other types, the location of orifice occlusions was more proximal in this study, which is more suitable for PEA.12 PEA can effectively remove all occlusive materials, including organized thrombi, fibrous tissue, thickened intima, and media in the proximal arteries.13 Contrary to PEA, BPA does not remove deposits on arteries, but compresses the occlusive material using a balloon to the artery wall and stretches the involved arteries to revascularize the occlusion. The proximal arteries lesions, which are commonly observed in orifice occlusions, are often occluded by organized thrombi, fibrous intima, and muscularized media suffer from high peripheral resistance due to post-obstructive microvasculopathy.12, 14 Although BPA can revascularize occluded arteries by balloon compression, the elastic features of the remodelled large arteries and peripheral microvasculopathy could contribute to restenosis and reocclusion, as observed in the current study. In contrast, distally occluded arteries, which are commonly observed in pointed-head occlusions, have less organized thrombi and less extent of vascular muscularization.14 The canal created by BPA remained patent at follow-up. Therefore, compared with that of round-head and orifice occlusions, occlusive plug of pointed-head occlusions is more likely to be just softer and less organized material.

Subintimal dissection was the most common complication when intervening with totally occluded lesions. When complications occurred, we stopped the performance immediately. The course of pointed-head occlusion and round-head occlusion vessels is relatively easy to determine, while the course of orifice occlusion vessels is difficult to determine, so the guide wire is easily mistaken into the subintima and dissection is likely to occur, leading to failure of treatment. Subintimal dissection in totally occluded lesions did not warrant specific treatments and the dissection resolved spontaneously after wire retrieval. Similar results have been reported by Inami et al.15 and Steinberg et al.16 With increasing experience, BPA for total occlusion may yield greater efficacy and haemodynamic benefits. The current study had a relatively large sample size for treating total occlusion and is the first to comprehensively illustrate the features and treatment strategies of total occlusion.

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the number of BPA attempts for total occlusion was relatively small, and not all total occlusions were addressed. Most patients did not complete the BPA procedures and will continue with treatment in the future. Second, the pathological characteristics pertaining to each type of lesion were unavailable in this study; therefore, the exact composition of each category of total occlusion lesion remains elusive, which warrants further investigation. Third, the cut-off for pointed-head occlusion was defined as 5 mm, which was predominantly according to our experience and might be arbitrary. We defined 5 mm as the cut-off value because it was approximately twice the size of the 8 Fr catheter's diameter. Fourth, intervention for orifice occlusion is challenging, with a low success rate, which warrants future studies to explore better techniques to revascularize such occlusions. Fifth, in this study, not all of the total occlusion lesions were addressed. Total occlusions in patients who had high mPAP and PVR were not addressed due to the high risk of failure and complications. Therefore, we may have underestimated the incidence of complications in occlusive lesions.

In conclusion, the morphology of the occlusions exerts a substantial influence upon BPA success and complication rates. The rates of failure and the level of technical complexity of BPA progressively heightened in the subsequent sequence: pointed-head, round-head, and orifice occlusion. We recommend that clinicians address total occlusion based on the lesion type. The information in this study could be used to improve the outcomes of BPA and help clinicians in treating total occlusions with confidence.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This research article was supported by Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (Grant No. Z181100001718200); Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 7202168); Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (Grant Nos 2020-I2M-C&T-B-055 and 2021-I2M-C&T-B-032); “Double First-Class” Discipline Construction Fund of Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 2019E-XK04-02); the Capital's Funds for Health Improvement and Research (Grant No. 2020-2-4033 and 2020-4-4035); National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Grant No. 2022-GSP-GG-35); and the Artificial Intelligence and Information Technology Application Fund of Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 2022-AI01). The funding sponsors had no involvement in the current study.