The interaction between physical frailty and prognostic impact of heart failure medication in elderly patients

Abstract

Aims

Frailty is highly prevalent and associated with poor prognoses in elderly patients with heart failure (HF). However, the potential effects of physical frailty on the benefits of HF medications in elderly patients with HF are unclear. We aimed to determine the influence of physical frailty on the prognosis of HF medications in elderly patients with HF with reduced and mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFr/mrEF).

Methods and results

From the combined HF database of the FRAGILE-HF and Kitasato cohorts, hospitalized HF patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction < 50% and age ≥ 65 years were analysed. Patients treated with or without renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) and beta-blockers at discharge were compared. Physical frailty was defined by the presence of ≥3 items on the Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality rate. Among the 1021 enrolled patients, 604 patients (59%) received both RAASi and beta-blockers, and 604 patients (59%) were diagnosed as physically frail. Patients receiving both RAASi and beta-blockers showed a significantly lower 1 year mortality than those not receiving either, even after adjusting for covariates (hazard ratio: 0.50, 95% confidence interval: 0.34–0.75). This beneficial effect of both medications on 1 year mortality was comparable between patients with and without physical frailty (hazard ratio: 0.53 and 0.51, respectively; P for interaction = 0.77).

Conclusions

The presence of physical frailty did not interact with the beneficial prognostic impact of RAASi and beta-blocker combination therapy in elderly patients with HFr/mrEF.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is an expanding global public health problem associated with a high mortality rate.1 The number of elderly patients with HF has been increasing, particularly in countries with ageing societies.2 Frailty is a syndrome characterized by increased vulnerability to stressors and diminished physiological reserves.3 The prevalence of both frailty and HF increases with age, and these two conditions are strongly associated with systemic multisystem dysfunction.4 As a result, physical frailty is highly prevalent in elderly patients with HF and is a strong predictor of early disability and mortality.5

The prognostic advantages of treatment with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers, together with beta-blockers in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40%] and mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF; LVEF = 40–49%) have been validated in numerous trials.6-11 Moreover, previous studies have shown that the combination of RAASi and beta-blockers shows prognostic superiority over treatment with either or none of these drugs in terms of all-cause mortality.12 On the other hand, the prescription rate of these HF medications has been reported to be lower in HFrEF patients with frailty than in those without,13 and this can be partially attributed to the lack of clarity over the comparable effectiveness of these medications for HFr/mrEF in patients with and without frailty. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the influence of physical frailty on the prognosis of combination therapy for HF in elderly patients with HFr/mrEF.

Methods

Study design and population

We used the combined HF database of the FRAGILE-HF and Kitasato cohorts, which included patients hospitalized for decompensation of HF. The FRAGILE-HF study was a multicentre observational cohort study that included hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with decompensation of HF who could ambulate at discharge between September 2016 and March 2018. The main objective of the FRAGILE-HF study was to evaluate the prevalence and prognostic impact of multifrailty domains in patients with HF.14 The Kitasato cohort was a single-centre retrospective observational study that included elderly patients with HF whose usual gait speed was investigated during inpatient cardiac rehabilitation at Kitasato University Hospital between January 2008 and December 2017. The study conforms with the principles outlined with the Declaration of Helsinki and Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. Because this was an observational study without invasive procedures or interventions, written informed consent was waived under the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, issued by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of each participating hospital.

From the combined database of these two cohorts, we extracted patients aged ≥65 years with HFrEF and HFmrEF defined by echocardiographic examinations that were performed during the index hospitalization and stratified them according to the prevalence of physical frailty. The presence/absence of physical frailty was defined using the Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria, which were based on the Fried phenotype model that is suitable for elderly Japanese patients and has already been validated in previous reports15, 16 (Supporting Information, Table S1). On the Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria, a score of 0 is classified as robust, scores of 1–2 are categorized as prefrail, and a score of 3 or more is classified as frail. In this study, patients showing ≥3 items were defined as being complicated and physically frail. We compared the baseline clinical, physiological, and echocardiographic findings and the prognosis after discharge between patients who received combination therapy of RAASi and beta-blockers and those who did not in those with and without physical frailty.

Outcomes

The endpoint of this study was death from any cause within 1 year of discharge. The patients visited clinics at least once every 3 months or more frequently according to their medical needs. For patients who did not undergo follow-up examinations in clinics, prognostic data were collected by telephone interviews from the family or from the medical records of other medical facilities that treated the patient.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean and standard deviation for normally distributed variables and as median with interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages. Variables were transformed into a logarithmic scale for further analyses if necessary. Group differences were evaluated using the χ2 or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables and Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Event-free survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier survival method, and differences between groups were compared using log-rank statistics. Regarding the primary outcome of all-cause death, we used the Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) risk score as an adjustment variable because its prognostic efficacy has already been validated in Japanese patients with HF.17 The GWTG-HF risk score includes age, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, blood urea nitrogen and sodium levels, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and race.18 In addition, log-transformed B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level, LVEF, anaemia status, and New York Heart Association class were used to adjust variables in a multivariable prognostic model for the outcome of all-cause death because these variables have been proven to improve model performance when added to the GWTG-HF risk score.18 A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with R, Version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; ISBN 3-900051-07-0; URL http://www.R-project.org).

Results

During the study period, there were 1332 hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years in the FRAGILE-HF study and 669 hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years in the Kitasato cohort. We excluded 926 patients with LVEF ≥ 50% and 54 patients with missing data for the Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria and/or medications at discharge. Finally, 1021 patients were included in the study. Survival analysis was performed on 1003 patients because 18 patients had missing follow-up data.

Baseline profiles

The median age of the entire study population was 78 years, and 63.6% of the patients were men. The 1021 patients included 604 (59.2%) patients with physical frailty and 417 (40.8%) without physical frailty. There were 729 patients (71%) with HFrEF and 292 patients (29%) with HFmrEF. The proportion of men among patients with physical frailty was lower than that among those without physical frailty. Patients with physical frailty were older and more likely to have lower body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, haemoglobin levels, and albumin levels and higher blood urea nitrogen levels and BNP levels than those without physical frailty (Table 1).

| Variables | Frailty (−) | Frailty (+) | P value | RAASi and beta-blockers (−) | RAASi and beta-blockers (+) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 417 | n = 604 | n = 323 | n = 698 | |||

| Age (years) | 76 [71–81] | 79 [73–85] | <0.001 | 81 [75–86] | 77 [71–82] | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 288 (69.1%) | 362 (59.9%) | 0.004 | 197 (61.0%) | 453 (64.9%) | 0.255 |

| NYHA III–IV | 34 (8.6%) | 107 (18.4%) | <0.001 | 52 (16.6%) | 89 (13.4%) | 0.214 |

| Current smoker | 51 (12.3%) | 63 (10.5%) | 0.424 | 25 (7.8%) | 89 (12.9%) | 0.022 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.7 [20.1–23.3] | 20.8 [19.0–22.6] | <0.001 | 20.7 [18.9–22.4] | 21.4 [19.7–23.1] | 0.006 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 109 [100–117] | 107 [98–116] | 0.024 | 111 [102–119] | 106 [97–115] | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 62 [56–67] | 59 [53–65] | <0.001 | 61 [56–66] | 60 [54–66] | 0.035 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 72 [64–80] | 73 [66–80] | 0.384 | 73 [65–80] | 73 [66–80] | 0.672 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 33 [27–40] | 33 [26–41] | 0.701 | 35 [29–43] | 32 [26–40] | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Heart failure | 213 (51.1%) | 341 (56.6%) | 0.097 | 182 (56.3%) | 372 (53.4%) | 0.412 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 152 (36.5%) | 227 (37.6%) | 0.763 | 136 (42.1%) | 243 (34.8%) | 0.03 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 43 (10.3%) | 73 (12.1%) | 0.437 | 47 (14.6%) | 69 (9.9%) | 0.038 |

| Diabetes | 156 (37.4%) | 231 (38.2%) | 0.838 | 94 (29.1%) | 293 (42.0%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 283 (67.9%) | 413 (68.4%) | 0.917 | 212 (65.6%) | 484 (69.3%) | 0.267 |

| Prescription at discharge | ||||||

| ACEi/ARB | 331 (79.4%) | 460 (76.2%) | 0.257 | 93 (28.8%) | 698 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 356 (85.4%) | 511 (84.6%) | 0.804 | 169 (52.3%) | 698 (100%) | <0.001 |

| MRA | 224 (53.7%) | 316 (52.3%) | 0.707 | 134 (41.5%) | 406 (58.2%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data at discharge | ||||||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.5 [11.5–13.5] | 11.8 [10.8–12.8] | <0.001 | 11.7 [10.7–12.7] | 12.2 [11.2–13.2] | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 [3.3–3.8] | 3.4 [3.1–3.6] | <0.001 | 3.4 [3.1–3.6] | 3.5 [3.2–3.7] | 0.042 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 25 [20–34] | 28 [20–37] | 0.004 | 26 [20–35] | 27 [20–36] | 0.724 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.16 [0.94–1.59] | 1.23 [0.94–1.72] | 0.112 | 1.24 [0.94–1.65] | 1.20 [0.94–1.67] | 0.837 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 52 [36–65] | 47 [31–64] | 0.067 | 49 [34–65] | 49 [32–64] | 0.719 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 139 [137–141] | 138 [136–140] | 0.031 | 139 [137–141] | 138 [136–140] | 0.022 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 374 [185–684] | 435 [229–824] | 0.002 | 406 [191–716] | 395 [211–810] | 0.346 |

- ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NYHA, New York Heart Association classification; RAASi, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors.

- Values are presented as median [interquartile range], n (%), or mean (standard deviation).

A total of 698 patients (68.4%) were prescribed both RAASi and beta-blockers, and 323 patients (31.6%) were prescribed either RAASi or beta-blockers or none. Patients receiving combination therapy with HF medication were younger and likely to have higher body mass index, lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures, higher haemoglobin levels, higher albumin levels, and lower LVEF than those who did not (Table 1). Renal function was not significantly different between patients with and without combination therapy.

In the population without frailty, patients receiving combination therapy were younger and more likely to have lower systolic blood pressures and LVEF and higher haemoglobin levels and BNP levels than those not receiving combination therapy (Supporting Information, Table S1). In the population with frailty, patients receiving combination therapy were younger and more likely to have lower systolic blood pressures and LVEF and higher body mass index and haemoglobin levels than those not receiving combination therapy.

Prognoses

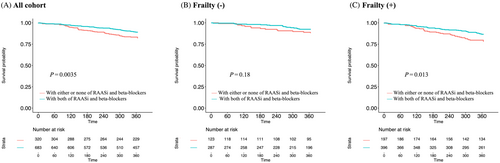

Of the entire study population, 121 patients (12%) died from any reason; 88 (15%) died in the frailty group (n = 604) and 33 (8%) died in the non-frailty group (n = 417) during the observational period. From the perspective of medication, 54 patients (17%) died in the population without combination therapy (n = 323) and 67 (10%) died in the population with combination therapy (n = 698). Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that patients on combination therapy at discharge showed a significantly lower 1 year all-cause mortality than those without combination therapy (log rank, P = 0.0035; Figure 1). Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that combination therapy was associated with lower mortality even after adjustment for covariates [hazard ratio (HR): 0.50, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.34–0.75; Table 2].

| Univariate Cox | Adjusted for GWTG risk score + log BNP + LVEF + anaemia + NYHA class | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| 1. Entire cohort | ||||||

| RAASi and beta-blockers | 0.59 | 0.41–0.84 | 0.004 | 0.50 | 0.34–0.75 | <0.001 |

| 2. Patients without frailty | ||||||

| RAASi and beta-blockers | 0.62 | 0.31–1.25 | 0.181 | 0.51 | 0.22–1.17 | 0.112 |

| 3. Patients with frailty | ||||||

| RAASi and beta-blockers | 0.59 | 0.39–0.90 | 0.014 | 0.53 | 0.33–0.83 | 0.006 |

- BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CI, confidence interval; GWTG, Get With the Guidelines; HR, hazard ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association classification; RAASi, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of patients without physical frailty showed that combination therapy was marginally but not significantly associated with a better prognosis in comparison with patients who were not receiving combination therapy (log rank, P = 0.18; Figure 1). Similarly, the results of multivariable Cox regression showed a point estimation of HR of 0.51, which did not reach the statistical threshold after adjustment for covariates (95% CI: 0.22–1.17, P = 0.112; Table 2). In contrast, among patients with physical frailty, combination therapy was significantly associated with a lower mortality rate in Kaplan–Meier analysis (log rank, P = 0.013; Figure 1), as well as in the multivariable Cox regression model after adjustment for covariates (HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.33–0.83, P = 0.006; Table 2). We further assessed whether the presence/absence of frailty modified the association between the combination therapy and mortality by using an interaction term and found no statistically significant interaction between the presence/absence of frailty and the association between combination therapy at discharge and mortality (P for interaction = 0.77; Table 2). In patients with HFrEF, the HR of combination therapy for all-cause death was 0.77 (HR: 0.49–1.22, P = 0.27) and the interaction between combination therapy and frailty was not statistically significant (P for interaction = 0.83). However, in patients with HFmrEF, the HR of the combination therapy for all-cause death was 0.35 (HR: 0.18–0.69, P = 0.002) and the interaction between combination therapy and frailty was not statistically significant (P for interaction = 0.97).

Discussion

Principal findings of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the influence of physical frailty as a comorbidity of HF on the effects of HF medication on the prognosis in elderly hospitalized patients with HFr/mrEF. Combination therapy at discharge was associated with better 1 year mortality in HFr/mrEF patients aged ≥65 years. Although the combination was significantly associated with lower mortality in those with physical frailty but not in those without, no significant interaction was found between the presence/absence of frailty and the association between combination therapy and mortality in patients with HFr/mrEF.

HF medications in elderly patients with HF

Elderly patients constitute a large proportion of all hospitalized patients with HF because HF is prevalent primarily in older patients.19 Indeed, a study from the Japanese Cardiac Registry of Heart Failure in Cardiology reported that nearly 30% of hospitalized patients with HF were aged ≥80 years.20 Thus, the therapeutic management of elderly patients with HF is a worldwide concern. However, elderly patients with HF have often been excluded from previous large clinical trials for several reasons, such as old age or multiple comorbidities. Nevertheless, a few studies have evaluated the efficacy of HF medications in elderly patients. A randomized controlled trial, SENIORS, which assessed the effects of beta-blockers in HFrEF patients aged >70 years, indicated that nebivolol reduced a composite of all-cause death and cardiovascular hospital admission in these patients.21 A sub-analysis from a randomized controlled trial, CHARM, which included patients aged 60–69 years (31%), 70–79 years (33%), and 80 years (9%), indicated that candesartan reduced the risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization irrespective of age.22 Conversely, some studies have claimed that these medications and their combinations were not effective in elderly patients with HF.23, 24 Due to the limited evidence and diverse comorbidities in elderly patients with HF, RAASi and beta-blockers were prescribed less frequently to older patients with HF in clinical practice, according to previous reports.24, 25

In the present cohort study, including patients with a median age of 78 years and with diverse comorbidities, the percentage of patients receiving combination therapy, in which both drugs were recommended by guidelines for patients with left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction, was also limited (68%), while the combination therapy was associated with better 1 year mortality even after adjusting for covariates. Numerous factors are associated with the prognosis of elderly patients with HF, and the prognostic role of therapies that are generally recommended for elderly patients with HF should be further investigated because no specific recommendations are available for this population.

HF medications in frail patients with HF

Physical frailty is a common condition in patients with HF. In the current cohort study, which consisted of two large cohorts in Japan, 59% of hospitalized patients with LV systolic dysfunction aged >65 years had physical frailty. HF and physical frailty share common biological mechanisms, and the relationship between them is bidirectional, forming a vicious cycle.26 Indeed, HF patients with physical frailty had a worse prognosis than those without physical frailty.5

The prognostic advantages of RAASi and beta-blocker in patients with HFrEF/mrEF have been validated in numerous trials.6-11 However, the mechanism underlying the effects of these medications in patients with physical frailty remains unclear. Regarding RAASi, there is little evidence that the administration of ACEi in patients with physical frailty may have a protective effect on muscle. Onder et al. reported that ACEi slowed the decline in muscle strength in elderly women without HF.27 This may be due to the positive effect of ACE inhibition on inflammation and insulin resistance, which was elevated in frail patients.28 Regarding beta-blockers, their effects on muscles are also unclear. The adrenergic signalling pathway stimulates an anabolic response in skeletal muscle via increased protein synthesis and decreased degradation.28 Although beta-blockers would not benefit skeletal muscle from this point of view, a previous study reported that carvedilol enhanced skeletal muscle contractility in a murine model.29 As mentioned above, the relationship between HF medications and skeletal muscle has been investigated; however, the direct relationship between HF medications and the prognosis of elderly patients with HFr/mrEF with frailty remains unclear to date. Our study suggests that physical frailty does not significantly affect the prognostic advantage of combination therapy in elderly patients with HFr/mrEF. This result suggests that the presence of frailty alone does not justify the withdrawal or non-prescription of medications that are generally recommended for patients with HF.

Limitations

The current study had some limitations. First, owing to the nature of an observational cohort study, the initiation of HF medications was at the discretion of the attending physicians, and we did not consider whether patients were naïve to medications at the time of hospitalization or had previously received them. Although we adjusted for covariates, unmeasured and unknown variables may have influenced the results. Second, we only investigated the influence of physical frailty on the effectiveness of RAASi, including ACEi and angiotensin II receptor blockers, and beta-blockers. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors, and vericiguat were not investigated in this study. The prescription rate of MRAs was lower than that of RAASi and beta-blockers in the current study, possibly due to limiting factors such as renal dysfunction and hyperkalaemia.25 In particular, these limiting factors are more prevalent in elderly patients, and the backgrounds of patients who received MRA and those who did not were significantly different. Thus, we limited the investigation to HF medications, including RAASi and beta-blockers. Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors, and vericiguats were not approved for patients with HF during the study period. Elderly patients may receive further prognostic benefits from these new drugs that have already been verified to reduce adverse events in younger adults. Third, we did not consider the dosages of the medications at discharge. Fourth, we evaluated physical frailty only once during hospitalization, and no information was obtained after discharge. Finally, physical frailty was evaluated based on the Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria, which were created based on the Fried phenotype model suitable for elderly Japanese patients. Thus, the results of this study may not be directly applicable to other countries. On the other hand, one of the strengths of this study was that physical frailty was measured by a unified evaluation method, which has been validated in Japanese patients previously during hospitalization. Thus, despite the limitations, the results of this study provide important information that may be beneficial in clinical practice regarding the management of elderly hospitalized patients with HF because randomized controlled studies may be difficult to conduct in such elderly high-risk populations.

In conclusion, physical frailty did not interact with the prognostic effect of HF medications, including RAASi and beta-blockers, in elderly patients with HFr/mrEF.

Conflict of interest

Y.M. is affiliated with a department endowed by Philips Respironics, ResMed, Teijin Home Healthcare, and Fukuda Denshi and received an honorarium from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. T.K. is affiliated with a department endowed by Philips Respironics, ResMed, Teijin Home Healthcare, and Fukuda Denshi. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The FRAGILE-HF study was supported by Novartis Pharma Research Grants and a Japan Heart Foundation Research Grant.