Risk of in-hospital life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia or death after ST-elevation myocardial infarction vs. the Takotsubo syndrome

Abstract

Aims

The risk of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (LTVA) has been reported to be lower in Takotsubo syndrome (TS) compared with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, the extent to which these differences relate to the fact that most patients with TS are women (who have a lower risk of LTVA) and a relatively larger proportion of patients with STEMI are men is incompletely understood. We aimed to investigate the risk of LTVA or death in sex-matched and age-matched patients with TS, anterior STEMI, and non-anterior STEMI.

Methods and results

We systematically reviewed the charts of all patients with TS who were treated at Sahlgrenska University Hospital (Gothenburg, Sweden) between 2008 and 2019. A total of 155 patients with confirmed TS (according to the European Society of Cardiology diagnostic criteria for TS) were sex-matched and age-matched 1:1:1 to patients with anterior and non-anterior STEMI. Baseline characteristics and in-hospital outcomes were recorded directly from the patient charts for all patients, and all admission electrocardiographs were analysed. The primary outcome was the composite of death or LTVA [defined as sustained ventricular tachycardia (>30 s) or ventricular fibrillation] within 72 h. The risk of LTVA or death within 72 h after admission was considerably lower in TS (2.6%) vs. anterior STEMI (14%; P = 0.002) and non-anterior STEMI (9.0%; P = 0.02), despite similar or greater risks of acute heart failure, and similar risks of cardiogenic shock. Compared with STEMI, TS was associated with a lower risk of sustained and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation.

Conclusions

In a predominantly female age-matched and sex-matched cohort of patients with TS, anterior STEMI, and non-anterior STEMI, the adjusted risk of in-hospital LTVA or death was considerably lower in TS compared with STEMI, despite similar or greater risk of acute heart failure and similar risk of cardiogenic shock.

Introduction

Takotsubo syndrome (TS) and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are both acute cardiac syndromes characterized by rapid onset of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction that may cause life-threatening heart failure and arrhythmias. Although the presenting symptoms, non-invasive test results and complications are similar in TS and STEMI, the pathophysiology is different.1, 2 Whereas STEMI is caused by an acute coronary occlusion that may result in a large myocardial infarction if timely revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention is not performed, TS is not caused by acute coronary occlusion per se and is self-limiting in most cases. Another striking difference between STEMI and TS is that STEMI is more common in men than women2-4 whereas approximately 9 out of 10 patients with TS are women.5, 6

Takotsubo syndrome was first regarded a benign syndrome, but recent studies suggest that mortality may be comparable in TS and STEMI.7-10 A potentially lethal complication of both TS and STEMI is ventricular arrhythmias,11, 12 and the extent of LV dysfunction is an important predictor of the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias in both STEMI and TS.13-17 However, despite the fact that LV dysfunction is often more pronounced in TS than STEMI, the reported occurrence of ventricular arrhythmia in TS is lower than that reported for STEMI, suggesting that cardiac electrophysiology may be more stable in TS than STEMI.2, 11 However, it is important to note that among patients with STEMI, ventricular arrhythmias are more common in men than women,18 and most studies that compared the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and outcome in STEMI vs. TS had more men in their STEMI groups vs. the TS groups.7, 19, 20 It is also worth noting that the incidence of ventricular and other arrhythmias may differ between patients with anterior STEMI (in whom the large left anterior descending coronary artery is occluded) and patients with non-anterior STEMI (in whom the atrioventricular conduction system is more likely to be affected).

We sought to compare the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in strictly sex-matched and age-matched cohorts of patients with TS vs. anterior STEMI vs. non-anterior STEMI. We also assessed the relationship between patient-level risk factors and the risk of arrhythmia in patients with TS vs. STEMI.

Methods

Study cohort

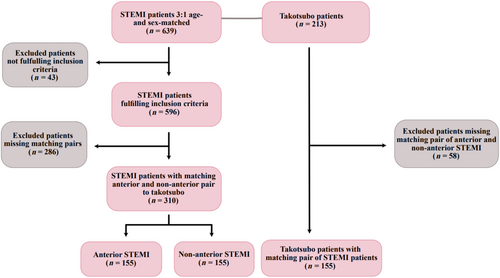

Patients who were admitted to Sahlgrenska University Hospital between January 2008 and January 2019 with suspected Takotsubo or STEMI were identified using the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. First, medical charts were reviewed for all patients with suspected Takotsubo. Patients who fulfilled the European Society of Cardiology diagnostic criteria for Takotsubo were included in the study (n = 213). All Takotsubo patients underwent coronary angiography to exclude acute coronary syndrome as the cause of cardiac dysfunction. The Takotsubo patients were matched by sex (perfect match) and age (within 2 years) to patients with STEMI. After chart review of all matched STEMI patients, one patient with confirmed anterior STEMI and one patient with confirmed non-anterior STEMI (both inclusion by European Society of Cardiology criteria) were selected per matching patient with Takotsubo. If a patient with Takotsubo could not be matched to one patient with anterior STEMI and one patient with non-anterior STEMI, none of these patients were included, resulting in a 1:1:1 matched cohort (n = 465, Figure 1).

Information regarding prior burden of arrhythmia, admission clinical variables, ongoing medical treatment including antiarrhythmic treatment, severity of acute heart failure (AHF), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), in-hospital arrhythmias, resuscitation at baseline and at hospital ward, and the occurrence of electro-cardioversion and defibrillation were collected from patient charts. Detailed information related to arrhythmias is documented by thorough review of continuous telemetry recordings three times per day at the cardiology clinic at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, as part of routine clinical care. Detailed information of arrhythmias and admission 12 lead electrocardiography (ECG) (<2 h after admission) were available for all patients. We reviewed angiography for all patients to obtain information on culprit vessel for the STEMI-cohort. Information on co-morbidities was obtained from Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry.

Endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint was the composite of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia [LTVA, defined as sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF)] or death within 72 h after hospital admission. The secondary endpoint was the composite of any VT or VF (VT/VF) or death within 72 h. Sustained VT was defined as VT with duration >30 s or requiring cardioversion. Significant bradycardia was defined as asystole lasting at least 10 s or atrioventricular block grade ≥ 2. AHF was defined as Killip class ≥ 2 and cardiogenic shock (CS) as Killip class 4. Prolonged QTc was defined as QTc > 440 ms for men and >460 ms for women, with QTc calculated using Basset's formula. T-wave-inversion was defined as a negative T-wave ≥ 1 mm in any lead except for aVR and V1.

Statistical analysis

Variables are presented across these three groups as mean ± standard deviations, median and interquartile range, or percentages for categorical variables; and compared using linear or logistic regression. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the adjusted association between Takotsubo vs. STEMI and outcomes. The following covariate set was used in the multivariable models: diabetes, current smoking, hypertension, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, and previous myocardial infarction. A random effect was included to account for the correlation within matched triplets.

This study complies with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study cohort consisted of a total of 155 patients with TS, 155 patients with anterior STEMI and 155 patients with non-anterior STEMI. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Additional details for patients with TS are presented in Table S1. In this sex-matched cohort, 91% (141/155) of patients in all three groups were female. Most baseline characteristics were similar between the groups, but patients with TS were less likely to smoke or have diabetes and had on average lower BMI than patients with STEMI. There were no differences in medications used at the time of admission, with the exception that patients with TS and anterior STEMI were less likely to be treated with beta blockers compared with non-anterior STEMI. Prior arrhythmia burden and ongoing treatment with anti-arrhythmic drugs (non-beta blocker) were similar between groups (Table 1). For the anterior STEMI-cohort, LAD and LCx were the culprit vessels in 94% and 4% of cases, respectively, and for the non-anterior STEMI-cohort, RCA and LCx were the culprit vessels in 72% and 20%, respectively. The remaining had combinations of either LAD, LCx, or RCA as culprit.

| Variable | Anterior STEMI N = 155 | Non-anterior STEMI N = 155 | Takotsubo N = 155 | P values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | ** | *** | P overall | ||||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 69 ± 13 | 69 ± 13 | 69 ± 13 | 0.99 | >0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Female sex % (n/N) | 91% (141/155) | 91% (141/155) | 91% (141/155) | >0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | >0.99 |

| BMI | 27 ± 4.6 | 26 ± 4.7 | 25 ± 4.8 | 0.86 | 0.0040 | 0.020 | 0.0026 |

| Diabetes % (n/N) | 11% (17/152) | 14% (21/148) | 4.5% (7/154) | 0.43 | 0.036 | 0.0060 | 0.011 |

| Diabetes, insulin | 5.3% (8/152) | 2.7% (4/148) | 1.3% (2/154) | 0.27 | 0.072 | 0.39 | 0.12 |

| Smoking | 24% (37/155) | 29% (45/155) | 11% (17/155) | 0.30 | 0.0034 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 45% (67/149) | 47% (69/148) | 42% (64/153) | 0.77 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.70 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 16% (23/144) | 21% (30/145) | 17% (25/150) | 0.30 | 0.87 | 0.38 | 0.53 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 9.0% (14/155) | 10% (16/155) | 6.5% (10/155) | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.52 |

| Previous PCI | 5.8% (9/155) | 6.5% (10/155) | 4.5% (7/155) | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.75 |

| Previous VT | 0.60% (1/155) | 0.0% (0/155) | 0% (0/155) | 0.32 | 0.32 | >0.99 | 0.37 |

| Previous atrial fibrillation or flutter | 4.5% (7/155) | 5.2% (8/155) | 9.7% (15/155) | 0.79 | 0.084 | 0.14 | 0.32 |

| Previous significant bradycardia | 0.0% (0/155) | 0.0% (0/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | >0.99 | 0.082 | 0.082 | 0.049 |

| Previous AV block ≥ 2 | 0.0% (0/155) | 0.0% (0/155) | 0.6% (1/155) | >0.99 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.37 |

| Hospitalized for at least 72 ha | 86% (128/149) | 85% (126/149) | 83% (126/152) | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| Presenting symptoms and signs | |||||||

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 85 ± 21 | 70 ± 20 | 89 ± 19 | <0.001 | 0.11 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 141 ± 27 | 135 ± 29 | 135 ± 27 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.98 | 0.092 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 86 ± 18 | 80 ± 17 | 82 ± 17 | 0.0054 | 0.0409 | 0.7832 | 0.0048 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 95 ± 5.0 | 96 ± 5.7 | 94 ± 7.6 | 0.49 | 0.082 | 0.0033 | 0.0044 |

| Angina % (n/N) | 92% (143/155) | 94% (145/155) | 73% (110/150) | 0.66 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnoea | 14% (22/155) | 16% (24/155) | 30% (45/150) | 0.75 | 0.0011 | 0.0028 | <0.001 |

| Syncope | 3.9% (6/155) | 4.5% (7/155) | 7.3% (11/150) | 0.78 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| Killip Class ≥2 | 26% (40/155) | 21% (32/155) | 32% (/155) | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.020 | 0.066 |

| Killip Class 4 | 3.9% (6/155) | 5.8% (9/155) | 5.2% (8/155) | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.80 | 0.73 |

| Electro-cardioversion | 2.6% (4/155) | 3.2% (5/155) | 2.6% (4/155) | 0.74 | >0.99 | 0.74 | 0.092 |

| Defibrillation | 9.7% (15/155) | 4.5% (7/155) | 1.3% (2/155) | 0.077 | 0.0012 | 0.091 | 0.0035 |

| CPR at baseline | 9.0% (14/155) | 3.9% (6/155) | 1.3% (2/155) | 0.072 | 0.0080 | 0.17 | 0.0041 |

| CPR at hospital ward | 4.5% (7/155) | 1.9% (3/154) | 0.0% (0/155) | 0.27 | 0.0074 | 0.13 | 0.048 |

| Admission QTc (ms) | 442 ± 36 | 431 ± 31 | 449 ± 58 | 0.043 | 0.49 | 0.0011 | 0,0014 |

| Long QTc % (n/N) | 47% (73/154) | 32% (48/152) | 65% (101/155) | 0.0049 | 0.0018 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| QTc > 500 ms | 3.9% (6/154) | 2.0% (3/152) | 4.5% (7/155) | 0.33 | 0.79 | 0.22 | 0.42 |

| T-wave inversion | 51% (79/155) | 84% (130/154) | 44% (68/155) | <0.001 | 0.21 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Femoral access | 31% (48/155) | 39% (60/155) | 25% (39/155) | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.011 | 0.036 |

| LVEF at admission | 44 ± 11 | 52 ± 9.9 | 42 ± 9.8 | <0.001 | 0.27 | <0,001 | <0.001 |

| Home medications % (n/N) | |||||||

| Statins | 12% (19/155) | 18% (28/155) | 14% (21/149) | 0.16 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 0.34 |

| P2Y12 antagonist | 0.60% (1/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | 1.3% (2/149) | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.59 |

| Aspirin | 16% (24/155) | 21% (32/155) | 15% (23/149) | 0.24 | 0.99 | 0.24 | 0.39 |

| OAC/Warfarin | 3.9% (6/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | 6.0% (9/149) | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.081 | 0.17 |

| Beta-blockers | 23% (36/155) | 34% (52/155) | 18% (27/149) | 0.045 | 0.27 | 0.0025 | 0.0069 |

| ACEI/ARB | 21% (32/155) | 21% (33/155) | 28% (42/149) | 0.89 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.24 |

| Mineralocorticoid antagonist | 1.9% (3/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | 2.7% (4/148) | >0.99 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.88 |

| Diuretics | 13% (20/155) | 18% (28/154) | 10% (15/147) | 0.20 | 0.46 | 0.051 | 0.13 |

| Calcium antagonists | 12% (19/155) | 16% (24/155) | 9.4% (14/149) | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.27 |

| Antiarrhythmic agents (non-beta blocker) | 0% (0/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | 1.3% (2/149) | 0.082 | 0.15 | 0.68 | 0.24 |

- ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; long QTc, QTc > 440 ms for men and >460 ms for women; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OAC, oral anticoagulants; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; significant bradycardia, bradycardia with syncope or requiring pacemaker implantation; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

- a Patients who survived 72 h.

- * Anterior STEMI vs. non-anterior STEMI.

- ** Takotsubo vs. Anterior STEMI.

- *** Takotsubo vs. non-anterior STEMI.

Presenting symptoms and signs

ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients (anterior and non-anterior) were more likely to present with angina, whereas TS-patients were more likely to present with dyspnoea. Patients with TS had on average lower oxygen saturation and lower LVEF on admission and were significantly more likely to develop AHF than patients with non-anterior STEMI. However, patients with TS were not significantly more likely than patients with anterior STEMI to develop AHF and were not significantly more likely than patients with anterior or non-anterior STEMI to develop cardiogenic shock. Among patients with TS, there was no significant difference in the incidence of AHF among patients with atrial fibrillation within 72 h [3/15 (20.0%)] and patients without atrial fibrillation within 72 h [47/140 (33.6%), P = 0.29]. Admission QTc was longer in anterior STEMI and TS compared with non-anterior STEMI. Long QTc was most common in TS (65%), followed by anterior STEMI (47%) and non-anterior STEMI 32% with significant differences across all three groups. In non-anterior STEMI, heart rate at admission was lower when compared with anterior STEMI and TS. The frequency of T-wave inversion at admission was similar in anterior STEMI and TS but more frequent in non-anterior STEMI.

Clinical outcomes

Of 465 patients, 15 died within 72 h. Of the 450 patients who survived the 72 h period, 84% were continuously monitored for 72 h. The remaining 16% were low risk patients who were discharged before 72 h. There were no differences between groups in length of continuous monitoring. Patients with TS were considerably less likely to develop LTVA within 72 h of admission than patients with STEMI (Table 2). However, there were no significant differences in the crude 72 h rate of death. When patients with TS were compared with all patients with STEMI (anterior and non-anterior), patients with Takotsubo did not have a statistically significantly lower incidence of death [3/155 (1.9%) vs. 12/310 (3.9%); P = 0.27]. Patients with TS were less likely to develop significant bradycardia or AV-block ≥2 when compared with non-anterior STEMI but not compared with anterior STEMI (Table 2). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation were less common in TS compared with anterior STEMI.

| Variable | Anterior STEMI N = 155 | Non-anterior STEMI N = 155 | Takotsubo N = 155 | P values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | ** | *** | P overall | ||||

| Within 72 h | |||||||

| LTVA or death | 14% (21/155) | 9.0% (14/155) | 2.6% (4/155) | 0.21 | 0.0015 | 0.023 | 0.0010 |

| Death | 3.9% (6/155) | 3.9% (6/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | >0.99 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.51 |

| LTVA | 10% (16/155) | 6.5% (10/155) | 0.6% (1/155) | 0.22 | 0.0056 | 0.025 | 0.00020 |

| Sustained VT | 6.5% (10/155) | 2.6% (4/155) | 0% (0/155) | 0.10 | 0.0013 | 0.044 | 0.0037 |

| VF | 6.5% (10/155) | 5.2% (8/155) | 0.6% (1/155) | 0.63 | 0.025 | 0.046 | 0.0087 |

| VT, VF, or death | 44% (68/155) | 50% (78/155) | 14% (22/155) | 0.26 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Death | 3.9% (6/155) | 3.9% (6/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | >0.99 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.51 |

| VT or VF | 41% (63/155) | 48% (75/155) | 12% (19/155) | 0.17 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| VT | 37% (58/155) | 47% (72/155) | 12% (18/155) | 0.11 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Significant bradycardia | 6.5% (10/155) | 10% (16/155) | 2.6% (4/155) | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.010 | 0.017 |

| AV block grade ≥ 2 | 2.6% (4/155) | 5.8% (9/155) | 0.6% (1/155) | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.034 | 0.021 |

| Asystole | 4.5% (7/155) | 5.2% (8/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.26 |

| 24–72 h | |||||||

| LTVA or death | 5.2% (8/155) | 3.9% (6/155) | 1.9% (3/155) | 0.59 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.29 |

| VT, VF, or death | 28% (43/155) | 31% (48/155) | 9.7% (15/155) | 0.53 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

- AV, atrioventricular; LTVA, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

- * Anterior STEMI vs. non-anterior STEMI.

- ** Takotsubo vs. anterior STEMI.

- *** Takotsubo vs. non-anterior STEMI.

After multivariable adjustment, TS remained associated with a lower risk of the composite of LTVA or death driven by a lower risk for LTVA compared with STEMI (Table 3). The adjusted risk for VT/VF was also lower in TS compared with STEMI, and remained lower in TS vs. anterior and non-anterior STEMI between 24 and 72 h.

| Outcome | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| TS vs. anterior STEMI | TS vs. non-anterior STEMI | |

| Within 72 h | ||

| LTVA or death | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.58) | 0.29 (0.09 to 0.93) |

| VT, VF, or death | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.38) | 0.16 (0.09 to 0.28) |

| VT or VF | 0.20 (0.12 to 0.36) | 0.14 (0.08 to 0.26) |

| 24–72 h | ||

| LTVA or death | 0.50 (0.11 to 2.18) | 0.51 (0.11 to 2.28) |

| VT, VF, or death | 0.27 (0.14 to 0.52) | 0.21 (0.11 to 0.40) |

| VT or VF | 0.24 (0.11 to 0.49) | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.36) |

- LTVA, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia (sustained VT or VF); STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; TS, Takotsubo syndrome; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

There was no significant interaction between presentation with AHF or CS and Takotsubo vs. STEMI for the risk of LTVA or VT/VF (pinteraction = 0.49 and 0.68). There was also no significant interaction in regard to the risk of LTVA or VT/VF between TS vs. STEMI and prolonged QTc (pinteraction = 0.82 and 0.25) or absolute QTc (pinteraction = 0.68 and 0.13). Predictors of the composites of LTVA or death among patients with TS, anterior STEMI, and non-anterior STEMI are presented in Table 4.

| Predictors | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Takotsubo | Anterior STEMI | Non-anterior STEMI | |

| Predictors of LTVA or death | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.0 (0.94 to 1.1) | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.02) | 1.0 (0.96 to 1.04) |

| Sex | N/Aa | 0.94 (0.20 to 4.5) | 0.56 (0.11 to 2.8) |

| Diabetes | N/Aa | 0.41 (0.051 to 3.3) | 2.0 (0.49 to 7.8) |

| Current smoking | 1.4 (0.12 to 16) | 1.9 (0.65 to 5.4) | 0.75 (0.2 to 2.7) |

| Previous MI | N/Aa | 0.47 (0.058 to 3.8) | 1.9 (0.38 to 9.6) |

| Previous PCI | N/Aa | N/Aa | 2.8 (0.52 to 14) |

| Presentation with AHF | 7.8 (0.79 to 77) | 3.15 (1.2 to 8.1)* | 6.5 (2.1 to 20)* |

| Beta blocker at admission | N/Aa | 1.4 (0.50 to 3.9) | 2.9 (0.96 to 9.0) |

| Heart rate at admission (per 10 bpm) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) | 1.0 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) |

| QTc at admission (per 10 ms) | 1.0 (0.98 to 1.03) | 1.0 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) * |

| Long QTc at admission | 1.6 (0.17 to 16) | 0.64 (0.25 to 1.7) | 4.6 (1.4 to 14)* |

| T-wave inversion at admission | 0.42 (0.042 to 4.1) | 0.69 (0.27 to 1.7) | 0.65 (0.17 to 2.5) |

- AHF, acute heart failure; LTVA, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia (sustained VT or VF); MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; TS, Takotsubo syndrome; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

- a Zero events in one of the categories.

- * Statistically significant at P < 0.05.

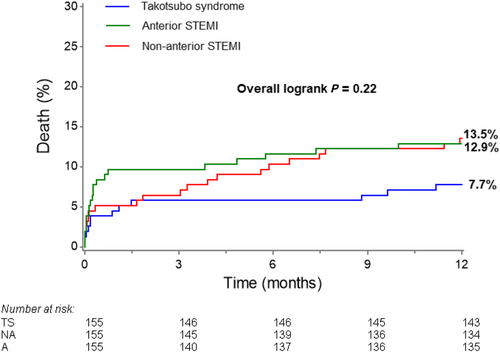

The risk of dying within 1 year was 7.7% for patients with TS vs. 13.2% for patients with STEMI (P = 0.08), with similar rates among patients with anterior and non-anterior STEMI (Figure 2). Among patients with STEMI, the 1 year mortality was 19% for those with sustained VT or vs. 13% for those without sustained VT or VF (P = 0.37). The composite of any VT or VF was not associated with increased risk of dying among patients with TS (P = 0.84), anterior STEMI (P = 0.10) or non-anterior STEMI (P = 0.76).

Discussion

The major finding in the present analysis was that the risk of LTVA within the first 72 h in-hospital was considerably lower for patients with TS than for patients with STEMI, even after perfectly matching patients with TS and STEMI by sex, and despite similar or greater incidence of AHF and similar incidence of CS in TS.

An important strength of our study compared with previous studies is the precise matching of patients with TS vs. STEMI by sex, resulting in a study cohort predominantly made up of women. Because there are important differences between women and men in the pathophysiology of STEMI, and the propensity for arrhythmias or poor outcome after STEMI,18, 21-27 it is difficult to know whether differences observed in previous studies between predominantly male patients with STEMI and predominantly female patients with TS are related to sex disease entity (TS vs. STEMI). Simply adjusting for sex in multivariable statistical models may not be enough if the sex disparity in the comparator groups is as large as it tends to be between STEMI and TS.20, 28, 29 Nevertheless, the main observation in our study that ventricular arrhythmias are less common after TS than STEMI is consistent with previous studies.28, 30 These arrhythmias included sustained VT and VF and were not restricted to short bursts of non-sustained VT. Our results confirm that, even though the extent of LV akinesia is at least as extensive in TS as in STEMI, cardiac electrophysiology appears to remain more stable in TS than STEMI.

The incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with Takotsubo in our study is consistent with, albeit slightly higher than, that reported in other cohorts of patients with Takotsubo.6, 12, 31-41 The higher rate of ventricular arrhythmias observed in our study was driven by a higher incidence of non-sustained VT and may be explained be the fact that the availability of continuous telemetry data for all patients in our study allowed us to capture and record most, if not all, ventricular arrhythmias. In contrast, only one LTVA occurred in patients with Takotsubo in our study. The incidence of LTVA has been reported to be slightly higher in other Takotsubo cohorts but was low also in other studies.12, 32, 35, 36, 40, 41

The incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with STEMI in our study is also largely consistent with previous studies, although we noted a relatively low incidence of sustained VT and VF compared with other studies.2 The lower incidence of sustained VT and VF in our study compared with others may be related to the fact that most patients in our study were women, because women have been shown to have a lower incidence of ventricular arrhythmias than men after STEMI.18 Even if the incidence of sustained VT or VF among patients with STEMI in our study was relatively low compared with other studies, it was substantially higher than for patients with TS.

Statistically significant predictors of LTVA or death among patients with STEMI included AHF in patients (both anterior or non-anterior STEMI) and long QTc in patients with non-anterior STEMI. There were no statistically significant predictors of LTVA or death among patients with TS. The fact that AHF was a significant predictor of LTVA or death in patients with STEMI and not in patients with TS may also be in part related to the fact that there were few such events among patients with TS, resulting in low statistical power to detect an association. It should also be noted that there was no statistical interaction between TS vs. STEMI and AHF for the risk of LTVA or death, supporting the notion that the study was not sufficiently powered to examine this relationship. That said, an alternative explanation for a stronger association between the risk of LTVA or death and AHF in STEMI vs. TS may be the stronger association between AHF and the degree of myocardial necrosis and electrical instability in STEMI vs. TS.2, 11, 19, 28

Acquired long QT-syndrome in the setting of STEMI or TS has been associated with increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias.10 In our cohort, long QTc at admission was significantly associated with increased risk of LTVA or death only among patients with non-anterior STEMI. The lack of association between QTc and LTVA or death in patients with anterior STEMI or TS may be partly explained by the relatively small sample size in our study. However, the lack of an association between QTc on the admission ECG and the risk of LTVA or death in TS is consistent with the observation that ventricular arrhythmias and QT-prolongation in TS are most common in the subacute phase.11, 37, 42 It is possible that admission QTc is not representative for the acquired QTc-prolongation seen later in the clinical course of TS.

The lack of an association between QTc and LTVA or death in anterior STEMI is also consistent with previous data, because early and transient prolongation of QTc in anterior STEMI have been associated with stunned viable myocardium with increased potential for recovering cardiac function, smaller infarct size, and higher LVEF. This transient QTc-prolongation has been described to differ from the persistent QTc-prolongation associated with an increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia and poor outcome.43, 44 To the best of our knowledge, the phenomenon with transient long QTc as a marker for stunning has not been demonstrated in non-anterior STEMI specifically. Additional studies, ideally with serial assessment of ECGs, are needed to better understand the dynamic nature of QTc prolongation in anterior vs. non-anterior STEMI.

Our study was not powered to detect differences in mortality between patients with TS and STEMI, and the nominally lower crude 1 year mortality among patients with TS vs. STEMI was not statistically significant. Larger studies are necessary to shed further light on the relative mortality risk in TS vs. STEMI.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the study is retrospective, which precluded us from collecting information that was not already available in the patient charts. However, we reviewed all patient charts, echocardiograms, electrocardiograms, and telemetry reports to validate the diagnoses of TS and STEMI and to record all arrhythmias. Second, the number of patients with TS was relatively small and most were women. Our results are therefore most applicable to women with TS and STEMI. However, the validation of all diagnoses and the sex-based and age-based matching of all TS patients 1:1:1 to patients with anterior STEMI and non-anterior STEMI allowed us to compare the TS cohort with meaningful comparator groups. Third, although complete 1 year follow-up was available for all patients, we did not have information on the specific cause of death for those that died.

Conclusions

In a predominantly female age-matched and sex-matched cohort of patients with TS, anterior STEMI, and non-anterior STEMI, the adjusted risk of in-hospital LTVA was considerably lower in TS compared with STEMI, despite similar or greater risk of AHF and similar risk of cardiogenic shock in TS.

Conflict of interest

None declared. Rickard Zeijlon, Jasmina Chamat, Israa Enabtawi, Sandeep Jha, Mohammed Munir Mohammed, Johan Wågerman, Vina Le, Aaron Shekka Espinosa, Erik Nyman, Elmir Omerovic, and Björn Redfors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (20180555) and the Swedish Society of Medical Research (181015).