Prevalence and prognostic value of autonomic neuropathy assessed by Sudoscan® in transthyretin wild-type cardiac amyloidosis

Abstract

Aims

The prevalence of autonomic neuropathy (AN) is high in patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis but remains unknown in transthyretin wild-type cardiac amyloidosis (ATTRwt-CA). This study aimed to determine the prevalence of AN in patients with ATTRwt-CA using Sudoscan®, a non-invasive method used to provide evidence of AN in clinical practice and based on measurement of electrochemical skin conductance at the hands and feet (fESC).

Methods and results

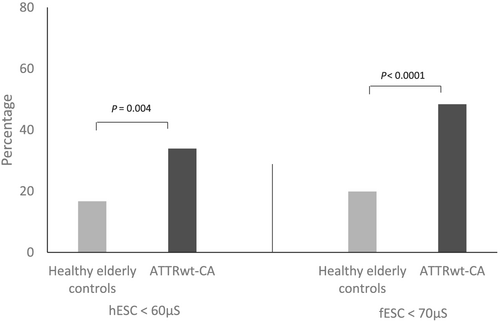

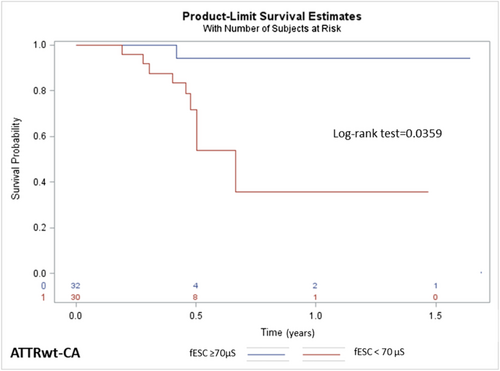

A series of 62 non-diabetic patients with ATTRwt-CA was prospectively included over 2 years and compared with healthy elderly subjects, matched by age, gender, and body mass index. The presence of AN was defined as electrochemical skin conductance at the hands <60 μS and/or fESC <70 μS, and conductances were analysed according to clinical, biological, and echocardiographic data. Mean fESC was significantly lower in patients with ATTRwt-CA compared with elderly controls: 68.3 (64.1–72.5) vs. 76.9 (75.6–78.1) μS (P < 0.0001), respectively. Prevalence of fESC <70 μS was higher in ATTRwt-CA patients than in controls: 48.4% vs. 19.9%, P < 0.05. Univariate analysis showed that fESC, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, creatinine plasma levels, and echocardiographic global longitudinal strain were associated with decompensated cardiac failure and death. Multivariate analysis revealed that fESC was an independent prognostic factor, and Kaplan–Meier estimator evidenced a greater occurrence of cardiac decompensation and death in patients with fESC <70 μS, P = 0.046.

Conclusions

Reduced fESC was observed in almost 50% of patients with ATTRwt-CA and was associated with a worse prognosis. Sudoscan® could easily be used to screen ATTRwt-CA patients for the presence of AN and identify patients at higher risk for a poor outcome.

Introduction

Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) is a severe, progressive, and fatal systemic disease, characterized by an accumulation of insoluble fibril proteins in the extracellular matrix of various organs including the heart and peripheral nerves.1, 2 There are two main types of ATTR: a hereditary or mutated variant (ATTRv) and a wild-type (ATTRwt-CA), also named senile systemic amyloidosis, age-related amyloidosis, or senile cardiac amyloidosis. ATTRwt-CA predominantly affects the heart with a very strong predominance for patients over 60 years of age.2, 3 The ATTRwt-CA clinical phenotype includes concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, preserved left ventricular ejection fraction,2-4 and normal or low QRS voltages on electrocardiogram.3, 4 Patients affected by ATTRwt-CA can suffer from heart failure, arrhythmias, and other common, cardiac manifestations.3, 4 Although ATTRwt-CA mainly involves the heart, focal neurological manifestations have been reported, including carpal tunnel syndrome or lumbar spinal canal stenosis.3, 4 However, the occurrence of more diffuse involvement of peripheral nerves in the context of ATTRwt-CA is not known.

Among the different types of nerve fibres, amyloid disorders preferentially affect fibres of small diameter, that is, thinly myelinated Aδ fibres and unmyelinated C fibres, which convey either thermalgesic sensory or autonomic information. This leads to a diffuse, symmetrical, length-dependent small fibre neuropathy, involving in particular the unmyelinated C fibres of the autonomic nervous system. There are several methods to assess autonomic fibres, including cardiovascular and sudomotor tests.5 Most of these methods are time-consuming and require highly specialized and expensive equipment. Conversely, the Sudoscan® device allows rapid and objective evaluation of sweat gland innervation at the extremities by measuring electrochemical skin conductance (ESC)6, 7 according to a chronoamperometric method. Briefly, a direct current of low voltage (<4 V) is incrementally applied to the skin through a pair of electrodes; the skin then generates a current whose intensity (around 0.2 mA) is proportional to the density of chloride ions drawn from the sweat glands (reverse iontophoresis). The ratio between the current generated by the reaction of the chloride ions with the electrodes and the voltage of the direct current delivered by the electrodes (Ohm's law) is defined as the ESC and measured in microSiemens (μS). The ESC represents the ease with which the electric current passes through an axonal reflex involving autonomic C fibres and depends on the production of chloride ions by sweat glands. Therefore, a reduced ESC principally reflects a reduced innervation of the sweat glands by unmyelinated C fibres. For this reason, ESC assessment is now considered a useful method for the diagnosis of autonomic neuropathy (AN) in clinical practice, as evidenced by its use in AN of various origins, including diabetes6-8 and ATTRv.9-11 In particular, a correlation has been found between ESC measures and the severity of ATTRv,10 and it has been suggested that a decrease in ESC could be an early marker of the disease.12 Little is known about the occurrence and clinical consequences of AN in ATTRwt-CA. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the presence of AN in patients with ATTRwt-CA through ESC measurement.

Methods

Study populations

Patients with ATTRwt-CA were compared with a control group of healthy elderly subjects. Between 2018 and 2019, we screened 74 patients with confirmed ATTRwt-CA, referred for hospitalization or consultation to the French referral centre for Cardiac Amyloidosis at the Henri Mondor University Hospital, Créteil, France. Among these 74 ATTRwt-CA patients, 12 patients with diabetes (treated with oral drugs or insulin) were excluded from the study to avoid potential bias due to the presence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The remaining 62 patients were included in the study. Data were recorded electronically according to the French CNIL (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés), and written informed consent for participation in the Amyloidosis Network registry was obtained from each patient. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (authorization number 1431858).

Healthy elderly subjects serving as controls were issued from the PROgnostic indicator OF cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (PROOF) study, which was a prospective longitudinal cohort study recruiting inhabitants of the city of Saint Etienne, France, who were over 65 years of age. Subjects with prior cardiac events such as myocardial infarction and congestive heart disease, diabetes, dependent people or people living in institutions, were excluded from this study. All subjects signed an informed consent form before being included in the PROOF study, which was approved by the local ethics committee (CCPRB Rhône-Alpes Loire).

Diagnosis of wild-type cardiac amyloidosis

Transthyretin amyloidosis diagnosis was based on TTR typical Congo red staining, and positive staining with TTR antibodies on endomyocardial or extra-myocardiac biopsy,13 and/or on bisphosphonate scintigraphy. Genetic sequencing of ATTR was performed to differentiate ATTRwt-CA from ATTRv. A diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis was considered in patients with amyloidosis when there was an increase in wall thickness (>12 mm) measured at echocardiography in the absence of another known cause of cardiac hypertrophy and increased plasma levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) above 332 ng/L (in the absence of renal failure or atrial fibrillation). The severity of cardiac amyloidosis was assessed using two biological markers, that is, plasma levels of high-sensitivity troponin T and NT-proBNP.

Data collection

Data collected for ATTRwt-CA patients included demographic information (age and gender), body mass index (BMI), cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes, dyslipidaemia, or high blood pressure), average heart rate, average systolic and diastolic blood pressures, New York Heart Association functional classification of heart failure, and presence of cardiac arrhythmia, pacemaker, or implantable cardioverter–defibrillator. All patients also had an evaluation of cardiac and renal biomarkers (plasma levels of high-sensitivity troponin T, NT-proBNP, and creatinine), an electrocardiogram, a transthoracic echocardiography (with measurement of left ventricular ejection fraction, interventricular septal thickness, and global longitudinal strain), and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Extra-cardiac amyloid symptoms were sought for all patients by a senior specialist in amyloidosis. Neurological involvement was also investigated, including the presence of symptoms, signs, or medical history of diffuse neuropathy (e.g. paresthesia and urinary bladder disturbances), carpal tunnel syndrome, nerve root lesion (spinal stenosis), severe hypoacusis or deafness, or dysautonomia (e.g. orthostatic hypotension or gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting and diarrhoea). Finally, the presence of Dupuytren's contracture was recorded.

For the healthy elderly controls, only age, gender, and BMI were recorded. As mentioned earlier, subjects with history of cardiac events or diabetes were excluded.

Electrochemical skin conductance

In all ATTRwt-CA patients and healthy elderly controls, ESC was measured at the hands (hESC) and feet (fESC) using Sudoscan® (Impeto Medical, Paris, France). During a 3 min scan, subjects were asked to stand and place the palms and soles on large stainless-steel electrodes. Then hESC and fESC were recorded bilaterally and compared with normal values published in the literature, with a lower limit of normal of 60 μS for hESC and 70 μS for fESC.14

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using SAS software (Statistical Analysis System 9.4 Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Quantitative continuous variables were expressed as mean (95% confidential interval) and qualitative categorical variables as percentages. Comparisons were made using Student's t-test for quantitative values and χ2 test for qualitative values. Pearson's correlation was used to study right/left correlations of ESC values. A survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test. In univariate and multivariate analyses, the Cox proportional risk regression model (backward selection) was used to evaluate the independent risk factors for cardiac decompensation and for death. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of the populations

In our cohort of 62 patients with ATTRwt-CA (Table 1), there were mainly men (n = 58, 93.5%), with a mean age of 78.6 years (76.7–80.6) and a mean BMI of 25.3 kg/m2 (24.4–26.2). In this population, 30.7% of patients had symptoms compatible with peripheral neuropathy (mostly pain, numbness, and weakness), 80.3% had symptoms or a history of carpal tunnel syndrome (unilateral or bilateral), 18.3% had symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis, 22.6% had dysautonomic symptoms (mainly orthostatic hypotension), and 28.2% had Dupuytren's contracture. A cohort of 186 healthy elderly controls was matched by gender (94.2% of men), age [mean 74.8 years (74.6–75.0)], and BMI [mean 25.0 kg/m2 (24.2–26.8)].

| ATTRwt-CA | |

|---|---|

| N | 62 |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Age, years | 78.6 (76.7; 80.6) |

| Male, n (%) | 58 (93.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 (24.4; 26.2) |

| CV characteristics | |

| NYHA class III–IV vs. I–II, n (%) | 20 (32.3) |

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 77.1 (73.9; 80.3) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 130.6 (126.5; 134.7) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75.7 (73.3; 78.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 8 (14.0) |

| Pacemaker, n (%) | 29 (46.8) |

| ICD, n (%) | 11 (17.7) |

| CV risk factors | |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 28 (45.2) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 38 (61.3) |

| History and reported symptoms | |

| Carpal tunnel surgery or symptoms, n (%) | 49 (80.3) |

| Bilateral carpal tunnel | 38 (61.3) |

| Left carpal tunnel alone | 4 (6.5) |

| Right carpal tunnel alone | 4 (6.5) |

| Carpal tunnel surgery (alone, bilateral, or right or left), n (%) | 35 (57.4) |

| Lumbar spinal stenosis surgery, n (%) | 11 (18.3) |

| Dupuytren's syndrome, n (%) | 11 (28.2) |

| Deafness, n (%) | 41 (66.1) |

| Symptomatic neuropathy, n (%) | 19 (30.7) |

| Symptomatic dysautonomia (orthostatic hypotension), n (%) | 14 (22.6) |

| Symptomatic gastrointestinal dysautonomia, n (%) | 16 (25.8) |

| Biological variables | |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 4528 (3463; 5594) |

| NT-proBNP and eGFR staginga, n (%) | |

| Stage 1 | 23 (37.1) |

| Stage 2 | 30 (48.4) |

| Stage 3 | 9 (14.5) |

| hs-TnT, ng/mL | 85.0 (55.6; 114.3) |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 13.5 (12.6; 14.5) |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 121.4 (109.7; 133.1) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 59.8 (54.2; 65.3) |

| Echocardiography characteristics | |

| LVEF, % | 46.8 (43.7; 50.0) |

| IVST, mm | 18.6 (17.7; 19.5) |

| GLS, % | 9.1 (8.2; 10.0) |

- ATTRwt-CA, transthyretin wild-type cardiac amyloidosis; BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLS, global longitudinal strain; hs-TnT, high-sensitivity troponin T; ICD, implantable cardioverter–defibrillator; IVST, interventricular septum thickness; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

- Values are mean (95% confidence interval) except for NT-proBNP and hs-TnT (median and interquartile range).

- a Following Gillmore, Damy, et al. EHJ 2017, 35 Stage 1 was defined as NT-proBNP ≤3000 ng/L and eGFR ≥45 mL/min, Stage 3 was defined as NT-proBNP >3000 ng/L and eGFR <45 mL/min, and the remainder were Stage 2.

Electrochemical skin conductance

The mean hESC and fESC were significantly lower in patients with ATTRwt-CA than in elderly controls (Table 2). In addition, the percentages of subjects with hESC <60 μS and/or fESC <70 μS were significantly higher in patients with ATTRwt-CA than in elderly controls: 33.9% vs. 16.7% for hESC and 48.4% vs. 19.9% for fESC, respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). In patients with ATTRwt-CA compared with healthy elderly controls, reduced hESC and fESC (<60 μS and <70 μS, respectively) were more frequently observed either concomitantly (24.2% vs. 8.1%, P < 0.0001) or independently (only reduced hESC: 9.7% vs. 8.6%, P < 0.0001; only reduced fESC: 24.2% vs. 11.8%, P < 0.0001). In the subgroup of controls or patients with hESC <60 μS or fESC <70 μS, mean values were also significantly lower in patients with ATTRwt-CA than in controls (Table 2).

| Variables | Elderly healthy control | ATTRwt-CA | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | ||||

| Mean fESC in all (μS) | 186 | 76.9 (75.6–78.1) | 62 | 68.3 (64.1–72.5) | <0.0001 |

| Mean hESC in all (μS) | 186 | 70.0 (68.5–71.5) | 62 | 61.5 (57.0–66.0) | 0.0006 |

| Mean fESC in <70 μS group (μS) | 37 | 64.3 (62.6–66.0) | 30 | 54.5 (49.9–59.1) | 0.0002 |

| Mean hESC in <60 μS group (μS) | 31 | 53.5 (51.3–55.7) | 17 | 40.4 (35.1–45.8) | <0.0001 |

- ATTRwt-CA, transthyretin wild-type cardiac amyloidosis.

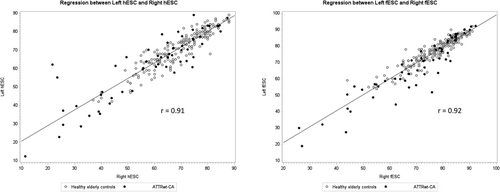

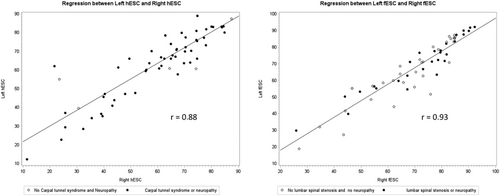

In both healthy elderly controls and patients with ATTRwt-CA, right and left ESC values were symmetrical and highly correlated (Figure 2). A similar correlation between right and left hESC or fESC values was observed regardless of the presence of carpal tunnel syndrome, symptomatic neuropathy (including paresthesia and urinary bladder disturbances), or lumbar spinal stenosis (Figure 3). No significant difference was observed in hESC in ATTRwt-CA patients whether symptoms or history of carpal tunnel syndrome was present (n = 54) or absent (n = 8) [mean (95% confidence interval): 61.0 μS (55.8–66.2) vs. 62.4 μS (51.3–73.4), P = 0.81].

Relationship between electrochemical skin conductance and functional cardiac status and prognosis

In the 62 patients with ATTRwt-CA, a survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier method showed a larger occurrence of cardiac decompensation and death in patients with fESC <70 μS (Figure 4). Univariate analysis indicated that the hESC, fESC, plasma NT-proBNP and creatinine levels, and echocardiographic global longitudinal strain were associated with cardiac decompensation and death (Table 3). In the multivariate Cox model analysis (Model 2), including demography, ESC, and biological markers, age, fESC, and NT-pro-BNP plasma level were identified as independent prognostic factors (Table 3). Patients with fESC <70 μS showed worse cardiac status with higher NT-pro-BNP levels than those with fESC ≥70 μS (P = 0.0204). The value of estimated glomerular filtration rate was also significantly lower in patients with fESC <70 μS (P = 0.0014), although age was similar compared with patients with fESC ≥70 μS (Table 4).

| Class | Variables | Univariate model | Multivariate Model 1 Demography + ESC | Multivariate Model 2 Model 1 + biology | Multivariate Model 3 Model 2 + echocardiography | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Demography | Age, years | 0.799 | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.301 | 0.95 (0.86–1.05) | 0.07 | 0.91 (0.83–1.01) | 0.108 | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) |

| Clinical history | NYHA, class | 0.979 | 0.98 (0.25–3.82) | 0.607 | 1.48 (0.34–6.50) | 0.276 | 2.61 (0.46–14.66) | ||

| ESC (Sudoscan) | fESC, μS | 0.006 | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 0.005 | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 0.046 | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.09 | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) |

| hESC, μS | 0.037 | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | |||||||

| Biology | NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 0.015 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.026 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 0.059 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | ||

| hs-TnT, ng/mL | 0.549 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | |||||||

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 0.023 | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | |||||||

| Echocardiography | GLS, % | 0.079 | 0.80 (0.61–1.03) | 0.377 | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) | ||||

- CI, confidence interval; ESC, electrochemical skin conductance; fESC, electrochemical skin conductance at the feet; GLS, global longitudinal strain; hESC, electrochemical skin conductance at the hands; HR, hazard ratio; hs-TnT, high-sensitivity troponin T; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

| ATTRwt-CA | ATTRwt-CA | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | fESC ≥70 μS | fESC <70 μS | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 78.3 (75.9; 80.8) | 78.9 (75.7; 82.3) | 0.7564 |

| NYHA class III–IV vs. I–II, n (%) | 10 (31.3) | 10 (33.3) | 0.5379 |

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 78.4 (73.6; 83.2) | 75.6 (71.2; 80.0) | 0.3813 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 133.4 (126.8; 139.9) | 127.7 (122.8; 132.6) | 0.1627 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (16.0) | 0.1192 |

| Pacemaker, n (%) | 14 (43.8) | 15 (50.0) | 0.5470 |

| ICD, n (%) | 2 (6.3) | 9 (30.0) | 0.0298 |

| History and reported symptoms | |||

| Carpal tunnel surgery or symptoms, n (%) | 26 (81.3) | 23 (76.7) | 0.4559 |

| Lumbar spinal stenosis surgery, n (%) | 6 (19.4) | 5 (17.2) | 0.8981 |

| Symptomatic neuropathy, n (%) | 11 (34.4) | 8 (26.7) | 0.3323 |

| Biological variables | |||

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 3367.3 (2107.4; 4627.2) | 5813.8 (4100.0; 7527.5) | 0.0204 |

| NT-proBNP and eGFR staging**, n (%) | 0.0116 | ||

| Stage 1 | 16 (50) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Stage 2 | 15 (46.9) | 15 (50) | |

| Stage 3 | 1 (3.1) | 8 (26.7) | |

| hs-TnT, ng/mL | 61.8 (46.5; 77.14) | 109.0 (50.6; 167.5) | 0.1064 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 67.8 (60.3; 75.2) | 50.6 (43.3; 57.9) | 0.0014 |

| Echocardiography characteristics | |||

| LVEF, % | 49.0 (43.9; 54.1) | 44.4 (40.8;48.0) | 0.1361 |

| IVST, mm | 17.8 (16.6; 19.1) | 19.4 (18.2; 20.6) | 0.0669 |

| GLS, % | 9.6 (8.2; 11.1) | 8.6 (7.4; 9.7) | 0.2431 |

- ATTRwt-CA, transthyretin wild-type cardiac amyloidosis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; fESC, electrochemical skin conductance at the feet; GLS, global longitudinal strain; hs-TnT, high-sensitivity troponin T; ICD, implantable cardioverter–defibrillator; IVST, interventricular septum thickness; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to objectively assess the presence of AN in a cohort of patients with ATTRwt-CA. The main results of this study are as follows: (i) hESC and fESC values are significantly reduced in ATTRwt-CA patients compared with age-matched, sex-matched, and BMI-matched healthy elderly controls, with ATTRwt-CA patients also demonstrating a higher rate of abnormal hESC and fESC measures (<60 and <70 μS, respectively); and (ii) abnormally reduced fESC was associated with poorer functional cardiac status and prognosis (higher NT-pro-BNP plasma level and higher occurrence of cardiac decompensation or death).

Prevalence of autonomic neuropathy in transthyretin wild-type cardiac amyloidosis patients

According to hESC and fESC measurements, almost half of patients with ATTRwt-CA (48.4%) presented AN. There is no previous publication assessing the prevalence of AN in ATTRwt-CA, as evaluated using an objective and quantitative test. A few studies reported neurologic symptoms in cohorts of ATTRwt-CA patients.16, 17 In a cohort of 166 ATTRwt-CA patients with a mean age of 76 years, Maurer et al.18 first showed a prevalence of 12% of neuropathic pain, 22% of numbness, and 13% of tingling, symptoms that suggest the presence of sensory neuropathy. These percentages were lower compared with patients with ATTRv and V122I mutation.19 In the first Japanese nationwide cohort including 51 patients with a mean age of 72 years, Sekijima et al.20 reported sensory disturbance at the upper and/or lower limbs in 14%, weakness in 12%, and orthostatic hypotension in 6%. In our cohort of 62 patients with a mean age of 79 years, 31% of patients reported symptoms or signs of neuropathy (mostly pain, numbness, and weakness) and 23% symptoms or signs of dysautonomia (mainly orthostatic hypotension). Thus, the presence of sensory neuropathy is frequent in patients with ATTRwt-CA. Our study has the advantage of comparing ESC measures in patients with ATTRwt-CA with those of an elderly control population matched by age, gender, and BMI. It confirms that the prevalence of distal neuropathy, specifically involving autonomic nerve fibres, is significantly increased in the context of ATTRwt-CA. Indeed, reduced ESC values are a reliable marker of AN, although not associated with the presence of sensory symptoms in our cohort. The difference in prevalence of symptoms and abnormal ESC could be explained by the fact that ESC measurement is objective, contrary to symptoms reported by the patient. Moreover, the results observed in this study in ATTRwt-CA patients are comparable with results previously observed in patients with ATTRv. In a study of 21 patients with ATTRv, Zouari et al.21 showed that 14% of asymptomatic patients, 86% of patients with moderate neuropathy, and 100% of patients with advanced neuropathy had altered fESC (using 67 μS as lower limit of normal). In a series of 54 patients with either ATTRv-associated polyneuropathy or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, Fortanier et al.12 showed that 90% of patients with ATTRv had altered fESC, with an optimal threshold of fESC <64 μS to differentiate ATTRv from chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Finally, Montcuquet et al.34 reported that in a series of 49 patients with Amyloidosis light-chain (AL) amyloidosis, 74% of patients had fESC <70 μS, while only 29% had symptoms or signs of neuropathy, and 18% had clinical dysautonomia (orthostatic hypotension). Thus, ESC measurement, particularly at the feet, can be useful to highlight a distal AN in the context of amyloidosis, whatever its type, because small autonomic nerve fibres are involved early by the amyloidotic neuropathic process. However, it must be underlined that large fibre neuropathies are the most commonly observed neuropathies in amyloidosis and particularly in hereditary ATTR.9, 10

Functional correlates and prognostic value of autonomic neuropathy in the context of cardiac amyloidosis

In the course of ATTRv, up to 75% of patients develop symptoms of AN, affecting the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems. Amyloid AN can be very disabling with a high morbidity and mortality rate and an increased risk of sudden death.23-25 The assessment of sudomotor dysfunction using ESC measurement could help in the follow-up of cardiac AN as evidenced in previous studies.26-28 Our study revealed that ESC measurement, a rapid and simple test, may be of important clinical value in the context of cardiac amyloidosis by predicting a functional deterioration (cardiac decompensation) when fESC decreases. The association of AN and adverse cardiac events underlines the need to not neglect autonomic evaluation in cardiac amyloidosis, although it is usually underestimated in clinical cardiologic practice.

Early dysautonomia is a red flag in the diagnosis and therapeutic management of familial amyloid polyneuropathy associated with ATTRv29, and Sudoscan® is a first-line diagnostic test in this clinical condition. Our results suggest that the use and value of ESC measurement should be extended to ATTRwt-CA as well. In addition, ESC measurement can serve to follow the course of distal AN and its treatment, as previously shown in neuropathy associated with ATTRv,10, 30 chemotherapy,26, 27 or bariatric surgery.28 The present study is the first to demonstrate an association between fESC reduction and a poor functional prognosis (cardiac decompensation and death).

The diagnosis of autonomic neuropathy in clinical practice

The diagnosis of AN is usually based on different types of tests, such as skin biopsy and neurophysiological methods (e.g. Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test). The diagnostic sensitivity of ESC has been shown as better than Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test34, 35; in addition, this latter technique is time-consuming and requires very specialized skills. Conversely, ESC assessment is easy and very rapid to perform, possibly during the time of a cardiology consultation. ESC measurement is useful to complement clinical questionnaires such as the Composite Autonomic Symptom Score (COMPASS-31). Indeed, D'Amato et al.18 showed that the sensitivity of COMPASS-31 to detect AN increased from 59% to 85% when combined with fESC. In addition, ESC measures were found to correlate with the intraepidermal density of small nerve fibres on skin biopsy.26, 30, 32, 33 Thus, ESC assessment in ATTRwt-CA patients should improve the management of these patients to prevent the deleterious impact of dysautonomia on cardiomyopathic morbidity and mortality.18

The strengths of the study are as follows: (i) this is the first study on a relatively large population of patients with ATTRwt-CA to objectively assess AN, (ii) there is a 1 year follow-up with cardiac assessment for prognostic value, and (iii) the method used to assess AN is feasible in daily cardiology practice.

The limitations of the study are as follows: (i) ESC assessment was the only neurological test for dysautonomia used in this study along. It must be underscored that the performance of the method for AN assessment has been previously explored in a large number of studies compared with reference methods and was not the aim of this study, (ii) patients did not have an examination by neurologist; however, this was not the objective of the study, which was to assess the prevalence of AN by Sudoscan®, and (iii) patients did not undergo measurement of heart rate variability measurement, a validated marker of cardiac autonomic involvement.

Conclusions

Despite not including structured questionnaires for the assessment of dysautonomia (such as COMPASS-31) or peripheral neuropathy, this study has the merit of being the first to show that AN occurs in a large proportion of patients with ATTRwt-CA on the basis of ESC assessment, a reliable and validated test. Moreover, in this relatively large population of ATTRwt-CA patients, fESC reduction was associated with poor cardiac prognosis, highlighting the functional interest of this measure in daily cardiology practice. Sudoscan testing could be completed by the cardiologists and would allow patients with ATTRwt-CA and poor ESC to be triaged for consultation with a neurologist for further investigation, thus optimizing the management and monitoring of these patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Pr Violaine Plante Bordeneuve for his valuable advice and critical comments of the manuscript. The authors thank Impeto Medical, France, for providing the Sudoscan device as a loan for the study, A. Moutairou for help in statistical analysis, and J.H. Calvet for critical comments of the manuscript. The authors state that their study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, that the locally appointed ethics committee has approved the research protocol, and that informed consent has been obtained from the subjects (or their legally authorized representative).

Conflict of interest

M.K., M.B., S.S., C.C., A.Z., A.G., S.F., F.C.P., L.H., and J.P.L. have no conflict of interest to declare for this study. T.D. has received research grant and honorarium from Pfizer, Akcea, and Novartis and honorarium from Alnylam and Prothena. F.R. has no conflict of interest to declare for this study. The PROOF study was supported by two national PHRC (1998 and 2001; DGOS, URCIP CHU Saint Etienne).