Deliberating Justice in Citizen Jury Processes—Lessons for Just Transitions Governance

Funding: This work was supported by Research Council of Finland (341398) and Strategic Research Council established within the Research Council of Finland (358410).

ABSTRACT

Citizen juries are suggested as an effective tool for promoting just transition to low-carbon societies. However, citizen juries are influenced by participation rules, accepted discourses, and participants' perceptions about the need for climate policies. Therefore, it is crucial to better understand how citizens comprehend and deliberate justice in sustainability transition contexts. We analyzed two citizen juries conducted in Finland. One jury focused on the low-carbon transition in the transport sector, and the other on forest governance. We identified citizens' justice claims regarding the key aspects of justice (distributive, procedural, recognition, and restorative justice), supplemented by global, intergenerational, and ecological justice considerations. We analyzed how these claims developed during the deliberation. The transport jury emphasized distributive and recognition justice and increased awareness of diverse capacities and vulnerabilities related to the mobility transition. This jury also reinforced the participants' expectations regarding the legitimacy of certain nonsustainable lifestyles, such as private motoring. The forest jury emphasized procedural justice and forests as an intergenerational common good, but they also recognized forest owners' rights and legitimate claims for forest income. The juries demonstrate that citizen deliberation helps address justice concerns by revealing jurors' expectations regarding lifestyles and livelihood sources and proposing practical solutions. Our results suggest that citizen juries can enhance the formation of more informed and consistent, and thus legitimate, expectations.

1 Introduction

Sustainability transitions are urgently needed to combat climate change and biodiversity loss. At the same time, the costs and benefits of these transitions can be distributed unfairly, leading to unemployment, diminished economic security, limited opportunities for mobility, or other negative consequences (McCauley and Heffron 2018; Haas 2022). Moreover, transitions involving, for instance, wind and solar farms or mineral extraction for battery production can introduce new environmental challenges with associated social impacts (Heffron 2020; Mueller and Brooks 2020). Even conscious attempts to promote just energy transitions have, in some cases, exacerbated existing inequalities by focusing narrowly on specific groups, like coal workers, without considering the broader welfare of affected communities and their intersecting vulnerabilities (Weller 2019; Gürtler and Herberg 2021).

To better address justice in transitions governance, scholars have begun to explore the role of citizens in knowledge production and governance processes (Huttunen, Ojanen, et al. 2022; Daw et al. 2022). It is argued that improving participation opportunities can foster the fairness of sustainability transitions and their outcomes (Pickering et al. 2022; Ross et al. 2021; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts 2021). This perspective considers citizens as potential agents of regime change, capable of challenging vested interests and offering deeper insights on the potential impacts of transition policies on people's well-being and daily lives (Ross et al. 2021; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts 2021). However, citizens can also play a role in maintaining the status quo, and their perspectives may conflict with ambitious climate policies (Ciplet and Harrison 2020; Bowden et al. 2021; Huttunen et al. 2024; Pickering et al. 2022). Consequently, further exploration is required to comprehend how different understandings of justice are constructed in public deliberation. New empirical research is needed on how citizens themselves understand justice in sustainability transitions (Huttunen, Turunen, and Kaljonen 2022) and how these perspectives are negotiated within deliberative processes.

In this article, we focus on a specific deliberative design, the design of a citizen jury (CJ), and scrutinize how it enables citizens to address the complexities of low-carbon transitions and identify just solutions. Thus, we study how justice is “done” in the deliberative processes. CJs represent a form of a deliberative mini-public (DMP), defined as participatory spaces that bring together a representative cross-section of ordinary citizens to discuss and debate pressing decision-making questions, to hear experts, and to provide informed policy recommendations (Smith and Wales 2000; Grönlund et al. 2020). DMPs have emerged as a promising means for achieving agreement on justice claims and ensuring the fairness and acceptability of climate policies (Ross et al. 2021; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts 2021). DMPs are especially seen as capable of addressing the trade-offs inherent in sustainability transitions by tapping into the practical and moral intelligence of citizens in their everyday lives (Daw et al. 2022).

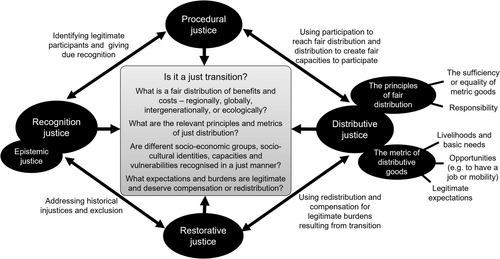

Regarding the conception of justice, we adopt a dimensional perspective encompassing the distributive, procedural, recognition, and restorative tenets (Schlosberg 2007; McCauley and Heffron 2018; Williams and Doyon 2019). These are supplemented by global, intergenerational, and ecological considerations. We apply the aspects of justice to two CJs and explore which aspects gain prominence and how the jurors' perceptions are affected by their expectations regarding legitimate lifestyles and livelihood sources in the future. The analysis provides an understanding of how justice is “done” in the deliberative processes. Thus, we are not focusing on the realization of objective justice but on how the aspects of justice are used in deliberation. The first CJ focused on reducing automobile carbon emissions in the Uusimaa region of Southern Finland and the other on forest management in Lapland, Northern Finland. In the densely populated Uusimaa, meeting the regional goals to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030 requires drastic measures to cut down automobile emissions. Conversely, in sparsely populated Northern Finland, a critical question is balancing timber production with the need to retain carbon sinks, maintain biodiversity, and sustain opportunities for the recreational use of forests. These two regional cases provide an understanding of the diverse transition challenges encompassing both urban and rural populations and various dimensions of justice.

2 Deliberating Just Transitions

2.1 A Just Transition

A just transition is commonly approached through distributive, recognition, and procedural justice with the addition of a restorative dimension (Schlosberg 2007; McCauley and Heffron 2018; Williams and Doyon 2019). Distributive justice refers to the equitable allocation of benefits and burdens arising from transitions. In the transport context, the pressing distributive concerns revolve around the accessibility and affordability of emerging transportation modes and services from the users' perspective (Mullen and Marsden 2016). Regarding the utilization of forest resources, equitable access to the multiple benefits of forests has been a recurring issue (see, e.g., Satyal et al. 2020; Martinez et al. 2023).

Accounts of distribution in climate transitions typically start with delineating the principles guiding the equitable distribution of transition impacts or responsibility. The principles of the fair distribution of impacts usually emphazise that people should have equal or sufficient opportunities to central goods, such as livelihoods and other resources for well-being. Other distributive principles focus on assigning responsibility for the environmental burdens. The “polluter pays” principle assigns responsibility to those who have caused the burdens, while “beneficiary pays”assigns it to those who have benefitted from causing the burdens, and “ability to pay” assigns it to those who have the capacity to deal with the burdens (Caney 2010; Kortetmäki and Huttunen 2022). In the transport transition, distribution concerns, for instance, car owners' responsibility for emissions. In forestry, the fair allocation of responsibility especially relates to the asymmetry of benefits and burdens: those who are responsible for the activities in the forests and are benefitting from them are often regionally and/or temporally distant from those who experience the burdens (see, e.g., Forsyth and Sikor 2013; Hoang et al. 2019; Satyal et al. 2020).

To measure legitimate distributive impacts, accounts of a just transition also need to specify the metric of the goods subject to the legitimate claims of just distribution. Since the metric should allow comparisons of people's distributive claims, objective metrics—such as basic needs, income, or job opportunities are—usually applied (see, e.g., Anderson 2010). However, in transitions, subjective expectations regarding the continuity of institutional rules and structures can become important. People's expectations about the possibilities of continuing their lifestyles based on, for example, private motoring or livelihoods obtained from fossil fuel production can strongly influence what they regard as just. Thus, expectations may play an important role when people contest transition policies—or when justice is formulated in deliberative processes, the focus of this study.

Despite their subjective nature, some expectations may still ground a legitimate metric for fair distribution. Since people's ability to formulate and pursue long-term life plans is often considered a central component of their good life (see, e.g., Rawls 1999), expectations about pursuing one's life plan can ground legitimate claims for compensation when transition disrupts an expectation based on good epistemic reasons (Meyer and Sanklecha 2014). This brings forward the restorative aspect of justice (McCauley and Heffron 2018). It implies that some of the distributional burdens resulting from transitions justify redistribution or compensation, particularly those that deprive people of their livelihoods and basic needs.

Recognition justice focuses on identifying and understanding sociocultural differences and the associated power disparities among different groups. The same policies can affect demographic groups differently, accentuating the accumulation of vulnerabilities (Fraser 2009) and the varying capacities of individuals to respond to transitions (Tribaldos and Kortetmäki 2022). For instance, ethnicity and gender disparities, as well as the challenges faced by the elderly or disabled, can influence access to transport (Karner et al. 2023). In forestry, the experiences, identities, and values of local communities have often been disregarded, resulting in insufficient recognition of multiple uses of forests beyond timber production (Poe et al. 2013; Morales 2021). Just recognition and inclusion also have an epistemic dimension: current understanding of the effects of transition policies may be insufficiently sensitive to people's lived experiences, historical injustices, and actual capabilities (Schwanen 2021). Therefore, failure in epistemic justice (Fricker 2007)—failure in recognizing the affected people's epistemic status—may undermine other aspects of justice.

Procedural justice concerns public decision-making principles, encompassing transparency, impartiality, accountability, and opportunities for public participation (Kivimaa et al. 2023). By creating spaces that facilitate the meaningful participation of marginalized and previously excluded groups, procedural justice directly relates to recognition and epistemic justice and provides means to enhance distributive justice. Distributional justice problems often stem from the marginalization of local communities in decision-making processes, be it forest management (see, e.g., Satyal et al. 2020; Martinez et al. 2023) or transport policy-making (Haas 2022).

In sustainability transitions, the notions of global, intergenerational, and ecological justices are especially relevant. These aspects draw attention to impacts across different nations and geographic locations, on future generations, nonhuman animals, and other environmental considerations arising from transitions (Tribaldos and Kortetmäki 2022; Celermajer et al. 2021). Concerning the above discussion on expectations, these notions of justice can be highly relevant in evaluating the potential legitimacy of expectations. As Meyer and Sanklecha (2014, 385–386) suggested, the legitimacy of people's expectations in climate transitions depends on whether they align, at least to some degree, with general claims of just global and intergenerational distribution: if one accepts that reducing global emissions is necessary to ensure that future generations can live decent lives and that the responsibilities for the reductions need to be distributed so that people today can live decently, then one's legitimate expectations should be within a range that is consistent with these claims. As a part of recognition justice, these expansions underscore the importance of addressing the historical and ongoing exclusion of certain groups, along with the disproportionate impacts experienced by them. This encompasses vulnerable and marginalized communities, future generations, and nonhumans (Williams and Doyon 2019, 148). In the forest sector, it is considered essential to address current social injustices to ensure the fair implementation of carbon policies (Satyal et al. 2020). In the transport sector, global justice concerns relate to electrified transportation and the associated demand for rare minerals (Prause and Dietz 2022). In both sectors, global justice issues related to climate change and the responsibilities for mitigating its effects are highly relevant (Schroeder and McDermott 2014).

Figure 1 illustrates the connections between different dimensions and core issues related to just transition that are used as the theoretical basis in the empirical analysis.

2.2 DMPs as Means to Facilitate Just Transitions

DMPs are forums for citizen participation, characterized by their combination of (stratified) random participant selection and structured deliberation. Examples of DMPs include CJs, citizens' assemblies, and deliberative polls. They all involve a representative subgroup of the population, provide participants with information, and engage them in an open and inclusive exchange of views concerning a given political issue. The process feeds into decision-making and public debate in the form of a statement, a report, or poll results (Curato et al. 2021; Smith and Setälä 2018). DMPs vary in their remit, defined by the DMP's convener, and also in duration and scale. CJs usually consist of 12–30 participants and convene over 2–5 days. Resembling the model of legal juries, CJs typically include expert or advocate testimonies and the scrutiny of evidence regarding the topic at hand. Jurors may also identify gaps in information and ask for further evidence. After weighing the evidence and deliberating, they collectively craft a statement in response to the task given to them (Smith and Setälä 2018; Crosby 1995). While our empirical focus is on CJs, here we discuss DMPs generally as the key design features (and challenges) relevant to our argument are shared across different formats of DMPs.

At a broad level, the mere organization of a DMP can be seen as enhancing procedural and recognition justice because it increases participation opportunities and enables the voicing of citizens' diverse concerns (Ross et al. 2021), though one could also argue that it risks crowding out other participation opportunities (Lafont 2015). Overall, it remains unclear if DMPs can promote more just outcomes—and if so, through which mechanisms they can do so—and how participants perceive justice in different contexts (Daw et al. 2022). According to Dryzek and Tanasoca (2021), the moral work required to apply the theoretical principles of justice in specific policy contexts is best conducted through democratic deliberation. They argue that deliberation is likely to promote justice because it facilitates the due consideration of competing interests and, by enhancing the epistemic competence of participating individuals, enables the identification of the best available solutions (Dryzek and Tanasoca 2021). Ideally, DMPs are valuable tools in advancing recognition and epistemic justice since DMPs aid affected communities in voicing their experiences and concerns (Ross et al. 2021). In DMPs, citizens learn from experts as well as learn the perspectives and values of other participants (Dryzek and Pickering 2019, 133). When DMPs are tasked with weighing various aspects of justice, they enable citizens to exercise formative agency (Dryzek and Tanasoca 2021), that is, to formulate the meaning of fairness within each policy context. In this way, DMPs are “doing” justice.

In the context of climate change, DMPs have increased participants' understanding of the issue, their readiness for action, and their ability to embrace a wider range of policy options (see, e.g., Niemeyer 2013; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts 2021). This suggests there is potential to foster distributive and recognition justice in relation to the burdens of climate change impacts on future generations and nonhuman others (Grönlund et al. 2020; Kulha et al. 2021; Willis et al. 2022). Furthermore, climate assemblies have recognized the needs of different communities and emphasized polluters' responsibility for their emissions (Scotland's Climate Assembly 2021). However, the ability of DMPs to foster intergenerational and global justice remains poorly evidenced (Daw et al. 2022).

Regarding procedural and recognition justice, the protected spaces created by DMPs can mitigate the influence of dominant groups in shaping political agendas (Willis et al. 2022; Daw et al. 2022). However, depending on their design, DMPs can also inadvertently perpetuate existing power imbalances (Pickering et al. 2022; Ross et al. 2021), for instance, by imposing a dominant definition of the common interest or emphasizing rationality in argumentation (Bond 2011). In addition, randomly selected jurors may not bring up the voices of disadvantaged groups; rather, deliberative forums need to be coupled with enclave deliberation for the disempowered (Karpowitz et al. 2009; Abdullah et al. 2016). Thus, the design and execution of deliberative processes strongly shape the outcomes (Chilvers and Longhurst 2016) and are instrumental in determining the DMP's capacity to address justice-related concerns.

The addressing of justice in DMPs faces similar design-related issues as those faced by DMPs in general. In particular, the framing of the task has been identified as central in affecting the deliberative quality, as well as the outcome, of DMPs. According to Bryant and Stone (2020), tight framing of the task can provide clear policy recommendations, but it may limit genuine citizen engagement by restricting citizens to preprepared options and a more consultative role, which can then contribute to problems such as perpetuating power imbalances. Thus, the framing of the task should be sufficiently wide-ranging to enable deliberative quality and a variety of potential recommendations (Niemeyer et al. 2024), but there is a trade-off between breadth and depth that also involves other factors, such as time, the resources provided, and the complexity of the issue (Wells et al. 2021; Elstub et al. 2021). In relation to promoting justice, DMPs with broad mandates have been identified as being promising for transcending conventional assumptions. They have the potential to generate novel insights into complex issues and stimulate innovative thinking, all while ensuring a more inclusive representation of marginalized perspectives (Daw et al. 2022). Thus, a broad task could enable deliberation on priorities and the general direction of climate policies (Wells et al. 2021) in a manner particularly useful regarding justice. However, citizens' formative agency in doing justice in policy contexts might benefit from a more specific task (Dryzek and Tanasoca 2021). Torney's (2021) analysis of climate assemblies in Ireland and France illustrates that, despite distinct tasks and designs, both assemblies clearly recommended the enhancement of climate policies. This suggests that the role of framing might be less important, but no previous studies empirically analyze justice dimensions in the deliberation process.

In our analysis, we approach the juries as forums for doing justice in the transport and forest policy contexts. We ask: (1) Which aspects of justice are relevant for the jurors? (2) What becomes of justice when it is deliberated in a CJ process and what role do expectations play in this?, and (3) How does the framing of the task of the jury influence the doing of justice in CJs?

3 Data and Methods

3.1 The Organized Juries

3.1.1 The Uusimaa Transport Jury

Uusimaa is Finland's most populous region with approximately 1.7 million residents spread across 26 municipalities of varying sizes. The regional authority, the Uusimaa Regional Council (URC), has prepared a Uusimaa Climate Roadmap (Uudenmaan liitto 2022) that sets the ambitious goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2030. Of particular concern is automobile transport, which accounts for 30% of climate emissions in Uusimaa. The URC was interested in citizens' perspectives on the roadmap's policy measures aimed at reducing carbon emissions from private cars. It was anticipated that some of these measures would be controversial as they may restrict private motoring and potentially increase transport costs. The task of the jury was framed relatively narrowly to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the proposed policy measures and craft recommendations for their implementation (not to choose among them). They were also invited to propose their own initiatives. The jury was convened together with the research team and the URC in the spring of 2022. The jury process is described in detail in (Saarikoski et al. 2023).

We recruited the jurors via a letter posted to 6000 randomly selected residents of Uusimaa. From the 440 volunteers interested in participating, we selected a stratified sample to ensure that the participants were representative of the broader Uusimaa population in terms of gender, age, place of residence, and education level. We also maintained a balance between car owners and non-owners.

The 32-member jury convened over two consecutive Saturdays and one weekend in April 2022. In addition, the jury's process encompassed one online expert information session (Table 1). Following a standard CJ process, the jurors received information about the Uusimaa Climate Roadmap and its transport policy measures. They heard experts and discussed the policy measures in small groups. The first session engaged with the effectiveness of the proposed policy measures related to climate targets, while the second session directly discussed justice, focusing on the fairness and social impacts of the measures. The two last sessions focused on preparing a set of recommendations in the form of a statement that was published and presented to the URC in a press conference in May 2022.

| Jury | Day | Phases of the jury | Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transport jury | Day 1, face to face | Initial discussions about the effectiveness of policy measures | Six breakout groups with 5–6 jurors in each group, 2 h per group. |

| Day 2, face to face | Direct discussion on justice | Six breakout groups with 5–6 jurors in each group, 1 h per group. | |

| Online meeting | Expert information session | No collected data | |

| Days 3–4, face to face | Preparing the statement | Five breakout groups with 5–6 jurors, 3.75 h of discussion per group in total. | |

| Final written output | The statement | The is statement available at: https://sites.utu.fi/factor/en/citizen-panel/citizens-jury-on-carbon-neutral-road-traffic-in-uusimaa-region/ | |

| Forest jury | Day 1, face to face | Initial discussions on forest use and related problems | Six breakout groups with 5–6 jurors, 3.5 h of discussion per group. |

| Day 2, face to face | Direct discussion on justice | Six breakout groups with 5–6 jurors in each group, 1 h per group. | |

| Online meeting | Expert information session | No collected data | |

| Days 3–4, face to face | Preparing the statement | Four breakout groups with 8–9 jurors, 3.75 h of discussion per group in total. | |

| Final written output | Statement | The statement is available at: https://sites.utu.fi/factor/wp-content/uploads/sites/948/2022/11/Lapin-metsa%CC%88raati-julkilausuma-saavutettava.pdf |

3.1.2 The Lapland Forest Jury

Lapland, the northernmost region of Finland, has approximately 175,000 inhabitants and covers around 30% of the total land area of Finland (National Land Survey of Finland 2024). Forests cover 98% of the land area, with more than 50% being productive forest land, making forestry and the wood industry significant for Lapland's economy (Natural Resources Institute Finland 2023), further reinforced by the construction of a new biomill in Kemi in 2022. However, these economic activities have been accompanied by growing concerns about declining carbon sinks and biodiversity. The region has also witnessed disputes over land use between the indigenous Sámi people and the state-owned forest management company Metsähallitus, which manages almost two-thirds of the region's forests (Jokinen 2019). In addition to forestry, Lapland's economy relies on tourism, where forests also play an important role. Simultaneously, the emergence of wind farm and mining projects has triggered additional land use conflicts (Sorvali et al. 2023).

In 2021, the Lapland Regional Council (LRC) adopted a “Green Deal” roadmap for Lapland, aimed at guiding the region's sustainability transition (Lapland Regional Council 2021). Sustainable forest use was one of the roadmap's main goals, and the LRC had identified the consolidation of various forest use interests as a challenge in the roadmap's implementation. They sought the perspectives of citizens on this matter and jointly initiated the Lapland Forest Jury with the research team in the Autumn of 2022. The Forest Jury was broadly tasked with providing recommendations for just and climate-smart forest use in Lapland.

We selected the 33 jury members through a stratified two-stage random sampling. We sent invitations to 6000 randomly selected Lapland residents. Among the 240 individuals who volunteered to participate, we randomly picked the jury members using quotas for age, gender, education, and place of residence to form a representative sample of Lapland residents. Additionally, we ensured a balanced representation of both forest owners and non-owners.

The jury convened over two weekends in November 2022. The process encompassed small group discussions and expert hearings during the first weekend, including discussions on forest use and challenges related to current forest uses. During the first weekend, we also held a session directly discussing justice related to forest use. The second weekend focused on the crafting of a joint statement. An online expert information session took place between the face-to-face meetings to address the participants' information needs. The finalized statement was unanimously adopted by the jury and submitted to the Green Transition Committee of Lapland.

The authors of the paper acted as facilitators in the small group discussions in both juries.

3.2 Data and Analysis

We analyzed the recorded and transcribed group discussions and the final statements of both juries (Table 1) using theory-guided content analysis. First, we identified the justice claims related to the dimensions of justice. We focused on understanding how the participants interpreted these dimensions in the specific policy contexts. Using the framework outlined in Figure 1, we discerned the justice-related claims put forward by the jurors and examined how these claims evolved during deliberation. Specifically, we investigated whether certain justice issues became more prominent while others were downplayed. To monitor the development of justice claims, we followed the jury design and analyzed the three distinct phases of the juries: initial discussions, discussions with an explicit focus on justice, and discussions related to working with the statement (Table 1). We identified the justice claims relevant to each of these stages, paying attention to how frequently the same claims were reiterated and whether they gained support among the participants or were mentioned only once. The jurors raised justice issues throughout the discussions. The focused justice discussion functioned as a prompt to consider broader justice aspects, elaborating the justice perspectives compared with the initial discussions. In the analysis, we included all kinds of justice-related claims, regardless of whether the jurors explicitly used words like justice, fairness, or equality. We considered this approach appropriate given the broader task of the juries to provide recommendations on how to enact climate policies in a just manner.

The initial analysis was carried out collectively by all the authors, with each taking responsibility for a part of the data. Subsequently, two authors assumed responsibility for the analysis, ensuring consistency in the identified justice issues and analyzing how the arguments evolved across the different phases. The interpretations were discussed with the other authors to ensure consistency. Based on this analysis, we identified the core justice-related themes and storylines, as well as aspects of justice that were less considered in the discussions. These are reported in the following section. As we analyzed the jurors' verbalized justice concerns and their translation into the final statements, we aimed to avoid giving emphasis on cheap talk about justice that fails to impact on the “realization” of justice in the statement.

4 Results

4.1 The Transport Jury

The transport jury assessed a set of policy measures that aimed to reduce carbon emissions from private cars—such as congestion fees, parking restrictions, and emission fees—and measures that promote public transport, cycling, and walking, and the electrification of road transport (Saarikoski et al. 2023). Despite the focus on specific policy measures, the jury members also envisioned more comprehensive changes that would enable car-free lifestyles.

4.1.1 The Need to Reduce Emissions

Perhaps the biggest question is “Why us”? Why should we reduce emissions when there are much more polluted cities like Beijing?

Nevertheless, these arguments did not influence the final jury recommendations, indicating that some learning regarding different pollutants (such as the difference between particle emissions and CO2 emissions) and the concept of a carbon footprint occurred during the jury discussions (see also Saarikoski et al. 2023).

4.1.2 Deliberating Mobility Needs

The most intensive discussion evolved around access to mobility and the distributive impacts of low-carbon transport policies. The jurors emphasized the importance of ensuring that everyone can meet their daily mobility needs, such as the need to commute to work and school, and the need to access essential services—like healthcare and grocery stores—and leisure activities. This meant that transport should not be excessively expensive or time-consuming, while acknowledging various capacities to use the available modes of transport. This fundamental idea of sufficiency in fulfilling mobility needs was shared among the jurors from the outset; but throughout the discussions, they debated the acceptable levels of inconvenience, costs, and the specific mobility requirements that are deemed essential. The core groups requiring special attention, frequently raised during discussions, included the elderly, children, and families with young children, individuals with mobility limitations (such as disabilities), those in less advantageous socioeconomic positions, the residents of rural areas, and individuals whose mobility needs were influenced by their occupation, including entrepreneurs.

We need carrots, like promoting a cause… I believe that it works better than punishing those who have no other options. Especially if you live in sparsely populated areas, you need a car.

Should people have the right to live wherever they want? Or is it also about sustainability and stuff like how much should society accommodate those who live in very remote areas?

Juror 1: Well, [cycling]is good [cycling]. If you can make it work, it's really great. But for us, it doesn't quite work. My wife's work commute is 30 kilometres one way, and then there is the grocery shopping and other errands.

Juror 2: Yeah, but that's a different matter.

Juror 1: Every time you have to go to a bigger store, it adds up to over 30,000 kilometres a year.

Juror 3: It's like a necessity. A car is a necessity for you.

While the jurors were understanding of various life situations, some situations were seen as more pressing than others. For instance, despite extensive discussion regarding the importance of not making work-related travel too difficult, the transport jury's final statement only suggested waiving congestion fees for those needing a car for work or health-related travel. Similarly, despite widespread concern in the justice-related discussions, the acknowledgment of different socio-economic positions in setting the fee level was merely a question (not a recommendation) in the statement.

4.1.3 Reconciling Emission Reductions and Mobility Needs

The jury discussions revealed two distinct approaches to reconciling the meeting of mobility needs with the imperative to address climate emissions, extending beyond the predetermined policy measures. One approach focused on broader environmental impacts and the affordability of potential solutions, while the other aimed to elevate the transition to a broader level by influencing mobility needs. While both approaches were beyond the scope of the jury's initial mandate, the discussions shed light on the relationship between CJs and the development of just transition policies.

Because buying an electric car is a forty-thousand-euro investment whereas if you do that conversion, it's a one- or two-thousand-euro investment, so it's much more appealing and achievable.

The jurors were provided with information about the life-cycle costs of electric cars, which are considerably lower compared with those of gasoline cars. Nevertheless, the jurors pointed out that high up-front costs are a major obstacle to low-income households. They observed the dynamics that increase inequality among people who can invest in cost-saving technologies, like electric cars, and low-income people who do not have similar opportunities. Consequently, the jury included the biofuel solution in their statement as an affordable interim alternative.

The realization that everyday mobility needs must be met both in urban and rural areas led the jurors to propose structural solutions that extended beyond the transport sector. The idea was to influence mobility needs through improved land-use planning and situating services closer to where people reside, work, or attend school. For instance, it was suggested that children's extracurricular activities should be more closely linked to their schools to reduce the need for private car transportation. Hence, the jury opened up the space to enhance fairness and highlighted the need to take a holistic perspective, including multi-regime interactions, when considering just transition policies.

4.1.4 What Was Less Considered?

And when you consider fairness here, the people in a weaker position, those who can't afford to buy an electric car, they're really hit hard if something isn't done. And then, if you add congestion fees on top of that … my goodness!

However, the fact that not everyone can afford or drive a car even in the present situation was not widely problematized or considered a significant injustice. Car sharing, facilitating the utilization of public transport, cycling, and walking were recognized as increasing mobility justice for those unable to afford a car. Nonetheless, lowering the mobility level of those who currently have access to private cars to match those who cannot afford one was not seen as a viable solution. Instead, a common concern, especially regarding congestion fees, was that they might lead to a situation where only wealthy people could drive into the city center. The mobility needs of those unable to afford any type of car were not recognized as equal to those who could purchase a fossil-fuel car.

While the perspectives of global and intergenerational justice were used to support the general consensus about the necessity of reducing emissions, they were not extensively debated or discussed. Also, arguments about ecological solidarity were absent from the discussions as none of the participants mentioned ecological integrity or the rights of nonhumans as reasons to reduce transport carbon emissions. Furthermore, as the discussions primarily revolved around distributive and recognition justice, procedural justice was only briefly addressed in the context of the jury itself. Additionally, considerations about the diversity and representation of jury members were voiced concerning members' place of residence in comparison with the broader population of Uusimaa.

4.2 The Forest Jury

The forest jury was provided with no predefined policy measures, but it had an open task to craft recommendations for forest use in Lapland, related to three themes: the current state of forest use, the related key problems, and the just use of forests. The LRC hoped to receive constructive suggestions on how to balance diverse forest-use interests. The analysis below highlights the main remarks on justice expressed in these discussions and describes their evolution throughout the jury process.

4.2.1 Consolidating Different Interests and Transparency in Planning

The rationale of multifunctional forestry resonated among the jurors. During the first discussions, they identified a diverse set of interests, including those of berry pickers and leisure users, the forest and tourism industries, the Sámi people, hunters, landowners, reindeer herders, future generations, non-human animals, and nature. Against this backdrop, the jurors pondered the power relations in forest planning, raising procedural justice issues. Some stated that the interests of the affluent forest industry currently override environmental concerns and dominate over other livelihoods, which were seen as unjust. Over the course of the discussions, participatory planning and arbitration were raised as means to balance different interests. Bringing forest users around one table to resolve conflicts of interest resonated among the jurors. In their final statement, they recommended continuing participatory planning practices, which have become more common in natural resource management in Lapland in recent years. The participants agreed that just forest use requires planning procedures that are able to represent and respect all perspectives.

Maybe Metsähallitus”s role should be more transparent and responsible in general. […] Like, how the decisions are made there.

These notions highlight the importance of procedures in the jurors' considerations regarding just forest use. Obscurity in planning was seen to prevent people from assessing whether the outcome, satisfactory or not, was reached through a fair process.

4.2.2 Debating Sustainable Forest Management

Forest management practices received considerable attention when the jurors first discussed the distributive impacts of forest use. Clear cutting, for instance, was criticized because of the long-lasting drawbacks for the landscape, biodiversity, hunting, and leisure use. As the deliberations progressed, opposing views were voiced, too: clear cutting was justified on the grounds that, eventually, the forest grows back. Also, concerns regarding the economic unfeasibility of other forestry methods, like continuous cover forestry, were raised. While many jurors maintained that other methods should be favored over clear cutting, tailoring forest management practices, such as excluding certain areas from clear cutting, also appeared viable.

Overall, carbon sinks and biodiversity emerged as important metrics of distribution in the deliberations, reflecting ecological justice. The meaningfulness of ambitious climate and biodiversity targets was questioned occasionally, but these views often provoked counterarguments and failed to gain broad acknowledgment. The will to protect carbon sinks and biodiversity was also reflected in the jury's final recommendations, indicating various ways to support both aims.

[T]he landowner has the right to decide, up to a point, how to use their forests.

If a private forest owner protects their forest or postpones its logging, they should probably receive some kind of compensation for that.

Could there be some kind of legislation, ensuring that these private companies that capitalise on nature should compensate by investing in some way?

Regardless of the varying emphases on economic versus environmental benefits, many jurors thought that the utilization of the forest resources was dominated by short-term interests. They shared the concern over future generations' possibilities to benefit from forests and highlighted long-sightedness in decision-making. Some jurors noted that the renewal of the Forest Law in 2014 removed the minimum logging diameter for trees, which was seen to incentivize the pursuit of short-term economic gains at the cost of both the economy and the environment in the long term. In the statement, the jurors unanimously recommended the re-adoption of a minimum diameter to reconcile the environmental and timber production goals.

4.2.3 A Sense of Regional Injustice

Well, that is precisely it if Lapland's forests have to compensate for traffic emissions in Helsinki, then that is not fair.

Somewhere in the EU region, the forests have been logged many hundreds of years ago. So, they don't have to restore them. But maybe we do.

Others, however, reminded the jury that state borders are irrelevant from the perspective of emission reductions, and that Finland is more prosperous than many other European countries. Still, the jurors shared a general sense that locals should have more say in the use of Lapland's forests. This sentiment was strong especially at the start of the jury process; but in the final statement, it was not explicitly mentioned beyond mentioning participatory planning. The statement did recommend sharing information about the role of Lapland's forests in climate change mitigation. This recommendation, coupled with notions of regional injustice, reflects the jurors' urge to gain recognition for their home region's efforts in climate change mitigation.

4.2.4 What Was Less Considered?

While the jurors carefully weighed procedural and distributive justice issues, less attention was devoted to individual capacities. The question of socioeconomic inequalities was not touched upon, and the potential constraints of participation in natural resource management and land-use planning processes received scarce attention. Likewise, the global impacts of climate change and mitigation were mentioned a few times, but in general, global justice or distant people's positions were not salient issues. Claims about fair burden sharing between countries were mostly on the EU level and not the global level.

Finally, the absence of mentions of the Sámi in the final statement is worth noting. Discussions about the indigenous people's rights were quite rich in the first weekend, observing historical injustices, such as forced integration and the deprivation of Sámi land. However, some jurors maintained that the rights of the Sámi are already well considered in formal decision-making processes and, therefore, there is no need to stress those any further. During the second weekend, the topic was hardly discussed, and it was absent in the statement, indicating that for the jury, the most pressing issues in forest use pertained to locals' rights in general rather than Sámi rights specifically.

5 Discussion

The experiences from both CJs supported the argument that DMPs can engage with sustainability transition's trade-offs and help to identify just solutions (see, e.g., Pickering et al. 2022; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts 2021). The juries reinforced the utilization of climate emissions as a key metric to consider, thereby acknowledging global and intergenerational justice (cf. Daw et al. 2022). Both juries also demonstrated the important role that expectations play in guiding the understanding of fairness. While the jurors generally attempted to legitimize their expectations taking into consideration global and intergenerational justice, the jurors' expectations led the juries to somewhat downplay the urgency of climate action and to support some measures to maintain the status quo (see also Ciplet and Harrison 2020; Bowden et al. 2021; Huttunen et al. 2024). Assessed against the multiple issues connected to just transitions (see, e.g., Tribaldos and Kortetmäki 2022; Kivimaa et al. 2023), the transport jury emphasized distributional and recognition justice while the forest jury focused more on procedural justice. Below, we discuss the core lessons related to what becomes of justice in deliberations, the role of framing of the task, and the limitations of the juries.

5.1 Doing Justice in Deliberation

The results support the assumption that deliberation can foster the consideration of interests extending beyond individual and immediate economic concerns (Grönlund et al. 2020; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts 2021; Willis et al. 2022). In the transport jury, the jurors endorsed the need for reducing transport emissions and justified this with concern for future generations and global responsibility. The arguments that carbon emissions should be tackled elsewhere, put forward in the first jury sessions, did not make their way to the final recommendations, suggesting that the jurors assumed more responsibility for global climate change mitigation. In the forest jury, climate mitigation and biodiversity protection were considered important, and the dominating role of commercial forestry was questioned. However, the jury also emphasized equality in climate mitigation responsibility: Lapland's forests can be carbon sinks, but simultaneously, emissions need to be cut elsewhere—Finland's regions should bear equal responsibility for mitigating climate change.

Besides fostering understanding of the need to reduce emissions, the transport jury increased the participants' understanding of diverse capacities and vulnerabilities related to the transition. Metrics, such as income and mobility needs in rural areas, were applied to justify the continuity of affordable private driving. Furthermore, subjective expectations regarding the legitimacy of certain lifestyles, such as living in remote areas and depending on affordable cars, were employed to rationalize the continuity of private motoring and the current level of mobility possibilities. These arguments further encouraged the jurors to emphasize supportive measures, such as improved public transport, as an important element of just carbon-neutral transport, instead of measures limiting the possibilities to use private cars in rural areas. The reluctance to propose radical measures demonstrates that deliberation outcomes can also conflict with ambitious climate policies as they become seen as unjust (see also Bowden et al. 2021).

In the forest jury, timber production was considered a legitimate source of livelihood despite the challenges regarding biodiversity and climate change mitigation. Restrictions on private forest owners' forest management choices and loss of income were understood to be a legitimate basis for compensation. This resulted in recommendations supporting and encouraging the owners to protect biodiversity and carbon sinks rather than strict requirements and related sanctions. The emphasis on forest owners' rights is a common principle for determining access to forest resources. In addition, it is often regarded as necessary to acknowledge the rights, expectations, and needs of local communities (Forsyth and Sikor 2013; Hoang et al. 2019), including those of the forest itself, to guarantee the existence of the forests (Meriläinen and Lehtinen 2022). Similar to the transport jury's recommendation for supportive and enabling measures, the compensation for private forest owners and supportive measures were seen as ways to balance the legitimate expectations in the jury process.

The transport jury demonstrated how a jury deliberation can provide deeper insights on the potential and practical impacts of transition policies on people's well-being and daily lives (cf. Daw et al. 2022). This especially occurred by emphasizing the different opportunities for a car-free lifestyle in urban and rural areas and for shifting to electric cars. The accounts of jurors living in rural areas with long distances to travel to services and limited or no public transport connections made it clear that most of the policy measures, such as road tolls or parking restrictions, are unfeasible outside the Helsinki metropolitan area. Similarly, the buying costs of electric cars made them an unfeasible alternative for many. To meet the objectives, the jury looked for more creative solutions beyond those proposed by the URC, including biofuels and influencing the mobility needs themselves. Thus, besides identifying practical impacts, the jury also brought forward new ideas to reach more just outcomes, which adds an important aspect to the potential benefits of CJs.

The forest jury showcased the capacity to go beyond vested interests and emphasize the common good (c.f. Pickering et al. 2022; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts 2021). Reflections about the appropriate balance between public and private interests especially took place when the participants discussed the role of forestry and private forest owners' rights and duties. The jury highlighted that one industry dominating over all the others is unjust. Furthermore, the jury indicated support for burden sharing according to the “beneficiary pays” and “polluter pays” principles. A key outcome of the deliberation was the acknowledgment of the multiplicity of forest uses and the right of all forest users to be heard, resulting in an emphasis on inclusive and transparent forest land-use planning procedures. In a situation where legitimate interests are at odds, the procedures of decision-making play a special role in ensuring fairness (cf. Esaiasson et al. 2019). However, the emphasis on procedural justice can also be interpreted as an attempt to circumvent the difficult balancing task the jurors found themselves faced with, transferring the actual balancing to planning situations.

5.2 The Role of Framing the Tasks and Limitations

Both examples highlight the formative agency (Dryzek and Tanasoca 2021) of the juries in formulating the meaning of fairness in the policy contexts and in proposing solutions that are able to account for the conflicting interests or poorly understood practical limitations of everyday life. However, the juries differed in terms of their subjects and the framing of their tasks, which somewhat influenced the deliberations. In the transport jury, the pre-given agenda directed attention to specific transport policy measures, while the forest jury had a more open framing to consider the utilization of forests. As was also noticed by Wells et al. (2021) in relation to juries conducted in the United Kingdom, the pregiven measures make the transport jury appear more as a consultative process with limited room for citizens to influence the agenda, which the participants also criticized. While the focus on specific policy problems has generally been connected to the effectiveness of DMPs in providing clear recommendations (Bryant and Stone 2020), in justice deliberations, broad framings can facilitate more innovative thinking. Despite its broad framing, the forest jury provided specific policy recommendations, and the openness enabled the jury to address justice in broader terms, including consideration of processes with which to reach better solutions. Had the transport jury been given more space to consider how to reduce emissions in a just manner, instead of considering predetermined policy measures, it might have been able to produce more innovative solutions and enact its formative agency more effectively.

Furthermore, the transport jury's specific focus on an issue affecting the everyday life of the participants may have reinforced the jurors' expectations related to maintaining the current level of mobility, which was a clear limitation for its capacity to consider global justice (cf. Daw et al. 2022). The forest jury's task was more distanced from the everyday life of the participants, which enabled it to consider more broadly the general good in terms of climate mitigation and biodiversity. This implies that the choice of subject may influence the way justice becomes understood within DMPs.

The unaddressed justice issues give indications about the capacities of the juries to deal with potential epistemic injustices and raise the voices of disadvantaged and marginalized groups. The juries distilled the most important concerns of an average citizen, but both juries lacked in-depth consideration of vulnerable groups such as those economically most disadvantaged in the transport jury or the indigenous Samí people in the forest jury. Involving vulnerable groups has been an acknowledged issue in DMPs and solutions such as enclave deliberation have been proposed (Karpowitz et al. 2009; Ross et al. 2021). Our study further emphasizes this need: when aiming to use DMPs to facilitate justice in transitions governance, the inclusion of vulnerable perspectives becomes pertinent; otherwise, the juries can just reinforce existing power relations.

Finally, our approach focused on analyzing the justice issues raised during deliberative processes and how these were shaped into the final statements. While the jurors highlighted the issues they found important, some concerns may have gone unspoken, and others may have been voiced simply because the participants believed they were expected to mention them. However, the task of creating a statement likely ensured that the core shared justice issues persisted. Hence, it is likely that our analysis can show how justice develops in deliberation.

6 Conclusions

We analyzed the ways two CJs deliberated justice in the context of climate transitions. Our results demonstrate the capacity of CJs to tap into citizens' lived experiences and explicate the important role that people's expectations play in guiding their justice claims. The CJs were successful in creating an understanding of justice in relation to the climate issue they faced. Both juries' understanding of justice focused on the immediate issues, with less attention paid to global and marginal perspectives. Although the justice considerations may be context specific, our research highlights the following lessons for CJs dealing with sustainability transitions.

First, the important role of participants' expectations in influencing their justice claims suggests that the legitimacy of these expectations requires attention from policymakers. This means focusing more on epistemic environments and the information based upon which people form their expectations: do they, regardless of the transition, have legitimate reasons to believe in the continuation of their livelihood or lifestyle? Our results suggest that CJs could have epistemic potential to support the formation of more informed and consistent (i.e., more legitimate) expectations.

Second, to support the epistemic potential of the CJs, the framing of the task should be broad enough to enable jurors to address justice more comprehensively and facilitate the potential for innovative solutions. In relation to this, policymakers and other jury organizers should pay more attention to including the perspectives of vulnerable groups in justice deliberations. This can happen by modifying the jury design to include them as participants, knowledge providers, or by complementing the CJs with other participatory methods in the policymaking processes.

Involving citizens in just transitions governance is fundamental for reaching more just solutions. As CJs provide an increasingly applied means for citizen engagement, particularly in the EU context, it is important to acknowledge that the juries produce a particular understanding of justice and just transitions reflecting the design of the jury process and the task given to the juries. While highly useful, the juries represent only one participatory method that needs to be complemented by others.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants of the citizen juries for their valuable contribution to the jury processes. We acknowledge the Research Council of Finland (Project No. 341398) and the Strategic Research Council (Project No. 358410) for financial support. Open access publishing facilitated by Suomen ymparistokeskus, as part of the Wiley - FinELib agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.