Overview of causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abbreviations

-

- AP

-

- alkaline phosphatase

-

- DILI

-

- drug-induced (or herbal/dietary supplement–induced) liver injury

-

- DILIN

-

- Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network

-

- RUCAM

-

- Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Model

-

- ULN

-

- upper limit of normal

The diagnosis of drug-induced (or herbal/dietary supplement–induced) liver injury (DILI) remains largely a diagnosis of exclusion. Research into diagnostic serum markers has made great progress, but few markers have made it into clinical use. For now, two diagnostic methods are in widest use: the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Model (RUCAM) and expert consensus opinion.1, 2 Only the former is available to the clinician. Both methods have obvious weaknesses, and developing a better diagnostic is a clear mandate.

Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Model

The RUCAM is an algorithmic scorecard published in 1993 to clinically diagnose DILI. Eight experts from six countries subjectively built the algorithm (Table 1) based on published literature. The clinician first decides whether the injury is hepatocellular or mixed/cholestatic. By convention this decision is based on the r value: alanine aminotransferase/upper limit of normal (ULN) ÷ alkaline phosphatase/ULN. The r values > 5 are hepatocellular, 2 to 5 are mixed, and <2 are cholestatic.

| Criteria | Hepatocellular | Cholestatic or Mixed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Time to onset | Initial Exposure | Subsequent Exposure | Points | Initial Exposure | Subsequent Exposure | Points |

| Timing from: | 5-90 da. | 1-15 da. | +2 | 5-90 da. | 1-90 da. | +2 |

| Drug start | <5, > 90 da. | >15 da. | +1 | <5, > 90 da. | >90 da. | +1 |

| Drug stop | ≤15 da. | ≤15 da. | +1 | ≤30 da. | ≤30 da. | +1 |

| 2. Course | Difference between peak alanine aminotransferase and ULN value | Difference between peak alkaline phosphatase (or bili) and ULN | ||||

| After drug cessation | Decrease ≥50% in 8 da. | +3 | Decrease ≥50% in 180 da. | +2 | ||

| Decrease ≥50% in 30 da. | +2 | Decrease < 50% in 180 da. | +1 | |||

| Decrease ≥50% in > 30 da. | 0 | Persistence or increase or no info | 0 | |||

| Decrease < 50% in > 30 da. | −2 | |||||

| 3. Risk factors | ||||||

| Ethanol/pregnancy | Ethanol: yes | +1 | Ethanol or pregnancy: yes | +1 | ||

| Ethanol: no | 0 | Ethanol or pregnancy: no | 0 | |||

| Age (years) | ≥55 | +1 | ≥55 | +1 | ||

| <55 | 0 | <55 | 0 | |||

| 4. Other drugs | None or no info | 0 | None or no info | 0 | ||

| Drug with suggestive timing | −1 | Drug with suggestive timing | −1 | |||

| Known hepatotoxin with suggestive timing | −2 | Known hepatotoxin with suggestive timing | −2 | |||

| Drug with other evidence for a role (e.g., + rechallenge) | −3 | Drug with other evidence for a role (e.g., + rechallenge) | −3 | |||

| 5. Competing causes | All of group Ia and IIb ruled out | +2 | All of group Ia and IIb ruled out | +2 | ||

| All of group I ruled out | +1 | All of group I ruled out | +1 | |||

| 4 to 5 of group I ruled out | 0 | 4 to 5 of group I ruled out | 0 | |||

| <4 of group I ruled out | −2 | <4 of group I ruled out | −2 | |||

| Nondrug cause highly probable | −3 | Nondrug cause highly probable | −3 | |||

| 6. Previous information on hepatotoxicity of the drug | Reaction in product label | +2 | Reaction in product label | +2 | ||

| Reaction published; no label | +1 | Reaction published; no label | +1 | |||

| Reaction unknown | 0 | Reaction unknown | 0 | |||

| 7. Response to repeat administration | Positive | +3 | Positive | +3 | ||

| Compatible | +1 | Compatible | +1 | |||

| Negative | −2 | Negative | −2 | |||

| Not done or not interpretable | 0 | Not done or not interpretable | 0 | |||

- a Group I: hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus (acute), biliary obstruction, alcoholism, and recent hypotension (shock liver).

- b Group II: cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and herpes virus infection.

- Adapted with permission from Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.1 Copyright 1993, Elsevier.

Thereafter, seven criteria are scored. First and most important is time to onset, or latency, which categorizes time from start, or end, of drug exposure to onset of hepatotoxicity. Next, the course of reaction, or washout, is scored, with more rapid decline in liver enzymes garnering more points. The RUCAM scores each suspected agent. So the fourth criteria addresses cases with more than one agent implicated, penalizing if other suspicious agents weigh in against the agent being scored. The non-drug-related causes criteria give or take points depending on the thoroughness of excluding non-DILI diagnoses. Next, previous information on hepatotoxicity for a particular agent is assessed, giving more points for drugs more likely to cause liver injury. Finally, response to readministration is scored, although such rechallenge is rare. All scores are totaled with sums falling into subjective categories of likelihood (Table 2).

| Category | RUCAM Sum Score |

|---|---|

| Highly probable | >8 |

| Probable | 6 to 8 |

| Possible | 3 to 5 |

| Unlikely | 1 to 3 |

| Excluded | <1 |

Although straightforward in principle, RUCAM scoring instructions are ambiguous. For example, should the r value be calculated at onset or at peak level of enzyme elevation? For latency, should the time from drug start, or drug stop, or both be scored? The terms “alcohol exposure” and “known hepatotoxin” are not clearly defined. These ambiguities lead to RUCAM's poor interuse and intrauser reliability in exact score agreement.3 However, agreement on the five categories of likelihood is better. Validation using published rechallenge cases was done, but legitimacy of using such cases for validation is unclear.4, 5

Nevertheless, RUCAM remains a valuable tool for the clinician by providing a starting point for evaluating DILI. It highlights areas of diagnostic importance and requires the precise delineation of latency and course that is so critical in diagnosis. Also, RUCAM's positive predictive value for discerning at least probable DILI compared with expert opinion (described next) is excellent at 95%.6 Negative predictive value is poor at 23%. Thus, RUCAM is good at identifying DILI, but poor at ruling it out.

Expert Consensus Opinion

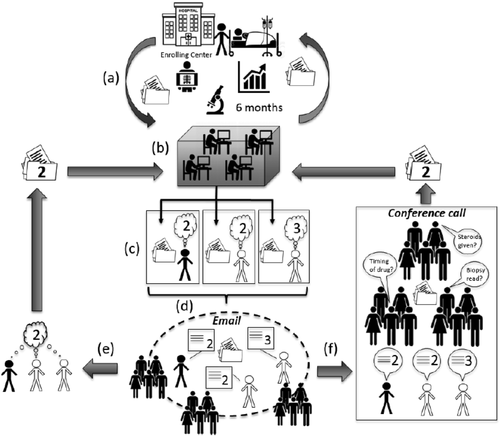

Partly because of RUCAM's shortcomings, the US Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) developed a consensus expert opinion process to support a registry of well-vetted DILI cases (Fig. 1). Although unavailable to the clinician, it is arguably the best way of identifying DILI cases for clinical and bench research. The DILIN has included six to eight centers over more than a decade. The investigators at each site enroll cases and gather clinical data and blood samples for 6 months. All the data are submitted to a central coordinating center that then generates a standardized narrative and summary form that includes tables of laboratory values, concomitant medications, and clinical history. These are distributed electronically to three DILIN investigators, one from the enrolling site and two chosen at random from other sites. Each reviewer has 2 weeks to independently assign a subjective score from 1 to 5, each score corresponding to a percentage likelihood range (Table 3). Each implicated agent is similarly scored.

Diagram of DILIN expert consensus opinion process. (A) Enrollment and data gathering occur through the enrolling medical center. (B) Six months of data are collated and put into standardized forms at the data coordinating center. Forms released to three assigned DILIN investigators by secure Web site. (C) Three investigators have 2 to 3 weeks to independently assess the case. In this example, two reviewers assign the case a 2 (highly likely DILI), but one reviewer considers it a 3 (possible DILI). (D) Four days of e-mail discussion ensues, which may include all DILIN investigators. (E) If agreement is reached by e-mail, the case is closed and logged. (F) If no agreement is reached, the case is formally presented and discussed by teleconference among all DILIN investigators to reach resolution.

| Score | Category | Likelihood | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Definite | >95% | Beyond reasonable doubt |

| 2 | Highly likely | 75% to 95% | Clear and convincing, but less than definitive |

| 3 | Probable | 50% to 75% | Preponderance of evidence support |

| 4 | Possible | 25% to 49% | Not supported by preponderance of evidence but cannot exclude |

| 5 | Unlikely | <25% | Highly unlikely based on evidence |

One Monday a month, case data, reviewers, and scores are released to all DILIN investigators for 4 days of e-mail discussion. If consensus is reached by e-mail, the case is closed and recorded. If consensus cannot be reached, a teleconference occurs that Thursday for formal case presentation and discussion. If necessary, a vote is taken to resolve persistent disagreements: one vote per center and majority prevails. Individual expert opinion has poor interrater reliability, but the DILIN's consensus protocol improves retest reliability substantially.7 However, there are no validity data for this process, and most of all, it is cumbersome, expensive, and not available to the clinician.

Toward a Better Diagnostic Instrument

Operational ambiguity for the RUCAM and inaccessibility for expert opinion summarize each method's major shortcomings. Going forward, two approaches are being taken. First, the RUCAM provides a good foundation to support a long overdue update by experts in the field. Unlike RUCAM's originators, we now have mature registries of well-documented cases that can inform decisions on which criteria to keep and how to better weight the scores. Also, the ambiguities can be clarified, leading to wider acceptance and reliability. Keeping with RUCAM's original purpose, a revision should provide a clinician-friendly tool for all suspected DILI cases. Second, the DILIN's robust database offers the opportunity to allow the computer to lead the way. Rather than staying within a set framework of subjective parameters, the computer can determine the most important criteria and weighting by sophisticated modeling. Preliminary efforts suggest that such modeling may be best at making separate tools for particular medications with well-known injury patterns (e.g., isoniazid).8

Summary

The RUCAM remains the best diagnostic tool available to the clinician. It provides a solid framework that reminds clinicians of necessary diagnostic information. Compared with expert opinion, it can identify DILI very well, but cannot rule it out. The DILIN's expert consensus opinion remains a research tool, but may be the turnkey toward better diagnostic methods by providing valid and robustly documented cases for analyses. Indeed, growing registries of cases across the globe create an opportunity and mandate to move forward by either building on the current RUCAM or developing a computer-driven instrument de novo.9, 10