Vascular Neoplasms of the Liver

Abstract

Answer questions and earn CME

Abbreviations

-

- EHE

-

- epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

-

- HHV8

-

- human herpes virus 8

-

- KS

-

- Kaposi sarcoma

The main vascular tumors of the liver include hemangioma, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE), and angiosarcoma. They develop in noncirrhotic livers and are increasingly being detected incidentally by imaging. All of these tumors express markers of vascular lineage, such as ERG, CD31, and CD34. The purpose of this review is to highlight the main pathological aspects of these tumors.

Hemangioma

Hemangioma is the most common benign hepatic vascular neoplasm and is usually found incidentally on imaging studies.1, 2 Women are most commonly affected, but the cause is unknown. Although patients may be asymptomatic, clinical manifestations may also include hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, anemia, and high-output congestive heart failure.3 Hemangiomas often follow a benign course, and a nonoperative approach is recommended unless the patients are symptomatic or have large tumors.1

Grossly, hemangiomas are well-circumscribed, dark brown, and spongy tumors. They can be focal lesions or affect the liver diffusely with multiple foci; the diffuse pattern is also termed hemangiomatosis and can clinically mimic metastases.4, 5 There are three histological subtypes of hepatic hemangiomas: cavernous, lobular, and anastomosing.

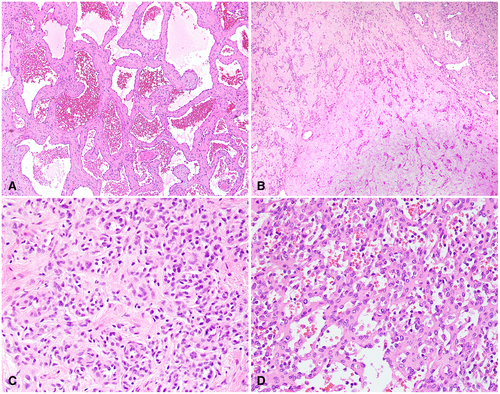

Cavernous hemangioma, the most common of these subtypes, is composed of variably sized, dilated vascular channels surrounded by interspersed fibrous tissue. The vessels may be thick but do not have muscular layers and are lined by flat endothelial cells without atypia (Fig. 1A). It is speculated that when the vascular spaces of cavernous hemangiomas collapse and regress, they then become sclerosing hemangiomas6 (Fig. 1B). Areas of scarring and occasional calcification may be present adjacent to conventional components of cavernous hemangioma.

Lobular capillary hemangioma is the second most common subtype. It consists of numerous capillary-like vessels lined by endothelial cells. No cytological atypia or mitoses are present (Fig. 1C). Infantile hemangioma, which is also known as infantile hemangioendothelioma, is a form of capillary hemangioma that occurs in infancy or early childhood.7

Anastomosing hemangioma is a rare, recently recognized variant characterized by interconnecting capillary-sized vessels that are lined by scattered hobnail endothelial cells. Although the tumor can simulate angiosarcoma because of its hypercellularity, the cells are relatively uniform, and cytological atypia is absent or mild (Fig. 1D). Nevertheless, the histological similarities between the two entities can pose a diagnostic dilemma in needle core biopsies.8

Hepatic KS

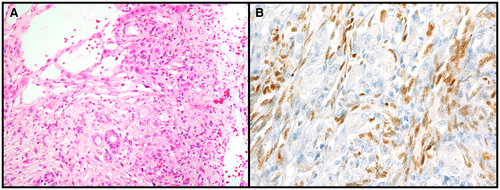

Hepatic KSKS is caused by human herpes virus 8 (HHV8) infection. It occurs most often in male patients with a history of immunosuppression, transplant, or human immunodeficiency virus infection. On autopsy or surgically resected liver specimens, KS is characterized by dark reddish areas around the portal tracts, as well as multiple red lesions in the background parenchyma. On microscopy, KS is composed of spindle cells with bland nuclei that interlace with one another (Fig. 2A). The cells are often centered around portal tracts and can dissect between collagen fibers and surround bile ducts. HHV8 positivity is confirmatory (Fig. 2B).9

EHE

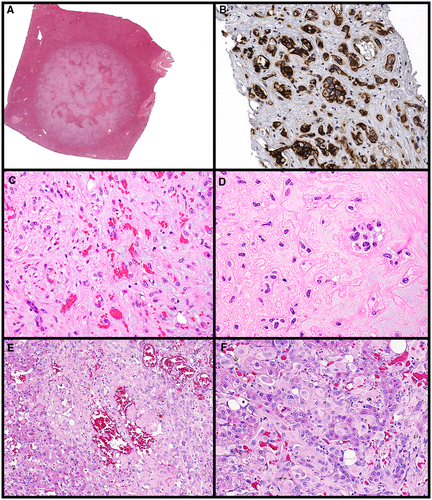

EHE is considered a low-grade malignancy that is more common in middle-aged women. Recent molecular characterization has shown defining translocations such as CAMTA1-WWTR1 fusion (most common) and a subset of EHE with YAP1-TFE3 fusion.10 Grossly, livers affected by classic EHE have multifocal, white, firm nodules that affect the periphery and subcapsular aspects. The tumors have ill-defined, blurred borders as they interface with the surrounding parenchyma (Fig. 3A). The EHE variant that has YAP1-TFE3 may have well-defined liver nodules. On microscopy, classic EHE (with CAMTA1-WWTR1 fusion) often is centered around a feeding vessel and has a dense, fibrotic, or myxoid stromal matrix. The tumor cells are epithelioid, have occasional intracytoplasmic lumens containing red blood cells, but do not form actual vessels (Fig. 3C, D). The neoplasm invades sinusoids and larger vessels; they can form papillary tufts that mimic carcinoma. Vascular markers help confirm the lineage of the tumor (Fig. 3B), but CAMTA1 immunohistochemistry can also confirm the diagnosis of EHE.11 The subset of EHE that has YAP1-TFE3 fusion has more mature vessel lumen formation compared with classic EHE; it is unclear whether the tumors harboring the YAP1-TFE3 fusion represent a true subtype of EHE or are merely a distinct tumor type (Fig. 3E, F).

Angiosarcoma

Hepatic angiosarcoma is a rare and aggressive malignancy that accounts for 0.1% to 2% of all primary liver malignancies.12 Patients present in their 60s and 70s, with a male-to-female ratio of 3-4:1. Risk factors associated with angiosarcoma include radiation/radiotherapy, thorium dioxide, arsenicals, vinyl chloride, androgenic anabolic steroids, hemochromatosis, and von Recklinghausen disease.12 The prognosis is bleak, and patients usually die within 6 to 12 months.13

Grossly, hepatic angiosarcomas may present variably as a large dominant mass, multiple nodules, a mixture of dominant mass with nodules, and rarely, a diffusely infiltrating micronodular tumor.14 The border of the tumor is ill-defined. The surface of the tumor is often heterogeneous, consisting of solid grayish-white areas and/or cystic changes that intermingle with hemorrhage and/or necrosis.

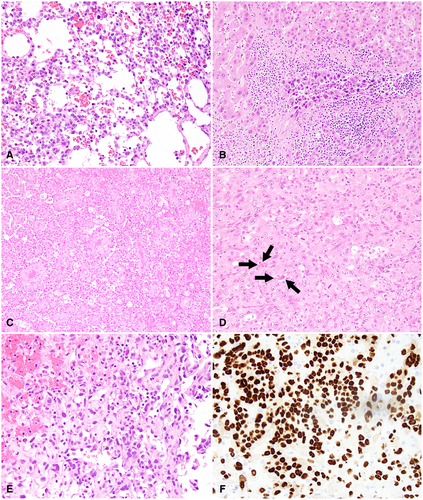

Angiosarcoma is notorious for its ability to display a wide morphological spectrum, ranging from well-differentiated vascular channels to a poorly differentiated solid lesion of vaguely slit-formed vessels. Well-differentiated angiosarcoma is characterized by dilated sinusoidal spaces lined by flat, cuboidal, or hobnail endothelial cells with minimal or mild cytological atypia (Fig. 4A). The other end of the spectrum is the poorly differentiated angiosarcoma that is often highly cellular and forms solid nests or sheets. Angiosarcoma cells grow along vascular channels, replace normal endothelial cells, invade into sinusoidal spaces, and displace hepatic plates (Fig. 4B). Formation of complex vascular structure is common and can be striking, which indicates the lineage of the tumor (Fig. 4C). In solid areas, vasoformative structures are sparse and inconspicuous, which leaves a subtle hint for the origin of the tumor (Fig. 4D). The tumor cells are pleomorphic and are epithelioid (Fig. 4D) or spindled (Fig. 4E) with high-grade cytological atypia. Bizarre multinucleated cells are commonly seen. Mitoses, even atypical ones, are brisk.

Conclusion

We provide an overview of hepatic vascular tumors with a focus on histomorphological features. Complex growth patterns, degrees of cytological atypia, infiltrating border, and lymphovascular invasion are key features that distinguish among benign, intermediate, and malignant hepatic vascular tumors. Table 1 provides a summary of each entity and points of clinical and diagnostic importance.

| Entity | Clinical Associations | Important Histological Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Hemangioma |

|

|

| KS |

|

|

| EHE |

|

|

| Angiosarcoma |

|

|