Insider perspectives on growth: Implications for a nondichotomous understanding of ‘sustainable’ and conventional entrepreneurship

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to offer an alternative to a priori theorising in research on firm-level growth and environmental sustainability. We outline an approach that combines John Shotter's phenomenology with post-hoc application of the Bourdieusian concepts of habitus, practices and social capital. This is illustrated empirically through a study conducted with a small group of Finnish entrepreneurs, which examines their lived experience of growth alongside its practical application in their ventures. The entrepreneurs' responses reveal holistic perspectives on growth that extend beyond the economic to incorporate personal commitments to norms of collectivity and well-being for themselves and others. The paper offers an exploratory but empirically grounded approach, arguing that a combination of insiders' perspectives and attention to the social embedding of economic activity challenge the dichotomous distinctions between sustainable and conventional entrepreneurship and reveal a degree of commonality that would not be evident via conventional categorisations on the basis of features such as business model type.

1 INTRODUCTION

The sustainable entrepreneurship literature lacks a critical theoretical engagement with firm-level growth. For example, a recent, extensive review of the field, (Muñoz & Cohen, 2018) identified just two papers that address the issue explicitly: Choi and Gray (2008) investigated managerial decisions at different growth stages, while Vickers and Lyon (2014) examined growth strategies of environmental social enterprises. This is surprising, given the focal role of economic growth in long-standing sustainability debates, from environmental limits to growth (Meadows, Goldsmith, & Meadows, 1972), and steady state economics (Daly & Cobb, 1989), to more recent variants, such as ‘doughnut economics’ (Raworth, 2017). It has also resulted in two seemingly incompatible discourses. In the dominant ‘green growth’ literature, smaller enterprises and start-up ventures are viewed as ‘drivers’ of sustainable development, delivering continued economic expansion, while also addressing environmental imperatives (e.g., Klapper & Upham, 2015; Mazur, 2012; OECD, 2015). By contrast, in decroissance (‘de-growth’) economics, they are typically presented as low-growth hybrids, pursuing a broader vision of ‘sustainable prosperity’ within localised business models (Cosme, Santos, & O'Neill, 2017; Jackson, 2016). Underlying this debate is an assumption that societies have to manage three nonsubstitutable types of capital, economic, social and natural, whose consumption might be irreversible (Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002).

These issues are exacerbated by previously identified limitations in the mainstream entrepreneurship literature (Leitch, Hill, & Neergaard, 2010). Critical reviews of the field have demonstrated how the dominant discourse of entrepreneurial growth and associated biological metaphors have shaped research approaches, public policy interventions and cultural representation of entrepreneurial activity (Clarke, Holt, & Blundel, 2014; Schmelzer, 2016). There is also evidence of a disconnect with the lived experience of business owners and managers. As Achtenhagen, Naldi, and Melin (2010) observe, parameters and definitions are often determined a priori by researchers, neglecting practitioners' experience, defined in their own terms. As a consequence, researchers risk asking the ‘wrong questions’ about growth, while policymakers continue to work with the ‘wrong assumptions’ (Achtenhagen, Naldi, & Melin, 2010, p. 289).

The absence of practitioner voices also raises important questions for sustainable entrepreneurship research, including its engagement with the issue of growth. For example, as Cyron and Zoellick (2018, p. 209) indicate, the recent degrowth literature remains silent on the nature of growth in ‘postgrowth’ organisations, yet these novel contexts demand a refocusing on the, ‘qualitative aspects of development that reflect the understanding of business growth among practitioners’ (Cyron & Zoellick, 2018, p. 223—emphasis added). We address these gaps in the literature with the following research questions: how do entrepreneurial practitioners conceive of growth in relation to their businesses and what other concepts do they associate with the concept of growth? By drawing on this evidence, we also ask: what inferences can be drawn, in terms of the nature of sustainable entrepreneurship, from conventional entrepreneurial understandings of growth?

To explore these questions, we developed a four-fold hermeneutic research design, which build on a methodological approach adopted by Anderson, Dodd, and Jack (2010) to explore the social nature of growth and the role of networking. The exploratory phase, comprising two e-postcard and LinkedIn surveys, was followed by the main study, which included a roundtable discussion and a series of semistructured interviews with a small, illustrative set of Finnish entrepreneurs. We then completed a five-stage analysis process using a combination of manual and software-based coding methods in order to identify and probe the emerging themes.

By choosing this approach, we aim to document insiders' perspectives on firm-level growth and environmental and social sustainability, recognising that they are the product of complex, situated and idiosyncratic learning processes (Macpherson & Holt, 2007). As the authors note, in this context, both ‘the experience, and active application of that experience by entrepreneurs, is an essential characteristic of growth’ (ibid., p. 185—emphasis added). Accordingly, we also respond to their call to adopt epistemological approaches that are, ‘sensitive to these relational qualities, such as activity theory and practice theory’ (ibid., p. 185).

The findings challenge overly simplistic distinctions between ‘sustainable’ and ‘conventional’ entrepreneurship. For example, the entrepreneurs' experience and practice incorporates conceptions of ‘the good life’ that are closely connected to environmental sustainability (Rosa & Henning, 2018). They reveal a collective dimension to the way that firm-level growth is viewed and lived and additional insights into the entrepreneurs' concern with ‘softer’ facets of growth such as well-being and emotions. While they are not readily generalisable, these findings demonstrate how a practice-based, practitioner-focused approach can shed new light on firm-level growth when these a priori assumptions are removed.

In terms of structure, we first introduce a phenomenological philosophy, Shotter's ‘withness’ thinking and explain how the concept of lived experience has been applied to offer an insider's perspective on growth. We connect this with Bourdieusian concepts in order to highlight the affective dimensions of the entrepreneurs' habitus, practices and approach to social capital, recognising that their economic activity has an also inherently social dimension. The methodological approach is followed by an overview of the findings, which reveal overlaps in conventional and sustainable entrepreneurship at a normative level. We conclude by highlighting the relevance of the study for sustainable entrepreneurship research and implications for policy.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK—ENTREPRENEURIAL GROWTH AS PRACTICE

2.1 Entrepreneurship as socially embedded

In their critical review of the sustainable entrepreneurship literature, Muñoz and Cohen (2018, p. 317) call for a more ‘integrated conception of entrepreneurial action’, along with a reappraisal of the assumptions and normative frameworks that have guided research in this area. This requires the replacement of conventional triple bottom line (‘3BL’) definitions that seek to balance between environmental, economic and social dimensions, with an alternative theoretical framing, ‘recognizing that all entrepreneurs are embedded in economies, society and ultimately natural systems’. (Muñoz & Cohen, 2018, pp. 317–318—emphasis added). As a consequence, the authors argue that sustainable entrepreneurship scholars need to: ‘stretch the boundaries of entrepreneurship in ways that will effectively challenge assumptions of entrepreneurs as rent-seekers’ (Muñoz & Cohen, 2018, p. 318).

We respond to this challenge by presenting a more integrated understanding of entrepreneurial growth, mobilising the sociological perspective outlined by Bourdieu (1986, 2005), in which markets are studied as fundamentally social phenomena. A Bourdieusian approach differs from prevailing understanding of entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviour, which draw primarily on cognitive psychology and market economics. The latter is typically oriented around constructs such as entrepreneurial attitudes, motivations, personality traits, subjective norms and perceived self-efficacy (e.g., Hermans et al., 2015; Stam, Hartog, van Stel, & Thurik, 2012). Yet while variable-based cognitive studies can be a source of potentially useful abstract models, they cannot supply the rich, integrated accounts of the lived experience of growth that are required for our purpose.

2.2 Shotter's phenomenology

Our research framework builds on a phenomenologically inspired tradition in organisation studies (Gill, 2014) that seeks to understand entrepreneurial practice ‘from the inside’ (Gartner, Stam, Thompson, & Verduyn, 2016). As a particular form of interpretative inquiry, phenomenological research seeks to add a richness and depth to accounts of entrepreneurship (Cope, 2005). The approach reflects the value of interpretive social science in this context, from which perspective the entrepreneur is viewed as more than a unit of economic activity or as a fixed entity with implicit or explicit personality traits (Warren, 2004). Viewing entrepreneurship instead as a complex, dynamic, field that involves lived experience, researchers have made the case for appropriate perspectives and methodologies, such as the study of narratives, discourses and phenomenonological inquiry (Anderson, Dodd, & Jack, 2010; Cope & Watts, 2000; Rae, 2000). Here, we use Shotter's (2006) phenomenology to underpin research of the ‘lived experience’ of entrepreneurial growth. Shotter calls this ‘thinking-from-within’ or ‘withness thinking’ (Shotter, 2006, p. 585). This implies a need to seek to understand the patterns of events not only from perspectives of systematic observation and (where possible) control but also from actors' perspectives. Transferred to the context of entrepreneurial growth research, it calls for what Shotter (2006, p. 585) describes as a, ‘kind of responsive understanding that is only available to us in our relations with living forms’, here entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial growth, when ‘we enter into dialogically structured relations with the latter’.

2.3 A Bourdieusian view

2.3.1 Making connections

Following Gartner et al. (2016, p. 818), we adopt a practitioner-based perspective in which, ‘an entrepreneurship practitioner carries patterns of bodily behaviour, but also of certain routinized ways of understanding, knowing how and desiring, for and about, entrepreneurship’. Bourdieu's thinking lends itself to framing an empirical probing of these issues precisely because it views economic activity, social structure, the inherited disposition and emotional life, as well as the skill-set of the individual as intimately connected (Tatli, Vassilopoulou, Özbilgin, Forson, & Slutskaya, 2014). We next provide a brief overview of the main elements of his thought applied in this study.

2.3.2 Habitus

Bourdieu ([1989] 1996, p. 1) held that there is a close relationship between ‘social structures and mental structures, between the objective divisions of the social world … and the principles of vision and division that agents apply to them’. The latter is particularly important here, as entrepreneurs, their perceptions and their practices are a part and parcel of their social habitus. From a Bourdieusian perspective, they are conditioned by, yet also enact the very habitus of which they are a part. Their apparently idiosyncratic, voluntaristic acts are shaped by the nature of the coupling to the environment, that is, the everyday structures and the entrepreneurial sense-making of those structures. As Gieser (2008, p. 301) suggested Bourdieu's work (Bourdieu, 1977, 1992) ‘inspired a new interest in the social nature of the material body, suggesting that bodily practices, lodged in the habitus, mediate between the individual person and his or her society’.

As entrepreneurship is a significantly social practice (Cope, Jack, & Rose, 2007; Thompson, Verduijn, & Gartner, 2020, pp. 248–250), we argue that entrepreneurial growth perceptions are part of, and a product of the social environment, the habitus of which the entrepreneur is part, as well as a result of the social and other practices involved in being entrepreneurial. This in turn implies that the entrepreneurial environment is key to entrepreneurial growth perceptions: entrepreneurs' participation in their networks helps them to develop and mould the contours of their perception of entrepreneurial growth and the type of growth that they strive for.

We also find value in the way in which the habitus has strong psycho-social dimensions in the sense of the mutual constitution of the individual and the social relations within which they are enmeshed (Reay, 2015, p. 1). Whereas Reay (2015) points to the interactions of the affective aspects of personal history with the processes that maintain and reproduce social structure, here, we focus more on positive affect as a motivating, engaging aspect of entrepreneurial activity, specifically in relation to friends, family ties and the satisfaction of one's economic life being in alignment with one's self and motivations. This attention to social context and to well-being also help to explain the role of affect and passion in entrepreneurial settings (Cardon, Glauser, & Murnieks, 2017), as well as intrinsic satisfaction and pleasure in entrepreneurial activity.

2.3.3 Practice

Bourdieu's concept of Practice in the broad sense (as compared with a specific practice) denotes routinised behaviour composed of elements that include physical, cognitive, knowledge, affect and motivation-related aspects (Reckwitz, 2002). The term is thus integrated and composite and inherently holistic in contrast to contemporary psychological analytical constructs that decompose behaviour and examine the structural relationships between its constituent elements. A growing body of work views market activity from practice perspectives (Røpke, 2009; Schatzki, 2005). Practice theorists share Granovetter's (1985) view of market activity as socially embedded, but focus more specifically on the ways in which it is constituted by the interaction of practices and material context. They also view the individual and the social as closely entwined, mirroring and reproducing one another (Schatzki, 2005). Moreover, practice theory being a form of cultural theory (Reckwitz, 2002), stable social practices are seen as the outcome of symbolic structures of meaning and knowledge. This aspect is particularly relevant to entrepreneurship, given the many practices that entrepreneurs must learn and enact, consciously and unconsciously, in order to create and develop their ventures and specifically their use of symbolic appeal in persuading, co-opting, garnering support and (of course) in selling and exchanging goods and services. While these might appear as idiosyncratic, self-directed acts, practice theory suggests that they are shaped by the nature of their coupling to the environment (i.e., the everyday structures and the entrepreneurs' sense-making of those structures). Such an approach acknowledges the role of context in three ways. Firstly, it ‘pays explicit attention to social and cultural context’ as integral to entrepreneurial process, and secondly, in epistemological terms, ‘it is grounded more deeply in the context of the social and human sciences’ (Hjorth & Johannisson, 2008, p. 82; Anderson, Dodd, & Jack, 2010) and third, context as allowing affect, values and feelings to be expressed at the workplace and in and through a venture (e.g., Härtel, Zerbe, & Ashkanasy, 2005).

2.3.4 Social capital

As Gedajlovic, Honig, Moore, Payne, and Wright (2013) note, scholars have increasingly recognised that entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship are socially situated and that the social environment is crucial for opportunity discovery, evaluation and exploitation. Bourdieu's social capital theory has been acknowledged for having significant explanatory power, helping to explain processes and outcomes of social interactions at multiple levels of analysis and across diverse situations and contexts (Anderson & Jack, 2002; De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; Gedajlovic, Honig, Moore, Payne, & Wright, 2013; Klapper, 2011). As Portes (1998) observes, Bourdieu probably supplied the first systematic and potentially most refined analysis of social capital, which he defined as, ‘the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition’ (Bourdieu, 1986, p. 248). Bourdieu linked five aspects together: resources, networks, institutions and relationships and mutual recognition. He later modified this version and added two ideas, that is, that social capital exists both at individual or group level and that it has an important role to play in the different structure and dynamics of societies (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992; Klapper, 2011).

The central proposition of social capital theory is that networks of relationships are a valuable resource for conducting social affairs and that social capital is both the origin and the expression of successful interactions (Anderson & Jack, 2002). These relationships provide the members with ‘the collectivity-owned capital’ that entitles them to credit (Bourdieu, 1986). Much of this capital lies in networks of mutual acquaintance and recognition. With reference to Powell and Smith Doerr (1994), Anderson and Jack (2002) describe social capital as both the ‘glue’ that binds to create a network and also the ‘lubricant’ that eases and energises network interactions. Consequently, analysts of social capital are generally concerned with the importance of relationships as a resource for social action (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). This is also consistent with Granovetter's (1985) emphasis on the social embeddedness of economic activity, a perspective that views the entrepreneur as the one who develops social capital through networks which will then provide access to information, support finance, expertise and allow ‘mutual learning and boundary crossing’ (Cope, Jack, & Rose, 2007, p. 214).

Our empirical study combines these elements of Bourdieusian thought, which appear to correspond well to growth as a subjectively experienced and lived practice, with the previously discussed insights from Shotter's ‘withness’ thinking.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The hermeneutic research design is central to the premise of the paper. Rather than classify forms of entrepreneurship on the basis of externally observed characteristics, we want to start from entrepreneurial practitioners' understandings of entrepreneurship and specifically understandings of growth. In this, we follow Anderson, Dodd, and Jack (2010) and their application of Heidegger (1927, 1962), who advocates that to enter the hermeneutic circle, one must become a member of the shared world one is investigating. To this end, the lead researcher was embedded as an academic in a Finnish higher education institution, snowballing entrepreneurial contacts via scoping surveys, a roundtable and semistructured interviews, exploring growth perceptions without a priori considerations. Only latterly and retroductively were Bourdieusian concepts applied to help explain the observations.

Ontologically, the paper belongs in the phenomenological tradition of entrepreneurship study. Phenomenological inquiry, following Cope (2005) offers richness and depth to interpretative engagements with entrepreneurship. As Warren (2004) points out, more recently entrepreneurship and small business management research have understood the value of interpretive social science, which has led to a growing shift away from researching the entrepreneur simply as a unit of economic activity or as an ‘entity’ with implicit personality traits (Warren, 2004, p. 7). Viewing entrepreneurship as a complex, dynamic, lived experience subject (Cope & Watts, 2000) justifies methodologies that differ from the often reductionist perspectives that are used in entrepreneurship research (Champenois, Lefebvre, & Ronteau, 2020; Skaveniti & Steyaert, 2020). As Wittgenstein (1969, p. 18) suggests, those who ‘constantly see the method of science before their eyes, and are irresistibly tempted to ask and answer questions in the way science does’ neglect the essence of the concept under investigation, in our case here, entrepreneurial growth. Drawing on Gadamer (2000), we acknowledge that the subject acquires its life only from the circumstances in which it is presented to us and ‘presents different aspects of itself at different times or from different standpoints’ (Gadamer, 2000, p. 284).

From this perspective, the narratives, discourse and subjective experience of entrepreneurs matter (Anderson, Dodd, & Jack, 2010; Cope & Watts, 2000; Rae, 2000) and can help to create a more embedded, integrated and realistic, practitioner-based understanding of growth perceptions. Following Gadamer (2000) and Shotter (2017), we conclude that in its essence, the concept of entrepreneurial growth ‘is not something that already lies open to view and that becomes surveyable by a rearrangement, but something that lies beneath the surface’ (Shotter, 2017, p. 9). By creating a research design consisting of two interlinked research phases, the primary objective was ‘coming to an understanding’ of the situation from within a ‘dialogically-structured developmental process’ (Shotter, 2017, p. 9). This meant involving entrepreneurs in several methodological tools of investigation, with one of the researchers being part of the academic circle with whom the Finnish entrepreneurs engaged.

The research design comprised two linked phases: exploratory and main. Following Anderson, Dodd, and Jack (2010) and Alvesson and Sköldberg (2009), we then worked abductively to apply the concepts of habitus, practice and social capital in this context, moving between empirical findings and conceptual developments in a reflexive spiral. The purpose of this dialogic approach is to generate findings that are informed by prior theoretical understandings, while also allowing for the emergence of novel insights from the practitioners.

3.1 Exploratory phase

Our aim in this phase was to lay the ground for subsequent dialogue between the researcher and the researched by eliciting key themes and issues, while also drawing in potential participants for in-depth, follow-up interviews, as well as participants for a round table as part of the MBA programme in the main investigative phase. We adopted an e-postcard survey, following Thorpe, Gold, Holt, and Clark (2006). The latter, conscious of entrepreneurs being short of time, sought a method of enquiry suitable for busy, hard to reach individuals. Following the same approach, here we used a small e-postcard on which was printed a picture of a ‘staircase to heaven’ as a visual hook. The picture was intended to summarily express the idea of a growth journey, while leaving space for a response to definitional questions regarding the meaning of growth, innovation and creativity. The asynchronous nature of email, relative to interviews, is considered to have the advantage of assisting reflexivity, in that it provided the opportunity for reflection and editing of responses by the entrepreneurs (Thorpe, Gold, Holt, & Clark, 2006).

The e-postcards were first distributed face to face to MBA alumni of the Finnish university, most of whom had an entrepreneurial background, generating 35 valid responses. This was followed by a LinkedIn survey using the same e-postcard format to a varied group of Finnish entrepreneurs associated with the university, which provided an additional 20 responses. The elicitation questions (appended) comprised a series of questions relating to the entrepreneur's background/contact details as well as their perception of growth, innovation, creativity and out of the box thinking.

At this stage of the investigation, an overview of growth perceptions was sought, which was then later explored in greater depth through the roundtable and semistructured interviews. Data collection and analysis in this phase were treated as interrelated processes (Miles & Huberman, 1994) involving a mix of strategies such as pattern seeking, clustering and the use of organising matrices to assist with both (Ghauri, 2004). The exploratory work gave rise to themes that were then pursued in the interviews; the results of which together led us to work with Bourdieu's concepts as an analytic frame. The results of both surveys are shown in Figures A1 and A2, which summarise the findings of the e-postcard surveys.

3.2 Main investigative phase

Responses to the exploratory stage provided a set of themes and issues to explore further in the second stage and also—it was found subsequently—acted as corroboration of themes that were prominent in the interviews. This consisted of (a) a roundtable with six Finnish entrepreneurs, focusing on entrepreneurial growth; (b) seven semistructured interviews, follow ups with the roundtable participants (six) and one additional interview with a cofounder. The questions for both roundtable and semistructured interviews are appended. All of the individuals engaged and contacted constitute a convenience sample of entrepreneurial contacts known to the university. We do not claim and did not seek representativeness with respect to the wider population of Finnish or non-Finnish microentrepreneurs, 1 but rather illustrate empirically. Permission for use of transcribed data for research purposes was gained from the participants. The lead researcher conducted the roundtable and the semistructured interviews in English. The conversational dialogue style roundtable typically covered the origins of the business, its history, growth perceptions and business practices. Choosing this approach brought unanticipated narratives that led to deep and different understandings and meanings (Trahar, 2009). Roundtable conversations and interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed. Table A1 summarises the characteristics of those whose views are used below for illustrative purposes.

3.3 Data analysis

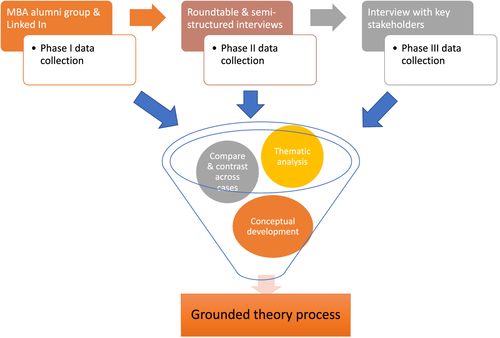

Phase 2 involved two researchers and two approaches. One of the researchers conducted a line by line analysis of the transcribed data manually, while the second researcher coded the same data in Atlas.ti, enabling additional qualitative analysis. In both approaches, the stages of data analysis went from sifting the data, iterative readings and reflections, emergence of categories and concepts, to consolidations of categories and concepts and framework development. The sifting process (stage 1) involved discarding whatever seemed irrelevant and bringing together what appeared most important (Eisenhardt, 1989); in stage 2, the researchers were looking for patterns (Halinen & Törnroos, 2005); in stage 3, categories and concepts emerged within the research notes and based on the transcripts. The constant comparative method (Anderson & Jack, 2015; Glaser & Strauss, 1967) was the dominant design approach at this stage, and the qualitative software analysis tool Atlas.ti was used to support thematic analysis and compare findings. In stage 4, categories and concepts were consolidated, and in stage 5, the researchers continued to develop a framework driven by the comparison with theory, leading to further fine-tuning of categories and concepts. Figure 1 summarises the research design.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Exploratory phase

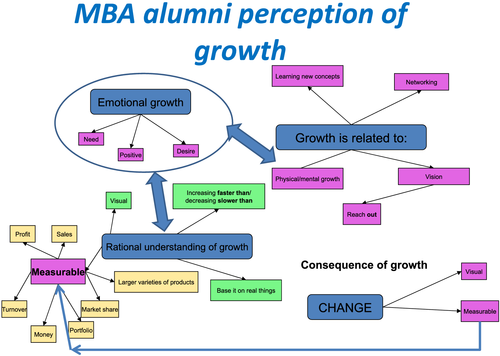

Figures A1 and A2 summarise the themes found in the exploratory survey work: Figure A1 describes the themes of the MBA e-postcard survey results, and in Figure A2, the results from the LinkedIn group. For the MBA respondents, many of whom were also entrepreneurs, growth was perceived as a thoroughly multidimensional, multiconnected concept. The entrepreneurs view growth holistically, as not only including both quantitative, measurable conceptions such as profit, sales, turnover, money, portfolio, market share and product range but also themes of personal growth, involving emotions, personal development, learning, having a vision and growth through relationships. Arguably, these conceptions of growth are connected with the participants' habitus, practices and social capital. Whereas these conceptions of growth help to form a holistic understanding of growth seen through the practitioners' eyes, the elements were not necessarily perceived as integrated and mutually consistent. Others have previously raised the question as to the extent to which entrepreneurs achieve a balance between potentially opposing imperatives (Achtenhagen, Naldi, & Melin, 2010; Thorpe, Gold, Holt, & Clark, 2006). This theme was later picked up in the individual interviews.

The e-postcard survey of the LinkedIn entrepreneur group gave similar results to the above, with similar themes and discourses, but some additional insights. Notably, some of the LinkedIn group critiqued the idea of growth per se, using terms such as ‘greed’, ‘black and white thinking’ and the idea of excess or ‘too much’. Growth was seen as a secondary objective, necessary only for maintaining living and welfare standards, particularly in relation to the family. Long-term growth was preferred. Growth was also suggested as something culturally defined and questions were raised as to whether growth was an obligation at all. We see here perceptions of growth which (a) are holistic in the sense of having both quantitative and qualitative dimensions, (b) emerge out of everyday practice in a particular habitus, (c) critique and question the dominant growth thinking and (d) prioritise well-being and personal development. This juxtaposition of potentially opposing ambitions creates not only a picture of potentially complementary but also conflicting perceptions of growth, and the discussion of the interview data aims to shed further light on this. Yet what we see here already is that quantitative and qualitative aspects of growth, as well as a critical view of growth, were suggested by the entrepreneurial practitioners as key to their growth understanding, with limited priming from the lead researcher, indicating an internalisation of multifaceted views of growth and experiences of growth practices in and underpinning the entrepreneurial persona.

4.2 Main investigative phase

Building on this exploratory phase, the semistructured interview questions and roundtable were designed so as to continue to probe growth perceptions, giving rise to themes that emphasise growth as personally and socially contextualised. The experience of, and associations with, growth are intimately connected with—and expressed through—specific practices, motivated by and reflecting each individual's habitus, including their own emotional disposition, experience and history. Throughout, social and emotional life matter greatly to the individuals questioned, not in a way that is incidental to their business, but integral to it.

In the sections below, we describe six notable themes, illustrated with extracts from the round-table and interviews, and demonstrating how they can be interpreted via selected Bourdieusian concepts. For the interviewees (for whom we use pseudonyms), growth is a multiperspectival concept in the sense of a phenomenon presenting different aspects of itself at different times and/or from different standpoints (Shotter, 2017). The ensuing sections shed light on these different dimensions.

4.2.1 Growth as striving for balance between personal and business

A person's habitus is both individual and social. As such, it is highly differentiated across individuals, reflecting personal dispositions and experiences, as well as the structures into which individuals are born and have lived. Nonetheless, what emerged strongly as a theme common across the individual entrepreneurs is that growth has two faces for them: on the one hand, they shared the notion of growth as something quantitative: numerical growth, specifically in turnover and staff numbers. On the other hand, it is something personal, intimately connected to their life. We also find a very strong association between the personal growth of the entrepreneur and the growth of their enterprise.

Entrepreneur Hannes, for example, works in the media industry creating music videos and commercials. He explains his understanding of growth as follows: ‘I would divide growth into two types. The first is about soft values (i.e., what I want to do in my life and how my perspective is growing with the business). The other one is how to measure growth in numbers. Let's say this year we are looking for 300% growth compared to last year. So this is about finance, number of employees’. Hannes clearly points out the complementarity of his views on growth: on the one hand, it is about the qualitative side of his life, the soft factors and how he changes through the business; on the other hand it is about the quantitative side, the numbers. Growth is part of a wider vision for the entrepreneurs. Andrew is a CEO of an international bookstore: ‘Growth keeps this business interesting’, he says. His views clearly emphasise that the quantitative side is not a driver for him. In fact, the more emotional undertones, expressing pride in the quality they sell, but also the aspect of novelty is what makes this interesting for him.

Similarly, for Walter, growth is about achieving balance between targets and the more intimate, personal side of growth: ‘… I don't think about growth. I think about targets though, a certain level of business I want to achieve in terms of numbers of customers, numbers of companies I want to scale up. At the same time growth is very personal to me. I learn and understand the game and the rules of the game. There are things which are not in the rule book depending on your own personal core’. When asked for his definition of growth Walter immediately retorts: ‘What type of growth, personal growth?’ Walter's comments make it clear that he does not pursue growth simply per se: growth is emergent from his pursuit of practices enacted in response to the challenge to learn the rules of the game, a metaphor that he introduces. His entrepreneurship practice seems to him like a chess game in which he is learning to make the right moves to be in or even ahead of the game.

What emerges is that growth is something more comprehensive, something more personal to these entrepreneurs, not just numbers as Matti (a serial entrepreneur) recognised; yet there is a need to communicate growth in numbers. Growth needs labelling as he suggests, labels are necessary to communicate to, and with an audience:

‘… obviously this is financial growth, in a way, it's like any other labelling things, you need to label things to communicate and financials are the easiest way to communicate growth and success’.

Similarly, Mohammed emphasised: ‘The company is my life, my dream. I would like to be the company … the company is … not to be alone. The company means productivity also, my philosophy. I like productivity numbers, it should bring numbers. As a mortal person I also like to see numbers. To have a nice car, nice clothes, a nice tie, go for a nice honeymoon, like that and also develop other people’.

Growth is thus also experienced in terms of its outcomes and is both business, personal and individual experiences. In this regard, growth is an experience, the nature of which varies according to habitus and consequent social experience. For Andrew, there is also a role for intuition: ‘I really trust my feeling, mine and my associate's feelings, and I use them to establish market needs’.

These statements also suggest that the entrepreneurs themselves strongly influence the type of growth that they enact and experience, as they strive for a balance between different imperatives, personal and organisational. They are themselves embodying their growth perceptions.

4.2.2 Growth through social capital that is ‘natural’

For our interviewees, use of social capital is experienced as a ‘natural process’, a connection with friends and associates, rather than a deliberate, instrumental cultivation and use of contacts. This practice is explicitly described not as one of networking, nor as one of a reciprocal trade or exchange. Here, the concept of habitus is particularly relevant: Bourdieu used the term as shorthand for the sum of cultural resources that a person has available to them as a result of their social position and experience—hence, an endowment that differs between individuals. Here, we see individuals drawing on their habitus and their affective ties routinely as part of their business development. Their naturally acquired contacts are useful in a business context, but have not been sought for that reason: ‘This is a small town and it happens to be the capital, so basically you grow up with people who become the people who do different kinds of things’ (Michael).

Networking is part of their natural entrepreneurial habitus and part of everyday practices. The roots of these entrepreneurs are in Helsinki and this creates familiarity with their environment. As Michael describes it: ‘I have never been a very big enthusiast of networks. It's because I've been networking all my life without any active participation …’ Michael also says: ‘… that's like one of our big advantages that we are very well connected, so to say. I mean, I don't know the correct word but I kind of despise, look down on people who are so big about networking. It's just that we have a big, a huge amount of friends basically. It's not like I would ever go out and say let's go networking, I would never do that, I hate all these networking events, it is so superficial’. Rather Michael has long-standing relationships with people in the same region and the act of growing up together—which suggests a sharing of experiences—is an important part of his habitus and also indirectly influences his practices.

Thomas also commented on the close relationship between business and friendship ties: ‘But … I would say that, you know, these contacts and the friends come close very much hand in hand’.

Mohammed also underlined the importance of his family, here in particular his wife for developing the business and the inseparable social and business spheres and ties: ‘All the books I have in my business library, she bought them. If you think about it, it's like that. Everybody, including her, I include in the business. I give them the opportunity to do something, the family and the friends everywhere. I'm working all my life. I don't have time for socializing, it is an enjoyable life. I can't separate them…Yes, all the social and work in the same box. Not easy, but enjoyable. There's no time’.

This overlap of social and economic has, as we can see here, pragmatic reasons as there is little time to separate these.

4.2.3 Growth and ecological and societal concern

The entrepreneurs in this study also recognised that entrepreneurial growth is interconnected with ecological and societal issues, as well as a quest for generating better quality. Andrew, a serial entrepreneur, had most recently gone into restaurant businesses and recognised that they could use their purchasing power to put pressure on suppliers to change their practices:

‘We do have some ecological ideas behind this … Now we have worked together with WWF, we are trying to follow their guidelines. Now we are putting extra pressure on the fish import trade. They need to change their business because they don't want to lose us. So that way we are in the position to change things around there. And our customers really respect that. It's not like, it harms if we don't sell such products that our competitors do. We are saying no to tuna fish. We already don't have tuna in our set menus, so people need to order it if they want to have it, but in two weeks, or after summer we don't accept tuna anymore’.

As Matti underlined: ‘I mean, 90% of the best business decision we make, or even in 100% of the business decisions that we make, we keep the human aspects involved, it's really something that will enhance business models in the way of life. It's something that we really want to do with our lives and of course having that involved, makes us very enthusiastic at our work. We don't do anything that we don't feel totally comfortable with, although there might be some financial profits available, if it's something that we would not 100% enjoy, we won't do it. Because I believe that it wouldn't be good enough, in that case’.

4.2.4 Growth as learning

The entrepreneurs live and enact the growth of their businesses, yet there is a process of learning that accompanies such growth, which encompasses themselves and those working with them. As they learn, their business—which is part of their identity—also learns, and this impacts their lives and significant others' lives. They speak as much about others as themselves when talking about the relationship between learning and growth.

Andrew viewed growth as closely related to the process of learning: ‘My definition of growth is about learning. So, if we don't grow, it means that we didn't learn anything this year, anything compared with last year. And if we grow fast, it means that we have learned a lot. Because the customers are there, products are there, it's just we know how to spread it out. If we can't do it better than before then we have done something wrong. So, for me, growth is this’.

Similarly, Mohammed emphasised that the development of his company was primarily related to his own personal development, his own learning: ‘It started in the depth of the subject and it was for my personal development’. Asking him why he wanted to grow, he responded: ‘I don't really have a desire to grow, actually. However, for me … life is about growing and growing is about life. Growth is not a choice, but growth is an effect. If you don't grow you feel abnormal. The meaning of life for me is to be in continuous change’.

4.2.5 Growth as a collective experience

In addition to this connection between entrepreneurial learning and growing of the individual, we found that these lived experiences of growth were closely related to the entrepreneurs' interest in developing and inspiring others. For Andrew, growth comes about through his staff developing their skills and themselves growing, opening them up to new challenges and new job opportunities within the group: ‘So, that's, that's a nice way to grow, actually, because first, you get to know the people, and they do only a few hours every now and then, because they have school, and then you help to build up their career and teach them and then, one day when they graduate, if you're lucky they will stay with your company’.

Staff benefits from personal growth by acquiring new skills and building their career, but the venture also gains in terms of its capacity for innovation and increased stability, as staff may feel encouraged to stay with the business for extended periods. Passing on knowledge, educating these young people and helping them build their career are part and parcel of Andrew's personal growth conception. This is an interesting example of where individual entrepreneurial growth and organisational growth stretch beyond their boundaries to affect the growth of others, here future generations of employees. It is also noteworthy that Andrew feels ‘lucky’ if these young people stay in the business, which is quite a humble view of the situation. More specifically, these insights suggest a collective nature of the growth process.

Indeed, Mohammed was critical of corporate disregard for individual employees: ‘You look at the world today and work is part of your personal identity. However, you are not the system of a company … the company earns more, they earn more than you do and they kick you out if you have a problem. But in a different way, in a different procedure book, you build the organization for the people. And they own this place together. This is re-organizational thinking based on a passion. That is your passion, that's my passion, that's my feelings’.

Likewise, Matti emphasised the notion of growth, generating well-being for everybody in the venture, with everybody pulling in the same direction:

‘In the next 12 months I would like to grow our company. I would like to feel that I don't want to be the only person who has a condo, because I really need help, I would like to introduce people. I don't have to fight for my opinion, we have the same opinion and we have the same strength, we grow this company together’. Asked whether this meant that he wanted to work more collaboratively, he answers using metaphors: ‘More partnerships. And more horsepower, horses running in the same direction. I can't change my dream but I would like to find a horse, no problem. Enjoying horses in company. If I am in my dream alone … I can give up a little bit from my dreams, but being alone, is not a good place to be’.

Growth is here a collective experience, growth is here about people, about owning and sharing together, about learning together, based on emotions, here passion for what you do. Horses running in the same direction, led by a dream. The idea of passion that characterises the collective spirit is closely linked to emotions as illustrated in the next section. A commitment to different collective groups was also expressed in terms of reaching out and networking in the MBA e-postcard survey and as family welfare and customer well-being in the LinkedIn survey.

4.2.6 Growth driven by emotions: Love, passion and values

All of the entrepreneurs referred to affective experience and motivation in relation to their subjective experience of growth. For example, in the MBA e-postcard survey results, reference to emotional growth was notable, while in the LinkedIn survey, normatively connected emotions were expressed in ideas of greed, ‘black and white’ thinking, and growth being about excess.

Each experience of growth and emotion was personal to the acquired dispositions of their own habitus: Mohammed was particularly explicit: ‘The ultimate goal is to love, love the people, the customers with whom you exchange. Marketing is about love, loving your products, loving your customers … For me, work and emotions are in one basket. I am an emotional person but I also like to see numbers at the end of the day to develop other people. You are the company and the company is me. The company is my life and my dream. Love is the key, love for my wife, for the company and for other people. You cannot dissociate emotions and business’. Andrew expressed similar views: ‘And in the morning I start with my work. I was working around the clock and I was happy. Not tired. It is ok like that. It's amazing power’.

Conversely, Michael highlighted more challenging aspects of entrepreneurial growth, again experienced personally and reflecting his own dispositions. With his friend he had acquired a bar in the centre of Helsinki, which was a good investment: ‘But there was a problem: the more we intoxicated our customers, the more we did succeed financially, however, that was kind of a moral problem at some point, illegal as well. You are not allowed to sell to people who are drunk, with a drinks bar this might be a problem’. In addition to ethical concerns, Michael also felt out of his depth behind the bar, and together, this led him to conclude that at times he even hated it. As Rosaldo (1984) suggests, ‘emotions are embodied thoughts’; here, our entrepreneurs embody a range of feelings ranging from love to hatred in their ventures, and they live out, experience these feelings on a daily basis.

5 DISCUSSION

Our premise has been that, rather than categorising forms of entrepreneurship according to externally derived attributes based on identity and difference, we can also learn about those forms of entrepreneurship by looking from within. Direct observation and to a certain extent direct participation in the field as part of practice theory made it possible to explore and describe important features of the entrepreneurial growth phenomenon (Nicolini, 2012). What emerges from the foregoing is a picture of entrepreneurial growth as embodied and enacted by the entrepreneur, who acts as the ‘carrier’ of a practice (Gartner, Stam, Thompson, & Verduyn, 2016) as situated in a certain habitus, here shaped by the Finnish context, where social capital is built up over time, critically supporting the entrepreneurial venture, and where practices that are characterised by the pursuit of personal values in terms of the environment, social equity and quality of products are propelled by passion and love for those practices, in addition to their more instrumental outcomes.

Furthermore, growth is viewed and lived as a collective activity, involving stakeholders ranging from family, friends to employees, for the benefits of not only the entrepreneur but also those others, all connected by social ties of one form or another. This collective dimension seems to respond to social and emotional needs of the individual and the organisation. Looking for theory that helps to explain this integrated, embedded picture, we find Bourdieu's concepts—and the practice turn in entrepreneurship studies more generally—helpful for its own premise that economic and social life are, in many ways, inseparable.

We would not argue that our illustrative group of Finnish entrepreneurs practise ‘sustainable entrepreneurship’ in either a conscious sense, or that their ventures would be recognised as such in terms of predefined criteria relating to business objectives or models. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that there are likely to be underlying commonalities in how entrepreneurship is enacted by those normally identified as ‘sustainable entrepreneurs’ and their more conventional counterparts. In some respects, this is unsurprising: the problems of categorisation have been well-rehearsed, and some degree of isomorphism is to be expected when businesses often operate in similar institutional contexts. However, in the past, these commonalities have often been obscured, limiting our understanding of key issues, including perceptions of entrepreneurial growth. Our study suggests that these hidden features are most richly revealed by taking an insiders' view: Shotter's ‘withness’ thinking proved to be a suitable methodological vehicle and—with its emphasis on socio-economic entanglement—Bourdieu's critical social theory provided terms of analysis that helped to explain what we found.

5.1 The theme of collectivity

Sustainability discourse emphasises our collective fate, the need for collective solutions and so on. It appeals to concern for others now and in the future. One of the strong themes that emerges from the data analysis is a collective approach to growth. Arguably this resembles Buber's (1970) connected ‘I-Thou’ relationship, with an emphasis on the collective (a feature that does seem more prevalent in Finnish culture than in more individualised market societies). 2 The results show an emphasis on both the entrepreneur as an individual and their human collective, rather than a purely, reductionist understanding of entrepreneurship as business. This reasoning is intimately related to the need for the entrepreneur to find balance between individual and organisational growth, individual and organisational learning, individual and organisational values. The entrepreneur's connection with the collectivity also means that their ambitions to grow are oriented towards creating well-being in themselves and their family, their staff (present and future), their customers through their products, their community and even their country, which suggests a holistic understanding of growth thinking.

The notion of collectivity is also theoretically close to Bourdieu's habitus where growth is habitually and socially situated. Growth happens in a context, here Finland, in collaboration with others, whether these are family members, employees, customers or other stakeholders, and it is a collective experience of those involved, and it serves a collectivity. The idea of well-being that these entrepreneurs are pursuing for themselves, their staff and communities further resonates with the Sustainable Development Goals for Health and Well-being, Decent Work and Economic Work and Sustainable Cities and Communities, which though gaining in recognition, are still under researched in relation to business organisations and sustainable entrepreneurship more specifically (e.g., WBCSD, 2020).

For these entrepreneurs, growth is not just an individual experience, but is experienced as part of social and emotional lives embedded in their Finnish habitus. Individual growth is aligned with that of others, so growth becomes a collective experience, generating well-being for the individual, the family, the region and the country. This collective experience informs practices and behaviours in a certain habitus that is conducive to such experiences. This is in line with Champenois, Lefebvre, and Ronteau (2020) who highlight that practice theories are fundamentally relational in contrast to the cognitivist, rationalist perspective of western tradition and its disconnected logic of scientific rationality. One might rightly ask how this could be otherwise, but this would be to miss our point. While it may seem self-evident that growth is experienced in this way, it is generally researched and thought about using methods and concepts that abstract from its context and from the emotions of those involved, while also paying insufficient attention to growth as a collective endeavour.

The notion of ‘collective growth’ is also reminiscent of Tönnies and his terms Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft as complementary analytical categories (Waters, 2016). Tönnies contrasted an older traditional Gemeinschaft world, where relationships emerged out of social interactions of a personal nature and personal emotional attachments such as loyalty, with Gesellschaft societies. In the latter, interactions were based on more ‘rational’, impersonal relationships mediated by money, wages and calculated value relationships leading to individual advantage. The basis for the latter was according to Tönnies ‘rational will’ which he contrasts with the ‘natural will’ as practised in the Gemeinschaft (Waters, 2016). Tönnies ‘natural will’ resonates with the finding here that social capital that is ‘natural’ to the entrepreneur is key to the venture and to the collective growth experienced. The notion of ‘rational will’ finds very strong resonance in the MBA survey results and in the conversations with the entrepreneurs where participants associated growth with a rational understanding of growth involving profit, turnover, product portfolios, that is the very traditional understanding of growth. However, as one of the entrepreneurs in the study mentions in a later interview, these are just labels to communicate to different stakeholders, hence necessary but only one facet of growth. Labels suggest that there is certain language that these entrepreneurs have to speak to communicate with different stakeholders, yet we show that growth means much more when explored further.

5.2 Growth practices driven by emotions and passion

In recent years, the idea of humane entrepreneurship has been posited, embodying the values of empathy, equity, empowerment and enablement (e.g., Kim, Eltarabishy, & Bae, 2018). These values are consistent with those of the entrepreneurs studied here, who anchor their thinking about growth in the drive to learn, feel and engage with their ‘natural social capital’. The study has shown that entrepreneurs' perspectives are motivated by a variety of nonmaterial factors that have direct implications for enhancing the sustainability of entrepreneurial growth practices, including their embeddedness in a collective habitus and the perceived need to achieve a form of well-being for themselves, their families and the surrounding collectivity. These findings also throw some light on the role of affectivity in practice theory, including the ‘teleoaffective’ structures, which connect a person's orientation towards particular goals and ends, such as growing a business (i.e., teleology) with their emotions and motivational engagements (i.e., affect) (Champenois, Lefebvre, & Ronteau, 2020; Schatzki, 2005; Welch, 2020).

6 CONCLUSIONS

Our study supports the view that, although superficially attractive, categorical and dichotomous distinctions between ‘sustainable’ and ‘conventional’ entrepreneurship inevitably oversimplify their subjects and mask some important commonalities (Thompson, Kiefer, & York, 2011; Outsios & Kittler, 2018). Participants in this research understand their entrepreneurial growth path emerging as the result of a long learning experience that goes beyond the constraints of profit/nonprofit attitudes to combine emotional and ethical well-being with commercially oriented goals. We have addressed a relatively underresearched aspect of sustainable entrepreneurship by probing practitioners' perceptions and experiences of firm-level growth using a methodology that responds to the call for more practice-based approaches in entrepreneurship (Champenois, Lefebvre, & Ronteau, 2020; Skaveniti & Steyaert, 2020). In doing so, our study has revealed a broader and more holistic view of growth, which embraces multiple forms of social value creation, including emphasis on the collective nature of growth benefiting the entrepreneur, family, and the wider collectivity, the need to strike a balance for growth between the individual and the organisation, the role of emotions in and as part of the growth process. All of these aspects are key to and arise from the entrepreneurial habitus in which the entrepreneur and his business are embedded, in addition to the pursuit of economic outcomes (Korsgaard & Anderson, 2011).

In this study, we see how entrepreneurs engage in learning about growth and how they are guided by a mixture of positive and negative emotions in pursuing their growth-related efforts. Such learning accompanies the process of embodied and enacted entrepreneurial growth where knowledge is incorporated not just by the material body but by a being comprising mind, body and environment (Gieser, 2008; Shotter & Tsoukas, 2014). We provide a subjectively experienced portrait of growth, presented in the Bourdieusian terms of social capital, habitus and practice, that we find corresponds well to growth as experienced, lived practice, with tones that include not only the economic, environmental, social and ethical but also the personal, the affective, aspects that make growth a human experience.

We have drawn on insights from Shotter's ‘withness’ thinking, in conjunction with a Bourdieusian perspective on growth as practice and as an outcome of habitus. While the empirical findings are not readily generalisable beyond this setting, we can point to several implications of the approach for future research, policy and practice in the field of sustainable entrepreneurship.

6.1 Implications for research

First, we have sought to add to the practice turn in entrepreneurship research (Champenois, Lefebvre, & Ronteau, 2020; Skaveniti & Steyaert, 2020; Thompson, Verduijn, & Gartner, 2020) not only by re-emphasising the roles of habitus and social capital but also by showing how Shotter's withness thinking can underpin research of entrepreneurial perceptions of growth ‘from the inside’. The role of social capital has been widely acknowledged, but much less attention has been paid to habitus, and even less to the affective dimensions of the personal dispositions that Bourdieu locates therein. These perspectives have a particular relevance to research on sustainable entrepreneurship, and to the broader, but closely aligned, domain of purpose-driven entrepreneurship (Muñoz & Cohen, 2018, p. 317; Skaveniti & Steyaert, 2020). 3

Secondly, the findings reinforce previous studies in finding that that firm-level growth, as the outcome of practices, is a highly situated process that cannot be reduced to any one of its constituent elements (Thompson, Verduijn, & Gartner, 2020, pp. 247–250). Furthermore, the perceptions of growth exhibited in our study suggest that differences between sustainable entrepreneurship and more conventional forms are more nuanced than is commonly appreciated. The term ‘purpose-driven’ entrepreneurship lacks sufficient capacity to distinguish, when conventional entrepreneurs too are impassioned for their venture and for others through their venture. While this blurring of the boundaries may pose challenges for those seeking a simple definition of sustainable entrepreneurship (Muñoz & Cohen, 2018), it can also be interpreted as a hopeful sign that there is scope for a substantial upscaling of sustainable entrepreneurship in the wider small firm population, given supportive institutional conditions. The entrepreneurs in this study make sense of themselves as multifaceted persons embedded in a collectivity and pursuing a venture (or an adventure), of which growth is an intimate part, not just an outcome. Moreover, not all of our entrepreneurs sought growth—echoing the steady state economics, recognition of limits to growth and doughnut economics that we began with.

Thirdly, in terms of future research, replication at larger scales, within different cultural contexts and different types of entrepreneurship would be illuminating. While we think our main points and approach are generally applicable, it remains an open question as to the extent to which our group of entrepreneurs are typical nationally and internationally. A further area to explore is the connection with conceptions of degrowth: the socialised view of growth found here echoes wider debates in sustainability discourse, with its longstanding critiques of how markets neglect the social, the environmental and ethical dimensions of growth. The relationship between the human and the market—in addition to a dependence on context—have been discussed by contemporary, bounded market advocates such as Latouche (2003). Dialogue with different types of entrepreneurs, for insiders' views on degrowth options, would also be fruitful.

6.2 Implications for policy and practice

In terms of implications for policy, we suggest firstly that subjective experience of growth needs accounting for in policy support measures; secondly, that this entails not only attention to process per se but also to several specific features of that experience. In particular, the role of individual habitus (past history, skills, dispositions, associated values) and acquired ‘natural’ social capital in shaping entrepreneurial practice need consideration. From a policy intervention perspective, this in turn implies a need not only to consider how individuals might be assisted in building up the skills, attributes, social capital required but also to develop the mindset for sustainable entrepreneurship in particular. However, it also implies a need to attend to the policy context, as a key feature of the socio-material context in which entrepreneurs operate. Without institutionalised incentives to shift towards sustainability, Bourdieu's characterisation of agency and structure implies that such a shift is unlikely.

If entrepreneurial growth is experienced in terms of economic, social, cognitive and affective that are intertwined at individual and social levels and manifested in particular practices, this begs the question of how to support change in an integrated way. We suggest that it firstly implies a need for encouraging reflexivity on the part of the nascent entrepreneur: attention to themselves, their motivation and ambition, their social capital and not only how all might be enhanced in ways conducive to both their own growth, the growth of their enterprises, but also of how it contributes to the growth of the collectivity. For example, social network analysis of oneself would usefully benefit the more conventional exercise of business planning offered at undergraduate and postgraduate level. This can be expected to raise awareness of the role of social capital at the start-up and throughout the different phases of the venture (Klapper, 2011).

Moreover, we could (and indeed arguably should) intervene through seeking to strengthen the pro-social and pro-environmental norms that have become part of the habitus of individual entrepreneurs—for example, through targeted educational initiatives and messaging (e.g., Corner & Clarke, 2016; Schaefer, Williams, & Blundel, 2020). We might also provide environments for the building of relevant skills and competences and mindsets that promote different types of growth thinking. This would be consistent with a psychological approach to supporting a transition to more sustainable forms of entrepreneurship and it may have some success with some of those specifically targeted.

Yet a more generalised change in practices will also require a change in institutional incentives. A given practice forms a ‘block or bundle’ of ‘ways of doing’ (Gartner, Stam, Thompson, & Verduyn, 2016, p. 814) and is not easily undone. Undoing unsustainable practices requires attention to the incentives that direct and reinforce practices and the socio-material networks in which they are embedded, including the larger configurations or fields on which those practices depend (Warde, Welch, & Paddock, 2017).

APPENDIX A.

| Alias | Areas of business | Type of entrepreneur | Size of company | Cofounder | Education level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walter, mid 40s, male, postgraduate, married with children, significant international experience | From motor helmets, mobile phone covers to start-up consultancy | Serial | <10 or <100 depending on venture | Male | Undergraduate |

| Matti, late 20s, postgraduate, male, single, no children | From cosmetics to cloud computing | Serial | <10 | Female | Undergraduate |

| Thomas, postgraduate, male, late 20s, single, no children | Design company | Novice | <10 | Female | Postgraduate |

| Hannes, late 20s, postgraduate, male, no children | Design company | Novice | <10 | Female | Postgraduate |

| Andrew, early 30s, postgraduate, male, no children | International bookstore | CEO in family business | <100 | Family | Postgraduate |

| Michael, postgraduate, early 30s, male, no children | From records company to sushi restaurant | Serial | From less than 10 to 100 depending on venture | Male | Postgraduate |

| Mohammed, postgraduate, early 40s, male, no children, | Medical | Serial | <10 | Sole | PhD |

Linked In and e-postcard survey questions

Please define the following terms in your own words

- Personal details

- How do you define entrepreneurship?

- What is growth for you? Please define.

- What is innovation for you? Please define

- What is creativity for you? Please define

- What is out-of-the box thinking for you?

Starting questions for semistructured interviews with the entrepreneurs.

- Personal details (age, marital status, education, etc.)

- What was the first/second/third company you founded (products, location, team, customers, finance, etc.)?

- What is entrepreneurship for you? What are your aspirations as an entrepreneur? Any role models?

- How do you define growth? Do you want to grow and if yes why? Why not?

- How do you grow your business?

- What are the barriers to growth? Facilitators to growth.

- How do you see your company development in the next 12 months, 3 and 5 years?

- What is your recipe for growth?

Starting questions for the round table with entrepreneurs.

- Please introduce yourself

- Tell us about your entrepreneurial activities (companies you created, products/services, your team …)

- Please tell us about your definition of growth.

- Please tell us about growth in relation to your business

Thank you very much for your participation.

REFERENCES

- 1 Moreover, the interviewees were all male, though in three cases represented entrepreneurial ventures with a female cofounder, whom for reasons ranging from childcare to professional reasons were not available for either the semistructured interviews and/or the roundtable event. They were all followed up several times. One of the female founders was part of the audience of the roundtable, but when asked for an interview, she refused on the grounds that she was not engaged enough in the growth of the venture to be questioned for the study.

- 2 In terms of the World Values Survey, Inglehart and Welzel (2019) locate Finland in the group of Protestant northern European countries that score highly in terms of both secular-rational and self-expression values. Secular-rational values tend to be strong in countries with a long history of social democratic policies (Inglehart & Welzel, 2019).

- 3 The two domains are closely interrelated, as the authors of this review acknowledge: ‘Perhaps the notion of sustainable entrepreneurship needs some rewording (or reframing) and transitioning from divergence to convergence in the subfields will require a focus on purpose-driven entrepreneurship as an umbrella that integrates these subdomains, that is, social, environmental and sustainable entrepreneurship’ (Muñoz & Cohen, 2018, p. 317).