Determinants of Environmental Disclosure and Firm Value: Evidence From Latin American Energy and Mining Industries

Funding: This work was supported by Universidad de los Andes.

ABSTRACT

We developed an Environmental Disclosure Index (EDI) to capture a broad and detailed range of environmental issues. This comprehensive approach helps reduce the risk of superficial or selective reporting by firms. Using the EDI, we analyzed the factors associated with environmental disclosure practices among 220 companies in the energy and mining sectors in Latin America over the period 2015–2023. Additionally, we examined how the level of environmental disclosure is associated with a firm's value. We found that corporate governance is related to environmental disclosure. On one hand, larger, more independent, and diverse boards were associated with greater environmental reporting. On the other hand, CEO duality has a negative link with disclosure. Additionally, firms with concentrated ownership or a State as the largest shareholder disclosed more environmental information. We also found a positive relationship between environmental disclosure and a firm's value, suggesting that transparent environmental practices can enhance investor perceptions and market valuation. Our findings highlight that strong corporate governance can lead to more comprehensive environmental disclosure, a dynamic that has been less clearly established in the Latin American context, where governance standards and transparency practices are less developed. Firms with better governance are more likely to adopt sustainable practices, which may lead to greater alignment with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and higher valuation.

1 Introduction

The announcement of the SDGs for the 2030 Agenda has led firms to adopt proactive and effective roles in integrating sustainable strategies into their activities. Sustainability is a relevant issue for all firms in all industries. It is constructed on the belief that improving environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategies and performance promotes stronger durability, long-term value, and reduces risks (Hartzmark and Sussman 2019). Several stakeholders in the business field see ESG factors as a screen into a company's future, with ESG disclosure used as a tool to reveal firms' strategies towards sustainability (Husted and de Sousa-Filho 2019).

Using the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) reporting frameworks, we developed an Environmental Disclosure Index (EDI) to explore the determinants of environmental disclosure levels of 220 electricity, mining, and oil and gas firms in Latin America between 2015 and 2023, as well as its association with firm value. The development of the EDI addresses a key limitation in prior studies: existing disclosure practices often rely on the mere adoption of standards, which does not guarantee comprehensive or consistent reporting. In contrast, the EDI captures a broad and detailed range of environmental issues, enabling a more rigorous and nuanced analysis of disclosure practices and helping stakeholders identify firms that are genuinely aligned with SDGs.

Previous research about environmental reporting has focused on climate change disclosure (Amran et al. 2014; Giannarakis et al. 2018), environmental disclosure in North America, Europe, and Asia (Baalouch et al. 2019; Bamahros et al. 2022; Ezhilarasi and Kabra 2017; Hu and Loh 2018; Raimo et al. 2021), but studies have yet to focus on Latin American environmentally sensitive industries; this research fills that gap. These firms are essential for the region's economies and have been heavily criticized due to their negative environmental impact, but they are called to lead the transition towards a low-carbon world (Dincer 1999).

We found that environmental disclosure is positively associated with board characteristics such as size, independence, diversity, and negatively associated with CEO duality. We also observe that ownership concentration and a State as the largest shareholder are positively linked with firms' EDI. A positive association between environmental disclosure and firms value, measured as Tobin's Q, was also found. These findings suggest that good corporate governance mechanisms positively affect firms' disclosure practices and that companies engaging in transparent and comprehensive environmental reporting may be perceived more favorably by investors, stakeholders, and the broader market, thereby enhancing their performance and valuation in Latin America's electricity, mining, and oil and gas industries.

In Latin America, the effectiveness of good corporate governance practices cannot be taken for granted, as the institutional, legal, cultural, and economic foundations that support it in developed markets are often weak or inconsistent. The region's legal systems, rooted in French civil law, are associated with lower levels of investor protection and less developed capital markets compared to common law countries (La Porta et al. 1997). Unlike developed economies, Latin American firms frequently operate in contexts characterized by concentrated ownership (Céspedes et al. 2010), limited transparency, weak enforcement, and low judicial efficacy (Villarraga et al. 2012). These conditions underscore the importance of public policies aimed at strengthening companies' institutional and managerial capacities while promoting accountability, transparency, and effective governance (Klapper and Love 2004). Corporate governance is especially vital in Latin America, where investor rights are fragile and environmental and social vulnerabilities are significant. In this context, our findings emphasize that improving corporate governance is not only essential for investor protection and firm performance, but it also plays a pivotal role in enhancing environmental disclosure practices, which are key to achieving the SDGs, building trust, generating public policy recommendations to attract investment, and supporting sound decision-making in the region.

This study contributes in several ways to sustainable finance literature. First, we introduced a customized EDI, based on GRI and SASB standards, and specifically designed for the mining and energy sectors in Latin America. Second, it reveals that firms in Latin American environmentally sensitive industries are improving environmental disclosure practices based on environmental and financial standards. Third, we empirically show that good corporate practices and ownership structures are relevant in these opaque markets with high levels of information asymmetries, potentially reducing uncertainty regarding firms' environmental performance. Fourth, the positive association between environmental disclosure and firms' value may reflect the alignment of environmental and financial objectives in firms with strong governance practices. Finally, our work contributes to ongoing debates around the role of voluntary reporting frameworks, the importance of context in shaping disclosure practices, and the ways industry and region-specific factors influence environmental transparency in emerging markets.

The article is structured as follows: The second section provides a literature review and hypothesis development. The third part presents the methodology for data collection and analysis. The fourth segment shows the results of the research. The final section reveals the discussion and conclusions of the study.

2 Literature Review

Sustainable development presumes that resources are not infinite and should be used conservatively and consciously to guarantee that they are sufficient for future generations without lowering the present quality of life. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides a shared program for peace and prosperity for humans and the planet, now and into the future (United Nations 2022); at its center are the 17 SDGs. The SDGs' environmental dimension encompasses natural resource management, water-related and marine issues, biodiversity and ecosystems, climate change, and many other topics (United Nations Environment Programme 2020).

Electricity, mining, and oil and gas industries are often heavily criticized due to their negative environmental impacts that include, but are not limited to, the emission of pollutants (Dincer 1999). Despite those negative impacts, a growing market for minerals is expected due to their key role in the transition to a significantly lower carbon future (World Bank 2017) and to achieve the net zero 2050 goal proposed by the Paris Agreement (Huang and Zhai 2021).

In the case of the mining industry, Monteiro et al. (2019) argue that it must be committed to environmental concerns and work toward achieving the SDGs as the extraction of finite mineral resources has been argued to be unsustainable, reducing the ability of future generations to access those resources (Mudd 2007). This can be done by implementing strategies such as conducting thorough assessments of local geological conditions, ensuring environmental restoration postmining, and adopting sustainable practices to mitigate impacts on soil, water, and air quality. Such strategies are best accomplished through effective environmental management (Hilson and Murck 2000) and disclosure. Thus, public policies must be designed to incentivize and enforce these practices with sectoral reporting and data disaggregation, ensuring that the industry remains accountable and aligned with long-term environmental goals and inclusive socio-economic development (Cole and Broadhurst 2020).

The oil and gas industry is highly globalized, faces significant criticism on various sustainability issues, and is largely controlled by a few large companies, making CSR challenges more complex (Borges et al. 2022). The industry is divided into three key areas: upstream (exploration and production), midstream (storage, trade, and transportation of oil and gas), and downstream (refining, distribution, and retail). Each of these areas presents unique sustainability issues, making the approach to responsibility vary significantly depending on the business segment (Berkowitz et al. 2016). However, several companies have made reasonable efforts to disclose environmental performance indicators, particularly those relating to the protection and restoration of habitats, greenhouse gas emissions, and significant spills (Alazzani and Wan-Hussin 2013; Ahmad et al. 2016).

The electricity generation industry is among the most heavily regulated sectors as well. In addition to direct regulations, firms are also influenced by market-based mechanisms such as carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes (ETSs), which encourage improvements in environmental performance and greater investment in renewable energy. These pressures also drive companies to enhance their environmental image through disclosure. As public concern over CO2 emissions grows, firms are increasingly likely to respond with detailed environmental reporting (Alrazi et al. 2016).

Since the economies of many Latin American countries rely heavily on extractive industries because of the relative abundance of minerals (Husted and de Sousa-Filho 2019), and the demand for clean energy is expected to increase in the coming years, it is critical for these firms to improve their sustainable practices and supply chain efficiency (Norris et al. 2021).

The enhanced inquiry from investors, changes in client and customer prospects, and likely rule changes under new governments indicate firms face new pressure to voluntarily quantify, divulge, and improve environmental-related concerns. Environmental disclosure conveys the progress status toward environmental objectives as they represent a form of accountability to fulfill the firms' information needs for stakeholders (Mudd 2010; Solikhah and Maulina 2021). By disclosing environmental issues, firms reduce investors' incentives to obtain information privately, thus reducing information asymmetries about firms' real value, affecting the market price under the efficient market hypothesis (Akerlof 1970).

The development of reporting standards has been the focus of international organizations such as the United Nations (Gutterman 2021). Some of the relevant reporting initiatives are GRI, SASB, Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), and Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), and some stakeholders might favor one framework over the other, but they are eventually complementary, reciprocally supportive, and convergent. GRI and SASB are the most popular frameworks and standard-setting organizations (Gutterman 2021). The alignment of frameworks suggests that GRI works as the general disclosure standard, whereas SASB improves the reporting with more data-driven information, particularly oriented toward investors and suppliers of financial capital (GRI 2021). Many energy and mining companies report on their sustainability performance based on GRI or SASB standards (Mudd 2007).

2.1 Determinants of Environmental Disclosure

The growing relevance of environmental issues is also reflected in firms' corporate governance. The agency theory helps understand the relationship between agents and principals, whereas corporate governance moderates this association. The principal must reduce information asymmetries regarding agents' performance on the management task, and the firm's board attributes help to reduce these asymmetries and mitigate the agency problems (Eisenhardt 1989). Previous studies have shown how board and ownership characteristics impact the decisions of firms to disclose environmental information (de Villiers et al. 2011; Giannarakis et al. 2018, 2019; Husted and de Sousa-Filho 2019; Raimo et al. 2021). Therefore, we focus on these characteristics to explore their association with environmental disclosure.

2.1.1 Board Size

A board of directors is the governance structure of a company, chosen by shareholders in the case of public companies, with the fiduciary duty of advising, monitoring managers, and mitigating potential conflicts of interest derived from the separation of ownership and control (Bainbridge 1993). As described by Fama and Jensen (1983), a firm's board acts as an information system that the firm's shareholders use to monitor the opportunism of managers within the organization. Its size is represented by the absolute number of directors that are part of the organization (Morck et al. 1988).

The empirical evidence regarding the board size impact on environmental disclosure is mixed. The study of Ezhilarasi and Kabra (2017) showed a positive association in a sample of 177 Indian companies for the 2009–2015 period. Hu and Loh (2018) found a similar connection when investigating 462 firms in Singapore. Husted and de Sousa-Filho (2019) studied the ESG disclosure of 176 Latin American firms, and their findings also support this positive effect. Raimo et al. (2021) discovered similar evidence when observing ESG disclosures of 129 international firms. Bamahros et al. (2022) investigated the relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and ESG disclosures among Saudi companies, and their findings are also consistent with previous research.

Following the agency theory, bigger boards would include several educational and industrial backgrounds and experience with the skills required to tackle environmentally sensitive issues in the board agenda. From this perspective, it is claimed that a larger board is more prone to be watchful for agency problems because more people will supervise, control management actions, and promote more environmental disclosure practices (Kiel and Nicholson 2003), thereby contributing to the achievement of the SDGs.

For the reasons presented above, we hypothesize:

H1a.Board size has a positive association with environmental disclosure.

2.1.2 Board Independence

Boards consist of two types of directors, executive and nonexecutive, also called independent. Since the board is composed of experts, it is natural that some of its members are internal managers who have valuable specific information about the organization's activities (Fama and Jensen 1983). Executive directors are responsible for day-to-day areas such as finance and marketing and assist in creating and executing corporate strategy (Shleifer and Vishny 1997). Directors give specialized expertise and a variety of knowledge to the firm as full-time employees with specific roles and responsibilities. However, their subordination to the CEO weakens their position to supervise and control. That is why effective monitoring requires that some directors are independent of the executive directors on the board (Jensen 1993).

Some empirical evidence suggests that companies engaging in sustainability initiatives will likely have more independent directors. Liao et al. (2015) studied the 329 largest companies in the United Kingdom and found that higher participation of independent directors was associated with a higher level of ESG reporting. The research of Amran et al. (2014) included a set of 111 firms from diverse countries and reported similar results. The studies of Hu and Loh (2018), de Villiers et al. (2011), and Husted and Sousa-Filho (2019) are also consistent with this finding.

Independent directors are often chosen to improve decision-making and enhance access to valued resources (Fama and Jensen 1983). According to Husted and de Sousa-Filho (2019), they understand the relevance of community, environmental, and other stakeholder interests, so they promote higher environmental disclosure. Furthermore, independent directors might be more involved in philanthropic subjects associated with corporate social responsibility than executive directors, thus improving environmental disclosure.

Based on these arguments, we hypothesize:

H1b.Board independence has a positive association with environmental disclosure.

2.1.3 Board Diversity

The presence of women on corporate boards has been increasingly examined as a dimension of effective governance, with several studies highlighting their potential contribution to more responsible and inclusive decision-making (Bektur and Arzova 2020; Husted and de Sousa-Filho 2019; Naciti 2019; Dhar et al. 2024).

Women are usually more sympathetic to global matters, notably social and environmental concerns (Husted and de Sousa-Filho 2019; Arena et al. 2022). Gender diversity on the board might consider decisions associated with tackling global warming and involving sustainability matters confronted by every organization. Bart and McQueen (2013) consider that women on the board are more effective than men in sustainability decisions as they recognize the rights of others and pursue equality through cooperation. Moreover, board gender diversity aligns with the agency theory by improving board independence, reducing the conflict between the principal and the agent, supplying a clear direction on handling climate change issues, and representing the different types of stakeholders (Amran et al. 2014). Therefore, the presence of women on the board might enhance environmental disclosure, contributing to the achievement of the SDGs and holds significant public policy implications, as it suggests that promoting gender diversity in corporate governance can serve as a regulatory lever to encourage more transparent and sustainable business practices.

Some empirical evidence supports this view. Baalouch et al. (2019) found that the presence of women on boards was positively associated with the quality of environmental disclosure among French-listed firms. Similar findings were reported by Lavin and Montecinos-Pearce (2021) in their analysis of Chilean companies, as well as by Amran et al. (2014) and Raimo et al. (2021), who observed comparable patterns in other contexts.

Nevertheless, the evidence remains far from conclusive. Some studies, such as those by García-Sánchez et al. (2018) and Pizzi et al. (2020), did not identify a significant relationship between board gender diversity and sustainability disclosure. Others have reported mixed or even negative associations (Cucari et al. 2017; Giannarakis et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2012; Husted and de Sousa-Filho 2019). As noted by Wang et al. (2022), these divergent findings suggest that contextual factors such as the regulatory environment, industry characteristics, or national institutional frameworks may play a crucial role in shaping the relationship between board composition and disclosure practices.

This consideration is particularly relevant for firms in sectors such as electricity, mining, and oil and gas, which often face heightened scrutiny due to their environmental footprint and long-standing reputational challenges (Dincer 1999). In such contexts, greater board diversity may not only respond to external stakeholder expectations but also enhance the credibility and quality of environmental reporting.

Based on the previous discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1c.Board diversity has a positive association with environmental disclosure.

2.1.4 CEO Duality

A CEO duality occurs when an individual has the CEO role and the position of chairman of the board. The role of a chairman is to run board meetings and supervise the process of hiring, firing, evaluating, and compensating the CEO (Jensen 1993). Nevertheless, imparting the power of the CEO and chairperson of the board to one person may corrode the board's ability to exert effective control, potentially create conflicts of interest, and create the ethical need for self-monitoring (Fama and Jensen 1983; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Therefore, companies with CEO duality in the organization offer more extensive power to one person, allowing them to make choices that do not maximize shareholders' capital, improve the supervising quality, or decrease benefits from holding back information (Amran et al. 2014).

Empirical evidence also supports the negative relationship between CEO duality and environmental disclosure. The study by Naciti (2019) analyzed whether the composition of the board of directors affects firms' sustainability performance of 346 firms in 46 countries. The authors report that CEO duality presented a negative association with environmental disclosure. The studies of Amran et al. (2014) and Husted and de Sousa-Filho (2019) also found a negative association between CEO duality and environmental disclosure.

As the agency theory suggests, the separation of the board chair and CEO position improves the independence of the board (Fama and Jensen 1983), controls managerial opportunism, brings new knowledge, improves transparency, and decreases agency costs (Shleifer and Vishny 1997). As a result, it might also enhance environmental disclosure.

Based on the discussion presented above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1d.CEO duality is negatively associated with environmental disclosure.

2.1.5 Ownership Concentration

Ownership concentration is an important corporate governance tool that firm owners use to control and influence management, thus protecting their own interests and reducing agency problems (Jensen and Meckling 1976). The improved monitoring efficiency explains this effect as higher ownership concentration provides large shareholders with more incentives and power to examine management at lower costs (Grossman and Hart 1986). However, it may also generate agency conflicts between major and minor shareholders as the presence of cunning initiatives from the firm's controlling groups, together with weak protection of minority shareholders' property rights, might result in the former's wealth expropriation (Shleifer and Vishny 1997; Williamson 1988).

The literature examining the relationship between ownership concentration and environmental disclosure remains limited and presents inconsistent results. For instance, Huafang and Jianguo (2007), in their analysis of 559 Chinese firms, found that greater ownership by blockholders was linked to increased voluntary corporate disclosure. In contrast, studies by Chen et al. (2021) and Acar et al. (2021) identified a negative association. These divergent findings appear to depend on various firm-level and contextual factors, including industry (Chen et al. 2021; Lavin and Montecinos-Pearce 2021), country of operation (Acar et al. 2021), and the nature of the shareholder base (Calza et al. 2014). According to Céspedes et al. (2010), companies in Latin America typically have more concentrated ownership structures compared to those in more developed economies, due in part to a shared legal tradition rooted in French Civil Law, which tends to offer weaker investor protections than Common Law systems. In this context, higher levels of environmental disclosure in Latin American firms may be influenced by the presence of dominant shareholders.

When considering environmental sustainability and risks derived from these issues, large shareholders may focus on decision-making processes that improve a firm's environmental performance and long-term value. Therefore, they may use their control on management to disclose environmental information, reducing agency conflicts, signaling the firm's quality, and enhancing its reputation (Acar et al. 2021).

Based on the arguments presented above, we hypothesize:

H2a.Ownership concentration has a positive association with environmental disclosure.

2.1.6 State as the Largest Shareholder

Understanding firms' involvement in environmental activities also depends on the context of the country. In many Latin American countries, a State partially owns firms and stocks of many listed companies, even in polluting industries. Thus, it might influence CEOs towards political and environmental issues (Lu and Abeysekera 2014). A State might openly have policies to enhance the environment's quality via regulation or direct investment, and managers of State-owned firms may disclose environmental information to reflect environmental responsibility and positively impact the State's perception.

There is also evidence supporting this idea. Calza et al. (2014) studied 778 European firms and found that state-controlled firms are more environmentally proactive than their counterparts. Lau et al. (2016) also reported a positive association when studying the impact of board and ownership characteristics on the sustainability performance of 471 Chinese companies. Giannarakis et al. (2018) adopted a Climate Performance Leadership Index to study climate change disclosure for European companies and revealed a similar finding. The results of Arena et al. (2022) showed a similar association but were not empirically supported.

The presence of a State as the largest shareholder also helps mitigate the problems emerging from the divergence of interests between managers and shareholders concerning corporate environmental management, thus enhancing the firm's environmental strategies, such as disclosure (Calza et al. 2014). Moreover, State-controlled firms would engage more in sustainable activities to face normative pressure and be role models for their counterparts (Lau et al. 2016). This leadership position is especially relevant in environmentally sensitive industries where firms must be “responsible.” Therefore, State-controlled electricity, mining, and oil and gas companies have significant incentives to develop more sustainable practices and use environmental disclosure to signal them to the market.

Based on these arguments, we hypothesize:

H2b.A State, being the firm's largest shareholder, has a positive association with environmental disclosure.

2.2 Environmental Disclosure and Firm's Value

The relationship between environmental disclosure and firm's value, measured as Tobin's Q, has been a subject of increasing interest in recent years, but research has yielded mixed results. A study of Gulf Cooperation Council firms found a significant positive relationship between corporate environmental disclosure and Tobin's Q (Gerged et al. 2021). Similarly, in the European banking sector, environmental disclosure positively affected Tobin's Q (Buallay 2019). However, in China's heavy-pollution industries, environmental disclosure had a significantly negative association with Tobin's Q, whereas environmental propensity disclosure had a significantly positive effect (Chang 2015). These conflicting findings suggest that the relationship between environmental disclosure and firm value may vary depending on factors such as industry, region, and specific aspects of environmental disclosure.

In the context of environmental disclosure, the signaling theory argues that firms with high levels of transparency in environmental practices signal to the market that they are proactive in managing environmental risks and complying with regulatory standards (Dossa 2025). Investors often interpret strong environmental performance as indicative of a firm's long-term sustainability, risk management capabilities, and future growth prospects. As a result, these firms may experience a higher Tobin's Q, reflecting a greater market valuation relative to the replacement cost of their assets. In this sense, environmental disclosure acts as a signal of good corporate governance and management quality, increasing the firm's attractiveness to investors (Paridhi and Ritika 2025). Moreover, firms with high environmental performance are less likely to face regulatory fines, reputational damage, or litigation, all of which could negatively impact their market value. Thus, environmental disclosure can reduce information asymmetry between the firm and investors, decreasing uncertainty and improving the firm's market perception, ultimately leading to a higher Tobin's Q (Gerged et al. 2021).

Based on the previous arguments we hypothesize:

H3.Environmental disclosure has a positive association with firm's value.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data

Using Bloomberg, EMIS, and Refinitiv, we identified the total population of listed firms operating in the electricity, mining, and oil and gas industries across Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru from 2015 to 2023. These countries had the highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and represented the largest markets in Latin America and the Caribbean (World Bank 2022). Firm selection was determined by the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes. Table 1 shows the number of firms included in the study per industry and country of origin. A total of 220 reports or websites were collected and analyzed per year for the same set of companies, resulting in 1980 documents reviewed over the period studied.

| Panel A. NAICS code per industry | |

|---|---|

| NAICS code | Description |

| 211 | Oil and gas |

| 212 | Mining |

| 221 | Electric power generation, transmission, and distribution |

| Panel B. Firms per country and industry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Mexico | Peru | Subtotal | |

| Oil and gas | 10 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 30 |

| Mining | 2 | 20 | 13 | 2 | 15 | 22 | 74 |

| Electricity | 11 | 62 | 18 | 5 | 1 | 19 | 116 |

| Subtotal | 23 | 88 | 36 | 12 | 18 | 43 | 220 |

We used an index-based approach, specifically, a composite score based on the presence or absence of specific environmental disclosure items, to quantify the disclosure of environmental factors. The EDI is built upon the GRI and SASB frameworks, as these are widely adopted and mutually complementary (Schoenmaker and Schramade 2019) and support the use of quantitative indicators for reporting their performance related to the SDGs in a more objective way (Arena et al. 2022). The EDI enhances transparency and comparability by integrating the strengths of both standards into a unified, robust framework. Although existing standards vary in scope and application, the EDI bridges these differences by incorporating both the broad environmental focus of GRI and the sector-specific materiality emphasized by SASB. This dual perspective improves comparability across firms and industries while maintaining relevance to the operational realities of the energy and mining sectors.

Importantly, the EDI goes beyond basic compliance. It evaluates the depth and breadth of environmental disclosure across key areas such as resource use, ecological impact, and supply chain management, providing a more comprehensive measure of a firm's environmental accountability. Merely adhering to disclosure standards does not ensure comprehensive reporting, as firms may still choose to disclose information on only a limited range of environmental issues. The EDI addresses this limitation by reducing the risk of incomplete disclosures, thereby helping stakeholders identify companies that are genuinely committed to advancing SDGs.

For each category, based on GRI and SASB standards, we incorporated a set of equally weighted sub-categories covering issues such as consumption, management, and resource strategies to address environmental risks. The standards are focused on electricity, mining, and oil and gas industries, being 80 the maximum possible score in our index. A key attribute of the EDI is its ability to consistently capture comprehensive, comparable, and reliable information across all key environmental categories and firms, enhancing the validity of the analysis. As such, the EDI serves as an effective measure to assess firms' environmental management. Higher scores indicate greater disclosure and may signal a stronger capacity to reduce information asymmetries.

Our analysis aimed to identify specific key performance indicators (KPIs) in firms' disclosures to construct the EDI. The process began with the selection of data sources, where we used the sustainability report of each company, and in cases where a sustainability report was unavailable, we referred to the annual report or the company's website instead. The objective was to determine whether a company disclosed information corresponding to the criteria outlined in the EDI. We then selected the content by searching for each criterion listed in the EDI, such as fuel, water, energy, and waste. For each criterion, we manually searched for the relevant KPIs, including fuel consumed, water withdrawn, energy consumed, and scope 1 GHG emissions. A coding scheme was applied, where if a specific KPI was found, the corresponding unit of analysis was assigned a value of 1; if not, it was assigned a value of 0. Finally, we analyzed and interpreted the data by calculating the total number of units analyzed for each company based on the EDI criteria, which yielded the environmental disclosure score for each company.

Table 2 shows the categories of the EDI. We focused on managing five inputs of the production and distribution processes: fuels, water, chemicals, energy, and suppliers. We also included the administration of five outputs: ecological impact, greenhouse gas emissions, air quality, waste and hazardous materials, and biodiversity impact. Such categories were selected because they capture the most relevant environmental aspects of production in the energy and mining sectors. They are also aligned with GRI and SASB standards and reflect how firms manage critical inputs and address key environmental impacts that are essential for evaluating environmental performance and disclosure practices. The category “suppliers” accounts for negative impacts on the supply chain, including scope 3 GHG emissions (See Appendix A, items 40–43).

| Category | Number of sub-categories |

|---|---|

| Fuel | 5 |

| Water | 10 |

| Chemicals | 8 |

| Ecological impact | 10 |

| Greenhouse gas emissions | 10 |

| Air quality | 9 |

| Energy | 9 |

| Waste and hazardous materials | 8 |

| Biodiversity impacts | 9 |

| Suppliers | 2 |

| Total | 80 |

3.2 Firm Characteristics and Control Variables

The description of variables is shown in Table 3. All corporate governance variables were extracted from each company's annual reports, and financial variables were retrieved from the EMIS database. As Harris and Raviv (2008) proposed, we measured Board size as the number of directors on the board. Board independence was calculated as the ratio of independent directors on the boardtoboard size (Rosenstein and Wyatt 1990). Board diversity represented the ratio of women on the boardtoboard size (González et al. 2020). As Boyd (1995) recommended, CEO duality was a dummy variable equal to 1 (one) if the firm's CEO was also the president of the board and 0 (zero) otherwise. Ownership concentration (Ownership concentration) was determined by the percentage of common equity owned by the largest shareholder. Following Demsetz and Lehn (1985), the type of the firm's largest shareholder (State ownership) was represented as 1 (one) if a State is the largest shareholder of the company and 0 (zero) otherwise. Finally, founded on Wernerfelt and Montgomery (1988), we used Tobin's Q as a proxy for the firm's value. It represents the ratio of a firm's market value to the value of asset replacement.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |

| EDI | Total environmental disclosure. |

| Tobin Q | Firm's value: Tobins Q calculated as the ratio of market value to asset replacement value. |

| Independent variables | |

| Board size | Number of directors on the Board. |

| Board independence | Percentage of independent directors on the Board. |

| Board diversity | Percentage of women on the Board. |

| CEO duality | 1 if the CEO is also the President of the Board, 0 otherwise. |

| Ownership concentration | Percentage of equity owned by the largest shareholder. |

| State ownership | 1 if a State is the firm's largest shareholder, 0 otherwise. |

| Control variables | |

| Management turnover | 1 if the CEO was replaced, 0 otherwise. |

| Age | Number of year since firm's incorporation. |

| Size | Natural logarithm of firm's assets. |

| Size squared | Squared natural logarithm of the firm's assets. |

| Profitability | Operating ROA adjusted by industry. |

| Leverage | Debt-to-assets ratio. |

| Growth | 5-year average growth of assets. |

| EBIT volatility | The standard deviation of 5-year operating margin. |

| Audited | 1 if the ESG report was audited, 0 otherwise. |

| Argentina | 1 if the firm is from Argentina, 0 otherwise. |

| Brazil | 1 if the firm is from Brazil, 0 otherwise. |

| Chile | 1 if the firm is from Chile, 0 otherwise. |

| Colombia | 1 if the firm is from Colombia, 0 otherwise. |

| Mexico | 1 if the firm is from Mexico, 0 otherwise. |

| Peru | 1 if the firm is from Peru, 0 otherwise. |

- Note: Corporate governance variables were retrieved from the annual reports. Financial variables were collected from the EMIS database.

Our models include the following financial and control variables. Management turnover was measured as a dummy variable equal to 1 if the CEO was replaced in a given year, and 0 otherwise. This variable serves as a proxy for the effectiveness of the governance system. Firm size (Size) was measured as the natural logarithm of total assets in millions of dollars (Shalit and Sankar 1977), and Size squared was included to capture potential nonlinear effects. Firm age (Age) represents the number of years since the firm's incorporation. Profitability was measured as the adjusted operating return on assets (Mikkelson et al. 1997). Leverage was calculated as the ratio of total debt to the book value of financial assets (Lang et al. 1996). Growth was measured as the five-year average annual change in total assets. We also controlled for EBIT volatility, defined as the five-year average of the standard deviation of operating margins (Belo et al. 2015). These variables control for firms' characteristics and financial health and are widely used in the corporate governance literature. Additional controls included whether the ESG report was audited (Audited) and the firm's country of origin.

3.2.1 Data Analysis

- i represents the identity of the firm.

- t denotes the year.

- EDIit is the disclosure level of the firm i in year t.

- TQit is the Tobin's Q value for form i in year t

- α is a constant.

- βj is a coefficient representing the association of the independent variable (determinant) j with the disclosure level. The sign of the coefficient determines the association.

- βk is a coefficient representing the association of a control variable j with the disclosure level. The sign of the coefficient determines the association.

- Xjit is the independent variable j for the firm i in the year t.

- μ is the error term.

4 Results

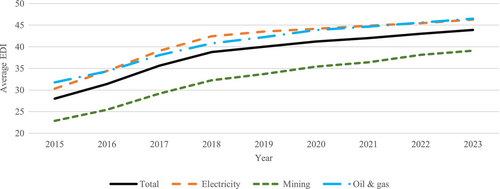

Figure 1 shows the evolution of environmental disclosure levels by industry and year based on the EDI and (Table 4). Presents descriptive statistics. We began the analysis in 2015 as this year is characterized by the signature of The Paris Agreement and the establishment of SDGs, two initiatives committed to controlling climate change and improving environmental sustainability.

| Variable | N | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| EDI | 1980 | 38.220 | 15.784 | 4.000 | 72.000 |

| Tobin's Q | 1057 | 0.769 | 0.481 | 0.000 | 2.990 |

| Independent variables | |||||

| Board size | 1980 | 7.518 | 2.632 | 3.000 | 17.000 |

| Board independence | 1980 | 0.271 | 0.212 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Board diversity | 1980 | 0.090 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.800 |

| CEO duality | 1980 | 0.044 | 0.206 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Ownership concentration | 1980 | 0.562 | 0.253 | 0.059 | 1.000 |

| State ownership | 1980 | 0.123 | 0.329 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Management turnover | 1980 | 0.157 | 0.364 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 1980 | 41.877 | 26.633 | 0.000 | 158.000 |

| Size | 1980 | 6.738 | 2.140 | −3.912 | 12.607 |

| Size squared | 1980 | 49.982 | 27.430 | 0.002 | 158.943 |

| Profitability | 1980 | 0.000 | 0.100 | −0.870 | 0.760 |

| Leverage | 1980 | 0.501 | 2.661 | −0.107 | 50.933 |

| Growth | 1760 | −0.030 | 0.818 | −7.997 | 8.290 |

| EBIT volatility | 1980 | 1.198 | 10.691 | 0.000 | 144.878 |

| Audited | 1980 | 0.199 | 0.399 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Argentina | 1980 | 0.105 | 0.306 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Brazil | 1980 | 0.400 | 0.490 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Chile | 1980 | 0.164 | 0.370 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Colombia | 1980 | 0.055 | 0.227 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Mexico | 1980 | 0.082 | 0.274 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Peru | 1980 | 0.195 | 0.397 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

The results show that firms from the electricity, mining, and oil and gas industries have improved on average their environmental disclosure levels. As Figure 1 presents, firms from the electricity industry began with a mean disclosure of 30.30 in 2015 and ended with 46.34 in 2023. A similar increase occurred in mining firms, as the average disclosure level in 2015 was 22.87 and 39.08 in 2023. The oil and gas industry had the highest reported levels, beginning with 31.77 and ending with 46.53. Such an increase in EDI is relevant as ESG disclosure is still not mandatory in the region. The EDI evaluates environmental disclosure levels for 10 categories. As shown in panel A of Table 5, “suppliers” was the category with the highest level of disclosure. For example, given a maximum score of 2 in this category, all years had an average of at least 1.780.

| Panel A. Average environmental disclosure | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category (max score) | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Fuel (5) | 1.559 | 1.795 | 1.986 | 2.209 | 2.227 | 2.455 | 2.600 | 2.723 | 2.773 |

| Water (10) | 4.854 | 5.331 | 6.068 | 6.545 | 6.740 | 6.745 | 6.796 | 6.950 | 7.500 |

| Chemicals (8) | 1.209 | 1.454 | 1.763 | 2.159 | 2.327 | 2.195 | 2.258 | 2.409 | 2.527 |

| Ecological (10) | 3.891 | 4.409 | 4.818 | 5.113 | 5.300 | 5.301 | 5.345 | 5.404 | 5.477 |

| GHG (10) | 4.131 | 4.736 | 5.318 | 5.663 | 5.736 | 5.909 | 6.036 | 6.127 | 6.245 |

| Air quality (9) | 1.814 | 2.063 | 2.495 | 2.891 | 2.954 | 3.436 | 3.650 | 3.795 | 3.858 |

| Energy (9) | 4.518 | 5.063 | 5.686 | 6.095 | 6.381 | 6.586 | 6.640 | 6.809 | 6.941 |

| Waste (8) | 1.978 | 2.300 | 2.677 | 2.995 | 3.118 | 3.195 | 3.245 | 3.290 | 3.345 |

| Biodiversity (9) | 2.227 | 2.422 | 2.900 | 3.227 | 3.368 | 3.459 | 3.527 | 3.573 | 3.627 |

| Suppliers (2) | 1.782 | 1.782 | 1.845 | 1.845 | 1.845 | 1.882 | 1.918 | 1.927 | 1.927 |

| Total (80) | 27.962 | 31.356 | 35.556 | 38.743 | 39.996 | 41.163 | 42.015 | 43.007 | 44.220 |

| Panel B. Average environmental disclosure in electricity industry | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category (max score) | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Fuel (5) | 1.889 | 2.198 | 2.362 | 2.638 | 2.612 | 2.850 | 3.000 | 3.103 | 3.129 |

| Water (10) | 5.551 | 6.086 | 6.965 | 7.491 | 7.594 | 7.387 | 7.370 | 7.517 | 7.819 |

| Chemicals (8) | 1.215 | 1.517 | 1.715 | 2.154 | 2.370 | 2.000 | 2.042 | 2.138 | 2.198 |

| Ecological (10) | 4.094 | 4.698 | 5.034 | 5.396 | 5.525 | 5.517 | 5.560 | 5.560 | 5.646 |

| GHG (10) | 4.543 | 5.387 | 5.965 | 6.267 | 6.284 | 6.396 | 6.508 | 6.568 | 6.698 |

| Air quality (9) | 1.844 | 2.034 | 2.715 | 3.241 | 3.318 | 3.784 | 4.051 | 4.094 | 4.129 |

| Energy (9) | 5.000 | 5.767 | 6.404 | 6.758 | 7.060 | 7.241 | 7.293 | 7.413 | 7.629 |

| Waste (8) | 1.845 | 2.206 | 2.767 | 3.060 | 3.190 | 3.198 | 3.241 | 3.258 | 3.302 |

| Biodiversity (9) | 2.474 | 2.680 | 3.198 | 3.508 | 3.620 | 3.810 | 3.862 | 3.870 | 3.836 |

| Suppliers (2) | 1.810 | 1.810 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 1.914 | 1.948 | 1.948 | 1.948 |

| Total (80) | 30.264 | 34.384 | 39.005 | 42.392 | 43.452 | 44.096 | 44.875 | 45.470 | 46.334 |

| Panel C. Average environmental disclosure in oil and gas industry | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category (max score) | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Fuel (5) | 2.000 | 2.200 | 2.600 | 2.667 | 2.700 | 3.200 | 3.267 | 3.300 | 3.367 |

| Water (10) | 5.300 | 5.633 | 6.233 | 6.433 | 6.733 | 6.733 | 6.800 | 6.933 | 7.200 |

| Chemicals (8) | 1.466 | 1.566 | 2.066 | 2.600 | 2.733 | 3.166 | 3.233 | 3.400 | 3.500 |

| Ecological (10) | 4.466 | 4.800 | 5.300 | 5.466 | 5.633 | 5.666 | 5.666 | 5.700 | 5.733 |

| GHG (10) | 4.700 | 5.066 | 5.800 | 6.266 | 6.466 | 6.533 | 6.766 | 6.866 | 7.033 |

| Air quality (9) | 2.366 | 2.933 | 2.966 | 3.200 | 3.366 | 3.633 | 3.700 | 3.800 | 3.767 |

| Energy (9) | 4.900 | 5.166 | 5.633 | 6.099 | 6.333 | 6.566 | 6.600 | 6.833 | 6.933 |

| Waste (8) | 2.666 | 2.833 | 2.966 | 3.200 | 3.200 | 3.200 | 3.266 | 3.366 | 3.466 |

| Biodiversity (9) | 2.000 | 2.233 | 2.633 | 2.933 | 3.166 | 3.233 | 3.399 | 3.366 | 3.587 |

| Suppliers (2) | 1.800 | 1.800 | 1.800 | 1.800 | 1.800 | 1.933 | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 |

| Total (80) | 31.664 | 34.230 | 37.998 | 40.663 | 42.130 | 43.864 | 44.697 | 45.564 | 46.585 |

| Panel D. Average environmental disclosure in mining industry | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category (max score) | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Fuel (5) | 0.865 | 1.000 | 1.149 | 1.351 | 1.432 | 1.473 | 1.703 | 1.892 | 1.973 |

| Water (10) | 3.581 | 4.027 | 4.594 | 5.108 | 5.405 | 5.743 | 5.891 | 6.067 | 6.229 |

| Chemicals (8) | 1.094 | 1.310 | 1.716 | 1.986 | 2.094 | 2.108 | 2.202 | 2.432 | 2.648 |

| Ecological (10) | 3.337 | 3.797 | 4.283 | 4.527 | 4.810 | 4.837 | 4.878 | 5.040 | 5.108 |

| GHG (10) | 3.256 | 3.581 | 4.108 | 4.473 | 4.581 | 4.891 | 5.000 | 5.135 | 5.216 |

| Air quality (9) | 1.540 | 1.756 | 1.959 | 2.216 | 2.216 | 2.811 | 3.000 | 3.324 | 3.472 |

| Energy (9) | 3.600 | 3.919 | 4.581 | 5.054 | 5.337 | 5.567 | 5.635 | 5.850 | 5.864 |

| Waste (8) | 1.918 | 2.230 | 2.418 | 2.810 | 2.973 | 3.195 | 3.245 | 3.310 | 3.365 |

| Biodiversity (9) | 1.932 | 2.094 | 2.540 | 2.905 | 3.594 | 3.000 | 3.054 | 3.189 | 3.337 |

| Suppliers (2) | 1.730 | 1.730 | 1.811 | 1.811 | 1.811 | 1.811 | 1.838 | 1.865 | 1.865 |

| Total (80) | 22.853 | 25.443 | 29.159 | 32.241 | 34.253 | 35.435 | 36.445 | 38.103 | 39.077 |

Panel B presents the average environmental disclosure for the electricity industry. The average percentage of environmental disclosure for the oil and gas industry is shown in Panel C, and Panel D reports the average EDI for the mining industry. The lower level of environmental disclosure in the mining industry, compared to oil and gas and electricity, may reflect the sector's limited direct exposure to consumers and, consequently, lower brand awareness. However, this does not reduce the relevance of transparency. In the absence of strong consumer-facing brands, mining firms rely heavily on their reputational standing with investors, regulators, and local communities. Limited disclosure may signal weak governance or raise concerns about environmental and social risks, potentially undermining trust. In this context, environmental transparency becomes a key mechanism for building credibility and maintaining the social license to operate, even without traditional brand recognition.

The results of the panel data analysis are presented in Table 6. We developed four models to examine the association of firm characteristics and the EDI, as well as to test the robustness of our coefficients. Model (1) includes corporate governance variables, whereas Model (2) adds ownership characteristics; both represent a balanced panel as complete data were available for all variables for all firms. Model (3) incorporates age and financial control variables, and Model (4) appends the presence of an audited ESG report and country controls. Models (3) and (4) represent an unbalanced panel due to missing EBIT's data for the first year that was required to calculate the firm's growth for the next year.

| Variable | EDI | EDI | EDI | EDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Board size | 1.866*** | 1.851*** | 0.889*** | 1.106*** |

| Board independence | 22.800*** | 22.837*** | 13.969*** | 14.343*** |

| Board diversity | 14.225*** | 14.605*** | 14.204*** | 7.475*** |

| CEO duality | −1.307 | −2.940** | −2.521** | −3.204*** |

| Ownership concentration | 7.523*** | 4.551*** | 4.910*** | |

| State ownership | 6.378*** | 4.292*** | 2.326*** | |

| Management turnover | 0.845* | 0.815* | ||

| Age | −0.042*** | −0.007 | ||

| Size | 2.598*** | 3.924*** | ||

| Size squared | 0.050* | −0.096*** | ||

| Profitability | 16.076*** | 18.192*** | ||

| Leverage | 0.229** | 0.260*** | ||

| Growth | 0.409 | 0.343 | ||

| EBIT volatility | −0.117*** | −0.129** | ||

| Audited | 8.083*** | |||

| Argentina | 0.287 | |||

| Brazil | −1.204* | |||

| Chile | −3.056*** | |||

| Colombia | −4.235*** | |||

| Mexico | −11.043*** | |||

| Peru | — | |||

| Constant | 16.846*** | 11.647*** | 4.960*** | 1.346 |

| Observations | 1944 | 1944 | 1628 | 1628 |

| Number of id | 220 | 220 | 212 | 212 |

| Financial controls | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | No | No | No | Yes |

- Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

When assessing corporate governance variables in model (1), we found that board size, independence, and diversity had positive and significant coefficients at the 1% level. Therefore, an increase in any of these variables is associated with improved environmental disclosure. Model (2) added the firm's ownership characteristics and confirmed the sign and significance of previous coefficients. CEO duality obtained a negative and significant coefficient, which suggests that not separating the board chair and CEO position is related to reduced environmental disclosure levels. Ownership concentration revealed a positive and significant coefficient, and the EDI is higher when a state controls the firm.

Our Model (3) includes age and financial controls. Board size, independence, diversity, CEO duality, ownership concentration, and State ownership coefficients preserve their signs and significance. The results show that firm size and profitability are positively and significantly associated with environmental disclosure, suggesting that larger and more profitable firms are better positioned to respond to stakeholder expectations and allocate resources toward sustainability reporting. Age and EBIT volatility had negative and significant coefficients. This may indicate that younger firms are more responsive to evolving ESG standards, whereas firms with more stable earnings are better able to plan and sustain disclosure efforts over time.

As for Model (4), all relevant coefficients preserve sign and significance of at least 5%. An increase of one in the board's size increases EDI by 1.10 points, a boost of 10% in the ratio of independent directors is associated with 1.43 higher EDI, and an increase of 10% in the board's diversity ratio enhances EDI by 0.74 points. These coefficients are significant in all models. A CEO being also the Chair of the board reduces EDI by 3.20 points. Therefore, these results are consistent with our H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d. Model (4) also suggested that an increase of 10% in ownership concentration is associated with a higher environmental disclosure by 0.49 points and that firms controlled by a State disclose 2.32 more points on average than privately controlled firms. These findings are consistent with the stated H2a and H2b.

When analyzing control variables, we found an association mainly consistent across models. We expected a positive and significant relationship between firms' size and EDI because larger firms draw more attention from media, policymakers, and regulators and face greater pressure to act consistent with requirements (Watts and Zimmerman 1990). The estimated coefficients were positive and significant at the 1% level.

A positive relationship between EDI and the firm's profitability was expected as firms with high financial performance can invest more resources to improve ESG sustainability and increase their accountability (Alsaifi et al. 2020). Therefore, they are more likely to disclose information regarding environmental management. Model (4) indicates that an increase of 10% in adjusted ROA is associated with an increased EDI of 1.75. We also anticipated a positive association between EDI and leverage (Leverage) because creditors typically impose limitations or constraints when supplying credit. The bigger the debt, the bigger the creditor's power over the firm. Consequently, CEOs of companies with higher levels of debt might voluntarily disclose more information to reduce information asymmetries with stakeholders. Models (3) and (4) confirmed our expectations. Similarly, the relationship between a firm's growth and EDI was projected to be positive because firms with high growth rates may disclose more information, including environmental issues, especially when their projects are financed with external sources as their creditors usually demand more information (Khurana et al. 2006). However, the models did not show significant coefficients. Firms with audited ESG reports disclose 8 more points of environmental information than their counterparts; country controls indicate average disclosure versus the base group. For instance, firms from Brazil have on average, 1.024 lower EDI than their counterparts.

We then explored the association of environmental disclosure with firm's value. To validate the robustness of our estimation, we developed four models, which are presented in Table 7. Model (1) includes the EDI and corporate governance variables. We found positive and significant associations between firm Tobin's Q, environmental disclosure, and board size. Board diversity and CEO duality were excluded from the final models due to their limited explanatory power and lack of statistical significance in relation to firm value, which affected model consistency. Model (2) incorporates ownership characteristics. EDI, board size, and ownership concentration have positive and significant associations with firm's value, whereas State ownership shows a negative and significant coefficient.

| Variable | (1) Tobin Q | (2) Tobin Q | (3) Tobin Q | (4) Tobin Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental disclosure | 0.002*** | 0.002*** | 0.001** | 0.001** |

| Board size | 0.067*** | 0.068*** | 0.034*** | 0.040*** |

| Board independence | 0.024 | 0.039 | 0.129*** | 0.101** |

| Management turnover | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| Ownership concentration | 0.064** | 0.098*** | 0.129*** | |

| State ownership | −0.056*** | −0.073*** | −0.170*** | |

| Age | −0.002*** | −0.001*** | ||

| Firm's size | 0.162*** | 0.160*** | ||

| Firm's size squared | −0.011*** | −0.010*** | ||

| Leverage | 0.449*** | 0.350*** | ||

| Growth | −0.073*** | −0.062*** | ||

| EBIT volatility | 0.053*** | 0.065*** | ||

| Audited | −0.025 | |||

| Argentina | −0.013 | |||

| Brazil | 0.171*** | |||

| Chile | −0.025 | |||

| Colombia | 0.089** | |||

| Mexico | 0.038 | |||

| Peru | — | |||

| Constant | 0.422*** | 0.379*** | −0.111 | −0.217** |

| Observations | 1199 | 1199 | 1057 | 1057 |

| Number of id | 163 | 163 | 156 | 156 |

| Financial controls | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Country controls | No | No | No | Yes |

- Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Model (3) adds financial controls. Previous coefficients preserve signs and remain significant. Firm's age and growth show negative and significant coefficients; firm's size, leverage, and EBIT volatility reveal positive and significant associations with firm's value. Model (4) includes country controls. On one hand, environmental disclosure, board size, board independence, ownership concentration, firm's size, leverage, and EBIT volatility show positive and significant associations with Tobin's Q. On the other hand, State ownership, age, and growth show negative and significant associations with firm's value. A rise of 10 points in EDI is associated with a 0.01 higher Tobin's Q. An increase of one in the board of directors is related to a 0.040 higher Tobin's Q. A boost of 10% in board independence and ownership concentration is linked to a 0.01 and 0.013 greater Tobin's Q, respectively. Firm's size, leverage, and EBIT volatility have positive and significant associations with firm value, whereas State ownership, age, and growth have negative and significant associations with company's valuation. Since environmental disclosure has a positive association with firm's value across all models, we confirm H3.

4.1 Endogeneity

- ISO 14001: Environmental management system.

- ISO 50001: Energy management system.

- ISO 14064: Reports greenhouse gas emissions.

- ISO 14067: Carbon footprint of a product.

- EMAS: It enhances a firm's environmental performance, saves energy, optimizes resource usage, and improves environmental performance (European Comission 2022).

The results of the IV approach are shown in Table 8. The estimation shows a positive and significant association between environmental disclosure and firm's value. Specifically, an increase of 10 points in the EDI is associated with a 0.09 boost in Tobin's Q. Panel B displays usual tests for the robustness of the IV regression.

| Panel A. IV regression using the number of environmental management systems (EMS) | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Tobin Q |

| Environmental disclosure | 0.009*** |

| Board size | 0.066** |

| Board independence | −0.123 |

| Management turnover | 0.025 |

| Ownership concentration | 0.009 |

| State ownership | −0.145*** |

| Constant | 0.252** |

| Observations | 1199 |

| Panel B. First-stage regression summary statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | R 2 | Adj R2 | Partial R2 | F (1,1191) | Prob > F |

| Lagged environmental disclosure | 0.381 | 0.378 | 0.140 | 194.530 | 0.000 |

| Minimum eigenvalue statistic | 194.530 | ||||

| Critical values | # of endogenous regressors: | 1 | |||

| Ho: Instruments are weak | # of excluded instruments: | 1 | |||

| 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% | ||

| 2SLS size of nominal 5% Wald test | 16.380 | 8.960 | 6.660 | 5.530 | |

| LIML size of nominal 5% Wald test | 16.380 | 8.960 | 6.660 | 5.530 | |

- Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we developed a customized EDI based on GRI and SASB standards, specifically adapted to the mining and energy sectors in Latin America, which have been underexplored despite their environmental significance. Our work advances debates on context-specific disclosure practices, the effectiveness of voluntary reporting frameworks, and how industry and region-specific pressures shape environmental transparency in emerging economies. We also investigated the determinants of environmental disclosure and its association with firms value, of 220 electricity, mining, and oil and gas companies in Latin America. These firms typically use environmental disclosure to communicate their strategies, impacts, commitments, achievements regarding environmental sustainability to stakeholders, and alignment with global frameworks like the Paris Agreement and the SDGs.

We found empirical evidence that the board of directors, the governance figure of a company, is associated with the firm's environmental disclosure, as the coefficients were positive and significant in all models. This finding suggests that firms with large boards prevent potential agency problems by supervising, controlling management actions, promoting more sustainable practices, and signaling them with environmental disclosure.

When exploring the association of board independence with environmental disclosure, we found positive and significant coefficients. This result indicates that the role of independent directors in supervising and controlling CEOs is crucial to improving disclosure as they are more involved in sustainability and corporate responsibility activities. Independent directors may bring more diverse perspectives to board deliberations and enable broader consideration of firm impacts on stakeholders, which can enhance a company's ability to address environmental challenges and align with the SDGs, particularly SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production) and SDG 13 (Climate action).

Similarly, evaluating the board's diversity link with environmental disclosure produced a similar result as the variable's coefficient was positive and significant. This finding suggests that a more diverse board, particularly one that includes women, might be more familiar with global sustainability issues, which could encourage decision-making in favor of improving environmental disclosure. The positive relationship between board diversity and disclosure also aligns with the SDGs' emphasis on SDG 5 (Gender equality), as diverse boards may help improve corporate governance, reduce agency conflicts, and provide clearer direction in tackling environmental issues.

The association of EDI with ownership concentration was also positive and significant. According to Céspedes et al. (2010), Latin American firms exhibit high ownership concentration, so a positive relationship between this variable and EDI was expected. As the agency theory suggests, the presence of large shareholders is relevant in firms' decision-making processes since they supervise CEO decisions and mitigate inefficient behavior. Moreover, because environmental disclosure aims to maximize the value of stakeholders committed to sustainable development, higher ownership concentration may improve environmental disclosure, which aligns with SDG 17 (Partnership for the goals).

Contrary to other empirical research (Arena et al. 2022), the type of the largest shareholder was also relevant as it had a positive and significant association with EDI. In many Latin American countries, the State partially owns firms and stocks of listed companies, even in polluting industries, and influences CEOs' actions toward political and environmental issues. Some States aim to enhance the environment's quality through direct investment (Calza et al. 2014). As Wang et al. (2008) argue, State-owned firms are likely to present significantly greater adverse selection and moral hazard problems due to possible political ends. Therefore, they face incentives to voluntarily disclose additional information and ease investor concerns regarding management quality and the potential for asset stripping or misappropriation. Governments, through State-owned enterprises, may drive additional investments in green technologies and actively contribute to achieving SDG 7 (Affordable and clean energy) and SDG 13 (Climate action), both key components of the global commitment to addressing climate change.

The finding of a positive association between environmental disclosure and a firm's value, measured by Tobin's Q, holds significant implications for both theory and practice in the fields of corporate governance, environmental management, and sustainability. This association suggests that firms engaging in transparent and comprehensive environmental reporting may be perceived more favorably by investors, stakeholders, and the broader market, thereby enhancing their performance and valuation. The positive relationship indicates that markets may reward firms for providing detailed and reliable information on their environmental practices. Investors often perceive firms with high levels of transparency as lower-risk investments, as these firms are more likely to be managing environmental risks proactively and complying with regulatory requirements. The disclosure of environmental initiatives signals corporate responsibility, potentially leading to better investor confidence and, consequently, higher market valuation. Environmental transparency can also be seen as a proxy for effective risk management. Investors may interpret the disclosure of environmental policies, performance, and targets as evidence that a company is well-positioned to handle future regulatory changes, environmental challenges, and evolving consumer preferences for sustainability. This perception could increase demand for the firm's stock, driving up its market value.

Firms with strong environmental records and transparent communication on sustainability issues are generally better positioned to strengthen their reputational standing. Even in industries like mining where brand awareness is limited and there is no direct link to consumers, such disclosure can positively affect investor perception, community relations, and regulatory scrutiny. Clear and credible environmental reporting can enhance a firm's image among key stakeholders, including employees, policymakers, and the broader public. This, in turn, may support customer loyalty, talent retention, and potentially greater market share. Firms perceived as environmentally responsible may also command premium pricing, contributing to stronger financial performance and higher market valuations.

Transparent environmental disclosure can also signal that a company is effectively managing its environmental impact, which may translate into cost savings and operational efficiencies. For example, companies that disclose their efforts to reduce energy consumption, waste, or carbon emissions often demonstrate a commitment to long-term sustainability that includes reducing operational costs. Moreover, firms that actively track and report on their environmental impact are likely to have more efficient operations, as they may be more inclined to adopt green technologies, streamline supply chains, or implement sustainability practices that reduce waste or improve resource efficiency, all of which can contribute to higher profitability and valuation.

Our findings also suggest that firms with robust governance structures are more likely to prioritize environmental issues, which can result in better long-term strategic decision-making and ultimately better valuation. Boards that are independent and diverse may be more effective in overseeing and guiding corporate environmental strategies, leading to more comprehensive and actionable environmental disclosures. Additionally, good governance practices can improve the alignment between managerial decisions and shareholder interests. Firms that disclose their environmental management transparently may be more accountable to their investors, leading to better long-term value creation. The positive association between environmental disclosure and a firm's value may thus reflect the alignment of environmental and financial objectives in firms with strong governance practices.

6 Limitations and Future Research

This study had various limitations that may be useful for future research. First, the sample was limited to 220 listed firms in the energy and mining industries from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. Although these countries represented more than 80% of Latin American GDP in 2022, firms from other countries might be important players in the energy and mining industries. Moreover, large firms with foreign capital also operate in the region. Therefore, a generalization of the results provided in this study must be conducted carefully.

Second, although we distinguished between electricity, mining, and oil and gas industries, our analysis assumed a level of homogeneity within each sector that may overlook important intra-industry differences. For instance, firms from generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity are treated as equal. Companies involved in electricity generation versus transmission or distribution may face different disclosure expectations, just as coal and lithium miners face different environmental risks and stakeholder pressures. Future studies could explore these differences in greater detail, integrating more detailed industry classifications to better capture the diversity of disclosure practices.

Third, while we focused on governance and ownership structures as determinants of environmental disclosure, future research may explore supply chain differences within industries. Additionally, a large wave of mergers and acquisitions took place during the 2015–2023 period, especially in the electricity industry, which influences disclosure practices as European and North American firms investing in Latin America tend to voluntarily disclose more information. As more information is available, a deeper analysis of these determinants might be developed.

Fourth, future research should build stronger empirical links between firm-level disclosure practices and broader policy frameworks. For instance, studies might investigate whether firms in countries more committed to climate policy disclose more environmental information, or how alignment with the SDGs is communicated in corporate reports. This would deepen the understanding of how international sustainability agendas are interpreted and operationalized at the firm level in Latin America.

Finally, the EDI offers a practical tool for assessing the transparency of environmental reporting in high-impact sectors. Since its design was based on internationally recognized standards, it might be adaptable for comparative research across regions and industries. Future studies can use the EDI to track disclosure trends over time, evaluate the effects of policy changes, or explore the relationship between transparency and environmental performance in emerging economies.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A: Environmental Disclosure Index

| Category | Subcategory | Disclosure item |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel | Fuel management | 1. Does the company disclose the total amount of fuel consumed? |

| Fuel management | 2. Does the company disclose the percentage of renewable fuel used? | |

| Fuel management | 3. Does the company disclose its detailed use of fuel? | |

| Strategies | 4. Does the company disclose an analysis of fuel management performance? | |

| Strategies | 5. Does the company disclose the activities and/or investments made to improve efficiency in fuel consumption? | |

| Water | Use of fresh water | 6. Does the company disclose the amount of water withdrawn from freshwater sources? |

| Use of fresh water | 7. Does the company disclose the amount of water consumed in its operations? | |

| Use of fresh water | 8. Does the company disclose the amount of water recycled for production processes? | |

| Use of fresh water | 9. Does the company disclose its water disposal practices? | |

| Use of fresh water | 10. Does the company disclose its water-stressed regions and the amount of water withdrawn from these sources? | |

| Strategies | 11. Does the company disclose its strategies for water management? | |

| Strategies | 12. Does the company disclose an analysis of water management performance? | |

| Strategies | 13. Does the company disclose its plans to reduce water consumption? | |

| Strategies | 14. Does the company disclose the activities and/or investments to reduce water consumption? | |

| Strategies | 15. Does the company disclose the risks and opportunities related to water management? | |

| Chemicals | Hydraulic fracturing used | 16. Does the company disclose the amount of hydraulic fracturing used? |

| Hydraulic fracturing used | 17. Does the company disclose the percentage of hazardous materials used in hydraulic fracturing? | |

| Hydraulic fracturing used | 18. Does the company disclose the hydraulic fracturing techniques used and their influence? | |

| Strategies | 19. Does the company disclose its strategies for chemical management | |

| Strategies | 20. Does the company disclose an analysis of chemical management performance? | |

| Strategies | 21. Does the company disclose its plans to reduce chemical consumption? | |

| Strategies | 22. Does the company disclose the activities and/or investments made to reduce chemical consumption? | |

| Strategies | 23. Does the company disclose the risks and opportunities of chemical consumption? | |

| Ecological impact | Disturbed land | 24. Does the company disclose the disturbed land for exploration? |

| Disturbed land | 25. Does the company disclose the disturbed land for development? | |

| Disturbed land | 26. Does the company disclose the disturbed land for production? | |

| Disturbed land | 27. Does the company disclose the disturbed land for decommissioning? | |

| Strategies | 28. Does the company disclose its scope of activities regarding ecological impact? | |

| Strategies | 29. Does the company disclose its plans to mitigate ecological impact risks? | |

| Strategies | 30. Does the company disclose an analysis of ecological impact performance? | |

| Strategies | 31. Does the company disclose the activities and/or investments to mitigate ecological impact? | |

| Strategies | 32. Does the company disclose the risks and opportunities related to the management of ecological impact? | |

| Fines and penalties | 33. Does the company disclose the fines and penalties received due to not managing ecological impact? | |

| Greehouse gas emissions | GHG emissions (Kyoto protocol) | 34. Does the company disclose the global scope 1 GHG emissions of the seven GHGs the Kyoto Protocol covers? |

| GHG emissions (Kyoto protocol) | 35. Does the company disclose the percentage of scope 1 GHG emissions covered under emissions-limiting programs? | |

| GHG emissions (Kyoto protocol) | 36. Does the company disclose the scope 1 GHG emissions changes compared to previous years? | |

| Methodology | 37. Does the company disclose a description of the methodology to measure GHG emissions? | |

| Emissions covered under a regulation program | 38. Does the company disclose the percentage of GHG emissions covered under a regulation program? | |

| Strategies | 39. Does the company disclose its short and long-term scope 1 GHG emissions management strategies? | |

| Strategies | 40. Does the company disclose an analysis of GHG emissions' performance? | |

| Strategies | 41. Does the company disclose its plans to reduce GHG emissions? | |

| Strategies | 42. Does the company disclose its activities and/or investments to reduce GHG emissions? | |

| Strategies | 43. Does the company disclose the risks and opportunities related to its GHG emissions strategies? | |

| Air quality | Emissions | 44. Does the company disclose its emissions of carbon oxides (COX)? |

| Emissions | 45. Does the company disclose its emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOX)? | |

| Emissions | 46. Does the company disclose its emissions of sulfur oxide (SOX)? | |

| Emissions | 47. Does the company disclose non-methane volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emissions? | |

| Emissions | 48. Does the company disclose its emissions of particulate matter (PM)? | |

| Emissions | 49. Does the company disclose its emissions of mercury? | |

| Emissions | 50. Does the company disclose its emissions of lead and compounds? | |

| Strategies | 51. Does the company disclose its activities and/or investments to improve air quality? | |

| Strategies | 52. Does the company disclose its risks and opportunities related to air quality management? | |

| Energy | Energy management | 53. Does the company disclose the total amount of energy consumed as an aggregate figure? |

| Energy management | 54. Does the company disclose the percentage of energy consumed from grid electricity? | |

| Energy management | 55. Does the company disclose the percentage of renewable energy consumed? | |

| Strategies | 56. Does the company disclose its energy intensity? | |

| Strategies | 57. Does the company disclose its strategies for energy management? | |

| Strategies | 58. Does the company disclose an analysis of energy management performance? | |

| Strategies | 59. Does the company disclose its plans and targets to reduce energy intensity? | |