Antecedents to Implementing Green Practices in the Hotel Industry: The Role of Managers' Environmental Attitude, Perceived Organizational Environmental Support and Employees' Green Collaboration

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the role of managerial influence in the implementation of green practices (IGP) within the hotel industry, focusing on three key factors: managers' attitudes toward the environment (MAE), perceived organizational environmental support (POES), and employees' green collaboration (EGC). Drawing upon the Norm Activation Model, the Theory of Planned Behavior, and the Social Exchange Theory, the proposed model was tested using a sample of 190 hotel managers in India. The findings indicate that MAE indirectly influences the implementation of green practices through the managers' intentions to behave. In addition, both POES and EGC are directly related to the IGP. This holds particular relevance for India's hospitality sector, which faces considerable environmental challenges stemming from increasing tourist arrivals. By underscoring the internal antecedents of green practices, we offer practical strategies within managerial control to mitigate the industry's environmental impact.

1 Introduction

The tourism and, in particular, the hospitality industry, has emerged as one of the fastest-growing sectors and a key driver of economic development worldwide (Jones et al. 2017). This industry accounted for approximately 9.1% of global GDP, with international spending rising by 33% to $ 1.63 trillion (WTTC 2024).

Although the hotel industry has made notable efforts in recent years to reduce the environmental impact of its operations (Prakash et al. 2023), several studies (e.g., Acheampong and Opoku 2023; Dimara et al. 2017; Sharma and Bhat 2023) have highlighted its significant contribution to environmental degradation worldwide. Hotels are known to consume substantial amounts of water, energy, and natural resources. In response to these environmental challenges, the industry has increasingly embraced the adoption of green practices (Abdou et al. 2020).

Green practices are defined as initiatives that enable organizations to “doing business in a way that reduces waste, conserves energy, and generally promotes environmental health” (Rahman et al. 2012, 721). While some hotels have already adopted green practices, others have not. This disparity is especially pronounced in developing countries, where the level of implementation of green practices often differs from that in developed nations due to factors such as the prevalence of informal economies, high poverty rates, limited resources, insufficient knowledge, and awareness (Singjai et al. 2018), as well as the lack of legislation and transparency regarding green practices (OECD 2012). Consequently, examining the factors that drive hotels in developing countries to implement green practices is a compelling area of research.

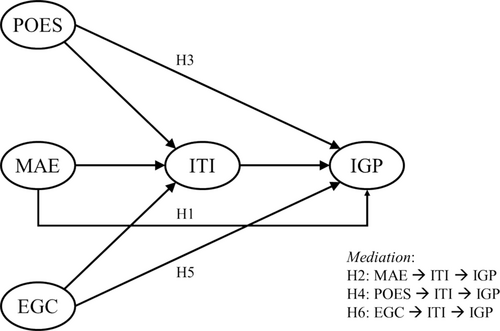

In light of these considerations, this article aims to analyze the role of managers' attitudes toward the environment, perceived organizational environmental support, and employees' green collaboration in the implementation of green practices within the hospitality sector, with a particular focus on the mediating role of the intention to implement the green practices.

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) offers a valuable theoretical lens through which to examine the relationship between managers' attitudes toward the environment and the implementation of green practices, as TPB links attitudes (e.g., attitudes toward the environment) to behavioral intentions and actual behaviors (e.g., implementing green practices). However, existing literature on the antecedents of green practices rarely incorporates this behavioral perspective, often prioritizing other drivers such as internal pressure (Arhavbarien et al. 2024), external pressures (Khan et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021), customer demand for environmentally friendly products (Pegan et al. 2023), or the influence of incentives and training toward pro-environmental behavior (Jakhar et al. 2020). Thus, a deeper exploration of the relationship between managers' attitudes toward the environment, their behavioral intentions, and the adoption of green practices is necessary.

Previous research has also demonstrated that POES can effectively promote pro-environmental behavior (Karatepe et al. 2022; Saifulina et al. 2021). However, there is limited research on how POES influences managers' intentions and the implementation of green practices within the hotel industry.

Recent studies (Deshpande et al. 2024; Jung et al. 2023) have underscored the pivotal role of employees in achieving future sustainability goals in the hotel industry. In addition to managers' attitudes and POES, employees' collaboration is increasingly recognized as a key antecedent in the adoption of green practices. Employees can support managerial efforts through actions such as minimizing water consumption, turning off lights and electronic equipment when not in use, recycling as much waste as possible, generating e-slips and bills, carpooling, using video conferencing for meetings, and suggesting workplace environmental improvements. Although prior research (e.g., Ardekani et al. 2023; Chin et al. 2015) has examined the role of collaboration in general, or collaboration with suppliers and customers, there is a noticeable gap in understanding how employees' collaboration specifically aids managers in implementing green practices within the hotel industry.

Furthermore, much of the research on green practices implementation has been conducted in developed countries such as Spain, France, Italy, the UK, New Zealand, the USA, and Canada (e.g., Alonso-Almeida et al. 2017; Kang et al. 2012; Prud'homme and Raymond 2013). However, research in some developing countries—such as India—is relatively recent and remains limited in scope.

India's tourism and hospitality sector has experienced significant growth in recent years and is projected to expand at an average annual rate of 6.7% in the coming years (Bag 2023), accounting for approximately 15.34% of total employment by the end of 2029 (WTTC 2022). However, this expansion has coincided with growing environmental concerns, included marked increase in CO2 and other greenhouse emissions, exacerbating the country's environmental degradation (Villanthenkodath et al. 2022). For instance, popular hill stations and mountain tourist destinations in northern India are experiencing substantial waste accumulation from tourism and significant disruption to local wildlife. Therefore, the Indian hotel industry needs to implement green practices on a large scale, being essential to investigate the antecedents driving this adoption.

This study builds upon behavioral literature to highlight key yet underexplored antecedents of implementing green practices, drawing on robust theoretical frameworks such as the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the Norm Activation Model (NAM), and Social Exchange Theory (SET). In doing so, this work offers novel insights and provides managers in developing countries –particularly India—with valuable guidance for crafting effective environmental strategies. These strategies not only aim to reduce the environmental impact of hotel operations but also have the potential to enhance both economic and social performance.

2 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

The Norm Activation Model (NAM), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and Social Exchange Theory (SET) offer valuable theoretical foundations for understanding the relationships among the three factors under consideration. Under the umbrella of NAM, a body of research has highlighted the role of moral motives in encouraging pro-environmental behavior (e.g., Bamberg and Möser 2007; De Groot and Steg 2009), including the implementation of green practices.

Conversely, scholars employing TPB focus on self-interest and the rational assessment of behavioral consequences as primary antecedents of pro-environmental behavior (Lülfs and Hahn 2013). They underline the central role of behavioral intentions as the key antecedent of the behavior itself.

By integrating NAM and TPB, this study incorporates both normative and self-interest based attitudinal antecedents of pro-environmental behavior, offering a more comprehensive explanation of the factors that drive managers to adopt green practices. Moreover, behavior in the corporate sphere highly depends on contextual influences. To address this, SET is included in the theoretical framework for such influences, with a particular focus on individual perceptions of contextual factors or subjective contextual factors (Lülfs and Hahn 2013).

2.1 Norm Activation Model Theory (NAM)

The Norm Activation Model Theory (NAM), introduced by Schwartz (1977), provides a valuable framework for explaining a range of pro-social behaviors, including pro-environmental behavior (De Groot and Steg 2009; Schwartz and Ben David 1976). NAM is founded on two fundamental propositions –the obligation proposition and the activation proposition—which are closely associated with three key concepts: personal norms, awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility.

According to the NAM, altruistic behavior is driven by moral obligation and personal norms, which are themselves shaped by self-expectations and self-behavior (Schwartz 1977). Individuals who hold strong personal norms and a sense of moral obligation to protect the environment are more likely to translate these values into behaviors that support environmental conservation (Penner 2002).

Awareness of consequences pertains to moral and ethical decision-making and is defined as “the extent to which someone is aware of the adverse consequences of not acting pro-socially for others or for other things over values” (Steg and de Groot 2010, 725).

Aspirations of responsibility, meanwhile, relate to perceptions of responsibility for not acting on behalf of society. It involves adopting a defensive position by taking action to fulfill social obligations. NAM assumes that personal norms must be activated to translate them into behavior. This activation can be triggered by recognizing the needs of others, which in turn may trigger an individual's internal values and norms.

Helping behaviors may thus emerge from a sense of moral obligation, shaped by social expectations or empathy with others' suffering. Moreover, such needs can stimulate internal values and norms, fostering helping behaviors even in the absence of external motivators (Saifulina 2020; Schwartz 1977).

2.2 Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen 1991) provides an adequate framework for understanding human behavior by considering attitudes toward that behavior (Kalafatis et al. 1999). TPB posits that an individual's behavior is directly related to the behavioral intention, which is shaped by attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Kautish and Sharma 2020; Lülfs and Hahn 2013).

Personal attitudes refer to the positive or negative feelings associated with achieving a particular objective. An attitude reflects the degree to which a person evaluates a behavior as favorable or unfavorable. According to Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), an individual's attitudes depend on the expected outcomes of the behavior. If the outcome is positive, the attitude toward the behavior is likely to be positive, indicating a positive relationship between attitude and the intention to engage in the behavior. Behavioral intentions serve as motivators, mediating between an individual's attitudes and the actual behavior.

2.3 Social Exchange Theory (SET)

The Social Exchange Theory (SET) is one of the most important frameworks for understanding employees' behavior in the workplace (Blau 1964; Thibaut 1959). According to SET, “social exchange comprises actions contingent on the rewarding reactions of others, which over time provide for mutually and rewarding transactions and relationships” (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005, 890). SET describes reciprocal behaviors in which an organization and its employees exchange mutual trust and commitment to achieve shared goals and objectives, thus fostering high-quality relationships based on reliable work and reciprocal benefits (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005).

Based on SET, employees demonstrate care and commitment to the organization when they perceive reciprocal support from the organization. When employees feel valued and supported by the organization, they are motivated to contribute more toward the firm's success. Such positive treatment by the organization strengthens employees' desire to “give back” in exchange for the support they have received.

2.4 Hypotheses Development

Previous research (e.g., Bohdanowicz 2006; Roberts and Tribe 2008; Sari and Paramastri Hayuning Adi 2023) has examined the factors influencing the implementation of green practices, emphasizing the critical role of managers, who are usually responsible for their execution. Specifically, managers' attitudes toward the environment (MAE) have been identified as a key factor for the successful adoption of green practices (Elsakit and Worthington 2012; Papagiannakis and Lioukas 2012), especially in contexts where environmental legislation and enforcement are lacking, and their influence becomes a primary driver.

Managers' attitudes toward the environment (MAE) are defined as “the degree to which managers consider imperative the active participation of industry in achieving sustainable development” (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006, 1358).

NAM (Schwartz 1977) emphasizes that altruistic behavior, including some pro-environmental behavior, is influenced by moral obligations, personal norms, and values related to the behavior. Moreover, moral principles and values play a critical role in shaping attitudes toward behavior.

When individuals possess moral principles but fail to act in accordance with them, they may experience guilt. To alleviate this feeling, they might develop positive attitudes toward morally appropriate behavior. Attitudes can also emerge as a result of people's values. Specifically, attitudes that reflect concern for the environment can arise from a person's environmental values (Schultz and Zelezny 1999). Because personal norms and values shape attitudes, and NAM suggests that personal and moral obligations are antecedents of altruistic behavior, MAE can serve as an antecedent for altruistic behaviors, such as certain pro-environmental behaviors, including the implementation of green practices.

In this vein, Wesselink et al. (2017), in their study of 479 housing associations' employees, highlighted the role of individual attitudes in promoting pro-environmental behavior. Carballo-Penela and Castromán-Diz (2015) found that managerial attitudes toward the environment are positively related to the implementation of green practices in the service sector. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.Managers' attitudes toward the environment are positively related to the implementation of green practices.

The implementation of green practices can be seen as pro-environmental behavior, which is defined as “actions contributing to environmental conservation, or human activity intended to protect natural resources, or at least reduce environmental deterioration” (Juárez-Nájera et al. 2010, 687). Pro-environmental behavior refers to a range of activities aimed at protecting and preserving nature, minimizing harm to the environment, and enhancing it (Ogiemwonyi et al. 2023; Saifulina 2020; Steg and Vlek 2009). As such, the TPB framework is valuable for understanding the relationship between MAE and the implementation of green practices, with a focus on the intention to perform the behavior.

TPB explains that an individual's positive attitude reinforces his or her intention to act (Ajzen 1991). Intentions are intrinsically motivational and may not be positive in the absence of a favorable attitude toward the behavior (Bagozzi 1992). If the perceived outcome is positive, the attitude will have a positive impact on the intention to perform the behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). The actual behavior is directly shaped by the behavioral intention (Lülfs and Hahn 2013).

Under the framework of TPB, MAE are formed when managers believe that their behavior will produce a positive impact in the environment (e.g., reducing the environmental impact of hotels) (Wyss et al. 2022). Positive attitudes toward the environment lead to intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., the intention to implement green practices), which are direct antecedents of the behavior itself (e.g., the implementation of green practices) (López-Quintela 2024). Consequently, the intention to implement green practices (ITI) will positively mediate the relationship between MAE and IGP. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.The intention to implement green practices positively mediates the relationship between managers' attitudes toward the environment and the implementation of green practices.

Perceived organizational environmental support (POES) is defined as “the specific beliefs held by employees concerning how much the organization values their contributions toward sustainability” (Lamm et al. 2015, 209). POES refers to employees' perceptions and beliefs that organizations (a) will provide them with greater opportunities to manage the environment, (b) will grant them the freedom to make environmental decisions autonomously, and (c) will recognize and value their efforts and contributions to environmental practices (Lamm et al. 2015).

According to SET, when employees and managers feel supported, they are motivated to work for the betterment of the organization, driven by feelings of “payback” in exchange for that support. POES can be viewed as a form of exchange for pro-environmental behavior, such as implementing green practices. If they believe that their efforts to protect the environment are valued by the organization, then managers and employees will be more likely to contribute to achieving its environmental goals (Paillé and Mejía-Morelos 2014).

Previous scholars (e.g., Lamm et al. 2015; Manika et al. 2015; Paillé and Meija-Morelos 2019; Saifulina and Carballo-Penela 2017) have supported the idea that managers and employees are more likely to demonstrate pro-environmental behavior when they receive environmental support and concern from the organization in the form of incentives, rewards, resources, environmental training, and job recognition. In the hospitality sector, Gkorezis (2015) found a positive relationship between POES and pro-environmental behavior using a sample of 102 hotel employees in Greece. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.Perceived organizational environmental support is positively related to the implementation of green practices.

The TPB framework allows for considering ITI to explain the relationship between POES and IGP. According to TPB, perceived behavioral control (PBC) describes how easy or difficult it is for an individual to perform a task or behavior (Inoue and Alfaro-Barrantes 2015). It is influenced by control beliefs, which depend on the opportunities or resources provided by the organization (Ajzen 1991). PBC is a key antecedent strongly associated with behavioral intentions. If managers or employees have the resources and authority to engage in a behavior, a positive intention to perform it will emerge. On the contrary, if there are insufficient opportunities or resources to engage in any behavior, they will not develop behavioral intentions, even if they have positive attitudes and subjective norms (Kalafatis et al. 1999).

As a psychological resource that affects employees' and managers' perceptions about the importance of the environment in their organizations, POES can be a source of PBC, influencing individual perceptions of how easy it is to implement green practices. For instance, POES will provide managers with the behavioral control if they wish to install waste recycling and energy efficiency equipment or purchase solar panels, which will influence their intentions to invest in such initiatives. Because POES increases PBC, it is positively related to behavioral intentions (Garcia et al. 2021; McGuire et al. 2008), which are a direct antecedent of the behavior and mediate between POES and the behavior.

Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.The intention to implement green practices positively mediates the relationship between perceived organizational environmental support and the implementation of green practices.

Previous literature (Aragón-Correa et al. 2013; Johannsdottir and Olafsson 2015; Yang et al. 2017) has underscored the importance of employees' collaboration with managers to effectively implement green practices. Employees' green collaboration (EGC) with managers refers to communication, coordination, and cooperation among employees and managers to initiate green activities (Fadeeva 2005; Lozano 2007).

Green collaboration between managers and employees is a form of teamwork aimed at fulfilling a firm's environmental requirements to improve the organization's environmental conditions (Alherimi et al. 2024). Some examples of green collaboration among employees and managers include following managerial instructions to use environmentally friendly equipment, sharing technical knowledge and experience with co-workers, working together to address environmental issues related to water and energy waste, providing managers with constructive criticism, ideas, and suggestions related to environmental practices at the workplace (Shiach and Virani 2017; Yeboah 2023), or promoting innovation through teamwork and problem-solving behavior (Jankelová et al. 2021; Van de Ven 1986; Widmann et al. 2016).

By sharing information about the necessary actions or distributing resources and information to achieve environmental goals, EGC may help managers and organizations to better identify and evaluate barriers and challenges to implementing green practices (Bonifant et al. 1995). Additionally, EGC may also encourage owners to increase their green investments and help improve the quality of pro-environmental services and, most importantly, enhance the company's positive reputation (Rashid et al. 2012). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5.Employees' green collaboration is positively related to the implementation of green practices.

Based on the TPB framework, EGC can influence managers' intentions to implement green practices (González-Benito and González-Benito 2005) by increasing PBC. Similar to POES, EGC provides managers with various resources (e.g., information, time, or knowledge about environmental challenges).

When managers see that their employees collaborate in green initiatives, they will perceive that it is easier to engage in pro-environmental behaviors (Nguyen et al. 2018; Turkulainen and Ketokivi 2012), thereby increasing PBC. According to TPB, PBC is an antecedent to behavioral intentions, which lead to pro-environmental behaviors, such as the implementation of green practices. Hence, EGC will have a positive effect on ITI, which will mediate the relationship between EGC and IGP.

Considering this, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6.The intention to implement green practices positively mediates the relationship between employees' green collaboration and the implementation of green practices.

Figure 1 shows the proposed conceptual model.

Source: author's own elaboration

.3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Sample and Data Collection

The Indian hospitality sector was selected as our research setting to conduct a survey for data collection and thus develop the empirical study. To reduce the possibility of sources of error, a key informant involved in the decision domain of hotels' strategies and practices was contacted to report on the sustainable and other types of hotels' strategies, results, and other variables related to the profile of each hotel (Hambrick 2007; Huber and Power 1985). Therefore, to ensure data reliability, a convenience sampling method was used, seeking variability in the profile of respondents. Managers from different positions were selected, and a subsection of the questionnaire included questions related to their managers' profile (gender, age, educational level, work experience in hospitality sector, and position level) and hotels' characteristics (hotel group, category/stars, and foreign ownership). This sampling method provides estimates of causal effects comparable to those found in population-based samples (Mullinix et al. 2015).

Data collection was carried out through a survey based on structured questionnaires, which were administered via post and face-to-face interviews with managers. Initially, hotel managers were contacted by mail using an online questionnaire. Subsequently, personal interviews were conducted using printed questionnaires in order to encourage participation and increase the final response rate. Data were collected during July and August 2023, resulting in a final number of 190 valid cases from 84 different Indian hotels, which were used for data analysis and results interpretation.

3.2 Measures

To operationalize the constructs of the study, we relied on previously validated scales from the existing literature, measured on five-point Likert scales for every construct (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), except for ECG (1 = not at all; 5 = to a great extent). Perceived Organization Environmental Support was measured based on Lamm et al. (2015). Managers' Attitude toward the Environment was measured based on Kasim and Ismail (2012) and González-Benito and González-Benito (2006). Employees' Green Collaboration was measured based on Vachon and Klassen (2006). Intention to Implement Green Practices was measured based on Verma and Chandra (2018). Implementation of Green Practices was measured based on Molina-Azorín et al. (2015).

3.3 Data Analysis Approach

The Covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) (maximum-likelihood method) used in this paper is based on measurement and structural model terminology (Hair et al. 2019), first conducting a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to assess measurement and then a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for hypothesis testing, both with IBM SPSS AMOS (version 29). Based on the complexity of the proposed model, the use of CB-SEM to test the proposed hypotheses simultaneously is better suited for confirming or rejecting theories (Hair et al. 2019). We followed the guidelines of Kline (2015) and Hair et al. (2019) to test the direct relationships, and the guidelines of Zhao et al. (2010) and Hayes (2022) for mediation analysis using bootstrapping. In addition, a minimum sample size of 150 is recommended for models with seven constructs or fewer, at least modest communalities, and no underidentified constructs (Hair et al. 2019), conditions that were presented in this research.

4 Analysis and Results

4.1 Preliminary Data Analysis

The obtained sample reported the following profile for managers: gender (male: 64.2%, and female: 35.8%), mean age = 33.1 years old (SD = 6.8), education (Intermediate: 4.2%, Bachelor's degree: 60.5%, Master's degree: 21.6%, and Other: 13.7%), average job experience in the hospitality sector = 8.7 years (SD = 5.2), and managerial position (assistant: 28.4%, middle: 49.5%, and senior: 22.1%). Finally, the hotels in the sample showed the following characteristics: 70.5% were part of a hotel chain, hotel category (one star: 6.9%, two stars: 14.4%, three stars: 30.9%, four stars: 21.3%, and five stars: 26.5%), and 81.6% had local ownership (only 18.4% had foreign ownership).

We examined the possibility of non-response bias by using the guidelines of Armstrong and Overton (1977) and Weiss and Heide (1993) to test for significant differences between early (the first 75% of returned questionnaires) and late respondents (the last 25% of returned questionnaires). Thus, we performed a series of tests with these two groups on (1) several key individual characteristics, such as age (p = 0.286), job experience (p = 0.290), gender (p = 0.773), education (p = 0.494), and job role (p = 0.968), and (2) several key hotel characteristics, such as part of a hotel chain (p = 0.155), star category (p = 0.134), and foreign ownership (p = 0.060), and the results indicated no significant differences between early and late respondents at the 0.05 level, suggesting that non-response bias was not a problem.

In addition, we addressed the possibility of common method bias (CMB) with both ex-ante controls and ex-post analysis. On the one hand, we implemented ex-ante procedural strategies (Kock et al. 2021; Podsakoff et al. 2012): the development of a pretest to ensure the validity and reliability of measures, a survey design aimed at increasing the ability and motivation of respondents (clarity, anonymity, and using simple statements), separation of independent and dependent variables with a mixed order, and random ordering of scale statements. On the other hand, we performed ex-post data collection analysis to test the existence of CMB (Podsakoff et al. 2003): first, a single factor in an exploratory factor analysis did not account for most of the variance (only 16.95%), and second, a new model with all the items loading onto a single factor was re-estimated, with the outcomes not achieving the required values (Chi-square = 4450.26; df = 594; RMSEA = 0.185; CFI = 0.480). Therefore, based on the above, CMB was not a problem in this study.

Finally, several diagnostic tests were performed to assess multicollinearity and endogeneity (see Table 1). On the one hand, there were no correlations between exogenous latent constructs above 0.90, and results for Tolerance and the Variance Inflation Factor fit within suggested values (Tolerance > 0.2; VIF < 5), so there is no issue of multicollinearity (Hair et al. 2019). On the other hand, tests of endogeneity were performed using the 2SLS with the IV technique for each independent variable, being tested individually for each dependent variable (Wooldridge 2019). Thus, the Hausman test for all the exogenous variables was not significant, and the partial R-square and F-statistics were relatively high and significant, suggesting that there is no endogeneity (Daryanto 2020; Wooldridge 2019).

| Correlations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | AVE | TOL | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MAE | 0.853 | 0.727 | 0.342 | 2.926 | ||||

| 2. POES | 0.461 | 0.829 | 0.687 | 0.650 | 1.538 | |||

| 3. EGC | 0.440 | 0.551 | 0.929 | 0.863 | 0.676 | 1.480 | ||

| 4. ITI | 0.760 | 0.379 | 0.404 | 0.943 | 0.889 | 0.375 | 2.670 | |

| 5. IGP | 0.517 | 0.660 | 0.488 | 0.511 | 0.799 | 0.638 | — | — |

| Endogeneity: DV | EV | WH F-stat | WH p | 1st Reg PR-sq | 1st Reg F-stat | 1st Reg p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGP | MAE | 0.006 | 0.940 | 0.268 | 36.372 | 0.000 |

| IGP | POES | 0.110 | 0.741 | 0.438 | 75.514 | 0.000 |

| IGP | EGC | 0.041 | 0.840 | 0.223 | 28.764 | 0.000 |

| IGP | ITI | 0.002 | 0.962 | 0.257 | 34.429 | 0.000 |

| ITI | MAE | 0.073 | 0.788 | 0.616 | 153.652 | 0.000 |

| ITI | POES | 0.322 | 0.571 | 0.141 | 17.044 | 0.000 |

| ITI | EGC | 0.233 | 0.630 | 0.147 | 17.843 | 0.000 |

- Note: Correlations are shown below the diagonal. Bold on the diagonal is the square root of the AVE (average variance extracted).

- Abbreviations: 1st Reg, 2SLS first-stage regression statistics (Partial R-square, F-statistic and p-value); AVE, average variance extracted; DV, Dependent Variable; EGC, Employees' Green Collaboration; EV, Endogenous Variable (Instrumented); IGP: implementation of green practices; ITI, intention to implement green practices; MAE, managers' attitude toward the environment; POES, perceived organization Environmental Support; TOL, tolerance; VIF, variance inflation factor; WH, Durban-Wu–Hausman statistic and p-value.

- Source: Author‘s own elaboration.

4.2 Measurement: Reliability and Validity

The measurement model was based on a comprehensive literature review to select the previously validated scales presented above, which were revised by academic experts in the field, thus ensuring content validity. To assess the measurement model properties (reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity), we performed a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The obtained results from CFA (Table 2) for goodness of fit were within the recommended values (Byrne 2016; Hair et al. 2019): comparative fit index (CFI = 0.950), incremental fit index (IFI = 0.950), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.073), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = 0.056); therefore, the measurement model showed an adequate fit to our data.

| λ (*) | |

|---|---|

| MAE (CRC = 0.930; AVE = 0.727; CA = 0.936) | |

| I would consider establishing an environmental management system (EMS) at my premise | 0.939 |

| I would consider implementation of environmentally friendly practices to be in the top-three priority list in my company policy | 0.877 |

| It is crucial that companies commit themselves to reducing their impact on the natural environment, even if this entails lower productivity | 0.839 |

| Companies do not have the right to damage the natural environment just to satisfy their needs | 0.862 |

| Ensuring environmental protection must be the basis for building the competitive strategy of any company | 0.733 |

| POES (CRC = 0.868; AVE = 0.687; CA = 0.813) | |

| I feel that I am able to behave as sustainably as I want to at the organization where I currently work | 0.800 |

| My organization provides an incentive for me to reduce the use of non-renewable resources | 0.880 |

| My actions toward sustainability are appreciated by my organization | 0.805 |

| EGC (CRC = 0.969; AVE = 0.863; CA = 0.971) | |

| Achieving environmental goals collectively | 0.908 |

| Developing a mutual understanding of responsibilities regarding environmental performance | 0.946 |

| Working together to reduce environmental impact of our activities | 0.959 |

| Conducting joint planning to anticipate and resolve environmental-related problems | 0.921 |

| Making joint decisions about ways to reduce overall environmental impact of our activities | 0.910 |

| ITI (CRC = 0.960; AVE = 0.889; CA = 0.956) | |

| I am willing to implement more green practices in my hotel operations | 0.958 |

| I would prefer green practices implementation along with other operational practices | 0.976 |

| I will make an effort to apply green practices in my hotel operations | 0.893 |

| IGP (CRC = 0.958; AVE = 0.638; CA = 0.958) | |

| Environmental training is offered to all employees and area managers | 0.805 |

| Environmental issues are taken into account when offering the various services available at the hotel | 0.738 |

| Environmental information/data are periodically reviewed and updated | 0.690 |

| An environmental report is prepared in order to disseminate the environmental activities carried out by the hotel | 0.739 |

| The policy of the establishment and its environmental strategy are formally communicated to all its employees | 0.621 |

| The necessary resources are provided in order to carry out environmental improvements in the establishment | 0.866 |

| Procedures are defined and documented for all activities, products and processes which have, or may have if not controlled, a direct or indirect, significant impact on the environment | 0.706 |

| Low environmental impacts products are chosen | 0.856 |

| A suitable disposal/treatment/storage of waste is performed | 0.895 |

| Practices are implemented in order to reduce water consumption | 0.866 |

| Techniques are used to reduce energy consumption | 0.823 |

| Practices are implemented toward lower resource intensity | 0.886 |

| Product re-use/recycling is encouraged | 0.839 |

|

Model fit summary Chi-square = 651.489 (df = 326); χ2/df = 1.998 CFI = 0.950; IFI = 0.950; RMSEA = 0.073; SRMR = 0.056 |

- Note: (*) Standardized loadings.

- Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CA, cronbach alpha; CFI, comparative fit index; CRC, composite reliability coefficient; EGC, employees' green collaboration; IFI, incremental fit index; IGP, implementation of green practices; ITI, intention to implement green practices; MAE, managers' attitude toward the environment; POES, perceived organization environmental support; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

- Source: Author‘s own elaboration.

Moreover, reported values for the composite reliability coefficient (CRC), average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach's alpha (CA) coefficient were higher than the recommended thresholds (CRC > 0.70; AVE > 0.50; CA > 0.70) for every construct, and all items in the measurement models were related to their specific latent variables, with reported individual loadings being large and significant (higher than the recommended value of 0.50), thus showing appropriate levels of reliability and convergent validity (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Bagozzi and Yi 2012).

In addition, as displayed in Table 1, the intercorrelations between any two latent variables in the measurement model did not exceed the square root of the AVE of those constructs, so the discriminant validity was also adequate (Fornell and Larcker 1981). In summary, the measurement model showed appropriate values in terms of reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

4.3 Testing of Hypotheses

To test the proposed hypotheses in our conceptual model, we performed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), and the results are shown in Table 3, reporting values for goodness of fit that were within the recommended thresholds (Byrne 2016; Hair et al. 2019):

| Hypothesis | Independent | Dependent | Standard coefficient | p | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | MAE | IGP | 0.080 | 0.397 | ns |

| Hypothesis 3 | POES | IGP | 0.493 | 0.000 | *** |

| Hypothesis 5 | EGC | IGP | 0.127 | 0.024 | * |

|

Model fit summary Chi-square = 723.527 (df = 327); χ2/df = 2.213 CFI = 0.939; IFI = 0.939; RMSEA = 0.079; SRMR = 0.056 |

|||||

- Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

- Abbreviations: CFI, comparative fit index; EGC, employees' green collaboration; IFI, incremental fit index; IGP, implementation of green practices; ITI, intention to implement green practices; MAE, managers' attitude toward the environment; ns, not significant; POES, perceived organization environmental support; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

- Source: Author‘s own elaboration.

The estimated coefficients regarding the direct effects on the Implementation of Green Practices were significant and positive for Perceived Organization Environmental Support (b = 0.493; p < 0.001) and for Employees' Green Collaboration (b = 0.127; p < 0.05), but it was not significant for Managers' Attitude toward the Environment (b = 0.080; ns). Thus, direct Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 5 were supported, indicating that Perceived Organization Environmental Support and Employees' Green Collaboration are both positively related to the Implementation of Green Practices, but direct Hypothesis 1 was not supported, indicating that Managers' Attitude toward the Environment and the Implementation of Green Practices are not directly related.

Additionally, the estimated coefficients regarding the antecedents of the Intention to Implement Green Practices were significant and positive for Managers' Attitude toward the Environment (b = 0.742; p < 0.001) and for Employees' Green Collaboration (b = 0.103; p < 0.05), but it was not significant for Perceived Organization Environmental Support (b = −0.004; ns). Thus, Managers' Attitude toward the Environment and Employees' Green Collaboration are both positively related to the Intention to Implement Green Practices, but Perceived Organization Environmental Support and the Intention to Implement Green Practices are not related. Finally, the estimated coefficient for the remaining relationship was significant and positive (b = 0.236; p < 0.01), meaning that the Intention to Implement Green Practices and the Implementation of Green Practices are positively related.

Table 4 also shows the analysis of the indirect effects of Managers' Attitude toward the Environment, Perceived Organization Environmental Support, and Employees' Green Collaboration on the Implementation of Green Practices via Intention to Implement Green Practices.

| Hypothesis | Standard coefficient | LCI | UCI | p | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 2: MAE → ITI → IGP | 0.175 | 0.081 | 0.705 | 0.012 | * |

| Hypothesis 4: POES → ITI → IGP | −0.001 | −0.054 | 0.035 | 0.811 | ns |

| Hypothesis 6: EGC → ITI → IGP | 0.024 | −0.001 | 0.092 | 0.120 | ns |

- Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant. Bootstrap confidence intervals derived from 2000 samples (90% level of confidence).

- Abbreviations: EGC, employees' green collaboration; IGP, implementation of green practices; ITI, intention to implement green practices; MAE, managers' attitude toward the environment; POES, perceived organization environmental support.

- Source: Author‘s own elaboration.

The confidence intervals (CI) estimated by bootstrapping showed that, although the total effects on Implementation of Green Practices are positive and significant for the three antecedents of the conceptual model (POES: b = 0.684, CI = 0.465–0.967; MAE: b = 0.451, CI = 0.117–0.677; ECG: b = 0.157, CI = 0.015–0.326), since the zero value is not included in the CI, the indirect effect via Intention to Implement Green Practices is only significant and positive for Managers' Attitude toward the Environment (b = 0.175, CI = 0.081–0.705), being not significant for Perceived Organization Environmental Support (b = −0.001, CI = −0.054 − 0.035) and Employees' Green Collaboration (b = 0.024, CI = −0.001 − 0.092). Thus, mediating Hypothesis 2 was supported, meaning that Managers' Attitude toward the Environment is positively related to Implementation of Green Practices, in this case fully mediated via Intention to Implement Green Practices, since direct effect between both variables is not significant. However, mediating Hypotheses 4 and 6 were not supported, indicating that Perceived Organization Environmental Support and Employees' Green Collaboration are not indirectly related to Implementation of Green Practices via Intention to Implement Green Practices.

5 Discussion

The results of this study are highly relevant to the hotel industry in India. The rapid growth of the tourism sector and the increasing number of tourists in recent years have placed significant pressure on the hospitality industry to adopt green practices. This is particularly pertinent in certain states such as Orissa, Meghalaya, and Indian islands like Andaman and Nicobar, which are popular destinations for eco-tourists.

Our findings underscore the importance of Manager's Attitudes toward the Environment (MAE), Perceived Organizational environmental support (POES), and Employees' green collaboration (EGC) in facilitating the adoption of green practices in Indian hotels. While POES and EGC exert a direct effect on the implementation of green practices, MAE exerts its influence indirectly via the intention to implement green practices (ITI). These results support the majority of our hypotheses and offer both theoretical and practical implications for promoting green practices within the Indian hotel industry.

5.1 Theoretical Implications

Theoretical contributions include the integration of three robust theoretical frameworks –NAM, TPB, and SET—to examine the factors that drive the adoption of green practices. Incorporating these frameworks provides complementary perspectives, enabling a multi-antecedent approach that enhances our understanding of the motivations behind green practices implementation.

By accounting for moral and personal norms (NAM), self-interest (TPB) and contextual influences (SET), this study offers deeper insights into how managerial engagement with green practices may be fostered. On the one hand, our findings indicate that the implementation of green practices may result from managers' self-interest and their assessment of behavioral outcomes, thereby highlighting the role of behavioral intentions as a product of managerial environmental attitudes (Lülfs and Hahn 2013). On the other hand, we demonstrate that green practices may also emerge as a form of reciprocation in response to organizational environmental commitment and values.

Our results reveal that MAE influences the implementation of green practices indirectly through ITI, with ITI fully mediating the relationship between MAE and the Implementation of Green Practices (IGP). Consequently, MAE does not exert a direct influence on IGP, as proposed in Hypothesis 1, but rather affects it indirectly via ITI (Hypothesis 2).

In line with the TPB (Ajzen 1991), we remark that managerial attitudes toward the environment serve as a critical antecedent to their intention to engage in environmentally responsible behavior. According to the TPB framework, self-interest and rational evaluations of behavioral consequences are instrumental in promoting pro-environmental action. Intentions represent the motivational drivers of behavior; thus, the intention to implement green practices plays a pivotal role in their eventual implementation. Without such intentions, MAE alone is insufficient to promote the adoption of green practices, as there is no direct relationship between MAE and IGP.

This conclusion is consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the role of MAE and ITI in promoting green practices within the Indian hospitality sector (e.g., Verma and Chandra 2018). Other studies have also demonstrated the importance of managerial environmental attitudes in encouraging pro-environmental behaviors through behavioral intentions in countries such as Greece (Papagiannakis and Lioukas 2012), as well as across 30 European and North American countries (Wyss et al. 2022).

The findings further reveal a positive relationship between POES and the implementation of green practices. This direct relationship, as proposed in Hypothesis 3, occurs without evidence of an indirect effect of POES on IGP through ITI (Hypothesis 4). While prior research specifically addressing organizational green practices as a distinct form of pro-environmental behavior remains limited, our findings are consistent with earlier studies that demonstrated a positive relationship between POES and various pro-environmental behaviors in Greece (Gkorezis 2015) and Spain (Saifulina and Carballo-Penela 2017).

From a theoretical standpoint, these results support and extend SET, reinforcing its applicability in explaining the relationship between POES and IGP. SET posits that when employees, including managers, perceive organizational support, they are likely to reciprocate through actions that contribute to the organization's success. In this context, our findings suggest that managers reciprocate to POES by implementing green practices—a form of pro-environmental behavior—without the mediation of behavioral intentions. Although we hypothesized that POES would enhance managers' PBC, thereby contributing to the formation of behavioral intentions, our results imply that this may not be the case. The absence of a significant role for ITI suggests that POES may not provide managers with a strong sense of opportunity or autonomy to develop such intentions. In other words, even if POES fosters a sense of PBC, it might not translate into intentions due to a perceived lack of actionable opportunities to implement green practices.

Regarding the relationship between EGC and IGP, our findings support Hypothesis 5, indicating a direct positive relationship between these two constructs. However, we found no evidence of an indirect effect through ITI, as proposed in Hypothesis 6. This outcome contributes to the literature, particularly given the scarcity of studies examining employees' green collaboration with managers. Although some studies emphasize the role of general collaboration between managers and employees, prior empirical research has largely overlooked the role of EGC, focusing instead on other forms of green collaboration, such as with suppliers or customers (Ardekani et al. 2023; Burki et al. 2019; Shah and Soomro 2021; Wong et al. 2021; Yen 2018). There has been a lack of empirical evidence in this specific area.

Only a handful of studies have highlighted how collaboration and cooperation with employees enables managers to recognize, assess, and address environmental challenges, and to implement effective responses (Bonifant et al. 1995; Yang et al. 2017). These works emphasize the importance of manager-employee communication around environmental objectives, the coordination of environmental initiatives, and cooperative action to achieve organizational goals, factors which may facilitate the successful implementation of green practices.

The absence of an indirect effect through ITI in our findings could indicate the need to expand the proposed research model. Additional mediators may be necessary to fully understand the relationship between ECG and IGP. For instance, managers' satisfaction with the green collaboration they experience with employees could potentially explain whether such collaboration results in intentions to behave or not.

5.2 Managerial Implications

Our results offer several practical implications for hotels interested in implementing green practices. Firstly, the findings suggest that organizations can stimulate the adoption of green practices by fostering positive managerial attitudes toward the environment. In line with TPB, such attitudes have a positive effect on the intention to implement the green practices, which in turn leads to their implementation.

This finding underscores the significance of behavioral antecedents in promoting green practices, providing promising avenues for achieving greener hotels. While much of the existing literature has focused on external drivers, such as customer demands regarding the environment (e.g., Alhamad et al. 2023; Cappelli et al. 2022), internal factors, such as managers' attitudes, have received comparatively little attention. Nevertheless, recognizing the importance of attitudinal antecedents is critical and opens up new opportunities for implementing green practices in the hotel industry.

According to TPB, normative beliefs play a key role in the formation of attitudes (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). Normative beliefs refer to an individual's perception of whether his/her specific referents approve of a certain behavior. Therefore, top executives can enhance MAE by demonstrating the organization's commitment to the environment. Concrete measures such as implementing and communicating environmental policies, recognizing and rewarding managers' environmentally responsible behavior, or providing regular updates on the companies' environmental goals and achievements could strengthen managers' normative beliefs about the environment, ultimately contributing to an increase in MAE.

These actions are equally important from the perspective of POES. By actively communicating environmental policies, as well as reaffirming the environment's importance, hotels influence employees' general beliefs about how much the organization values their environmental contributions, i.e., POES.

Accordingly, our findings underscore the relevance of organizational actions that demonstrate commitment to the environment as a foundation for successfully implementing green practices. Firstly, such commitment can positively influence MAE, which subsequently leads to green practices adoption through ITI. Secondly, this commitment can foster repayment behaviors, such as the implementation of green practices by managers.

Providing employees with skills related to collaborative behavior can be valuable for enhancing green collaboration between managers and employees. Although some employees may be willing to collaborate on environmental initiatives, they may lack the necessary skills, particularly in collaboration focused on the environment. Training in core relationship skills, such as appreciating others, participating in purposeful conversations, or resolving conflicts (Gratton and Erickson 2007), can improve collaboration between employees and their managers. More specifically, training focused on how to work with managers to reduce the organization's environmental impact or how to collectively achieve environmental goals can also be highly effective.

In addition to skill development, the human resources department can promote EGC by supporting the creation of informal networks. Informal social activities (e.g., weekend lunches or excursions to natural landscapes) help foster a sense of community, which encourages collaboration in formal activities.

The hotel's top executives could also play a pivotal role in promoting EGC. By serving as role models and actively demonstrating collaborative behavior, they can encourage employees to engage in green collaboration. Moreover, executives can facilitate EGC by investing in appropriate facilities and resources to achieve environmental goals. For example, open workspaces can foster communication between managers and employees (Gratton and Erickson 2007). For instance, sufficient recycling bins can encourage employees to collaborate in recycling activities.

These findings are particularly relevant for hotels in India, where the rapid growth of the hospitality sector and the massive influx of tourists in recent years have resulted in serious environmental impacts. These include increased CO2 emissions, the introduction of invasive species in mountainous and rural regions, water pollution due to an inefficient waste management system, and deteriorating air quality (Ahuja 2022; Raghuvanshi et al. 2006; Rizal and Asokan 2014). While environmental contexts vary –particularly in terms of regulations—this pattern is common in some developing countries experiencing tourism booms, as was the case in Costa Rica in the late nineties (Rivera 2004).

Particularly, the hotel industry in India faces increasing pressure to adopt green practices and minimize environmental harm. Our findings, which highlight the role of internal, or organization-controlled antecedents of green practices (MAE, POES and ECG), provide valuable insights for designing green strategies based on factors that Indian hotels can control.

Information that helps hotels to go green based on internal factors is essential in developing countries. In countries such as India, Costa Rica, Vietnam, and other developing countries, governmental regulation is often less developed than in more developed countries (Hassaine and Abrika 2024; Massoud et al. 2010; Pham et al. 2020; Rivera 2010). Additionally, many domestic tourists may not be in a financial position to pay a premium for environmentally friendly services. As a result, tensions between economic and environmental objectives are strong, especially when local communities suffer the environmental consequences from tourism (Gheewala et al. 2013). However, because some green practices can also yield economic benefits (e.g., savings from energy and water consumption), we provide hotel managers with practical tools that can help them to simultaneously reduce the environmental impact of their activities, improve the economic performance, also benefiting local communities where the hotels are placed (Sharma and Bhat 2023).

Moreover, maintaining skilled employees is a challenge for the Indian hotel industry which experiences high employee turnover rates (Hussain and Soni 2019). The implementation of green practices may contribute to talent retention, especially among younger employees, more aware of the importance of avoiding environmental degradation.

5.3 Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

This research has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the use of a cross-sectional design prevents the examination of causal relationships among the variables studied. Future research should employ longitudinal studies to explore causal relationships.

Second, although our findings on the direct effects of POES and EGC on the implementation of green practices are novel, more research is needed to uncover the underlying mechanisms that drive these relationships. In line with the TPB framework, ITI could be one such mechanism. However, our findings do not provide evidence to support this.

Previous research (e.g., Paillé and Boiral 2013) has pointed to job attitudes, such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment, as antecedents of some pro-environmental behaviors. Under the SET framework, satisfied or committed managers may be more inclined to engage in green practices. It is plausible that managers' perceptions of environmental support and their feelings about employees' green collaboration with them could enhance their satisfaction and commitment, which in turn promotes the implementation of green practices. However, further research is needed to verify this point.

Third, our sample is largely composed of assistant and middle managers, so it is necessary to increase the representation of executive managers. Since the position in the chain of command can determine, for instance, knowledge of hotel policies and commitment to the environment, future research could expand the sample size by including more executive managers. A larger and more balanced sample in terms of managerial positions would also allow for examining the moderating role of managerial position. A bigger sample size would also contribute to increasing the robustness of the findings.

Finally, collecting data from only one country, India, and one sector, the hospitality sector, limits the generalizability of the obtained findings. Future research could test the proposed model in additional countries and sectors. Nevertheless, given the scarcity of studies examining the behavioral antecedents of green practices implementation and the urgent need for Indian hotels to reduce their environmental impact, our findings represent a valuable contribution.

Moreover, the hospitality sector in many developing countries faces similar environmental challenges, meaning that the insights from this study may well apply to other settings. For instance, hotels in India's neighboring countries, such as Pakistan, may also benefit from the findings of this study (Ashraf et al. 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.