A 2015 global update on folic acid-preventable spina bifida and anencephaly

Abstract

Background

Spina bifida and anencephaly are two major neural tube defects. They contribute substantially to perinatal, neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality and life-long disability. To monitor the progress toward the total prevention of folic acid-preventable spina bifida and anencephaly (FAP SBA), we examined their global status in 2015.

Methods

Based on existing data, we modeled the proportion of FAP SBA that are prevented in the year 2015 through mandatory folic acid fortification globally. We included only those countries with mandatory fortification that added at least 1.0 ppm folic acid as a fortificant to wheat and maize flour, and had complete information on coverage. Our model assumed mandatory folic acid fortification at 200 μg/day is fully protective against FAP SBA, and reduces the rate of spina bifida and anencephaly to a minimum of 0.5 per 1000 births.

RESULTS

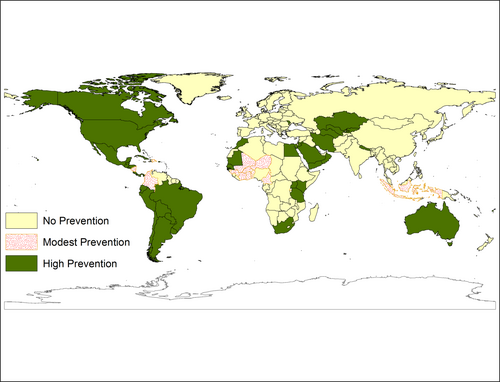

Our estimates show that, in 2015, 13.2% (35,500 of approximately 268,700 global cases) of FAP SBA were prevented in 58 countries through mandatory folic acid fortification of wheat and maize flour. Most countries in Europe, Africa, and Asia were not implementing mandatory fortification with folic acid.

Conclusion

Knowledge that folic acid prevents spina bifida and anencephaly has existed for 25 years, yet only a small fraction of FAP SBA is being prevented worldwide. Several countries still have 5- to 20-fold epidemics of FAP SBA. Implementation of mandatory fortification with folic acid offers governments a proven and rapid way to prevent FAP SBA-associated disability and mortality, and to help achieve health-related Sustainable Development Goals. Birth Defects Research (Part A) 106:520–529, 2016. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Introduction

Spina bifida and anencephaly are two major birth defects that can be largely prevented by folic acid (MRC, 1991; Czeizel and Dudas, 1992; Berry et al., 1999). They are associated with high rates of mortality and disability (Botto et al., 1999; Sutton et al., 2008;). Together, spina bifida and anencephaly contribute to perinatal, neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality (Elwood and Nevin, 1973). The 2013 Global Burden of Disease Mortality and Causes of Death Study underestimates deaths from spina bifida and anencephaly by not including mortality related to stillbirths and induced abortions due to prenatal diagnosis of these conditions (GBD, 2013). Almost all babies born with anencephaly die soon after birth. Babies born with spina bifida have a 10-fold higher risk of death during their childhood compared to those without spina bifida in developed countries (Oakeshott et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011, Kancherla et al., 2014). This risk of death is expected to be much higher in the developing countries where both surgical and medical care to treat spina bifida and its complications are limited. These defects also carry economic and social consequences due to high direct and indirect medical care costs and loss of human potential (Grosse et al., 2005; Ouyang et al., 2007; Grosse et al., 2016).

In 1991, results from a randomized double-blind prevention trial by the Medical Research Council's Vitamin Study Group provided unequivocal evidence that folic acid prevents the majority of spina bifida and anencephaly (MRC, 1991). By 1998, the United States implemented mandatory folic acid fortification of wheat flour and maize (excluding corn masa) flour to prevent folic acid-preventable spina bifida and anencephaly (FAP SBA). A recent analysis has shown that approximately 1300 new cases of spina bifida and anencephaly have been prevented each year in the United States during the postfortification period (Williams et al., 2015). Grosse et al. (2016) reported that the number of spina bifida cases that were prevented by the folic acid fortification mandate in the United States resulted in an annual total direct cost savings of $607 million (not including caregiver time costs), with a cost-benefit ratio of approximately $150 saved on averted medical care costs for every dollar spent on fortification. Several other countries (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Iran, Jordan, South Africa) that mandated folic acid fortification reported reductions in birth prevalence and/or increase in health care savings after successful fortification interventions (Castillo-Lancellotti et al., 2013). According to the Food Fortification Initiative (previously known as the Flour Fortification Initiative), more than 100 countries have yet to implement this safe and cost-effective policy to prevent FAP SBA (accessed at: http://www.ffinetwork.org/global_progress/index.php).

Central to any disease prevention effort is surveillance and periodic quantification of progress. Historically, small pox was eradicated on a similar principle. Monitoring global fortification status can guide prevention efforts for FAP SBA. We examined the 2015 status of the global prevention of FAP SBA achieved through mandatory folic acid fortification of wheat and maize flour. The current study is next in the series of our global updates on FAP SBA (Bell and Oakley, 2006, 2009; Youngblood et al., 2013).

Materials and Methods

We obtained the annual number of births within each country from the latest United Nations database of births (Year 2013) (accessed at: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/SOWC_2015_Summary_and_Tables.pdf). Country-specific modeled estimates of the birth prevalence of neural tube defects (which are majorly comprised of spina bifida and anencephaly) were abstracted from the latest March of Dimes Global Report on Birth Defects (Christianson and Modell, 2006). Due to paucity of country-specific data on prevalence of birth defects, especially in low- and middle-income countries, the March of Dimes extrapolated data from several sources, pooled it, and used the pooled values to model prevalence estimates for birth defects. This was the first time such a global estimate of neural tube defects had been attempted. These estimates, although not recent or precise, allow a general comparison of spina bifida and anencephaly prevalence at birth across different countries.

Postfortification birth prevalence of spina bifida and anencephaly in the United States is estimated to be approximately 0.5 per 1000 live births (Williams et al., 2015). This prevalence estimate has remained stable since fortification and was assumed as a baseline or an achievable prevalence through mandatory fortification in our analysis. Similar postfortification prevalence has been shown in other countries (De Wals et al., 2008; Sayed et al., 2008; Cortes et al., 2012). Additionally, modeled data by Crider et al. (2014) showed that an optimal achievable prevention of spina bifida and anencephaly through folic acid fortification should yield a lowest prevalence of approximately 0.5 to 0.6 per 1000 births. Additionally, two case–control studies after folic acid fortification in the United States failed to demonstrate a protective effect of extra folic acid in multivitamin supplement pills on the risk of neural tube defects, which is consistent with the current amount of folic acid consumed as a result of mandatory folic acid fortification as being sufficient in the United States for near complete if not complete prevention of FAP SBA (Mosley et al., 2009; Ahrens et al., 2011). It has been estimated that mandatory folic acid fortification alone adds approximately 138 μg/day of folic acid to the diets of almost all men and women in the United States (Daly et al., 1995, 1997; Berry et al., 2007; Mosley et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2010). Based on the above evidence, we assumed in our analysis that mandatory folic acid fortification at 200 µg a day would prevent all FAP SBA and lower the rate of spina bifida and anencephaly to a minimum of 0.5 per 1000 births.

The estimated country-specific annual frequency of spina bifida and anencephaly was calculated as the product of 2013 estimated births and the prevalence of neural tube defects (as mentioned earlier, comprised primarily of spina bifida and anencephaly) from March of Dimes report. The annual number of FAP SBA per country was then calculated as the difference in number of cases occurring based on a country's prefortification prevalence rate and subtracting from it the number of cases that would be expected at an achievable prevalence rate during postfortification period (at 0.5 per 1000 births). For example, if a country had a prevalence of 2.5 per 1000 births (prefortification) in the March of Dimes report, we first calculated the number of cases that would occur at this prefortification rate, and subtracted from that the number of cases that would occur at an achievable postfortification prevalence of 0.5 per 1000 births.

The country-specific levels of current folic acid fortification were measured as amount of folic acid (in μg/g) for wheat and maize flour. Some countries require a specific amount while others have specified an acceptable range. When data were presented as a range, the mean was used as a point estimate for the analysis. All information on current folic acid fortification was derived from the Food Fortification Initiative database (accessed at: http://www.ffinetwork.org/country_profiles/index.php). The Food Fortification Initiative abstracts these data from country legislation and flour standards. For our analysis, we examined countries which had a mandatory folic acid fortification policy for wheat flour alone, or in combination with maize flour, during the year 2015.

The daily estimated amount of fortified wheat and maize flour (measured in grams) available per capita was abstracted, and used as a proxy for per capita consumption, on a country-specific basis using data from the 2011 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Food Balance Sheets (accessed at: http://faostat3.fao.org/faostat-gateway/go/to/download/FB/*/E). Estimates were decreased by 10% to account for wastage (Parfitt et al., 2010). The total folic acid consumed from daily intake of fortified wheat and maize was calculated as the product of folic acid fortification level and the daily amount of fortified flour intake.

Country-specific program coverage was also abstracted based on data from the Food Fortification Initiative (accessed at: http://www.ffinetwork.org/global_progress/index.php). It was estimated as a product of two variables: (1) percentage of a country's flour (wheat or maize) that is produced in large scale industrial mills, and representing the flour that has the potential for fortification; and (2) percentage of a country's industrial flour (wheat or maize) that is fortified with folic acid. The percentage of industrially produced flour that was fortified in each country was used as a proxy of the percentage of people with access to fortified flour. Information regarding the above two variables was provided to the Food Fortification Initiative by the organization's regional staff as well as partners in local industry and government (accessed at: http://www.ffinetwork.org/about/stay_informed/releases/2014Review.html). Program coverage data for wheat was complete for all 81 countries that mandated folic acid fortification of wheat, but available for only 5 of the 12 countries that mandated for maize. Because of this limitation, we extrapolated coverage values for maize to be same as that reported for wheat.

We used a prevention model to estimate the number of FAP SBA through daily consumption of fortified wheat and maize flour. This model estimated the country-specific number of FAP SBA as a product of: (1) the annual number of FAP SBA cases in a country, (2), the proportion of FAP SBA that can be prevented based on the level of total folic acid consumption from fortification (μg/day), and (3) the program coverage (%). We considered the proportion of FAP SBA that can be prevented is 50% for populations consuming 100 μg per day (range, 20–150 μg/day) of folic acid from fortified flour daily; and 100% for countries with 200 μg per day (≥ 151 μg/day) or more.

The global proportion of FAP SBA currently prevented by mandatory folic acid fortification was estimated as the quotient of the total FAP SBA prevented with current fortification levels and coverage in countries that have mandatory fortification of wheat and maize flour, and the total number of FAP SBA from all countries assuming no fortification. The total number of FAP SBA that would occur globally was calculated as the difference of global neural tube defects birth prevalence rate provided by the March of Dimes (2.4 per 1000 live births) and the baseline postfortification prevalence at 0.5 per 1000 live births, which equaled to 1.9 per 1000 live births, or 268,739 cases worldwide. The global number of total live births were based on 2013 United Nations estimates (N = 138,740,000). The overall percent of FAPSBA cases that are currently being prevented through folic acid fortification were estimated as the quotient of cases that are currently prevented through mandatory fortification divided by total cases of FAP SBA that are occurring globally.

Results

Based on the 2015 Food Fortification Initiative data, 81 countries were reported to be fortifying wheat flour alone or in combination with maize flour (n = 12) on a mandatory basis; however, 5 of these countries did not mandate folic acid in their food fortificants (United Kingdom, Venezuela, Philippines, Nigeria [until October, 2015], and Congo) and were not included in our analysis. In October 2015, Nigeria included folic acid in its fortification decree. In addition to the 81 countries, Burundi and Malawi passed legislations in the mid-year 2015 to implement mandatory folic acid fortification, and allowed until year 2016 to achieve compliance. Thus, Nigeria, Burundi, and Malawi were not included in our current analysis, but will be considered after achieving compliance in our future analysis. Data on current folic acid fortification level (ppm) or program coverage (percent) were missing for 17 countries (Antigua and Barbados, Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Iraq, Jamaica, Liberia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadine, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Suriname, Trinidad, and Tobago). These 17 countries were also excluded in our analysis. Finally, Kosovo fortifies wheat with folic acid at 1.5 ppm, but could not be included in our analysis because prefortification neural tube defect rate and the amount of wheat flour consumed were unavailable.

Thus, only 58 countries met our study eligibility criteria for having current mandatory folic acid fortification policy and complete data on variables that were used to determine country-specific frequency of FAP SBA. All 58 countries mandate wheat flour fortification, and of these, 10 countries also mandate maize flour fortification (Table 1). Specifically, all of the 58 countries added at least 1.0 ppm folic acid as a fortificant to wheat and maize flour and had information of coverage. Overall, 20 countries in Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Cote d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda), 14 in Asia (Bahrain, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Oman, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Yemen), 2 in Australasia (Australia, Fiji), 1 in Europe (Republic of Moldova), 21 in the Americas and the Caribbean (Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, United States, Uruguay) were implementing mandatory folic acid fortification in the year 2015. Most countries in Africa and Asia (including Nigeria, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China, which have a high burden of FAP SBA) were not implementing mandatory folic acid fortification in 2015.

| Country | Annual birthsa | NTD (majorly SBA) birth prevalence per 1000 live births pre-fortificationb | Annual FAP SBAc | Folic acid fortification level, ppmd | Daily grams of fortified flour consumede (g/capita/day) | Total folic acid consumption from fortification, μg/dayf | Program coverage percentg |

MODEL Annual FAP SBA preventedh |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Maize | Wheat | Maize | |||||||

| Argentina | 694,000 | 2.1 | 1110 | 2.2 | -- | 283 | -- | 560.3 | 99 | 1099 |

| Australia | 308,000 | 0.6 | 31 | 2.5 | -- | 191 | -- | 429.8 | 67 | 21 |

| Bahraini | 20,000 | 1.2 | 14 | 1.5 | -- | 248 | -- | 334.8 | 90 | 13 |

| Belize | 8,000 | 2.5 | 16 | 1.8 | -- | 168 | -- | 272.2 | 100 | 16 |

| Benin | 376,000 | 2.7 | 827 | 2.6 | -- | 24 | -- | 56.2 | 90 | 372 |

| Bolivia | 275,000 | 2 | 413 | 1.5 | -- | 148 | -- | 199.8 | 80 | 330 |

| Brazil | 2,995,000 | 1.9 | 4193 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 146 | 67 | 287.6 | 100 | 4193 |

| Burkina Faso | 693,000 | 2.7 | 1525 | 2.6 | -- | 24 | -- | 56.2 | 100 | 762 |

| Cameroon | 831,000 | 2 | 1247 | 2.6 | -- | 51 | -- | 119.3 | 98 | 611 |

| Canada | 396,000 | 1.6 | 436 | 1.5 | -- | 191 | -- | 257.9 | 90 | 392 |

| Cape Verde | 10,000 | 2.7 | 22 | 2.6 | -- | 101 | -- | 236.3 | 98 | 22 |

| Chile | 245,000 | 1.9 | 343 | 1.8 | -- | 295 | -- | 477.9 | 100 | 343 |

| Colombia | 907,000 | 2 | 1361 | 1.5 | -- | 90 | -- | 124.7 | 100 | 680 |

| Costa Rica | 74,000 | 0.5 | 0 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 110 | 29 | 212.1 | 95 | -- |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 745,000 | 2.7 | 1639 | 2.6 | -- | 55 | -- | 128.7 | 90 | 738 |

| Cuba | 107,000 | 1.8 | 139 | 1.9 | -- | 142 | -- | 242.8 | 100 | 139 |

| Djibouti | 24,000 | 2.2 | 41 | 1.3 | -- | 318 | -- | 372.1 | 95 | 39 |

| Dominican Republic | 217,000 | 1.8 | 282 | 1.8 | -- | 83 | -- | 134.5 | 100 | 141 |

| Ecuador | 328,000 | 2 | 492 | 1.7 | -- | 108 | -- | 165.2 | 100 | 492 |

| Egypt | 1,901,000 | 2.2 | 3232 | 1.5 | -- | 400 | -- | 540 | 55 | 1777 |

| El Salvador | 128,000 | 2.5 | 256 | 1 | 1 | 77 | 199 | 248.4 | 100 | 256 |

| Fiji | 18,000 | 1.5 | 18 | 1.6 | -- | 238 | -- | 342.7 | 99 | 18 |

| Ghana | 800,000 | 2.7 | 1760 | 2.1 | -- | 51 | -- | 96.4 | 90 | 792 |

| Guatemala | 480,000 | 2.5 | 960 | 1.8 | -- | 97.0 | -- | 157.1 | 98 | 941 |

| Guinea | 394,000 | 2.7 | 867 | 1.4 | -- | 44.0 | -- | 55.4 | 90 | 390 |

| Honduras | 209,000 | 2.5 | 418 | 1.8 | -- | 101.0 | -- | 163.6 | 100 | 418 |

| Indonesia | 4,691,000 | 0.7 | 938 | 2 | -- | 64.0 | -- | 115.2 | 100 | 469 |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 1,455,000 | 2 | 2183 | 1.5 | -- | 417 | -- | 563 | 100 | 2183 |

| Jordan | 193,000 | 3.3 | 540 | 1 | -- | 392 | -- | 352.8 | 100 | 540 |

| Kazakhstan | 337,000 | 2 | 506 | 1.5 | -- | 259.0 | -- | 349.7 | 33 | 167 |

| Kenya | 1,550,000 | 1.3 | 1240 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 93.0 | 211 | 410.4 | 100 | 1240 |

| Kuwait | 69,000 | 1.2 | 48 | 1.5 | -- | 269 | -- | 363.2 | 100 | 48 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 151,000 | 2 | 227 | 1.5 | -- | 378 | -- | 510.3 | 6 | 14 |

| Mali | 723,000 | 2.7 | 1591 | 2.6 | -- | 31 | -- | 72.5 | 62 | 493 |

| Mauritania | 133,000 | 2.7 | 293 | 2.6 | -- | 270 | -- | 631.8 | 0 | -- |

| Mexico | 2,252,000 | 2.5 | 4504 | 2 | 2 | 92 | 317 | 736.2 | 55 | 2477 |

| Morocco | 750,000 | 2.2 | 1275 | 1.5 | -- | 486 | -- | 656.1 | 72 | 918 |

| Nepal | 584,000 | 4.7 | 2453 | 1.5 | -- | 124 | -- | 167.4 | 15 | 368 |

| Nicaragua | 138,000 | 2.5 | 276 | 1.8 | -- | 72 | -- | 116.6 | 100 | 138 |

| Niger | 890,000 | 2.7 | 1958 | 2.6 | -- | 10 | -- | 23.4 | 0 | -- |

| Omani | 74,000 | 1.2 | 52 | 1.8 | -- | 248 | -- | 390.6 | 89 | 46 |

| Palestine (State of) | 132,000 | 5.5 | 660 | 1.8 | -- | 320 | -- | 504 | 100 | 660 |

| Panama | 75,000 | 2.5 | 150 | 1.8 | -- | 103 | -- | 166.9 | 10 | 15 |

| Paraguay | 162,000 | 2 | 243 | 3.0 | -- | 91 | -- | 245.7 | 80 | 194 |

| Peru | 599,000 | 2 | 899 | 1.2 | -- | 149 | -- | 160.9 | 90 | 809 |

| Republic of Moldova | 42,000 | 2.7 | 92 | 1.4 | -- | 150 | -- | 189 | 0 | -- |

| Rwanda | 414,000 | 1.3 | 331 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 38 | 39 | 113.9 | 1 | 2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 561,000 | 1.2 | 393 | 1.5 | -- | 248 | -- | 334.8 | 100 | 393 |

| Senegal | 534,000 | 2.7 | 1175 | 2.6 | -- | 90 | -- | 210.6 | 96 | 1128 |

| South Africa | 1,099,000 | 2.3 | 1978 | 2 | 2 | 166 | 275 | 793.8 | 59 | 1167 |

| Tanzania (United Republic of) | 1,913,000 | 1.3 | 1530 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 42 | 156 | 267.3 | 95 | 1454 |

| Togo | 248,000 | 2.7 | 546 | 2.6 | -- | 32 | -- | 74.9 | 100 | 273 |

| Turkmenistan | 112,000 | 2 | 168 | 1.5 | -- | 515 | -- | 695.3 | 95 | 160 |

| Uganda | 1,626,000 | 1.3 | 1301 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 31 | 111 | 174.9 | 37 | 481 |

| United Statesj | 4,230,000 | 1.4 | 3807 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 218 | 34 | 331.3 | 90 | 3426 |

| Uruguay | 49,000 | 1 | 25 | 2.4 | -- | 310 | -- | 669.6 | 100 | 25 |

| Uzbekistan | 622,000 | 2 | 933 | 1.5 | -- | 467 | -- | 630.5 | 80 | 746 |

| Yemen | 760,000 | 1.2 | 532 | 1.6 | -- | 312 | -- | 449.3 | 90 | 479 |

| TOTAL | 35,506 | |||||||||

| Prevention percent | 13.2% | |||||||||

- Kosovo fortifies wheat flour at 1.5 ppm, but is not included because pre-fortification the neural tube defect birth prevalence and amount of flour consumed were unavailable. The Solomon Islands fortify wheat flour at 2 ppm; but are not presented in the table because program coverage was unavailable.

- a 2013 United Nations estimates (available at: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/SOWC_2015_Summary_and_Tables.pdf; accessed on 1/27/2016).

- b Christianson et al., 2006.

- c Calculated at a base prevalence of 0.5 per 1000 live births.

- d Country-specific levels of current folic acid fortification were measured as amount of folic acid in μg/g for wheat and maize flour abstracted from Food Fortification Initiative database (http://www.ffinetwork.org/country_profiles/index.php).

- e From Food Balance Sheets (FAO, 2009). FAO provides availability data that have been used as a proxy for consumption in our analysis.

- f Daily μg folic acid consumed is calculated from the fortification level × daily grams consumed, totaled across wheat and maize flour.

- g Country-specific program coverage was abstracted from the Food Fortification Initiative (http://www.ffinetwork.org/global_progress/index.php) calculated as percentage of a country's flour (wheat or maize) that is produced in large scale industrial mills, and representing the flour that has the potential for fortification × percentage of a country's industrial flour (wheat or maize) that is fortified with folic acid.

- h Number of NTDs prevented by wheat (with or without maize) flour fortification, calculated as product of folic acid-preventable NTD estimate × prevention percentage × program coverage.

- i Used estimate of wheat flour consumption from Saudi Arabia.

- j Estimates of FAP SBA in Puerto Rico and United States Virgin Islands are included in the estimate for the United States. Yang et al. (2010) published the amount of folic acid obtained through fortified foods alone in the United States to be 138 μg per day.

- FAP SBA, folic acid-preventable spina bifida and anencephaly; NTD, neural tube defects; ppm, parts per million; SBA, spina bifida and anencephaly.

According to the March of Dimes Global Report on Birth Defects, the average global birth prevalence of spina bifida and anencephaly was 2.4 per 1000 live births. The United Nations, in their State of the World's Children Report, estimated that there were 138,740,000 births during the year 2013. At the aforementioned birth prevalence rate of 2.4 per 1000 live births, we can expect approximately 338,109 cases of spina bifida and anencephaly globally annually. If all the countries implemented interventions to prevent FAPSBA, we would be able to prevent 268,739 cases of spina bifida and anencephaly (i.e., at a baseline prevalence of 0.5 per 1000 births globally). However, we found that only 58 of the countries with mandatory folic acid fortification had complete data on folic acid fortificant levels and coverage during the year 2015 and thus were included in the analysis (Table 1). In these 58 countries, our prevention model (assuming 200 μg/day of folic acid for total protection from spina bifida and anencephaly) estimated 35,506 cases of spina bifida and anencephaly were prevented in 2015. This accounts for a prevention percent of 13.2% of all cases of FAP SBA worldwide.

Figure 1 provides the status of prevention of FAP SBA among countries globally. A majority of countries in North, Central, South America and the Caribbean, and Australasia shows a high prevention of FAP SBA because of their mandatory folic acid fortification policies. The map also tracks countries with modest prevention, counted as less than 100% prevention. Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Colombia, Cote d'Ivoire, Dominican Republic, Ghana, Guinea, Indonesia, Mali, Nicaragua, Niger, Rwanda, and Togo currently have modest prevention. Overall, Europe and most countries in Africa and Asia were categorized as not preventing FAP SBA through mandatory folic acid fortification programs.

Discussion

We have achieved only 13% of prevention of FAP SBA globally in the year 2015. Our analysis shows that only 58 countries, with fortification data available, are implementing mandatory fortification programs with at least 1.0 μg/g of folic acid. There is an urgent need to scale up the pace of prevention of FAP SBA through mandatory folic acid fortification. The scale up should specifically target countries in Africa and Asia that have a high prevalence of FAP SBA. We also acknowledge that legislation of folic acid fortification should be followed by recurrent market and biomarker monitoring to gain a complete understanding of compliance and uptake by at-risk populations. Successful interventions will not only prevent FAP SBA, but will also contribute to reducing perinatal, neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality associated with FAP SBA.

We have stressed both in the current study as well as our previous updates of tracking FAP SBA prevention (Bell and Oakley, 2006, 2009; Youngblood et al., 2013) that our estimates are based on limited resources and best available evidence. There is a clear need for improving reporting of both birth prevalence of FAP SBA and folic acid fortification variables such as coverage and uptake of fortified foods by the target population. Our new model was improved in relation to our previous models with latest available evidence. Further improvements in assessing global prevention of FAP SBA are possible based on recent developments in red blood cell folate surveillance to predict the population prevalence of spina bifida and anencephaly; discussed elsewhere (Oakley and Kancherla, 2016).

Our 2015 FAP SBA prevention estimate based on 200 μg/day folic acid as a protective factor, is lower than the estimate presented in 2012 (13% vs. 25%, respectively) (Youngblood et al., 2013). This difference is partly due to a change in the data source that was used between 2012 and 2015. For the year 2015, we used program coverage from the Food Fortification Initiative database (http://www.ffinetwork.org/). The exact method of how the program coverage was estimated has been discussed in detail in our study methods.

The World Health Organization has suggested that there would be full or near full prevention of FAP SBA if women in a population have red blood cell folates above a concentration of 400 ng/ml (906 nmol/L) (WHO, 2015). This established threshold of red blood cell folate in the population can help determine the burden of neural tube defects in the country without having to implement expensive and time-intensive birth defects surveillance studies (Crider et al., 2014). Folate surveys will provide reliable data upon which to estimate country-specific and global prevention of FAP SBA.

There are some limitations in our analysis. We understand that our estimates are based on older and modeled data, and may not accurately represent the prevalence of FAP SBA in each of the countries included in our analysis. Due to limited reporting, program coverage data for maize had to be extrapolated from wheat coverage information. According to the FFI, in the majority of regions worldwide large industrial mills produce wheat flour, while maize flour production occurs at a smaller scale. Thus, assuming that the coverage is same between wheat and maize flours can be a limitation in our analysis, and can be improved in the future with availability of additional data. Additionally, dietary practices vary in individual countries, and fortification may not reach all of their populations. Study findings provide a crude estimate of the level and pace of global prevention trends of FAP SBA, but it is still the best benchmark for global progress on prevention of FAP SBA until countries develop better surveillance and evaluation of fortification strategies.

The March of Dimes and the Global Burden of Disease estimates on the prevalence and mortality of spina bifida and anencephaly systematically underestimate their burden by excluding stillbirths associated with these conditions (Elwood and Nevin, 1973). Furthermore, most affected fetuses that are electively terminated after a prenatal diagnosis are not included in the above estimates. Thus, our findings on the current prevention level of spina bifida and anencephaly, which is based on live births alone, undercounts the true prevention through fortification with folic acid. As the surveillance of birth defects is improving to encompass all birth outcomes, we expect to increase the accuracy of our prevention estimates in the future.

For almost 25 years, we have had the scientific basis for the total prevention of FAP SBA, and we are preventing only approximately 13% of what can be prevented. Countries in Asia and Africa which have 5- to 10-fold epidemics of FAP SBA compared with countries in North and South America with mandatory folic acid fortification, show a large geographic variation in the prevalence of these major birth defects and opportunities for prevention. Mandatory folic acid fortification is a proven intervention (Bhutta et al., 2014) and has been shown to be a highly effective, safe, easy to implement, and has a high cost-benefit ratio (1:150 in the United States). The resolution from the Teratology Society in 2014 recommended that: “All governments institute mandatory folic acid fortification of a centrally produced food (such as, but not limited to, wheat flour, corn flour or meal, rice and maize flour, or meal) to provide almost all adults with at least an additional 150 μg of folic acid per day (Smith and Lau, 2015).”

We conclude from our study that there is an urgent need for all countries to require folic acid fortification of centrally processed and widely eaten staple foods. When implemented and monitored successfully, folic acid fortification is proven to make significant a contribution toward preventing FAP SBA and reducing country-specific and global rates of under-five mortality and disability associated with these birth defects, thus allowing us to achieve health-related Sustainable Development Goals. While obvious, we note that every day that mandatory folic acid fortification is not implemented in a country, we will continue to have not only unnecessary FAP SBA, but also folate deficiency anemia (Odewole et al., 2013). Additionally, a recent report of a large randomized controlled trial from China strongly suggests that benefits of mandatory folic acid fortification likely includes prevention of an important proportion of first ischemic strokes (Huo et al., 2015; Stampher and Willett, 2015). Mandatory folic acid fortification will not only improve the health of children and adults, but will lead to significant savings in healthcare expenditures that can be re-directed for other priorities.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sophie's Voice Foundation and the Rich Foundation for supporting this research in part through their unrestricted gifts. We also thank Timothy Nielson (graduate student at Emory University Rollins School of Public Health) for his assistance in providing country-specific data on folic acid fortification from the Food Fortification Initiative database. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. Dr. Godfrey P. Oakley Jr. is a co-inventor (while at CDC, compensation is under the regulations of CDC) of a patent that covers adding folic acid to contraceptive pills and he has been a consultant to Ortho McNeil on this issue.