A geospatial and archaeological investigation of an African–American cemetery in Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

Abstract

Oberlin Cemetery, located near downtown Raleigh, North Carolina, USA, was founded in 1873 following the American Civil War (1861–1865). This 3.2 ac (~1.29 ha) parcel of land served as the main cemetery for the people of Oberlin Village—the largest freedmen's community in Wake County. Today, descendants of the village founders and other neighbourhood residents, organized as the Friends of Oberlin Village (FOV), are preserving this community landmark and working to have its historical significance recognized. In support of these efforts, terrestrial laser scanning, global-positioning-system-enabled pedestrian and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys were conducted during the winter and summer of 2016. We inventoried 276 formal grave markers identifying 221 individuals, 296 elongate depressions without a formal marker interpreted as sunken graves, and 130 fieldstones interpreted as burial markers, resulting in an estimate of 517-to-660 persons interred within the cemetery. The GPR survey supported the interpretation of topographic depressions as sunken graves; however, the undulating topography, as well as the density of trees and shrubs, limited this survey to ~12% of the site. Based on the birth dates listed on monuments, ~23% of these persons were born before the end of the Civil War. Death dates show the community's continued use of the cemetery throughout the early 1970s and less frequent use after that, with the most recent burials in 2009. A comparison with a 2012 inventory of monuments within Oberlin Cemetery suggests that ~3% of the markers were lost or displaced in 4 years, highlighting the importance of survey and preservation efforts. This work contributed to the FOV's successful nomination of the cemetery to the US National Register of Historic Places and was used to support several grants received for its preservation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cemeteries in historic communities are valuable resources offering insight into the temporal development of neighbourhoods (Cannon, 1989; Jamieson, 1995; Little, 1998; McGuire, 1988; Pearson, 1993; Tarlow, 1999; Vlach, 1978). However, their preservation typically requires community engagement, and the task of maintaining these sites is often left to local governments and civic groups that may include descendants, neighborhood residents and other volunteers. In support of applications for local historical landmark status, as well as educational and outreach initiatives, communities have often worked with academic researchers and contractors to collect base-level information on burial records, catalogue the distribution of gravestones and other material culture and identify otherwise unmarked graves within historic cemeteries (Barton et al., 2023; González-Tennant, 2016; Liebens, 2003; Rainville, 2008, 2009).

Cemeteries throughout the United States reveal a rich necrogeography that reflects the varying traditions and life-histories of its people (Baugher & Veit, 2014; Jeane, 1978; Jordan, 1982; Kniffen, 1967; Warner, 1959; Young, 1960). Many archaeological studies of historical cemeteries have focused on traditionally segregated communities whose histories often remain poorly documented. These include the historic cemeteries of indigenous populations (Mainfort, 1985; Panich, 2015; Rodning, 2011), immigrant groups (Lenik & Gibbs, 2000; Moody & Good, 2002; Salazar, 2009) and enslaved or previously enslaved peoples (Condon et al., 1998; Honerkamp & Crook, 2012; Jamieson, 1995; Wilson & Cabak, 2004).

Archaeological studies at historic African–American cemeteries have been a particularly vital component of efforts to uncover and document the rich heritage of these communities. In 1991, during excavation for a planned federal office building in New York City, a cemetery was uncovered containing the remains of free and enslaved Africans who lived and labored in colonial New York. The remains of 419 individuals and more than 500 artefacts were recovered from the site before mitigation efforts were halted, with subsequent research suggesting that ~15 000 individuals were buried on these grounds (Perry et al., 2009a, 2009b). This discovery and surrounding controversy over the lack of community involvement ignited widespread interest in the site. By 1993, the New York City Historic Landmarks Preservation Commission recognized the site as a historic landmark and a federal steering committee formed to plan for the construction of a memorial (LaRoche, 2012, 649–52). In 2006, the African Burial Ground National Monument was established on this site to ‘promote understanding of related resources, encourage continuing research, and present interpretive opportunities and programs for visitors to better understand and honor the culture and vital contributions of generations of African and Americans of African descent to our Nation’ (Presidential Proclamation 7984, 2006). Reflecting on the importance of the cemetery, the controversy and its resolution, archaeologist Cheryl LaRoche (2012, 649) observed that ‘its discovery redefined and forever changed the relationship between archaeologists and the publics they serve.’ Discoveries like those in New York continue to unfold nationwide (Degollado, 2020; Guzzo, 2022; Mooney & Morrell, 2013).

Following the American Civil War (1861–1865), African–American cemeteries created during or maintained through the Reconstruction Era (1865–1877) document the history of free and emancipated people as they struggled to build new communities. Despite these gains, Jim Crow Era (the 1870s to 1950s) laws further institutionalized racial divisions within the United States and perpetuated the existence of segregated neighborhoods and cemeteries. Over time, with redevelopment and shifting demographics in many areas, those cemeteries that remain may provide the only visible link to the historical identity of a neighborhood—revealing civic histories, kinship structures, religious practices, cultural beliefs and racialized experiences of its founding residents (Dunnavant, 2017; La Roche & Blakey, 1997; LaRoche, 2012; Rainville, 2009; Sattenspiel & Stoops, 2010; Vlach, 1991).

Archaeological research on Reconstruction Era African–American cemeteries gained prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with extensive studies investigating the Cedar Grove Cemetery in Arkansas (Rose, 1985) and the black section of the Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, Georgia (Blakely & Beck, 1982). The Freedman's Cemetery in Dallas (1869–1907) remains the largest example of excavation at an African–American cemetery, with 1157 individuals exhumed due to the demands of highway construction in the early 1990s (Condon et al., 1998; Davidson, 1999; Peter et al., 2000). Subsequent archaeology research at these and other sites have focused on the documentation of burials (Cox & Day, 2011; Ozga et al., 2015; Martin & Everett, 2023), burial practices and beliefs (Jamieson, 1995; Davidson & Mainfort, 2011; Bigman, 2014), social hierarchies and inequalities (Davidson, 2004; Franklin et al., 2020; Lemke, 2020) and health and mortality (Davidson, 2007, 2008; O'Donnell & Edgar, 2021) within African–American communities.

Recently, archaeological efforts around historic African–American cemeteries have also become a rallying point for a discipline coming to terms with structural racism and aiming to establish an antiracist future for the field (Dunnavant et al., 2021; Flewellen et al., 2021; Franklin et al., 2020; Westmont & Clay, 2022). Westmont and Clay (2022) outline a path for archaeologists to address historical and present-day marginalization by ‘generating new stories and monuments where recognition is sorely lacking’ and ‘through careful and deliberate actions that empower communities’ (see also Lee & Scott, 2019). This path is consistent with Davis and Sanger's (2021) broader call for new attention to remote-sensing ethics, especially their recognition that archaeological research, no matter how methodologically focused it may be, can have broader social and political ramifications for the stakeholder communities.

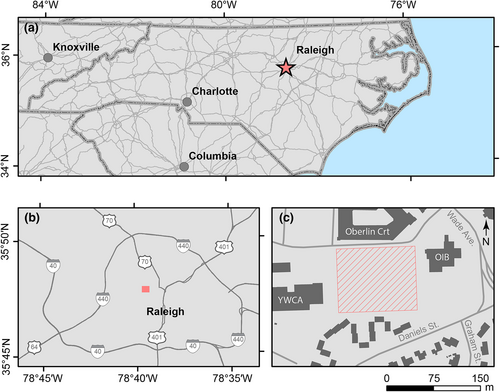

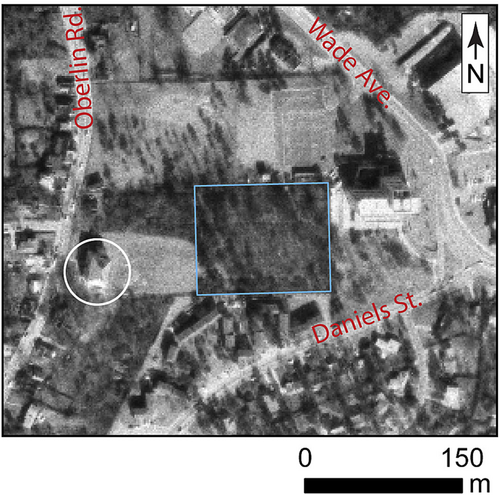

This study investigates Oberlin Cemetery (Figure 1), one of four known African–American cemeteries within Raleigh, North Carolina, USA (Little, 2012). This cemetery, founded in 1873, served the community of Oberlin Village—the largest freedmen's village in Wake County. Although the cemetery fell into disrepair during the late 1900s, a nonprofit group, the Friends of Oberlin Village (FOV), is actively working to maintain the grounds, which serve as a focal point for highlighting the neighborhood's history and preserving its remaining historic resources. Ongoing research and outreach collaborations between the FOV, community members and researchers at North Carolina State University, William Peace University,and Wake Tech Community College target the preservation of this African–American cemetery as a means of expanding the inclusion and diversification of black lives into archaeological and historical narratives (McGill et al., 2020, 2021; Melomo et al., 2020). This project began over 7 years ago when preliminary geophysical data were collected as part of an undergraduate class project, which provided a cost-effective way to help address the archaeological survey needs identified by the FOV. Although this collaboration was not designed initially along the co-production lines that Westmont and Clay (2022) have called for (for case studies in practice, see Scott, 2018; Flewellen et al., 2021; Jenkins, 2021), with the trust built through continued engagement, it has developed into that kind of collaboration.

Here, we present the initial research results conducted on behalf of the FOV, which included terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), global-positioning-system-enabled pedestrian and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys. These surveys were conducted to assess the cemetery's borders, document material culture and estimate the number of interred persons. Oberlin Cemetery presents several challenges to the archaeological survey: It has a dense canopy of mature trees, significant surface vegetation, an uneven surface, missing grave markers to suspected graves and numerous purposefully deposited but poorly visible surface artiefacts (e.g. glass bottle grave offerings, fallen and rusted metal wreath stands and flower vases). These challenges are, in many cases, characteristics of historic African–American cemeteries (Chicora Foundation, 1996; Rainville, 2014; Theberge, 2023), which are threatened by development associated with demographic and community changes over time (Dunnavant et al., 2021).

Pedestrian, or field-walking, surveys catalogue and describe material culture within a site. The spatial location of these features may be recorded using grids, traditional surveying techniques or global-positioning system technology (Gaffney, 2008; Newhard et al., 2013). For cemetery investigations, pedestrian surveys have traditionally focused on identifying and transcribing headstones to ascertain the names, ages and death dates of those interred and less commonly on documenting fieldstones and other historical artefacts (Amari & Alsulaimani, 2016; Rainville, 2009). The use of digital technology at a field site promotes dynamic, context-driven data entry that minimizes transcription errors and facilitates rapid documentation (de Vega & Agulla, 2008; Opitz & Limp, 2015).

Terrestrial laser scanners generate a three-dimensional model of the physical environment. These systems use time-of-flight or continuous frequency-modulated lasers to measure the distance to surfaces from multiple scan points. In cemetery investigations, TLS has been used principally to record the shape and locations of monuments (Weitman, 2012). However, point cloud data can also be gridded to produce high-resolution digital elevation models (DEMs) with cm-scale vertical accuracy. Such data can illuminate subtle landscape features, including sunken graves, walkways or other markers used to subdivide a cemetery (Aziz et al., 2016; Majewska, 2017). Although the technique cannot typically resolve monument inscriptions, it is often deployed alongside pedestrian survey efforts.

GPR is a geophysical remote-sensing technique that provides information on the stratigraphy of the shallow (typically < 2–3 m depth) subsurface. A GPR system transmits a pulse of electromagnetic energy that propagates downward into the subsurface and is reflected upward as the wave encounters geologic layers or buried materials with different electrical properties (Conyers, 2014). While the effectiveness of this approach in grave identification depends on local soil conditions and mortuary practices (Gaffney, 2008), this noninvasive technique has become a standard method in many cemetery investigations and can be critical in delineating burials not accounted for by archival records or formal grave markers (Aziz et al., 2016; Damiata et al., 2013; Doolittle & Bellantoni, 2010; Kadioglu et al., 2013).

In this study, data from field investigations and geophysical surveys were spatially enabled within a geographic information system (GIS) to create the first digital maps of the site. These observations were further integrated with georectified historical maps and land records. This archival information tracks the historical change of Oberlin Cemetery and the more modern redevelopment of properties within the historic Oberlin Village area. The findings reported here address two of the research goals we established with the FOV: (1) to document the history of the cemetery, including the historical and contemporary boundaries of the site and (2) to assess whether prior estimates of the number of interred individuals were accurate, which is a challenge given the large number of unmarked graves. Moreover, this study provides qualitative and quantitative data on African–American mortuary practices and first-order insight into the demographics of interred persons, which are interpreted within the broader field of African–American historical archaeology.

1.1 Historical and cartographic analysis

Why is there uncertainty about Oberlin Cemetery's boundaries and the number of individuals buried within it? The most likely reason is what historian Jill Lepore (2021) recently called the ‘apartheid of the departed.’ She uses this term to refer to how racialized violence targets the living and the dead, in this case, the lack of institutional support for Black cemeteries in the Jim Crow Era—and in some cases their destruction—in the name of urban renewal projects. In this light, it is worth reviewing the history of Oberlin Cemetery and its documentation to understand better the need for this project and others like it.

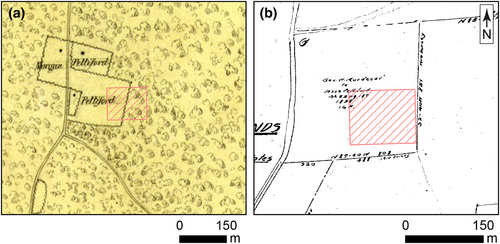

In 1858, a free African–American, Jesse Pettiford purchased 16 ac (6.47 ha) of land, encompassing portions of the future Village of Oberlin, from George W. Mordecai (Wake County, North Carolina (2016a), Deed Book 22: 187) . Land belonging to Pettiford was identified on an 1865 map of the Confederate lines in Raleigh (War Department, 1865; Figure 2a). The deed mentioned above is also depicted on a map of historical property lines from the mid-1800s produced in 1920 by C.L. Mann, a surveyor and Professor of Civil Engineering at North Carolina State University (Mann, 1920; Wake County, North Carolina 2018; Figure 2b).

Oberlin Cemetery was formally established in July of 1873. Wake County Deeds (40: 445) indicate that Nicholas Pettiford, the son of Jesse Pettiford, sold one acre (0.4 ha) of land to the village trustees of Oberlin Cemetery for 45 dollars (Wake County, North Carolina, 2016a). Although no plat survey of Oberlin Cemetery has been identified from this period, the land was described as located in the Village of Oberlin and bordered by properties owned by the late George W. Mordecai on the east, Albert Pettiford on the south and Luvinia Pettiford on the west.

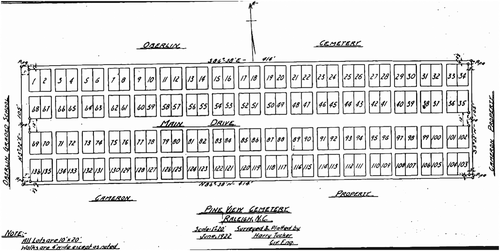

Professor Harry Tucker, a colleague of C.L. Mann, surveyed the land immediately south of Oberlin Cemetery in 1924 (Wake County, North Carolina (2016b), Map Book: 81; Figure 3). His map identifies land purchased by John T. Turner from Albert Pettiford in 1920 as the Pine View Cemetery (Wake County, North Carolina (2016a), Deed Book 368: 440). Although there is no record of these lands later being formerly recombined by deed, Pine View represents an annex to the main Oberlin Cemetery. Tucker's map shows plans for 136 family plots in four east–west trending rows covering an area of one acre (0.4 ha).

A US Geological Survey (USGS) 15′-topographic quadrangle from 1943 does not show Oberlin Cemetery (Reeves et al., 1943). It also fails to identify the Oberlin Graded School, which the community had built on the parcel of land immediately west of the cemetery in the early 20th century. However, the quadrangle map denotes Needham B. Broughton High School, a historically White school a short distance away, although it is incorrectly labelled Saint Mary's School.

In 1954, J.W. York and R. A. Bryan, local developers, commissioned a survey of their land between Daniels Street and Wade Avenue. The resulting maps show Oberlin Cemetery and identify an access road between the cemetery and Oberlin Road to the west (Wake County, North Carolina (2016b), Map Book 48). Just 2 years later, in 1956, The Occidental Insurance Company Building was constructed immediately to the east of the cemetery (Wake County, North Carolina, 2016c) (Figure 1). In 1958, a new Oberlin Road overpass was built to accommodate the expansion of Wade Avenue helped ease the flow of traffic into and out of downtown Raleigh (Little, 2012). Although the overpass did not directly impinge on the cemetery, like many urban renewal projects that fractured African–American communities throughout the country, the expansion of Wade Avenue cut Oberlin Village in half and resulted in the loss of homes in the community. The impacts of this fracturing would be evident in the cemetery over the next fifty years.

The 1968 USGS 7.5′-topographic quadrangle (1972 ed.) denotes the cemetery and Oberlin Graded School (U.S. Geological Survey, 1968). Aerial photography from the same timeframe (US Geological Survey, 1970; Figure 4) shows a contiguous wooded area (1 ac or 0.4 ha) encompassing the cemetery and land north of the Oberlin Graded School. By 1975, however, the Oberlin Graded School was demolished and replaced by a Young Woman's Christian Association (YWCA) facility next to the cemetery (Wake County, North Carolina, 2016c) (Figure 1).

In 2003 and 2005, lands immediately north of Oberlin Cemetery were recombined to construct the Oberlin Court Apartment complex (Wake County, North Carolina (2016b), Map Book: 855). Plat maps indicate that only the northern and eastern boundaries of the cemetery, which abut the Oberlin Court and Occidental properties, were surveyed at this time (Wake County, North Carolina (2016b), Map Book: 1744). During the construction of the Oberlin Court Apartments, parking lot and driveway surfaces were excavated, and fencing and stone retaining walls up to 2 m high were installed along these property lines. Because of commercial development within the formerly wooded area to the northwest, today, the 3.24 ac (1.31 ha) cemetery property can only be accessed from the west through the parking area of the former YWCA building (now owned by InterAct of Wake County) (Figure 1c).

This history of use, survey, mapping and surrounding development suggests several episodes in the history of the community and the cemetery that bear on our confidence in establishing the boundaries of the cemetery and the number of people buried within it. Land purchases and development in the 1920s, 1950s and 2000s may have reduced the size of the cemetery and disturbed or removed graves. Population changes, especially after the fracturing of Oberlin Village in the 1950s, may also have influenced burial practices in ways reflected in the size of the cemetery and its upkeep. We consider these periods in our analysis of findings below.

1.2 Previous surveys of Oberlin Cemetery

The first survey of the Oberlin Cemetery was conducted in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which reported death dates ranging from 1876 to 1913 (Little, 2012). Jennifer Hallman (unpublished) conducted an archival survey in the 1990s using the WPA survey results and the Wake County Death Registry. Hallman's study also involved interviews with community elders and some field observations; however, no attempt was made to fully inventory monuments within the cemetery. Nevertheless, her study provided evidence for the burial of 332 individuals between 1876 and 1992 at Oberlin Cemetery.

M. Ruth Little, a local historian, conducted a pedestrian survey of the cemetery in 2012. Her work was motivated by the formation of the FOV community group the previous year and supported their efforts to have Oberlin Cemetery placed on the City of Raleigh's historic landmark registry. Little's survey established a 10 × 10 ft (~3 × 3 m) grid system to reference the position of material culture within the cemetery. In addition, she produced a tabular database of 147 monuments (primarily burial and family markers) and transcribed the names, dates and dedications recorded on them.

2 FIELD METHODS

2.1 TLS survey

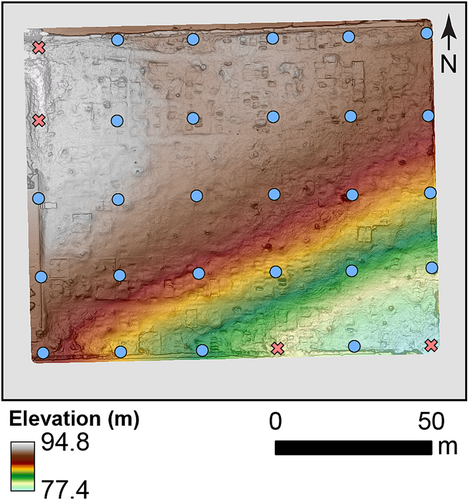

Oberlin Cemetery was surveyed in the winter of 2016 using a Leica HDS3000 TLS deployed at 26 locations throughout the cemetery (Figure 5). A minimum acquisition point spacing of 0.02 m was used. The scan data were combined into a single, unified point cloud using the Leica Cyclone 9.1.4 software. Tie points were established using the corners of 10 monuments, which were surveyed with a Trimble R10 global navigation satellite system (GNSS) receiver with real-time kinematic corrections supplied using a virtual reference station (VRS). As the onboard TLS camera was not functioning during the survey, only three of these tie points could be identified and used for georeferencing. The resulting RMSE of the survey was 0.80 m. Lidar ground points were classified using LAStools (http://rapidlasso.com/LAStools), with the ‘wilderness’ and ‘hyper-fine’ flags enabled. Ground-classified points were then thinned and gridded at a spatial resolution of 0.10 m. This grid size resulted in 14% of cells having ≤ 1 point per cell, while 86% have two or more points per cell. Most suboptimally constrained pixels were at the edges and within densely vegetated areas. Topographic expressions of plots outlining areas of family-related burials were digitized at a 1:250 scale.

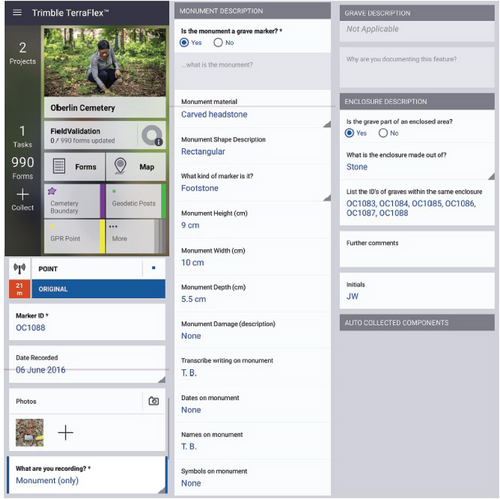

2.2 Pedestrian survey

Pedestrian survey data were recorded in the field during the summer of 2016 using a Trimble R10 GNSS-VRS receiver. Data collection utilized a custom-built digital form that provided adaptive menu choices and data entry fields. The form was developed using the Trimble TerraFlex application programming interface (Figure 6), which communicated with the R10 receiver using a Bluetooth connection. Positional information was recorded at the southwestern corner of each feature. Horizontal accuracy ranged between 0.01 and 2.93 m, with a mean of 0.15 m and a standard deviation of 0.24 m.

Items of material culture were organized by categories: (1) Carved Stones, including worked and engraved headstones, footstones, and obelisks; (2) Cement Markers that were cast or poured and used as headstones and footstones; (3) Fieldstones, consisting of local schist and large quartz crystals which were predominate markers from the Colonial period through the 1870s (Chicoria Foundation, 1996; Rainville, 2008; Stone, 2009); (4) Metal Plaques made by casting or pressing metal as well as pressed metal frames; (5) Wooden Headboards; and (6) Other which included items such as conch shells, vertical-oriented terracotta pipes, and pieces of metal scrap. Each feature was photographed, and its dimensions were recorded (Figure 7). In addition, the names, dates and dedications were transcribed for carved stones, cement markers and metal plaques. These data guide our estimate of the number of graves and spatial boundaries of the cemetery.

The cemetery landscape is marked by numerous elongate topographic depressions, with morphologies consistent with subsidence associated with graves (Aziz et al., 2016). The dimensions of each depression, as visible within the field, were recorded using a tape measure. To facilitate later comparisons with the TLS data, leaf litter and vegetation were not removed before making these measurements.

Tables were generated containing attributes that could be queried to summarize the data by record class (monument, monument and sunken grave and sunken grave), material, inscriptions and preservation state. Field notes, transcribed names, photographs, topographic data and geospatial relationships were used to associate primary (e.g. headstone) and secondary (e.g. footstone) monuments with unique burials. For example, nameless metal plaques, wooden headboards and heavily weathered carved stone were associated with burials based on their continuity of form with other monuments within the cemetery.

2.3 GPR survey

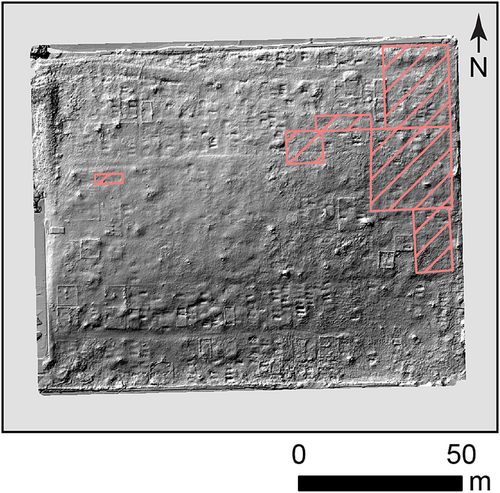

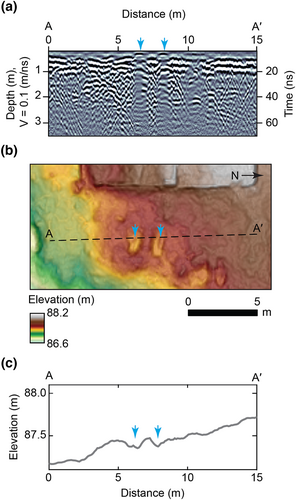

A GPR survey was carried out over ~12% of the cemetery (Figure 8) to validate our interpretation of closed topographic depressions as sunken graves and assess its potential for locating unmarked graves. A more extensive GPR survey was judged impractical due to the undulating terrain and prevalence of trees and shrubs across large portions of the site. Both 250 and 500 MHz Sensors and Software Pulse EKKO Pro radar antennae were deployed on a cart chassis. Survey lines were collected in a roughly north–south (grave-normal) direction with 0.5 m spacing between lines. Trace data were stacked 16 times and triggered at 0.05 (250 MHz) and 0.02 m (500 MHz) intervals along each line. An average radar velocity of 0.1 m ns−1 was estimated by fitting hyperbola throughout the survey area. The maximum radar penetration depth was ~2.5–3.0 m.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Material culture, grave markers and burials

The pedestrian survey generated 1087 records (Table 1) within the cemetery. This includes 276 grave markers (headstones and footstones) constructed from carved stone (n = 160), poured cement (n = 67), metal plaques (n = 47) and wooden headboards (n = 2). Nearly half (n = 126) of these markers exhibited physical or chemical weathering on their surfaces. A further 234 records list ‘other’ objects of material culture. Of the combined 510 grave markers and other items, 221 were interpreted as the sole or primary burial marker of one or more persons (Table 2). Classification as a primary burial marker was determined by the inscription of names (n = 132) or other identifiers (n = 4), the association of an uninscribed monument with a sunken grave (n = 29) or based on the continuity of a monument's form (e.g. a metal plaque, wooden headboard, heavily weathered carved stone lacking discernable markings) (n = 56). Other items of material culture identifying unique burials are itemized in supporting information Data S1.

| Material | Monument (disrepair) | Monument and grave (disrepair) | Sunken grave | Total (disrepair) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carved Stone | 144 (58) | 16 (7) | - | 160 (65) |

| Cement marker | 59 (23) | 8 (7) | - | 67 (30) |

| Metal plaque | 32 (21) | 15 (8) | - | 47 (29) |

| Wooden headboard | 2 (2) | 0 | - | 2 (2) |

| Fieldstone | 259 | 13 | - | 272 |

| Other | 234 (4) | 9 | - | 243 (4) |

| Nothing | - | - | 296 | 296 |

| Sum | 730 (108) | 61 (22) | 296 | 1087 (130) |

| Material | Monument | Monument and sunken grave | Sunken grave | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inscribed with name | Inscribed without name | Uninscribed | Inscribed with name | Inscribed without name | Uninscribed | |||

| Carved stone | 75 | 1 | 20 | 14 | - | 2 | - | 112 |

| Cement marker | 23 | 3 | 9 | 3 | - | 5 | - | 43 |

| Metal plaque | 13 | - | 16 | 2 | - | 13 | - | 44 |

| Wooden headboard | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| Fieldstone | - | - | 130 | - | - | 13 | - | 143 |

| Other | 2 | - | 9 | - | - | 9 | - | 20 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 296 | 296 |

| Sum | 113 | 4 | 186 | 19 | 0 | 42 | 296 | 660 |

A total of 158 individuals (supporting information Data S2) are identified from 137 records. A total of 128 birth dates and 142 death dates were transcribed. In a handful of cases, the inscriptions on monuments could not be read with confidence due to weathering, or it could not be determined if a date referenced the birth or death of an individual. One individual, Mattie E. Williams was identified by two monuments with different birth dates. In addition, some monuments identify more than one person.

Fieldstones are unworked or minimally worked rocks lacking inscriptions that may serve as burial markers (Helsley, 1997). A total of 272 fieldstones were surveyed at Oberlin Cemetery. Of these, 13 were spatially associated with sunken depressions, consistent with being interpreted as burial markers. An additional 130 might be considered unique grave markers based on their location within rows and upright positioning (143 total). Some remaining fieldstones appear to delineate family plots, while others are arranged in a less-organized manner, making their function within the cemetery less clear. Prior research has indicated that fieldstones were common burial markers throughout the southeastern United States during the 17th to 19th centuries (Brandon & Hilliard, 1998; Helsley, 1997; Rainville, 2008; Stone, 2009). There are, however, a total of 36 fieldstones in the 1920 Pine View annex, suggesting that their use continued into the 20th century or that burials occupied this area before its official annexation.

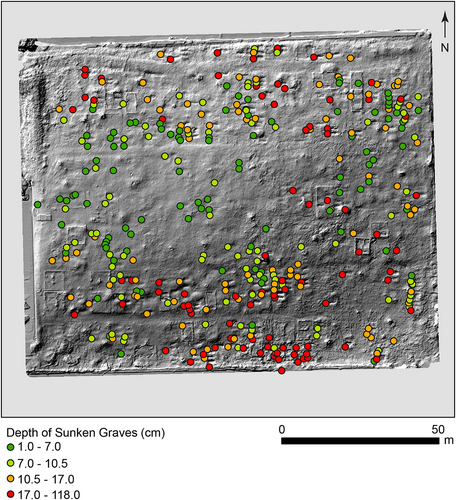

Based on their size and morphology, 357 topographic depressions were identified in the field as possible sunken graves (Figure 9). The length, depth and widths of each sunken depression are summarized in Table 3. Of these records, 61 were associated with monuments including carved stones (n = 16), cement markers (n = 8), metal plaques (n = 15), fieldstones (n = 13) and other items of material culture (n = 9). The remaining 296 depressions were not associated with grave markers. A comparison of these field observations with TLS data showed that ~89% (n = 318) could be identified visually in the hill-shaded elevation dataset (e.g. Figure 9).

| Metric | Sample size (n) | Minimum (cm) | 25th percentile (cm) | 50th percentile (cm) | 75th percentile (cm) | Maximum (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth | 355 | 1 | 7 | 10.5 | 17 | 118 |

| Width | 356 | 44 | 78 | 88 | 103 | 212 |

| Length | 357 | 110 | 204 | 222 | 236 | 288 |

- Note: Depth and width measurements were not always determinable in the field. Depth was indeterminate for two records, OC0192 and OC0760, due to dense vegetation and subtle topographic expression. Width was also indeterminate for OC0192 because of vegetation.

Based on the pedestrian survey results, Oberlin Cemetery contains 221 primary burial markers, which list the names or initials of 158 individuals (supporting information Data S2). In addition, 296 sunken gravesites cannot be associated with a formal grave marking monument or fieldstone. Combining the primary burial markers with the sunken graves associated with a marking monument or fieldstone results in a conservative estimate of 517 interred individuals. An additional 143 fieldstones were also identified, positioned in a manner consistent with use as a burial marker. We, therefore, estimate a maximum of 660 individuals buried within Oberlin Cemetery.

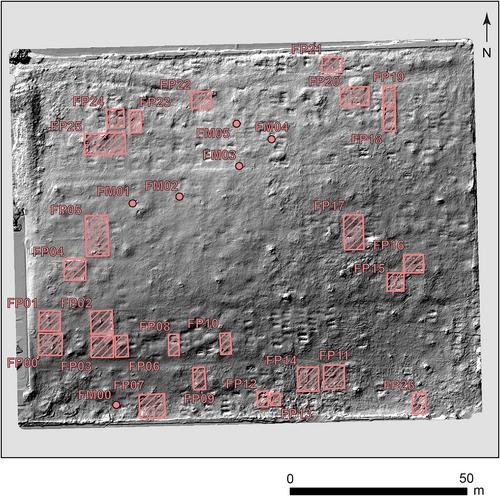

3.2 Pathways and enclosures

The TLS data reveal the presence of a curved pathway near, but not coincident with, the currently recognized northern boundary of the cemetery (Figures 5 and 9). The road, which is ~4 m wide, enters the cemetery near its northwest corner, meanders slightly to the south and then exits near the northeast corner of the property. This feature divides a narrow area of graves, including one family plot, from the main cemetery to the south (Figure 10).

The TLS data also highlight 27 enclosures inventoried as part of the pedestrian survey. Supporting information Data S3 documents the diversity of construction approaches and material culture within these enclosures. The Dunston family plot, located just inside the cemetery entrance, is outlined by worked stone pillars connected with a linked chain and contains a tall (~2.5 m) obelisk monument. Similarly, the Turner family plot, located at the entrance of Pine View Annex, is surrounded by a short iron fence with stone corners and contains a marble bench and large grave monuments. The ornamental characteristics of these two enclosures may denote the socio-economic standing of the families within the community. Not all family enclosures, however, are as ornate. Some additional family plots (n = 6) are marked by a family monument and lack a walled or fenced enclosure. In addition, enclosures do not always contain a single-family name. In three cases, more than one family name is listed on grave markers within an enclosure that contains a family monument. Five other enclosures list multiple family names on grave markers but do not contain identifiable family monuments (supporting information Data S3).

3.3 Demography

The grave markers record the intimate lives of Oberlin Village's population over the last 150 years. Men and women, young and old, from all walks of life, are buried at Oberlin Cemetery (supporting information Data S2). While we recognize that all individuals buried in the cemetery had life experiences that may not be evident on their grave markers, many grave markers denote the identities and social positions of the deceased. Religious symbols are exclusively Christian and include engraved crosses. Lamb of God sculptures top two tombstones associated with children. Carvings of ivy leaves and anchors are also common throughout the cemetery. Five military veterans are buried within the cemetery—one from the Spanish-American War and four from World War I.

Six monuments display the Masonic Square and Compass of the Freemasons, five monuments with three interlocking chains denoting membership in the Ancient Order of Oddfellows and one inscription referencing the Eastern Star Lodge. Therefore, evidence of membership in fraternal or sororal societies can be found on 7.5% of the carved stones. Symbols representing these organizations are common within African–American cemeteries of similar age (Davidson, 2004; Schwenk, 2001). These societies played an important role in helping to cover the burial expenses of their members and often provided a level of economic security for families (Skocpol & Oser, 2004).

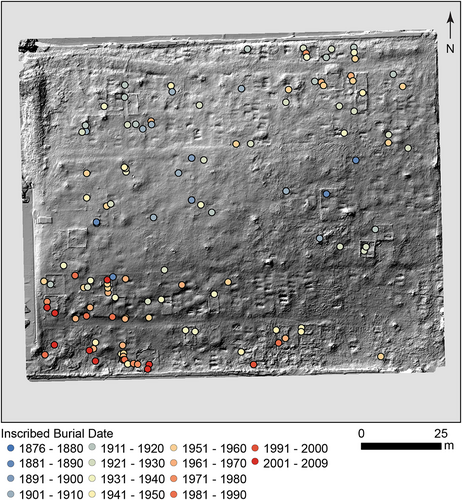

The distribution of birthdates within Oberlin Cemetery is left-skewed (Figure 11a). It shows that ~23% of those individuals having inscribed (readable in 2016) monuments were born before the end of the American Civil War (ca. 1865), with the earliest born in 1804. The youngest individual identified on a grave marker was 1 day old, while the oldest lived for 102 years. The earliest grave with a legible inscription on a monument dates to 1876, consistent with the WPA and Hallman survey results. The median year of burial was 1937, and the cemetery was used regularly through the early 1970s (Figure 11b). The burials decreased during the 1980s and 1990s as the cemetery grounds fell into disrepair. Eight individuals, however, have been buried in Oberlin Cemetery since 2000. The ongoing history written on the gravestones at Oberlin Cemetery remains an anchor for the community and an important source of knowledge for future generations.

The clustering of fieldstone markers along the central-western edge of the cemetery might be interpreted to indicate that this is the oldest part of the cemetery. However, our pedestrian survey shows that markers with older dates are distributed throughout the cemetery. Death dates on inscribed monuments similarly show no spatial pattern beyond the more recent (after 1970) burials concentrated in the cemetery's southwestern corner (Figure 12). This lack of patterning by date is consistent with burials being organized primarily around familial associations. Graves for Oliffe Poole and Lula Turner, located along the northern edge of Pine View Annex, have death dates before its 1920 creation.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Cemetery boundaries

Several lines of evidence suggest that the boundaries of Oberlin Cemetery recognized today may not reflect its historical limits. First, the presence of fieldstone markers in the Pine View annex at the south of Oberlin Cemetery is anomalous given that their use is believed to have ended in the 19th century and the annex was only added in 1920. If the fieldstones in the Pine View annex represent pre-1920 burials, then that would mean that earlier cemetery plans did not accurately represent its full spatial extent.

The present-day northern boundary of the cemetery is defined by a retaining wall stepping down to the paved parking area around Oberlin Court Apartments, which were built starting in 2003. Falling between the old access road and the new Oberlin Court Apartments parking area is a small wedge-shaped area of graves, with the northernmost burials (markers and sunken graves) positioned within metres of the retaining wall (Figures 9 and 12). The most recent dated grave marker in this area is from the 1970s, which suggests that by the time Oberlin Court Apartments began construction, few families were accessing this portion of the cemetery, and therefore, potentially fewer people had intimate knowledge of the northern boundary or a vested interest in maintaining it.

In contrast, there appears to be a much greater continuity of space and burial practice along the western boundary of the cemetery. For example, family plots within this area show burial activity ranging from the 1920s to the 2000s (Figure 10), and nearly all post-1970 burials are positioned in the southwest corner of the cemetery (Figure 12). This continued use would have promoted greater advocacy and stewardship of the area.

A steep incline marks the cemetery's eastern boundary down to the paved parking area of the Occidental Insurance Company Building, constructed in 1956 (Figures 1 and 4). As with the northern margin of the cemetery, burials extend within meters of the present-day property line. However, as there are no family plots or dated markers in this area, the continuity of the cemetery's eastern boundary is more difficult to assess.

4.2 Database comparison

The prior field survey work in 2012 for the City of Raleigh Landmark (CRL) study generated 147 records (Little, 2012). Approximately 86% (n = 127) of these records could be positively identified within the database generated by the 2016 pedestrian survey, including grave markers with (n = 114) and without (n = 2) names, as well as family monuments (n = 11). During the pedestrian survey, location information was recorded utilizing a high-resolution GNSS-VRS receiver; however, the CRL survey recorded only the grid (10 × 10 ft) in which each record existed. Given the written descriptions and ambiguity in the location provided by the CRL survey, 15 records could not be positively correlated with the pedestrian survey database. However, an additional five CRL survey records (headstones) are absent within the pedestrian survey database. Subsequent efforts, which enlisted local community members, have failed to locate these headstones, suggesting that they have been damaged or displaced during the interval between the two surveys. This discrepancy represents an ~3% loss over 4 years. Moreover, this implies that some burials may have no material or geomorphic expression in the present-day cemetery and, therefore, would be absent from our field-based inventory.

The CRL survey created a registry of 138 people buried in Oberlin Cemetery, whereas this pedestrian survey identified 158 individuals—representing a 15% registry increase. Both surveys record the earliest burial being that of Julia Andrews in 1876. Although the CRL survey reports the use of the cemetery through only 1971, our pedestrian survey identifies 19 later burials, the most recent being in 2009. In total, the pedestrian survey identified 25 individuals and three family monuments absent from the CRL survey database.

4.3 Unmarked grave identification

Where burials are suspected to be present, but no grave markers exist, GPR has been used by other studies to confirm their presence (Aziz et al., 2016; Damiata et al., 2013; Doolittle & Bellantoni, 2010; Kadioglu et al., 2013). Despite the presence of clay-rich (conductive) soils within Oberlin Cemetery, the radar's 2.5–3.0 m depth-of-penetration was sufficient for imaging the burials at this site (Figure 13a). However, the vegetation cover on site made a detailed scan ( 0.5 m line spacing) of the entire area impractical. Moreover, our partial (~12%) GPR survey of the cemetery revealed a tendency for the radar system to decouple while crossing many of the sunken graves. This situation results from a seperation of the antennas from the ground surface as they pass over topographic depressions. In addition, a thick accumulation of leaf litter within some topographic depressions reduced GPR coupling. While indications of burial can often be gleaned from these radargram images, this change in radar coupling makes interpretation more complex and generally renders depth slicing ineffective (e.g. Conyers, 2014).

As an alternative approach, this study has relied on the prevalence of sunken graves to constrain the minimum number of unmarked burials within Oberlin Cemetery. The topographic expression of these sunken graves was identified during the pedestrian survey, and these features are visualized using the TLS-derived elevation model (Figure 13b,c). Identifying these features within topographic data is consistent with observations by Weitman (2012) and Aziz et al. (2016). Given the consistency of these observations and the impracticality of cemetery-wide GPR surveys, unmarked burials may be best inventoried in some settings using their topographic signal.

4.4 Formation of sunken graves

The Oberlin Cemetery site consists of clay-rich (Cecil series) soils developed over late Proterozoic to Paleozoic felsic gneisses (Blake, 2008). The formation of sunken graves is driven primarily by sediment compaction, with much of the settling occurring in the initial months to years after a burial (Scott, 1980) and the collapse of caskets within the subsurface over longer timeframes. Therefore, the occurrence of a sunken grave depends on the site's leveling and maintenance over time, as well as the construction materials, with caskets likely transitioning from wooden to sheet metal construction in the mid-20th century (Northwoods Casket Company, 2011; Casket & Funeral Supply Association of America, 2023).

Of the 87 grave markers that record death dates of 1950 or earlier, only 6% are associated with a sunken grave. In contrast, of the 55 grave markers that record death dates more recent than 1950, 20% are associated with a sunken grave. These observed differences are statistically unlikely (p ≈ 0.05) when tested using a binomial probability model; however, as <5% of the sunken grave burials can be dated and some grave markers are likely lost over time, this pattern should be interpreted cautiously.

The deepest depressions are found within the Pine View portion of the cemetery (Figure 9), not annexed until 1920. While this pattern could reflect a shift in mortuary or maintenance practices over time, local hydrologic and soil conditions also may influence the amount of settling and the prevalence of casket collapse. Surface runoff drains to the southeast (Figure 5), and water has been observed to pool on the surface in this part of the cemetery after heavy rainfall events.

5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Pedestrian survey and TLS datasets collected in 2016 provide baseline information for preserving and managing Oberlin Cemetery in Raleigh, North Carolina, USA. This cemetery, founded in 1873, served the historic African–American community of Oberlin Village—the largest Freedmen's community in Wake County (Little, 2012). Today, with continued development within the neighborhood, the cemetery serves as a focal point for community efforts to preserve the area's history. In addition, investigations at Oberlin Cemetery are relevant beyond the local community. They can serve as a basis for exploring the diversity of African–American experiences, especially those of Freedmen's (Scott, 2018) and other African Diaspora communities (Odewale, 2019). The findings support the Oberlin Village community's initiatives to maintain and highlight Oberlin Cemetery.

The pedestrian survey documented 276 burial markers constructed from carved stone, cement, wood and metal. Of these, 221 are interpreted to be the sole or primary identifier for the burial of one or more individuals. In addition to these formal grave markers, the survey recorded 272 unworked or minimally worked fieldstones, which were common grave markers in use throughout the southeastern USA through the 19th century (Rainville, 2008; Stone, 2009). Based on their alignment, positioning or association with a sunken grave, as many as 143 of these fieldstones could represent grave markers. The pedestrian survey also catalogued 357 elongate topographic depressions that we interpret as sunken graves that likely formed due to soil subsidence above the casket, subsurface casket collapse or both processes. Of these small depressions, 296 occur at sites not otherwise marked by formal burial markers. Summing unique observations, the number of persons interred within the cemetery, is estimated to be between 517 (formal burial markers and sunken graves) and 660 (formal burial markers, sunken graves and fieldstones). The lower bound of this estimate is greater than a 1990s archival-based inventory (n = 332; J. Hallman, unpublished), suggesting that field surveys can complement or expand the estimate of individuals within a cemetery. Based on our observations, the burial density average across the 3.2-acre community cemetery is one individual per every 20–25 m2 (165–205 burials per acre). This is much less than the estimated one burial per 3.23 m2 (1150 burials per acre) reported for Freedman's Cemetery in Dallas (Condon et al., 1998) or modern municipal cemeteries, which are typically subdivided into 800–1200 plots per acre.

Comparing the results of a 2012 grid-based inventory (cf. Little, 2012), the 2016 pedestrian survey identified 25 individuals not listed as part of the CRL application—expanding the cemetery registry by 15%. The survey, however, failed to identify five headstones (~3%) located in 2012. These omissions suggest that monuments may have been displaced or severely damaged over the 4 years and highlight the need to document material culture within historic cemeteries and the importance of sustained preservation efforts.

The FOV used results from this work to support Oberlin Cemetery's successful nomination to the US National Register of Historic Places, thereby protecting this focal point of African–American heritage. Additionally, as stewards of the cemetery, the FOV has successfully applied for and received site preservation funds, ensuring the cemetery's historical significance will be maintained for generations to come. Continued collaboration with the FOV and other members of the local and descendant community will provide new opportunities to co-produce research of use to the many people of these communities. Such work is done to advance the ethical practice of archaeology in a manner that helps showcase the social heterogeneity and complexity of the community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Friends of Oberlin Village and InterAct for facilitating access to the cemetery. Andy Jordan, Heather Paxson, Lisa Picariello, Kevin Walker, Jeffery Weis, Morgan Whited and Natalia Womack assisted in the field survey. Their efforts were supported by U.S. National Science Foundation Award #1107916 through a partnership between Wake Technical Community College and N.C. State University to increase diversity in the geosciences via applied student research experiences. The Santee Cooper Geographic Information Systems Laboratory provided the Leica HDS 3000 laser scanner, while Justin Barton assisted with the lidar scanning, access to Leica Cyclone software and georeferencing. In addition, Meg Watters and Jim Newhard are appreciated for their GPR survey insight and information regarding landscape archaeology theory and methods, respectively. We thank the reviewers for their detailed comments and constructive suggestions, which significantly improved this manuscript.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supporting information of this article.