On Cemetery Hill: The legacy of burials at Clemson University, a public university in the southern USA

Funding information: Funding for this GPR investigation of Woodland Cemetery was provided through a contract to Preservation South, LLC from Clemson University.

Abstract

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) was used to map anomalies characteristic of unmarked graves on the grounds of the modern Woodland Cemetery on the campus of Clemson University. Hundreds of these anomalies are believed to represent newly discovered unmarked graves belonging to African Americans including enslaved people, convicted laborers, sharecroppers, domestic workers, tenant farmers and wage workers, who contributed to the wealth of the Fort Hill Plantation or to building and maintaining the university. These burials appear to be in an organized arrangement indicating the presence of a burial ground where the graves would have been marked at the time of internment. Analyses of reflections from the bottom of the grave shaft detected horizontal bases as well as possible chambered and vaulted burials, a common vernacular burial type among African Americans in the 19th and early 20th centuries. A fewer number of graves showed hyperbolic reflections that can be produced by graves that contain coffins or a large artefact. This may indicate burial practices that changed over time or the status of the interred individual. The estimated length of the grave shaft in GPR grid data suggests that small adults or adolescents made up most of the burials (58%), then adults (28%) and infants and children (13%). In 1924, Woodland Cemetery was developed on Cemetery Hill, which had its first recorded burial in 1837. Plots were then gifted to prominent University leaders, faculty, staff and their families. The unmarked burials were found juxtaposed among these modern graves requiring modification of the current protocol for the operating cemetery to preserve the sacred space and to prevent destruction of these burials. This work affirms ongoing efforts by this public university to address its origins from a plantation and segregation in the American South.

1 INTRODUCTION

Public universities in the southern United States own or are affiliated with legacy cemeteries with long, complicated histories dating to before the Civil War. Examples include cemeteries dating from 1810 at the University of Georgia, 1828 at the University of Virginia, 1835 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) and 1837 at Clemson University. These public institutions of higher learning are well known and attract students from across the country and around the world. The affiliated cemeteries include well-maintained graves and distinctive architecture, some meriting inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places (i.e., the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery at UNC-CH and Jackson Street at the University of Georgia), but they also include sections where burials are unmarked, and the burial grounds have been desecrated or completely disinterred during development. Pressure to develop new burial plots and to expand university cemeteries originates from Americans who identify more closely with their alma mater than with their hometown or organized religion. The desire for group identity in perpetuity has fostered interest in securing burial within university-owned or affiliated cemeteries or columbarium (Cronin, 2016). In 2012, the University of Virginia undertook a cemetery expansion into adjacent vacant land to provide plots for alumni and uncovered 67 previously unknown grave shafts beneath the stripped topsoil (Wolf, 2013). These graves were determined to be those of enslaved African Americans who were buried just outside the north wall of the established cemetery. The graves were left undisturbed as a memorial to enslaved people who built and maintained the university and the cemetery was expanded to the south (Wolf, 2013).

At UNC-CH, the Black Student movement drew attention to the need for repairs to the headstones remaining within the African American section of the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery that had experienced removal of grave markers, or vandalism as it had been used as overflow parking for home football games (Modzelewski, 1999). In response, Preservation Chapel Hill, the historical society contracted with Environmental Services, Inc. and Seramur and Associates, PC to identify unmarked burials using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and soil probing within African American sections of the cemetery. A total of 261 potential unmarked burials were located some of which were associated with uncarved field stones or depressions visible on the surface (Russ & Seramur, 2012). Most graves were determined to be those of enslaved people or university laborers, and others were faculty members or African American residents of Chapel Hill (Town of Chapel Hill, 2022). These graves are now mapped, and the burial grounds are maintained by the town of Chapel Hill, NC.

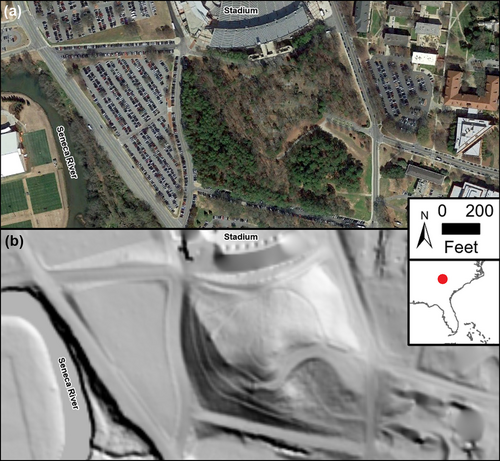

Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina was founded in 1889 as a public land-grant institution on Fort Hill, a plantation previously owned by John C. Calhoun (Thomas, 2018). In 1964, the name was changed to Clemson University with the goal of becoming one of the top public universities in the country. The University's mission statement emphasizes commitment to tolerance and respect for others, as well as development of ethical judgment and global awareness in its students (Clemson University Board of Trustees, 2012). This vision is complicated by the university's memorials to slavery on the Fort Hill Plantation and the Confederacy, for which ties persist to this day on campus (Thomas, 2018, 2020). A symbol of this history lies in the burials on Cemetery Hill, which occupies a central elevated landmark on the main campus (Figure 1a,b). The graves of the Calhoun family, beginning in 1837, are present on the summit. Domestic and agricultural enslaved people who worked on the Calhoun plantation were buried on the western slope of the hillside, but only one burial record has been identified from the Antebellum period; the death of Tom, an enslaved man who died in 1850, is described in the records of St. Paul's Episcopal Church. In 1922, Clemson trustees proposed Woodland Cemetery as the name for Cemetery Hill, and burial plots were assigned to past presidents, trustees, faculty, staff and their families. In January 1924, Walter Riggs, Clemson's President, became the first recorded interment prior to the establishment of Woodland Cemetery later that summer. In addition, many enslaved people and approximately a dozen convicted laborers who built the campus buildings were buried there over the years. Some of their graves were moved by court order from the western slope in 1960 to a designated area on the southern slope (State of South Carolina, Oconee County, 1960). In 2016, a historic marker was erected there to memorialize the ‘Fort Hill Slave and Convict Cemetery’. The footprint of the modern cemetery is approximately 17 acres and consists of three phases of marked burials, the Calhoun Family burials of the 19th century, the 20th-century burials on the east side of the cemetery and the later 20th century to present-day burials on the northern and western slopes.

In 2020–2021, Clemson University contracted with independent consultant, Preservation South, LLC who partnered with Seramur & Associates, PC to conduct a GPR Survey of Woodland Cemetery to identify and locate potential unmarked graves within the African American burial ground. The initial survey was requested after two Clemson students, Sarah Adams and Morgan Molosso, learned of the neglected burial ground during a cemetery tour and requested that the University clean up the site and install a memorial. Although the initial motivation for the survey was to confirm the existence and extent of the burials within the ‘Fort Hill Slave and Convict Cemetery’, background research conducted as part of the project indicated the potential for additional unmarked burials on the western slope. Here, we describe how a state-of-the-art geophysical survey was implemented on the grounds of Woodland Cemetery to elucidate the presence of unmarked graves. The ensuing discovery provides tangible proof for the Clemson University community that a large number of African American enslaved people, convicted laborers and postbellum burials of descendants of slaves and wage workers and their families were buried on Cemetery Hill. This knowledge has inspired additional research that seeks to recognize and memorialize a group of people who ensured the success of Clemson University (Thomas, 2020). In addition, changes in the management of Woodland Cemetery will establish the site as a sacred burial ground for all.

2 HISTORICAL CHANGES TO CEMETERY HILL AND GRAVE MARKERS

The area available to survey encompassed 34% of the original landform because the hill's topography was altered by construction to the north and west. In 1941–1942, the football stadium was constructed in a ravine to the north and the hillslope was later excavated in the 1970s for expansion of the stadium (Figure 2a). The hill once stretched to the Seneca River to the west (Figure 2b). In 1960, the lower half of the hill was removed to provide between 100,000 and 300,000 cubic yds of fill dirt for flood-control dikes constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers resulting in a steep terraced western slope (Figure 1b). During this excavation, burial remains believed to belong to African American children were uncovered and reburied on the southern slope (Cowan-Ricks, 1992). In 1946, Clemson's Building and Grounds Committee reported that between 200 and 250 graves of enslaved people and convicted laborers were buried on the west slope of Cemetery Hill (Minutes of the Building and Grounds Committee, 1946). This raises the question of why so many graves are unmarked, and if they were marked at one time allowing people in the past to know they were there. Although certainly some of the graves may have been marked with impermanent items like wood planks or cedar tree saplings (Fennell, 2011), the majority would likely have had at least one field stone at the head (Figure 3a). A review of the applicable records and aerial photography indicates that the site was used for parking for football games at the adjacent stadium in the middle of the twentieth century. This practice has not been allowed in decades, but it would not have taken long for burials near the loop road to have the markers knocked over or pushed into the soil by the weight of vehicles (Aerial photograph, 1974). Inspection of the cemetery for this study recorded a number of 20th-century stone wall grave enclosures constructed with small stones or fieldstones, held together with Portland cement (Figure 3b). These walls are covered by lichens and moss that obscures the stone surfaces. It is possible that these walls are created from fieldstones collected on the site by individuals, who may or may not have known what they were. A cursory examination of the walls does not reveal any carvings, but no inscriptions were observed on the surface of relocated markers in the fenced area either.

3 PREVIOUS STUDIES

Previous attempts were made to investigate the occurrence of unmarked burials in Woodland Cemetery. In the early 1990s, the University hired its first archaeology professor, one of the few black female archaeologists in the United States, Carrel Cowan-Ricks. Cowan-Ricks was a doctoral candidate, and her research focused on Pre-Civil War African American Cemeteries in the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia. Cowan-Ricks undertook archival research to establish the existence of the Antebellum cemetery and conducted archaeological excavations with students on the western slope in the summers of 1991 and 1992. The team excavated eight 3 × 10 ft, north–south oriented test plots, ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 ft deep (Cowan-Ricks, 1991). Her goal was to expose the upper portion of the grave shaft but not the actual burial. Cowan-Ricks kept detailed notes of the field excavations including descriptions of the soil horizons (Cowan-Ricks, 1991). However, her work did not result in the identification of any unmarked burials. In the fall of 1993, Cowan-Ricks' position at Clemson University was eliminated because of budget cuts.

In February 2005, Dr. Jonathan Leader, South Carolina State Archaeologist, conducted a GPR survey of two areas with at least 18 transects. He stated that no graves were found but no formal report was provided to the University.

4 GPR SURVEY METHODS

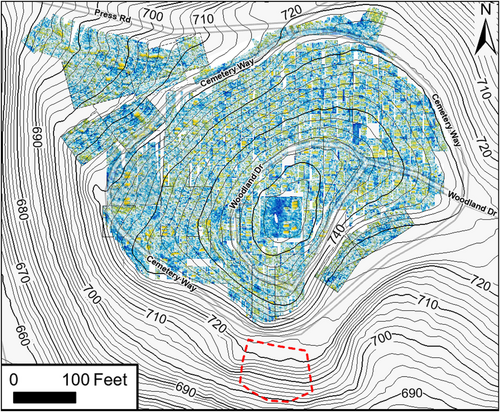

Our GPR survey was conducted over three phases of field work, beginning in July 2020 with collection of random GPR profiles on the southern and western slopes. Based on the results of that survey, Clemson University expanded the scope to include collecting transect data throughout the cemetery and marking anomalies within the GPR data indicating potential unmarked burials in the field with a white PVC pin flag. This phase of the work identified 667 anomalies, and the flags were surveyed and mapped by Summit Engineering. Following the results of the expanded GPR survey, Clemson University commissioned the collection of GPR grid data across the modern cemetery. Each grid consisted of parallel transects collected unidirectionally at 1-ft spacing in a north–south direction in order to cross each burial several times. Data were collected from 27 large grids in the more open areas of the hill. Smaller grids were collected across 220 individual family plots, and 36 grids were collected across roadways and aisles between the plots. In all, grid data were collected over about 5 acres of relatively level ground and GPR transects were run across another 4 acres of sloping terrain.

GPR data were collected using a GSSI UtilityScan GPR System with a 350-MHz hyperstacking antenna and a GSSI SIR 3000 with a 400 MHz antenna. These systems were able to image depths to about 8 ft within the Pacolet fine sandy loam (USDA, NRCS, 2022).

Data were transferred to GPR-SLICE for imaging profiles and three-dimensional (3D) volume interpolation. A time-zero correction was performed to designate the starting point of the received signal. An automatic gain control was applied to enhance reflections at depth, and a background filter was applied to remove horizontal banding. Hyperbola-fitting determined that velocities in this moist silt loam soil ranged from 0.17 to 0.07 m/ns. A velocity of 0.08 m/ns was used to estimate depths on the GPR profiles and amplitude slice maps. The 3D volumes were obtained in GPR-SLICE by sampling all profiles over the same increments of a two-way travel time, 2.4 ns or 0.3 ft.

4.1 Identifying graves in GPR data

Identification of historic unmarked graves with GPR requires understanding the radar response to the physical properties of the target, which have been described in many case studies (Berezowski et al., 2021; Bigman, 2014; Dick et al., 2017; Downs et al., 2020; Goodman & Piro, 2013). Unmarked graves prior to the later 20th century likely consist of an excavation with a shroud burial or a wooden casket (Perry et al., 2006). As the human remains decay, the backfill in the grave shaft expands to fill this void. The acidic upland soils on Cemetery Hill (USDA, NRCS, 2022) are expected to destroy the remains so after 100 years; only loose homogeneous backfill occurs within the grave shaft. Therefore, unmarked burials are identified by the contrast in soil density and moisture content between the undisturbed saprolite and the homogeneous backfill in the grave shaft. A potential grave shaft is identified where shallow reflections off the edges of the grave shaft are paired with a horizontal reflection at depth. To be certain that it is not isolated soil disturbance, adjacent GPR profiles were observed to identify similar reflections. It is important to identify patterns rather than an isolated area of soil disturbance (Conyers, 2006, 2012). Similarly, on GPR depth slices, unmarked burials produce a distinctive anomaly. In areas of undisturbed soil, medium to higher amplitude reflections (white, yellow and green) are produced by soil horizons and remnant foliation in the metamorphic saprolite. These reflections are absent across grave shafts filled with homogenous backfill, which produces a rectangular, reflection-free (blue) anomaly on the depth slices. These rectangular, blue anomalies are interpreted as graves if they are the size of a grave and show a pattern of rows or occur in groups.

The African American tradition of grave vaulting, a common vernacular burial type in the 19th and early 20th century, produces a grave shaft with a smaller crypt or burial chamber in the base of the shaft that is large enough to place a coffin or body (Davidson, 2012). Wooden planks rested on an earthen shelf around the perimeter of this lower chamber. The purpose of the planks was to prevent soil from coming in direct contact with the coffin (Davidson, 2012). The earthen shelf could produce a reflection within the grave shaft even after the wood has decayed. In some cases, a stone slab was used in a vaulted grave. This could be identified on GPR profiles as a high amplitude reflection or appear as an oblong, high amplitude set of reflections on the depth slice.

Twentieth-century marked burials consist of a rectangular grave shaft with a vault or coffin. The depth of the grave shaft can range from 4 to 6 ft with the top of the coffin or vault at about 2 to 3 ft deep. These burials produce a high amplitude, reflection or hyperbola on GPR profiles (Conyers, 2012). The GPR depth slices show the coffin or vault as a high amplitude (green and yellow) rectangular set of reflections between depths of 2 and 3 ft.

Each of the anomalies flagged in the field was carefully examined with the criteria for unmarked burials in mind. This resulted in fewer potential graves being designated than in the initial field survey. The length and orientation of each identified burial were recorded.

5 RESULTS

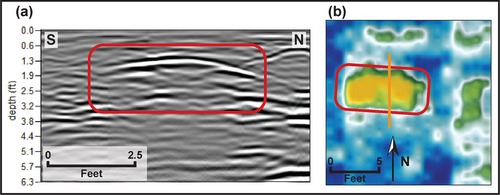

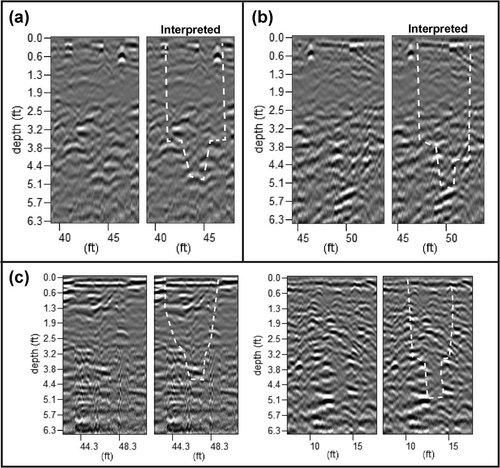

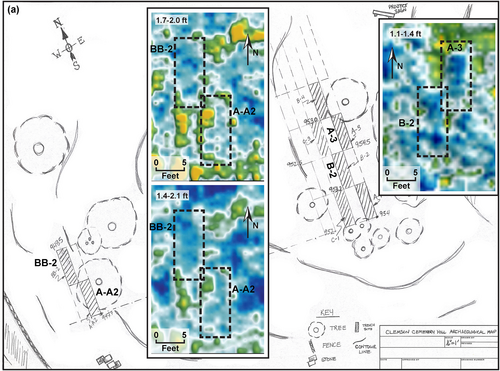

Marked burials within the 20th-century Woodland Cemetery are clearly identified in the GPR data at the location indicated by headstones (Fiedler et al., 2009). These burials produce high-amplitude, broad hyperbola where the transect crosses perpendicular to the grave shaft (Figure 4a). On the GPR depth slices, marked burials appear as high amplitude (green and yellow) rectangular sets of reflections between depths of 2 and 3 ft (Figure 4b).

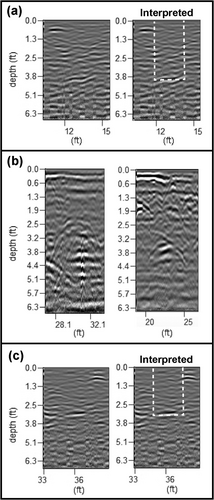

A total of 534 anomalies that potentially represent unmarked graves were identified. The grid data were used to confirm the GPR signature of potential burials initially identified in the field at 334 of the flagged anomalies. An additional 200 potential graves identified on field transects were located on the surrounding slopes. The steep slopes and vegetation were obstacles that prevented collecting grids and verifying the GPR signature of these burials. Anomalies representing unmarked burials were identified by shallow truncated reflections, reflections off the walls of the grave shaft and reflections at depth (Figure 5a). Where the base of the grave shaft could be observed, it was represented by a hyperbola, a horizontal reflection, or a point reflection (Table 1). Hyperbolic reflections are caused by coffins, the void space they enclose and sufficiently large buried artefacts (Conyers, 2012) (Figure 5b). The horizontal reflections are interpreted as a relatively level, horizontal floor in the bottom of the grave shaft (Figure 5c). A narrow, point reflection indicates the possibility of a smaller chamber or crypt excavated within the base of the grave shaft (Figure 6).

| GPR reflection characteristics | % of graves | |

|---|---|---|

| Truncated reflections at the top of the shaft indicating shallow soil disturbance | 31.7% | |

| Reflections along the walls of the shaft | 85.8% | |

| Reflection-free anomaly on the GPR depth slices | 35.8% | |

| Characteristics indicative of burial type | ||

| Coffin/burial remains | Hyperbola at base of shaft | 12.5% |

| Shaft burial | Horizontal reflection at base of shaft | 19.2% |

| Chambered burial | Chaotic reflections in base of grave shaft | 27.5% |

| Point reflection at base of shaft | 43.3% | |

| Stone vaulted | A high amplitude reflection across shaft | 11.7% |

- Note: Frequency percent based on 120 burials identified on the western slope of Cemetery Hill and also shown in Figure 11.

A subset of 120 unmarked burials located within the level gridded area on the western slope were categorized as having a horizontal base, chambered, or vaulted with stone slab based on five reflection characteristics (Table 1). To be certain that the reflections observed were indicative of burial practices, grids in areas with shallow bedrock and rocky soils were avoided.

The most common characteristic (86%) observed in the unmarked burials was reflections along the walls of the grave shafts (Table 1). A reflection off the base of the grave shaft was observed in 75% of the burials. Evidence for a grave shaft with a level, horizontal floor (horizontal reflection) was observed in about 19% of the graves. Chaotic reflections and/or point reflections in the base of the grave shaft were observed in 27% to 43% of the burials. These reflection characteristics could indicate a chambered burial. A high amplitude reflection across the grave shaft was observed in 12% of the burials (Table 1).

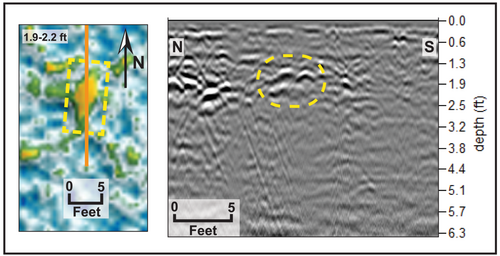

The clearest sets of reflections representing chambered burials include subtle reflections off the earthen shelves at the top of the crypt and a narrow reflection in the centre of the grave below (Figure 6a,b). Many of these vaulted graves are more difficult to interpret as they are represented by discontinuous, chaotic reflections (truncated and disorganized) in the lower grave shaft and a point reflection off the base of the burial chamber (Figure 6c). Chaotic reflections are likely produced as the radar reflects off of multiple surfaces in a small area. A smaller chamber at the base of the shaft is indicated as the width of the area of chaotic reflections narrows at depth. Unmarked vaulted burials with stone slabs appear as high amplitude reflections on the GPR profiles and as oblong, high amplitude reflections between depths of 3–4 ft on the GPR slices (Figure 7). They tend to be smaller and deeper than the reflections produced by the vaults and coffins in marked 20th-century burials.

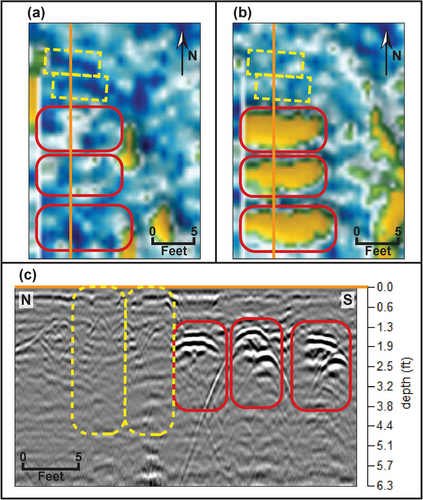

Rectangular, reflection-free (blue) anomalies on GPR depth slices were observed only at 36% of the unmarked burials (Figure 8a). These reflection-free anomalies are produced by the homogenous backfill in the grave shaft. Many of the GPR transects imaged rows of anomalies characteristic of potential unmarked graves on the western slope (Figure 8b). Evaluation of both the transect and slice data was necessary because marked burials were juxtaposed within the rows of unmarked burials (Figure 9a–c).

5.1 Distribution of unmarked graves

Many potential unmarked graves were juxtaposed with marked graves within the grid data (Figure 10). The recorded burials in Woodland Cemetery encircle the Calhoun Family plot (square grid in centre of map; Figure 10). In addition to the marked burials imaged as high-amplitude reflections, there are multiple anomalies (shown in blue) consistent with unmarked graves in the western half of this plot (Figure 10). The modern cemetery extends to the northeast from the Calhoun plot. Here, anomalies believed to represent unmarked graves were identified from within open areas including under the paved roadway and within the aisles between modern burial plots (Figure 10). The northwest section contains a significant number of unmarked graves that extend to the edge of the parking lot excavation. The southwest section contains most of the previously reported slave cemetery. This area has one of the highest concentrations of potential unmarked burials.

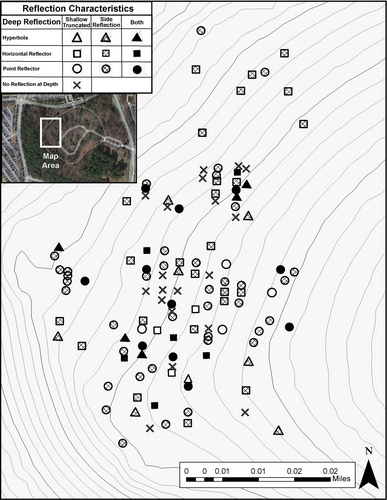

Thicker soils within the grids surveyed on the western slope allow us to map the reflection characteristics used to identify potential unmarked graves (Figure 11). Vaulted graves with chambers at their bases are shown as point reflectors (circles). Hyperbola may indicate burials with wooden caskets or other objects (triangles) and graves with simple horizontal bases occur (squares). Graves with similar characteristics appear to occur in groups suggesting a relationship to temporal or cultural burial practices (Figure 11).

Archaeology excavations by Cowan-Ricks and her students are imaged within the gridded data to the west of the Calhoun plot (Figure 12). The GPR depth slices did not show anomalies characteristic of unmarked burials in the vicinity of these trenches.

5.2 Orientation and length of potential unmarked graves

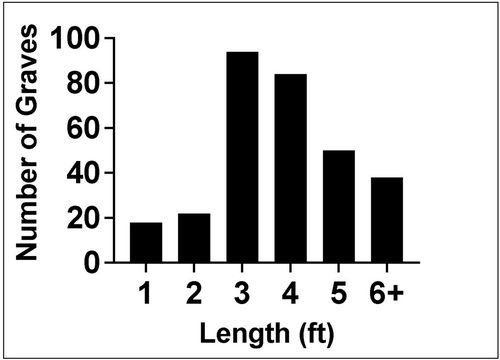

The anomalies indicative of unmarked graves are aligned with their length generally in the east–west direction regardless of topography and location within the cemetery. The length of the grave shaft for 306 of the burials occurring within the gridded survey area was measured based on the number of 1-ft spaced transects where the GPR anomaly was detected. The burial shafts could be slightly longer than the indicated length; therefore, the length should be considered a minimum. Shaft lengths were recorded as whole integers (Figure 13). The most common lengths were 3 and 4 ft (58%), followed by 5 and 6+ ft (28%). Only 13% were shorter grave shaft lengths of 1 to 2 ft.

6 DISCUSSION

The Clemson Board of Trustees initiated the collection of high-quality GPR data that imaged 534 GPR anomalies indicative of potential unmarked graves within Cemetery Hill; 334 of these occur within the modern Woodland Cemetery and were interpreted from depth slices and on GPR profiles. Two hundred potential graves occur on the surrounding slopes and were identified from GPR profiles. The unequivocal evidence of unmarked burials on Cemetery Hill is as important for the modern-day Clemson University community as it is for the descendants of those buried here. A full accounting of the unmarked African American graves in the Woodland Cemetery adds supporting information for the ‘Call My Name’ Project directed by Dr. Rhondda Thomas at Clemson University (https://callmyname.org). This project seeks to identify and document the lives of African Americans associated with Clemson University who were enslaved, convicted laborers, sharecroppers, domestic workers, tenant farmers, wage workers and their families. Some of these people have their final resting place within this cemetery. We were also able to image the location of the excavations conducted by Cowan-Ricks and her students (Figure 12) and place them in context with the unmarked graves that she was seeking. In addition, the Woodland Cemetery and African American Burial Ground Historic Preservation Project (www.clemson.edu/cemetery) has engaged Clemson students and faculty to document the history and meaning of this sacred place. Availability as a website increases its relevance to descendant communities and the public (Rainville, 2009). In 2021, a research symposium, ‘Historic Cemeteries and the University: The Power of Place and Community’ was held virtually to engage academic scholars, community members and professionals in this topic.

6.1 Number and distribution of unmarked graves

Many of the plots within Woodland Cemetery are filled with the maximum number of modern burials allowed for their size, and much of the surrounding soil was disturbed by excavations for these burials. However, potential unmarked graves were identified under Woodland Drive, Cemetery Way, and in the aisles between the plots (Figure 10). Based on the number and distribution of these burials, it is likely that unmarked graves were located in some of the plots where modern burials now lie. The operation of Woodland Cemetery has been modified to respect the presence of the unmarked burials, resulting in prohibition of vehicle traffic within the cemetery and in hand digging of future graves in the presence of an archaeologist (Clemson University Board of Trustees, 2022). Although Clemson University intends to honour pending burial plot reservations gifted to the families of faculty and staff members, as of 21 October 2022, they have required a review of the GPR data before approving locations for new burials.

The GPR survey detected potential unmarked graves on the slopes where there are few modern burials allowing their presence to be clearly observed. The western slope may have been used as an African American burial ground because it was near the Seneca River (Figure 1). This is in keeping with the belief that the souls of the enslaved could use nearby waterways to return to Africa (Carwile, 2008; Thomas, 2020). Also, the western slope would have been hidden from the view of the 2-story antebellum plantation house and gardens located northeast of Cemetery Hill. On the north-western slope between Cemetery Way and Press Road, the slope is not as steep as other portions of the site, making it easier to access in the 19th century by people digging graves by hand (Figure 10). The distribution of graves appears to extend to the edge of the hill on the northern and western slopes suggesting that an unknown number of African American burials were lost as the slopes were cut away in the 1960's and 70's.

In the 19th century, it was common for plantation owners to establish a family cemetery on the crest of the hill near their home and the first recorded burial in 1837 is attributed to the Andrew P. Calhoun family. Twelve unmarked graves discovered within the Calhoun plot were hilltop burials before the Calhoun plot was delineated and fenced sometime in the 1960s according to available aerial photographs. Based on the earliest historical records, domestic and agricultural enslaved people were owned by James McElheny at Clergy Hall in 1803, before the house was acquired by the Calhoun family and enlarged by enslaved people into the plantation house (Schroer, 1975; Thomas, 2020).

6.2 GPR evidence for an African American burial ground

Although no records have been located to determine the identity of individuals, their interment in an east–west orientation is common for individuals buried following Christian tradition (Eriquez, 2009; Perry et al., 2006). In addition, we detected GPR reflections at the base of the grave shafts that suggest variability in burial types (Figure 11). These may be related to the time period of the burial or the social status at the time of an individual's death. For example, 19% of unmarked grave anomalies are recorded with a horizontal reflection resulting from decay of the wooden coffin in a flat-bottomed grave shaft (Figure 11). These graves may represent the earliest burials of enslaved or convicted people, or children. Up to 50% of the anomalies had reflections that were consistent with a chambered or vaulted grave. Of these, 12% detected a stone slab above the burial chamber and the rest were possibly vaulted with wooden planks. This practice was common in 19th- and early 20th-century African American burials in the United States (Davidson, 2012). The 12% of stone vaulted burials is greater than was initially identified in the field as the detailed analysis of reflections for this study recognized more subtle evidence of stone vaults. However, an archaeological excavation would be necessary to ground truth these interpretations. A hyperbola was observed in the grave shaft of 13% of unmarked graves. It is expected that wooden coffins or remains of the formerly enslaved population would have decayed; however, those from more recent burials could be present. Identification of graves in rows without overlap indicates the presence of a sacred burial ground that must have had grave markers when it was actively used and perhaps an oral history related to the use of this space over more than a hundred years.

6.3 Demographic evidence from GPR data

Length data from the GPR survey are a proxy measure for the size of the burial container, which may be used to estimate the age of individuals at the time of death because African Americans are laid to rest in an extended supine body position (Perry et al., 2006). We consider this an estimate because post-depositional processes such as bioturbation could alter the appearance of the grave shaft. The most common burial lengths fall within 3–4 ft and were likely graves of adolescents or small adults. This may reflect the large number of enslaved women and children as well as the presence of convicted laborers most who were under the age of 25 (Thomas, 2020). Adults are represented by burials 5–6+ ft in length, which make up 28%. Infants and small children (<3 ft in length) account for 13% of the graves, supporting the high rates of infant mortality (exceeding 50%) in enslaved populations (Blakey, 2001).

7 CONCLUSIONS

A high-quality GPR survey has been used to identify the location of 534 possible unmarked graves establishing the presence of an African American burial ground on the site of Woodland Cemetery on the campus of Clemson University, a public university in South Carolina. These data support historical research begun by archaeologist Carrel Cowan-Ricks in the early 1990s and the ongoing ‘Call my Name’ Project at Clemson University that seeks to document contributions by enslaved African Americans and their descendants, and convicted laborers many of whom were buried here (Thomas, 2020). In addition, the discovery of potential unmarked graves juxtaposed within the modern burial plots of Woodland Cemetery has resulted in modification of the cemetery operating policies in order to respect the sacred ground and not to disturb any unmarked burials in the future.

The GPR survey included collecting both profiles from the sloping hillsides and a 5-acre grided area within the modern cemetery. Unmarked graves from the 19th to early 20th century were identified as shaft burials and burials vaulted with stone and possibly wooden planks. Hyperbolic reflections in 13% of graves indicate the presence of a large reflector such as a coffin or other artefact. Vaulting as well as the east–west orientation of graves are consistent with African American burials (Davidson, 2012; Perry et al., 2006). Variation in styles may indicate burial during several periods in history or variable social status. The organized pattern of rows and groups suggests that the graves were originally marked as in a community cemetery and respected as a sacred burial ground. Grave length data were estimated from the number of transects that crossed the shaft and suggest that 58% of the burials were adolescents or small adults, 28% were adults and 13% were infants and children. This is consistent with the enslaved population as well as the occurrence of illnesses during the period that the burial ground was in use.

This GPR survey documents the overlap of the African American burial grounds by the modern Woodland Cemetery that includes more than 600 marked graves of white employees and dignitaries affiliated with Clemson University. Previous attempts made by Carrel Cowan-Ricks and others to call attention to the pre-existing burial grounds were not fully supported by the University. Current students and public opinion have demanded that public Universities account for past practices. This has resulted in detection, mapping and analyses of the unmarked graves that comprise the African American burial grounds on Cemetery Hill. This is a necessary first step in respecting the marginalized people who significantly contributed to the success of Fort Hill Plantation and the construction and maintenance of Clemson University.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Clemson University, Sally Mauldin and Rick Owens, Campus Preservation Officer, who facilitated the field work. We appreciate additional help from James Bostic in the field and drafting and GIS support from Brooke Steenwyk and Alex Zacher. We appreciate comments from Dr. Rhondda Thomas, Clemson University, on a draft of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The GPR data that support the findings of this study may be requested from Clemson University.