Local child protection in the Philippines: A case study of actors, processes and key risks for children

Abstract

This article explores the child protection actors, processes and child maltreatment issues in a regional Local Government Unit in the Philippines. Utilising a qualitative case study design, it engages with 14 young people with histories of child maltreatment and 13 key child protection actors, exploring their views and experiences of child protection actions, processes and outcomes. The findings highlight informal community-based actors, including neighbours, family, friends and non-government organisations in initial responses to child maltreatment, compared to formal child protection actors, who respond to severe maltreatment utilising a legal framework. Actors are constrained by limited government capacity and community reach, revealing misalignment between formal child protection activities and breadth of risks for children. Non-government organisations assist child protection efforts through the provision of residential care. Policy recommendations include strengthening relationships between formal actors and communities, expanding early intervention activities, and developing the capacity of community-based child protection actors.

1 INTRODUCTION

This study investigates local level actors, functions and processes that work to protect children, and respond to child maltreatment in the Philippines. The need for localised and contextual analysis of child protection in the Philippines is strong, given recent analysis of national child protection policies and systems identified an absence of information, research and analysis of child protection (Roche, 2019). Additionally, approaches to improving child protection systems often focus on formal structures and government-managed services, which can ignore the informal, community-based child protection efforts of communities and families (Wessells, 2015), and disregard the low utilisation rates of child protection systems in the Global South (Wessells et al., 2012).

In response, this study explores child protection practices in one Local Government Unit (LGU) in the Central Visayas of the Philippines via a case study design, highlighting child protection actors and their functions. It focuses on child protection from local perspectives, aiming to better understand the role, interactions and influence of NGOs, including residential care, as components of wider child protection approaches. This is important given that the over-reliance on the institutional care of children—in residential care, orphanages, group homes and other settings—is a major component of approaches to children's welfare and protection in the Philippines. Despite this, its connection to child protection practices, formal or otherwise, is yet to be explored.

The focus of this study is significant given major risks to children's well-being in the Philippines (Roche, 2017). Emotional and psychological abuse is extensive, including corporal punishment and family violence (Sanapo & Nakamura, 2011) with children's exposure to violence widespread (Hassan et al., 2004). Child sexual abuse remains under-investigated despite evidence that 17.1% of children over the age of 13 have experienced such violence (Council for the Welfare of Children [CWC] & UNICEF, 2016). Children also navigate major safety risks including commercial sexual exploitation, child labour, extrajudicial killings and armed conflict (Daly et al., 2015; Mapp & Gabel, 2017). The frequency and severity of child maltreatment is impacted by major structural disadvantage and the risks these engender (Pells, 2012). This is relevant to the Philippines given an estimated 31.4% of children in the Philippines live in poverty (Philippine Statistics Authority [PSA], 2017); and 13.4 million children are considered income poor, while 5.9 million live below the ‘food poverty line’ (PSA & UNICEF, 2015).

1.1 Child protection in the Global South

UNICEF understands child protection as preventing and responding to violence, exploitation and abuse (UNICEF, 2008), an approach largely utilised within system-based frameworks in Global South policy contexts (Connolly et al., 2014). Child protection systems aim to provide a coherent structure, including a combination of policy, programs and efforts, to prevent, respond and resolve child maltreatment (Pells, 2012; Wessells et al., 2012). As such, they seek to integrate fragmented programs and actors across community, national and international levels (Wulczyn et al., 2010). Community-based child protection has emerged in circumstances of ineffective or absent child protection systems and diverse populations, often comprising local level groups, actors or processes that prevent or respond to child maltreatment in the absence of effective formal structures to protect children (Connolly et al., 2014; Wessells, 2015; Wessells et al., 2012). These approaches utilise community strengths and actors, may incorporate community-government collaborations (Wessells, 2015), and require trust across micro- and macro-levels with numerous and diverse actors and groups (O'Leary et al., 2015). The primary advantage of such approaches is that child protection actors are closer to the lives of children and their families and the contexts in which maltreatment occurs.

1.2 Child protection in the Philippines

The Philippines’ current child protection system is described as ‘top-down’, with clear legislation and national policy that is poorly implemented to the point that its ‘systemic’ characteristics are questioned (Roche et al., 2021; UNICEF, 2016). Child protection coverage varies significantly in resources and approaches, while social welfare infrastructure lacks capacity and technical expertise (Kim & Yoo, 2015; Ramesh, 2014; UNICEF, 2016). The Special Protection of Children Against Abuse, Exploitation and Discrimination Act (Republic Act 7610) provides a legal basis to protect children from abuse including ‘neglect, cruelty, exploitation and discrimination and other conditions, prejudicial to their development’. The Act also states that it is the ‘policy of the State to provide special protection to children from all forms of abuse’ and to ‘carry out a program for prevention and deterrence of and crisis intervention in situations of child abuse, exploitation and discrimination’, detailing a legislative and programmatic commitment to protecting children.1

Child protection, and broader welfare approaches, reflect wider governance structures in the Philippines. The state provides minimal social assistance, with the family unit taking onus for its own welfare, under the ‘productivist’ conditions of the Philippine welfare state, whereby economic growth is prioritised over social policies (Choi, 2012; Yu, 2013). National policy highlights the role of local government as a central component of welfare interventions for children (CWC, 2010), while emphasising parents’ and families’ own responsibilities for protecting children (Roche, 2019). LGUs struggle to provide services and can leave communities without basic services and facilities (Yilmaz & Venugopal, 2013). Further, weak national institutions struggle to hold local governments to account (Yilmaz & Venugopal, 2013), creating situations whereby child protection efforts have become discretionary, impacting welfare services for children and families. Emerging from these governance conditions are an array of non-government welfare organisations, including residential care settings. The Philippines’ Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) lists over 900 private social welfare agencies with residential care programs (DSWD, 2021a, 2021b); however, there are generally thought to be many more (Graff, 2018), due to limited regulation and the international commodification of children's welfare and demand for engagement with orphans (Cheney & Ucembe, 2019). How these factors contribute to local child protection arrangements, child protection actors and their roles and functions, including the role of residential care, is the focus of this study.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 details the study's case study research design, as well as its participants, ethical arrangements, and approaches to data collection and analysis. The findings are then presented in Section 3, exploring the harms and safety risks for children and identifying key child protection actors and processes in the LGU. Following this, Section 4 discusses a misalignment between child protection efforts and the intersecting experiences of child maltreatment at the community level. Section 5 concludes.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Research design overview

This study utilises an exploratory, interpretive case study design, considered ‘an intensive, holistic description and analysis of a single entity, phenomenon, or social unit’ (Merriam, 1998, p. 34). In interpretive case study design, social phenomena, in this case child protection, is understood through the interpretations of participant actors (Martin, 1993; Sheikh & Porter, 2010), focusing on ‘localised understanding’, and exploring experiences, practices and lived realities (Cooper & White, 2012, p. 18). This requires investigating a phenomenon that occurs in a bounded context, providing a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (Merriam, 1998). In this case the phenomenon is child protection, and the boundary is an LGU in a regional area in the Central Visayas of the Philippines, with a population of around 130,000, focusing on the child protection processes and functions within its boundaries. It takes an exploratory objective, aiming to provide an overview of child protection, revealing its practices and characteristics, while describing the context in which they are exercised, and identifying areas to improve child protection. It is hoped that this research design can offer policymakers insights into the local level impacts of policy decisions, and contribute to the development of children's welfare policy and practice in the Philippines.

2.2 Study participants

The case study investigates child protection from the perspectives of 27 participants, summarised in Table 1. Participants include a range of child protection actors such as program managers, government officials and employees, and social workers, as well as children and young people, residing or previously residing in a residential care setting, who have experienced maltreatment and, as a result, child protection practices.

| Participant category | Context | Detail | Total (n = 27) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children and young people with experience of maltreatment | Current or previous experience of living in a residential care setting in the LGU. | Living in residential care (n = 10). Age range 15 to 22 years old, average age 16.4. | 14 |

| Previously living in residential care (n = 4). Age range 22 to 29 years old, average age 24.2. | |||

| Child protection actors (NGOs) | Residential care programs (n = 5) | Program managers (n = 3) | 7 |

| Child Protection Unit (n = 1) | Social workers (n = 3) | ||

| Violence against women and children advocacy organisation (n = 1) | Advocate (n = 1) | ||

| Child protection actors (government officials and program staff) | Department of Social Welfare and Development (n = 1) | Welfare program manager (n = 1) | 6 |

| Residential care program (n = 3) | Residential care program manager (n = 2) | ||

| Government official (n = 1) | Residential care social worker (n = 1) | ||

| Philippine National Police (n = 1) | Mayor and Chair of the Local Council for the Protection of Children (n = 1) | ||

| Police Investigator (Women and Children's Desk) (n = 1) |

- Abbreviations: LGU, Local Government Unit; NGOs, non-government organisations.

Thirteen participants represent a range of government and non-government organisations (NGOs) and groups, comprising positions that respond to and act to prevent child maltreatment in the LGU. The non-government programs represented include two residential care settings, a Child Protection Unit (CPU), and a family violence advocacy organisation, while the government-based participants represent residential programs, police, the local DSWD and the chair of the Local Council for the Protection of Children.

Data from interviews with 14 young people are included in this article. All young people had experiences of child maltreatment, and were recruited from four residential care programs based at one large NGO. To participate, children and young people had to be 15 years of age or over, have resided in residential care for a minimum of 6 months, or previously lived in residential care for a minimum of 6 months. Of the participants, six were female and eight were male, and at the time of interview, 10 lived in residential care, while four had previously lived in residential care.

2.3 Ethics

This study gained clearance from the University's Human Research Ethics Committee. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Children and young people also underwent an assent process, whereby a verbal agreement to participate was ascertained (Kendrick et al., 2008), and the principles of research participation, including non-compulsory participation, confidentiality, the ability to withdraw participation at any time, and how information would be used, were discussed. Verbal permission from children and young people's carers was provided. Consent processes with children and young people were conducted independently of carers to minimise potential for coercion. Written and verbal information about the study was provided to children and young people in both English and Visayan. A female interpreter was present for all interviews; English was spoken for the majority of interviews. All interviews with child protection actors were conducted in English without an interpreter. Risks for children were mitigated by the choices they were afforded around their participation, including the time and place of interview, audio recording, and the option of having a support person in the interview. Children were clearly informed and reminded of the non-compulsory dimension of the interview, their choice and control around discussion topics, and that they could withdraw at any time. Support persons were made available to participants if they wanted. The identities of participants were protected in this study through the use of participant identifiers rather than names in interview notes and records.

2.4 Data collection

Data collection was undertaken between October and December 2018. Child protection actors were recruited using a snowballing technique (Bryman, 2016), starting with participants in the researchers’ professional network. Those participants subsequently suggested further potential respondents, drawing on their expertise and knowledge of child protection networks in the LGU; these people were either contacted directly, or introduced to the researcher. Children and young people were recruited through a convenience sampling strategy (Bryman, 2016). The researcher utilised a prior professional relationship with the NGO from which children and young people were recruited. Social workers at the NGO disseminated information to prospective participants, who then informed either the social worker or the researcher of their interest in participating.

Qualitative methods were chosen for their potential to provide detailed insights and interpretation (Merriam, 1998). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with all participants with interviews lasting between 20 and 90 minutes. The researcher also recorded field notes, focusing on their impressions, reactions and reflections to interviews. The interviews with child protection actors focused on their primary role and responsibilities, their work background, history and expertise, as well as current circumstances of child protection practices, including processes, decision-making, responses and prevention, and linkages between other child protection actors. Their views of child maltreatment issues and challenges, and ways to improve child protection in the LGU were also discussed. The interviews with children and young people explored their life histories, transitions into residential care and their views of residential care, as part of a broader study on residential care in the Philippines. A more detailed analysis of their life histories is published in Roche (2020). In recounting their life histories, 14 participants detailed experiences of maltreatment, and the child protection responses that occurred. Discussions about maltreatment arose out of children's accounts of their lives, with children given the opportunity to direct and control the conversation, including the level of detail they provided. This approach, within the broader ethical arrangements of the study, ensured that no participants became distressed in interviews.

2.5 Data analysis

Despite diversity in definitions of abuse and neglect, particularly in circumstances where structural inequalities and poverty impact on children's welfare (Roche, 2020; Walker-Simpson, 2017), for the purposes of analysis, this study utilises the World Health Organization's (2006, p. 9) definition of child maltreatment. Audio files were transcribed verbatim and subsequently uploaded into NVivo software for analysis. The interviews were read through and the researcher identified emerging patterns, themes and consistent categories across relevant passages of text. The analysis focused on participant accounts and interpretations of child protection actors, processes and perspectives on improving child protection in the community; it was confined to information within the boundaries of the case study. The validity of the analysis is supported by discussions with national child protection experts in the Philippines after data collection in the case study site, reflective discussions with colleagues, and the researcher's prolonged engagement in the field. While the findings of this case study are limited to the child protection structures and practices in the study site, and cannot necessarily be generalised to other LGUs in the Philippines, the findings can add to the broader knowledge of child protection practices that have emerged in the policy and welfare conditions of the Philippines more broadly.

3 FINDINGS

3.1 Views of harms and safety risks for children

We have financial problems so my parents end up fighting each other … Sometimes physical, sometimes verbal … They hit me … [and] sometimes my father would also hit my mother and the [other] children … [We were hit] with hands sometimes or a bamboo stick … (PIRCM5)

I have a stepmother and she always punished me … strong pinch and hitting … emotionally I feel that no one loves me because my father is also out, that's why she can hit me … I do the same as my brother, he escaped, that's why I escaped. (IRCM8)

We have dysfunctional families wherein … economic status is very unstable. It is either the mother who doesn't have work or the father who doesn't have work. So the children that are involved, they cannot go to school, [the parents] cannot supply the needs of the children, even the very basic needs, the food. (PPS5)

We cater for physical abuse, but sexual abuse is more serious … The most vulnerable children are 8 to 12 [years old] and mostly the perpetrators are coming from the family, it's an incest case … Father, grandfather, uncle, cousins and sometimes there are non-family members like neighbours, boyfriend. (PPS8)

There was overall agreement among children's and child protection actors’ accounts about what constituted harm or maltreatment and the major risks to children. While forms of child exploitation such as child labour were apparent, this was not a major concern, given the subsistence farming involved in many families’ lives, and the desperate need for income.

3.2 Child protection actors

3.2.1 Community-based child protection actors

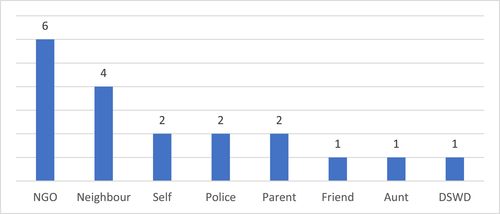

Participants identified a range of community-based actors undertaking informal child protection activities. These included community members and family without an organised child protection role, function or expertise, who intervened in scenarios of child maltreatment, and welfare organisations that sit outside formal child protection arrangements. Young people identified initial primary actors (in some cases multiple actors) assisting them when harmed. Their accounts detail the first actors to intervene in circumstances of abuse and neglect, shown in Figure 1. In these circumstances, intervening actors often included neighbours, parents, friends or in one case an aunt. Figure 1 does not include scenarios in which no initial assistance was rendered.

Child protection actors for children and young people living in residential care. DSWD, Department of Social Welfare and Development; NGO, non-government organisation

The guy threatened me not to say anything, so the guy continued doing things with me until I got pregnant … my aunts noticed and brought me to the police … The social worker and my aunts decided to put me [into a residential care program]. (IRCF10)

There is a concerned citizen which happens to be in the community where I lived, our neighbour, who apparently went to [NGO residential care] because she saw our mother always leave us. She reported it to [the NGO residential care program]. (IRCM10)

My neighbour brought me here because he said [NGO residential care] is a good place to live. They didn't accept me right away, it's the following day when we go back that I was accepted. (IRCM6)

The informal actors identified by participants highlight individualised and informal responses to child maltreatment, identifying children at risk, and then intervening. NGOs play a similar role in responding to child maltreatment. Families could be known to welfare NGOs which offer assistance to children in an outreach-type capacity. For example, when a participant (PIRCM5) experienced family violence in his home, his brother was already living at an NGO residential care program and the participant was also moved by the NGO into that program. In some circumstances, NGOs took an outreach-type approach and brought children into their program. For a man previously living in residential care (PIRCM1), who had run away from home as a child due to violence, and another man previously in residential care (PIRCM6) who had experienced corporal punishment in the home, a representative of a non-government residential care program offered to care for them. NGOs were also known to children, with a participant (IRCM8) describing running away from home to an NGO due to corporal punishment. These examples demonstrate non-government residential care providers as established community-based actors, an important child protection mechanism, despite no formal child protection role. The wishes of children in these scenarios are unclear, and may risk circumstances whereby children are placed in residential care against their wishes, rather than support families to provide a safe environment.

3.2.2 Formal child protection actors

In our [child protection] settings, we prefer to go to the police station first because they [the children] can feel safe and secure there. (PPS8)

The CPU started with nothing because it's all donated by the [private foundation], not by the government … The idea [for the CPU] came from the private sector and the [foundation] is going over to the CPU to make it functional, but I don't know why the government did not think to have a program like this. (PPS8)

As much as possible we want to be community based and within the context of a family, intervene there. But you know, when the situation requires it, residential care is important and you can say what you want about the negatives of residential care, but it's sometimes just necessary. (PPS16)

In scenarios of child maltreatment, the DSWD, with social workers working across a number of communities in the LGU, undertake family risk assessments, refer clients to police, and provide material assistance to families where possible. While none of the young people who participated discussed the role of Barangay officials (voluntary members of the lowest administrative level of governance in the Philippines), in responding to their maltreatment, child protection actors described that their role can involve reporting family violence or other harms to the DSWD or police via a Barangay Protection Order.

3.3 Child protection processes in the LGU

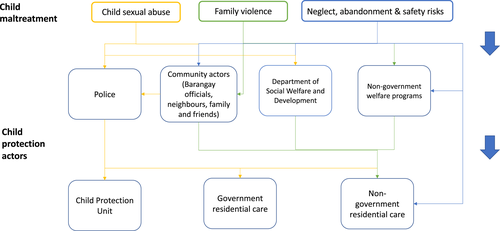

Child protection actors provided their interpretations of the key actors and processes in the LGU. Figure 2 details the actors, their relationship to child maltreatment incidents, and the processes in which actors are typically engaged in circumstances of child maltreatment. The colours show the actors that are engaged for types of child maltreatment, and the direction in which they proceed through actors.

Child protection actors and processes

Child protection actors' accounts of child protection processes highlight that cases of child sexual abuse and significant family violence are far more likely to engage formal child protection actors, than harms relating to physical abuse and neglect. The formal actors rely on non-government actors, who take on significant components of the overall child protection effort in the LGU.

3.3.1 Child sexual abuse

The victim was the middle child and the older sister told the neighbour and the neighbour told the Barangay official, then the Barangay official reported it to the social worker [DSWD], and they reported it to us. (PPS14)

If we have a child sexual abuse case in [LGU], I have to convene the multidisciplinary team, the doctor and the police officer to conduct a forensic interview and forensic examination of the child sexual abuse case … after interviewing the child, we will examine the child in that room … And after examining, we will conduct planning for the family. If the perpetrator is within the family, we directly remove the child from the family. (PPS8)

If the child is below 15 and it's not possible to be reunited with their family, as there is no supportive family, she will be at risk if she goes back to the family. (PPS10)

3.3.2 Family violence

-

Participant: We do the work in filing the case, we do everything. If we look at this case as severe, and it is no longer beneficial to allow the wife to go home, and we have legally arrested the husband, we call the prosecutor's office and ask for guidance from an Attorney.

-

Researcher: How do you judge if it is severe enough to go ahead?

-

Participant: If it is repetitive, like three, four times. (PPS14)

The crucial role of police as primary child protection actors means that there is a high threshold for reporting maltreatment, a reporting process that may be inaccessible for some, potentially resulting in the underreporting of less serious maltreatment issues.

3.3.3 Neglect, abandonment and safety risks

Actually they [residential care programs] are of great help to us, especially in times of emergency. Like, for example, we had a boy who was physically abused by his mother, and left alone in the city. The mother refused to take him back … So the child should be placed in a safe place, we go directly to [NGO residential care] for help. (PPS5)

They meet the needs that the DSWD cannot provide … [NGO residential care] are a partner, they will never say no to a child. If there's a will, there's a way. (PPS5)

If I will found [sic] out that she is not safe, I will accept. I will strongly recommend to our council that … [we] accept this girl. (PPS12)

Shelters are one of the biggest contributions, especially for children that have nowhere to go … We try to fill in the gap of what the government cannot do, although [children's welfare] is supposed to be their biggest priority, but that is something we have no control over … If government will not fill the need, what else can we do with these children? Where are they going to go? (PPS15)

4 DISCUSSION

The findings show that formal child protection actors are limited to responding to severe child maltreatment, assisting primarily within a legal framework, despite national legislation outlining requirements for government-led child protection programming. Police and the local DSWD are important formal child protection actors, and are responsive to severe forms of abuse, but provide mostly a secondary role in broader child protection activities such as identification or early intervention. These findings show the limitations of formal child protection efforts, which have given rise to a local hybrid government, non-government and localised community-based child protection system. Community-based child protection actors, including community members and family, provide informal and individualised responses to child maltreatment and risks, identifying children at risk and assisting them to safety, while these efforts are supported by NGOs. The utility of these community-level actors is likely due to their proximity to incidents of maltreatment and established community-based caring systems.

The findings reveal misalignment between formal child protection activities and local views of major harms to children. Formal actors are responsive to severe maltreatment, but are unlikely to intervene around lesser harms pertaining to neglect or family violence, common to the community. These findings raise concerns about gaps in child protection efforts in the LGU, and the broader functionality of the Philippines’ child protection system. Formal, government-funded child protection actors lack community reach, as well as the resources, flexibility and capacity needed to respond to and prevent the range of child maltreatment present in the LGU. Accordingly, residential care plays a crucial role in local child protection activities, serving as the only alternative care option for children. This is problematic given the potential harms of institutional care for children (McCall, 2013), and reveals an overreliance on residential care as a child protection model similar to other Global South settings (Chege & Ucembe, 2020). It indicates potential issues around the choices provided to children, the possibility of children being placed in residential care instead of supporting families to provide a safe environment, and a problematic degree of adult decision-making. Facilitating the needs, wishes and participation of children in child protection scenarios is essential (Woodman et al., 2018). Support for further community-driven child protection approaches, linking formal and informal actors is an important next step to align child protection mechanisms, and improve coverage and responsivity. Additionally, national policy and legislation, articulating government responsibility for child protection issues, do not reflect child protection actors and efforts at the local level. Local actors expect more resources and action from government for child protection, a view departing from the long-standing welfare architecture of the Philippines.

Participants stressed the multiple and intersecting experiences of child maltreatment in its various forms, with formal child protection actors unable to respond to all of these concerns. In circumstances such as the Philippines, risks to children's well-being take on broader threats than abuse and neglect, particularly social harms relating to poverty (Walker-Simpson, 2017). Child protection should focus on the key sources of risks to children (Pells, 2012), and thus, in the circumstances of this LGU, respond to the chief concerns of family violence, sexual abuse and neglect and abandonment. It should also work to negate the influence of poverty and inequality on the lives of children, described by Lachman et al. (2002) as ‘extra-familial structural abuse’, which can impact efforts to reduce child maltreatment.

The endogenous elements of child protection in this LGU, such as the privately funded CPU, may not be operating in other LGUs, which may respond differently to child protection issues, with differing actors and levels of resources. However, it can be presumed that other LGUs in the Philippines face a number of similar child maltreatment issues, and primarily draw on criminal justice approaches and local government resources, given the similar governance arrangements and welfare structures across LGUs.

Future research on child protection in the Philippines requires comprehensive investigation into Barangay officials and their role and functionality, given the lack of detail from participants in this study and the literature, and their potential to provide a responsive role in community-based interventions. There is a paucity of research on child protection activities or outcomes, the effectiveness of interventions, and outcomes for children and young people who navigate child protection programming in the Philippines. This study also draws attention to the need for analysis of broader social policy issues and governance in the Philippines, including funding models and budget accountability among LGUs and how these impact service delivery and programming. Additionally, the findings pertaining to child protection processes in this article focus on the evaluations provided by child protection actors, and would benefit from the inclusion of children's perspectives, which is an important area for future research.

5 CONCLUSION

This study presents important, initial understandings of local level child protection in the Philippines, identifying the role, functions and processes of child protection actors and key harms to children in a specific LGU. Participant accounts of child maltreatment highlight diverse maltreatment issues and the need for flexible and responsive child protection actors and processes. The findings outline the importance of informal, community-based child protection actors, and the limitations of formal, government-funded child protection efforts, detailing the LGU's own, endogenous, NGO-supported response to child maltreatment within the resource and governance constraints of the decentralised governance arrangements of the Philippines. The research suggests strengthening child protection efforts should involve formal child protection actors increasing community connections and early intervention efforts, and expanding alternative care beyond residential care programs, while enhancing the capacity of community-based child protection actors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the participants who generously provided their time to this study, as well as Professor Philip Mendes for his valuable support and guidance. This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1 See Special Protection of Children Against Abuse, Exploitation and Discrimination Act, Article 1, Section 2, available at The LawPhil Project, https://www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra1992/ra_7610_1992.html.