Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm managed using resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta with a two-stage approach

Abstract

Background

A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (rAAA) is fatal. While Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) contributes to hemodynamic stability, organ ischemia should be carefully considered.

Case Presentation

A 69-year-old obese man with untreated hypertension presented with sudden back pain and hypotension. Computed tomography confirmed the presence of an rAAA. REBOA was initially planned in Zone 1 via the left brachial artery but was eventually switched to Zone 3 via the right femoral artery. Hemodynamic stability was achieved through blood transfusion and partial REBOA, followed by surgical intervention. The postoperative recovery was uneventful.

Conclusion

Zone 1 REBOA via the left brachial approach provided safe aortic occlusion. Transitioning to Zone 3 REBOA, combined with meticulous organ perfusion management and blood transfusion, prevented ischemia–reperfusion complications.

INTRODUCTION

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (rAAA) is one of the most lethal vascular diseases with a high mortality rate.1 Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is a less invasive aortic occlusion technique for the temporary control of subdiaphragmatic hemorrhage. Prolonged Zone 1 occlusion can cause serious organ ischemia.2 Partial REBOA or Zone 3 (inferior renal artery) occlusion may mitigate ischemic complications.

The femoral artery approach is used in over 95% of cases.3 Although previous case reports investigating rAAA3, 4 reported the use of both femoral and brachial arterial approaches, no studies have validated the superiority of arterial access. The femoral approach requires guiding the REBOA catheter through the aneurysm to Zone 1, potentially increasing the risk of rupture.

Herein, we report a successful case of rAAA managed with REBOA that prevented cardiac arrest and ischemic complications.

CASE PRESENTATION

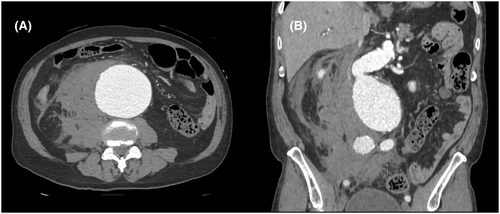

A 69-year-old obese man with untreated hypertension (American Society of Anesthesiologists class IV; weight: 83 kg; height: 179 cm) was admitted due to sudden back pain. Upon admission, the patient had a blood pressure (BP) of 91/73 mmHg, a heart rate of 57 bpm, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. He was alert and oriented. Physical examination revealed an old cholecystectomy scar. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan detected an 8.6-cm rAAA with a retroperitoneal hematoma (Figure 1).

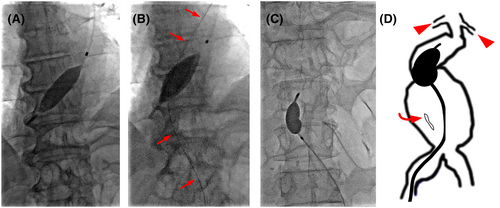

Upon returning to the emergency room, his systolic BP (SBP) dropped to 58 mmHg. After intubation, the patient was transferred to the angiography suite for REBOA. Arterial access was established via the left brachial artery using a 7-Fr sheath (Table 1). Using a 4-Fr pigtail catheter and 0.025-inch guidewire, RESCUE BALLOON®-ER (Tokai Medical Products, Inc., Aichi, Japan) was positioned at the descending aorta. After completing the occlusion of Zone 1 (Figure 2A), the SBP increased to 80 mmHg.

| Time after admission (min) | Resuscitation and hemostasis | Vital signs |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Arrival at the ER | BP: 91/73 mmHg, HR: 57/min |

| 2 | Access to the peripheral vein | |

| 23 | Contrast CT and diagnosed as rAAA | |

| 40 | Decrease in blood pressure | BP: 59/40 mmHg, HR: 45/min |

| 55 | Emergency tracheal intubation | BP: 66/46 mmHg, HR: 86/min |

| 56 | Transfer to the angiography suite | BP: 58/38 mmHg, HR: 62/min |

| 63 | Access to the left brachial artery | |

| 68 | Transfusion of 2 units of pRBC | |

| 70 | Access to the right femoral artery | |

| 85 | REBOA inflation in Zone 1 | SBP: 70–80 mmHg |

| 94 | REBOA inflation in Zone 3 | BP: 68/45 mmHg, HR: 49/min |

| 115 | Transfer to the operating room | |

| 132 | General anesthesia started | BP: 100/55 mmHg, HR: 60/min |

| 166 | Open surgery started | BP: 85/49 mmHg, HR: 50/min |

| 236 | Aortic clamp and REBOA deflation | BP: 100/60 mmHg, HR: 50/min |

| 403 | Open surgery completed |

- Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; ER, emergency room; pRBC, packed red blood cells; rAAA, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm; REBOA, resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

A detailed interpretation of the CT scan revealed that the rAAA extended inferiorly to the renal artery. Although direct repositioning from Zone 1 to 3 is simpler and easier, the length of the currently available REBOA catheter is not long enough to reach Zone 3 from the brachial artery. Consequently, we repositioned the balloon to Zone 3 using the right femoral artery approach. A guide wire was advanced beyond the ruptured aneurysm (Figure 2B). The REBOA catheter was then retracted from the left brachial artery and repositioned for the partial occlusion of Zone 3 using an over-the-wire technique from the femoral artery. Contrast-enhanced imaging confirmed the proper positioning of the inflated balloon at the aneurysm neck (Figure 2C,D). Through partial REBOA, the SBP was maintained at 70–80 mmHg, with palpable peripheral pulses. Given the anatomy of the aneurysm, graft replacement (GR) was performed.

Laparotomy was initiated 81 min after aortic occlusion because of the operating room's availability and the patient's hemodynamics. The aortic aneurysm was approached while managing the adhesions. The bowel showed acceptable coloration and peristalsis. The REBOA provided hemodynamic support until proximal aortic clamping occurred 70 min after surgery, after which it was removed. The total complete occlusion time was 9 min, while partial occlusion lasted 141 min. GR (I-grafting) was performed, and the abdomen was closed. The total volume of blood loss was 1700 mL, requiring the transfusion of 16 units of packed red blood cells, 8 units of fresh frozen plasma, and 20 units of platelets.

The patient was extubated on the seventh postoperative day. The intravesical pressure remained at approximately 10 mmHg (normal range: 5–7 mmHg) without signs of abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). The patient was eventually discharged on postoperative day 28.

DISCUSSION

We initially performed left brachial Zone 1 REBOA to stabilize the hemodynamics in the case of rAAA and subsequently switched to femoral Zone 3 REBOA after identifying the infrarenal aneurysm to ensure adequate organ perfusion. Blood transfusions and partial REBOA enabled prolonged management.

Raw is a life-threatening vascular emergency with high mortality rates attributed to hemorrhagic shock.1 Despite treatments, such as endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and GR, mortality remains high.1, 5 Prompt diagnosis and immediate treatment are crucial, with a recommended door-to-intervention time of <90 min.6 In our patient, it took 45 min from the time of hypotension to REBOA, and laparotomy was initiated 81 min after aortic occlusion because of the operating room's availability and the patient's hemodynamics. If access to fluoroscopy was difficult or it was anticipated that REBOA could not be safely performed in Zone 1, open chest aortic occlusion could be considered in cases of imminent cardiac arrest.

REBOA is employed for temporary hemorrhage control in subdiaphragmatic injuries and effectively maintains hemodynamics in cases of rAAAs.3, 7 The femoral artery approach is utilized in over 95% of REBOA procedures.3 In our patient, Zone 1 REBOA was initially performed via the left brachial artery as the primary approach to managing the rAAA. It was essential for providing hemodynamic support and proximal control owing to an impending cardiac arrest. Not only in the brachial approach, fluoroscopy guidance is more preferable both in brachial and femoral access in the case of AAA.

We performed a two-stage REBOA for infrarenal rAAA. Although direct repositioning from Zone 1 to 3 is simpler and easier, the length of the currently available REBOA catheter in our institution (RESCUE BALLOON®-ER, Tokai Medical Products, Inc., Aichi, Japan, 75 cm length) was not long enough to reach Zone 3 from the brachial artery. RESCUE BALLOON® (80 cm length) is preferable to reposition Zone 1 from Zone 3 via brachial access, which is simpler and less expensive but only achievable in small physique patients. The exchange to femoral access is universal regardless of the physique and safer to avoid further rupture. Because of the high migration risk, especially in the reverse taper aortic neck, transporting patients and circulatory change on anesthesia are also very high risks. Considering hemodynamics and maintenance of organ perfusion, we decided to change from Zone 1 to Zone 3 REBOA. Zone 3 REBOA is preferred to preserve organ perfusion as it does not interrupt the visceral artery flow. Considering further rupture of the abdominal aortic aneurysm, a guidewire was placed through the femoral artery to minimize hemodynamic compromise before removing the REBOA catheter from the brachial artery.

The total time for a complete REBOA was 9 min, while that for a partial REBOA was 141 min. Although earlier transport to the operating room is ideal, it took approximately 2 h from the drop in blood pressure to the start of surgery in our patient because of the resuscitation and preparation. Controlling infrarenal rAAA with Zone 3 REBOA effectively maintained hemodynamics combined with partial REBOA and blood transfusions. Previous studies have indicated that bowel ischemia occurs within 40 min after conducting Zone 1 REBOA.2 Although early definitive hemostasis within 15 min is recommended,8 immediate surgery is not always feasible. Prolonged occlusion is possible by minimizing Zone 1 occlusion and combining Zone 3 or partial REBOA with transfusion to mitigate organ ischemia.9, 10 The patient did not develop any REBOA-related complications such as bowel ischemia or ACS. Early organ perfusion management is crucial for reducing post-REBOA ischemia–reperfusion injury.

CONCLUSION

We successfully managed a patient with infrarenal rAAA using REBOA to prevent cardiac arrest and ischemic complications. Brachial Zone 1 REBOA was initially employed for rAAA resuscitation. Conversion to Zone 3 REBOA, partial REBOA, and sufficient blood transfusion mitigated the REBOA-related complications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Mitsuo Ohnishi is the Editorial Board member of the Acute Medicine and Surgery Journal and a co-author of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol: N/A.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.