Preparedness of Australasian emergency departments for point-of-care ultrasound in the COVID-19 pandemic

[Correction added on 25 October 2021 after first online publication: The Figure 1 in the article was removed]

Abstract

Introduction

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been brought to the limelight again, with a surge in lung ultrasound in suspected COVID-19 patients. This is due to POCUS superiority over chest X-ray, equivalent efficacy to computerised tomography chest for COVID-19 diagnosis and potential minimisation of cross-infection. However, inadequate disinfection practices could make ultrasound machines a vector for disease transmission. This study, conducted during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, surveyed the preparedness of Australasian Clinicians for responsible POCUS practice within the Emergency Department (ED).

Methods

An anonymous online survey conducted from 20th April to 3rd June 2020 among emergency clinicians providing POCUS within Australasian EDs investigated preparedness to provide effective POCUS while minimising cross-infection.

Results

The survey received 171 responses and 116 being eligible for analysis. Most respondents (n = 96, 98%) had a separate ‘hot zone’ with a dedicated US device (n = 75, 77%), but lacked COVID-19-specific standard-operating procedures (n = 51, 52%) or a designated safety and compliance officer (n = 36, 37%). Most clinicians (n = 86, 88%) were willing to perform ultrasound in highly infectious patients, despite poor formal training (n = 66, 67%) or COVID-19-specific lung protocols (n = 59, 60%). Most (n = 92, 93%) had access to appropriate low-level disinfectant wipes but varied significantly in disinfection practice due to a lack of timely, formal or unified guidelines.

Conclusion

Australasian EDs significantly lacked investment in education, training and protocols to conduct safe POCUS in the COVID-19 pandemic. A framework with evidence-based, logistically feasible protocols supporting safe emergency POCUS is required to deal with similar future infectious outbreaks.

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation on 11 March 2020. By 29 April 2020, the virus had infected 3,024,059 people across 213 countries, with 7,891 cases in Australia and New Zealand.1 It has rapidly changed how Emergency Departments (EDs) provide quality care and maintain healthcare worker safety while limiting cross-infection. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in EDs is a rapidly growing subspecialty2 and is again in the limelight during this pandemic due to the efficacy of lung POCUS in the diagnosis, assessment of severity and monitoring of disease progression in COVID-19 patients.3-5 Lung POCUS has an excellent correlation to computerised tomography (CT) chest5 and is superior to chest X-ray (CXR).6 Its use reduces transfers to the radiology department and subsequent exposure to radiology staff, porters and other patients.7 However, ultrasound devices can be potential vectors for transmitting pathogens,8 as SARS-CoV-2 can persist on plastic for up to nine days at room temperature. Therefore, infection prevention and control (IPC) measures are essential9 in limiting potential transmission.

To date, multiple international position statements exist for the safe use of ultrasound,10-14 but at the time of this survey, apart from the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (WFUMB),15 and by AJUM, Basseal et al.,16 there were no emergency medicine fraternity guidelines for the safe use, or cleaning of POCUS equipment, specific to COVID-19. Anecdotally, ultrasound machines are easily contaminated in busy ED settings due to multiple factors, posing a question on safe POCUS practice in COVID-19 patients. We also anticipated fear and uncertainty among emergency clinicians performing POCUS on these highly infectious patients. This study surveys the preparedness for safe POCUS use in suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients in Australasian EDs and the current practices, policies and mindset of emergency clinicians using POCUS during the early phase of this pandemic.

Materials and methods

This is a cross-sectional ‘open’ survey of the preparedness and safe use of ultrasound within EDs across Australia and New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected from 20 April 2020 to 3 June 2020 through an online survey platform, Survey Monkey™. A short explanation regarding the study's purpose estimated time to complete the study, and investigators' details were provided to participants on the survey's initial page as a preamble. The working group designed survey questions – an expert in POCUS in ED (VM), an expert in microbiology and infection prevention and control (JB) and emergency medicine advanced trainees undergoing training in POCUS (DH, GK, DR, JM). The survey had 36 questions spread across five sections, including participant characteristics, ED preparation for POCUS in COVID-19, sonologist preparation for POCUS in COVID-19, disinfection practices and top three challenges with plausible solutions (Appendix 1—complete survey tool). The estimated time to completion was < 10 min. The options for answers were a mixture of free text and multiple choice, with some of the multiple-choice questions allowing several answers to be selected. Mandatory questions were highlighted, and all questions had a non-response (‘other’) option with free-text functionality. Participants were given the ‘back’ menu option to revise their responses at any time before final submission. To reduce the complexity and improve the completion rate, an adaptive questioning technique or skip technique has been used to reduce the number of questions based on the participant's response. After the initial demographics section, if the participant's ED has decided not to use POCUS in COVID-19 patients, they could skip the remaining sections to exit the survey.

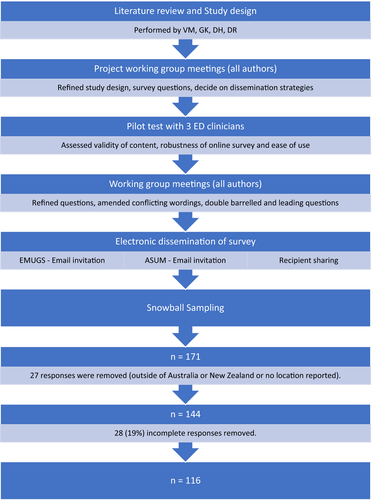

Considering the pandemic situation and the time criticalness to capture this valuable information, this survey was piloted with only three emergency clinicians to assess the content, technical robustness and ease of use. After refinements and amendments, all authors agreed on the final version of the survey questions before dissemination (Figure 1).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Adventist HealthCare Limited Human Research Ethics Sub-committee (approval reference HREC Project ID: 2020-009). Participation in the survey was voluntary. The completion of the survey inferred consent, and this was clearly stated in the preamble. Only de-identified data were collected.

Dissemination strategy and study sample

A survey link was sent via an email list generated by the Australasian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine (ASUM) and Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Groups (EMUGs) to target participants, who were the Clinical Leads in Ultrasound (CLUS) in ED, POCUS administrators and ED POCUS users (Emergency Physicians, Emergency medicine trainees, Sonographer educators in ED (SEED), Nurses, Nurse practitioners and Clinical assistants) in Australia and New Zealand. Recipients and survey respondents could forward the survey link to colleagues at their discretion, resulting in snowball sampling. Respondents from outside of Australasia were excluded from the study. No monetary or non-monetary incentive was offered to participants.

Statistical data analyses

Individual survey responses were analysed, and incomplete responses were removed. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographics and frequency of survey responses. Responses, where more than one answer may be selected, were analysed using descriptive statistics per question rather than per respondent. Free-text responses were reviewed and grouped into existing response categories or addressed separately within the results section. All statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software version 4.0.3.

RESULTS

The survey received 171 responses. Of these, 27 responses were removed as they were received from respondents outside of Australasia, or they gave no demographic information about their location of the practice. An additional 28 responses were removed due to incomplete answers. Data were analysed for the remaining 116 responses.

Participant characteristics

Of the 116 respondents, 103 (89%) were from Australia and 13 (11%) from New Zealand (Table 1). Responses from NSW (Australia) constitute 48% (56/116) of the overall respondents. Public hospital workers made up 93% (108/116), of which 81% (88/108) were from public metropolitan hospitals. Most of the respondents, 84% (98/116), were medical graduates, of which 77% (75/98) were Fellows of the Australasian College of Emergency Medicine (FACEM). Notably, 49% (57/116) of the total responses were from doctors who are the CLUS in ED. Most of the CLUS 54% (31/57) hold the certificate in clinician performed ultrasound (CCPU), and 19% (11/57) hold a Diploma in Diagnostic Ultrasound (DDU) or Masters in Ultrasound. Interestingly, 12% (7/57) of the CLUS reported that they have no formal ultrasound qualification.

| Respondent's location | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Capital Territory | 1 | 1 | ||

| New South Wales | 56 | 48 | ||

| Northern Territory | 2 | 2 | ||

| Queensland | 8 | 7 | ||

| South Australia | 15 | 13 | ||

| Tasmania | 1 | 1 | ||

| Victoria | 12 | 10 | ||

| Western Australia | 8 | 7 | ||

| New Zealand | 13 | 11 | ||

| Total | 116 | 100 | ||

| Hospital Setting | n | % | ||

| Private Metropolitan | 4 | 3 | ||

| Private Regional | 4 | 3 | ||

| Public Metropolitan | 88 | 76 | ||

| Public Regional | 18 | 16 | ||

| Public Rural | 2 | 2 | ||

| Total | 116 | 1 | ||

| Referral centre | n | % | ||

| Yes | 63 | 54 | ||

| No | 50 | 43 | ||

| Unsure | 3 | 3 | ||

| Total | 116 | 100 | ||

| Job Title | Qualification | Section total | n | % |

| CLUS | ACEM pathway - Inhouse Credentialled | 57 | 2 | 4 |

| CCPU | 31 | 54 | ||

| DDU | 9 | 16 | ||

| Masters in Ultrasound | 2 | 4 | ||

| No Formal Qualification | 7 | 12 | ||

| Other | 6 | 11 | ||

| Consultant/FACEM | CCPU | 18 | 3 | 17 |

| No Formal Qualification | 14 | 78 | ||

| Other | 1 | 6 | ||

| Nurse/NP/CA | CAHPU | 10 | 5 | 50 |

| No Formal Qualification | 5 | 50 | ||

| Registrar/CMO/JMO | CCPU | 23 | 7 | 30 |

| No Formal Qualification | 16 | 70 | ||

| Sonographer/SEED | DMU | 7 | 3 | 43 |

| Masters in Ultrasound | 3 | 43 | ||

| Other | 1 | 14 | ||

| Other | Other | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Total | 116 | |||

- CLUS, Clinical Lead in Ultrasound; FACEM, Fellow of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine; NP, Nurse Practitioner; CA, Clinical Assistant; SEED, Sonographer Educator in Emergency Department; ACEM, Australasian College for Emergency Medicine; DDU, Diploma in Diagnostic Ultrasound; DMU, Diploma in Medical Ultrasound; CCPU, Certificate in Clinician Performed Ultrasound; CAHPU, Certificate in Allied Health Performed Ultrasound.

Exit strategy

Of the 116 respondents, 18 (16%) answered that their ED would not be performing bedside ultrasound on COVID-19 patients, hence exited the survey bypassing the other sections. Data of the remaining 98 respondents are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Emergency Department Preparation for POCUS in COVID-19 | ||

| Does your ED have a designated COVID-19 management section, ‘hot zone or red zone’? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 96 | 96 |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Unsure | 1 | 1 |

| Does your ED have a formal SOP (standard-operating procedure) for ultrasound in suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 51 | 52 |

| No | 31 | 32 |

| Unsure | 16 | 16 |

| Does your ED have an allocated person to monitor safety and compliance in using ultrasound in COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 36 | 37 |

| No | 43 | 44 |

| Unsure | 19 | 19 |

| Is there a designated ultrasound machine(s) for COVID-19 patients in your department? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 75 | 77 |

| No | 21 | 21 |

| Unsure | 2 | 2 |

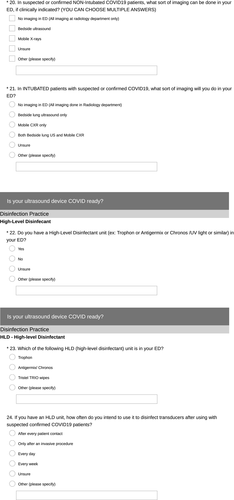

| In suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients, who are NOT INTUBATED, what sort of imaging can be done in your ED, if clinically indicated? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| No imaging in ED (imaging at radiology department only) | 1 | 1 |

| Bedside Ultrasound | 85 | 87 |

| Mobile X-rays | 91 | 93 |

| CT scan | 4 | 4 |

| Unsure | 1 | 1 |

| In INTUBATED patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, what sort of imaging will you do in your ED? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| No imaging in ED (imaging at radiology department only) | 1 | 1 |

| Bedside lung ultrasound only | 6 | 6 |

| Mobile CXR only | 11 | 11 |

| Both Bedside lung US and Mobile CXR | 72 | 73 |

| Unsure | 3 | 3 |

| Sonologist (Emergency Clinician) Preparation for POCUS in COVID-19 | ||

| If clinically required, will YOU perform ultrasound in COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 86 | 88 |

| No | 2 | 2 |

| Maybe | 10 | 10 |

| Have you received any formal teaching or training on safely performing ultrasound in COVID-19? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 26 | 27 |

| No | 66 | 67 |

| Self-taught | 5 | 5 |

| Unsure | 1 | 1 |

| What type of ultrasound device do you intend to use in suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Handheld device only (e.g. Butterfly, Lumify, Sonoviz) | 5 | 37 |

| Larger portable US machine only (e.g. Philips Sparq, Sonosite X-Porte, GE Venue, Mindray TE7) | 84 | 44 |

| Both handheld and large portable machine | 9 | 19 |

| What sort of US examinations do you intend to perform in COVID-19 patients? (can choose multiple options) | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Lung ultrasound | 49 | 50 |

| Cardiac ultrasound | 49 | 50 |

| US-guided IV access (PVC or CVC insertion) | 52 | 53 |

| Foetal well-being assessment | 16 | 16 |

| EFAST/AAA/DVT | 39 | 40 |

| All relevant POCUS and advanced scans (no limitation) | 57 | 58 |

| Do you or intend to assess the severity of COVID-19 disease using lung ultrasound? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 43 | 44 |

| No | 44 | 45 |

| Unsure | 11 | 11 |

| Do you use a COVID-19-specific lung scanning protocol? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 35 | 36 |

| No | 59 | 60 |

| Unsure | 4 | 4 |

- ED, Emergency Department; CXR, Chest X-ray; EFAST, Extended Focussed Assessment with Sonography in Trauma; AAA, Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm; DVT, Deep Venous Thrombosis; PVC, Peripheral Venous Catheter; CVC, Central Venous Catheter.

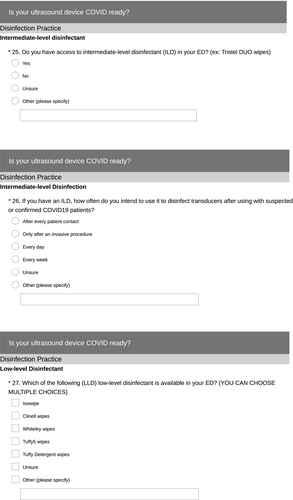

| Cleaning and disinfection practice | ||

| Do you have a High-Level Disinfectant unit (e.g. Trophon or Antigermix or Chronos/UV light or similar) in your ED? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 30 | 31 |

| No | 49 | 50 |

| Shared with another department (e.g. Radiology) | 5 | 5 |

| Unsure | 14 | 14 |

| Which of the following HLD (high-level disinfectant) units are in your ED? | ||

| Response (Total n = 30) | n | % |

| Trophon | 20 | 66 |

| Antigermix/Chronos | 5 | 17 |

| Tristel Trio Wipes | 5 | 17 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| If you have access to a HLD unit, how often do you intend to use it to disinfect transducers, after scanning a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient? | ||

| Response (Total n = 35) | n | % |

| After every patient contact | 20 | 57 |

| Only after an invasive procedure | 5 | 14 |

| Every day | 2 | 6 |

| Every week | 1 | 3 |

| Unsure | 4 | 11 |

| Other (see responses below) | 3 | 9 |

| ‘Only if visibly contaminated’, n = 1 | ||

| ‘Only for inadvertent exposure of probe to body fluids’, n = 1 | ||

| ‘Only after exposure to aerosolising procedure’, n = 1 | ||

| Do you have access to intermediate-level disinfectant (ILD) in your ED? (ex: Tristel DUO wipes) | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 44 | 45 |

| No | 38 | 39 |

| Unsure | 16 | 16 |

| If you have an ILD, how often do you intend to use it to disinfect transducers after using it with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 44) | n | % |

| After every patient contact | 40 | 67 |

| Only after an invasive procedure | 2 | 3 |

| Every day | 1 | 2 |

| Every week | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 2 |

| ‘only HLD for confirmed COVID-19 patients’, n = 1 | ||

| Which of the following (LLD) low-level disinfectant is available in your ED? (You can choose multiple choices) | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Clinell Wipe | 69 | 70 |

| Isowipe | 39 | 40 |

| Tuffy5 Wipe | 24 | 24 |

| Tuffy Detergent Wipe | 24 | 24 |

| Whiteley Wipes | 3 | 3 |

| Unsure | 7 | 7 |

| Other (see responses below) | 4 | 4 |

| Chem 7, n = 1 | ||

| Oxyvir, n = 1 | ||

| Sani cloth, n = 1 | ||

| V-Wipes, n = 1 | ||

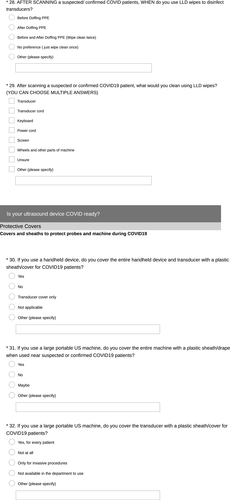

| AFTER SCANNING a suspected/confirmed COVID-19 patient, when do you use LLD wipes to disinfect transducers? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Before and After Doffing PPE (Wipe clean twice) | 58 | 59 |

| After Doffing PPE | 19 | 19 |

| Before Doffing PPE | 10 | 10 |

| No preference (just wipe clean once) | 8 | 8 |

| Unsure | 3 | 3 |

| After scanning a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient, what would you clean using LLD wipes? (You can choose multiple answers) | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Transducer | 95 | 96 |

| Transducer Cord | 90 | 92 |

| Keyboard | 83 | 85 |

| Power cord | 65 | 66 |

| Screen | 84 | 86 |

| Wheels and other parts of the machine | 46 | 47 |

| Unsure | 3 | 3 |

| If you use a handheld ultrasound device, will you cover the entire device and transducer with a plastic sheath/cover for COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 13 | 13 |

| No | 12 | 12 |

| Transducer cover only | 4 | 4 |

| Not applicable | 67 | 68 |

| Unsure | 1 | 1 |

| If you use a large portable US machine, will you cover the entire machine with a plastic sheath/drape when used near suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes | 22 | 22 |

| No | 60 | 61 |

| May be | 12 | 12 |

| Unsure | 4 | 4 |

| Other – During Aerosolising procedure only | 2 | 2 |

| If you use a large portable US machine, will you cover the transducer with a plastic sheath/cover for COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Yes, for every patient | 47 | 48 |

| Only for invasive procedures | 34 | 35 |

| Not at all | 9 | 9 |

| Not available in ED to use | 4 | 4 |

| Unsure | 4 | 4 |

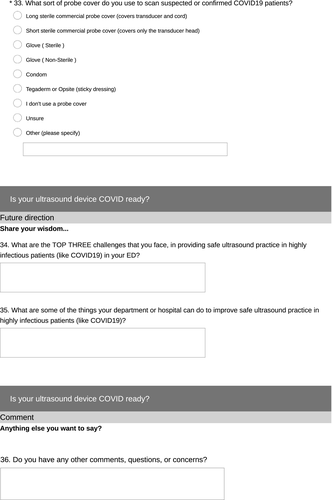

| What sort of probe cover do you intend to use on suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients? | ||

| Response (Total n = 98) | n | % |

| Long sterile commercial probe cover (covers transducer and cord) | 65 | 66 |

| Short sterile commercial probe cover (covers only the transducer head) | 8 | 8 |

| Glove (Sterile) | 0 | 0 |

| Glove (Non-Sterile) | 2 | 2 |

| Condom | 1 | 1 |

| Sticky Dressing (e.g. Tegaderm™ or Opsite™) | 0 | 0 |

| I don't use a probe cover | 14 | 14 |

| Unsure | 3 | 3 |

| Other (see responses below) | 5 | 5 |

| Freezer Bags, n = 2 | ||

| Long cover for confirmed or high risk, short cover for low-risk patients, n = 1 | ||

| Long sterile cover only for invasive procedures, n = 1 | ||

| Not needed as no guidelines yet, n = 1 | ||

- ED, Emergency Department; HLD, High level disinfectant; ILD, Intermediate level disinfectant; LLD, Low level disinfectant.

ED preparation for POCUS in COVID-19

As per table 2, 98% (96/98) of participant's EDs had a dedicated ‘Hot Zone’ area with a dedicated ultrasound machine in 77% (75/98). Only 52% (51/98) had a standard-operating procedure (SOP) in place to assess and manage suspected COVID-19 patients, and only 37% (36/98) reported having a designated person to monitor safety and compliance of ultrasound use in COVID-19 patients. Eighty-seven per cent (85/98) of respondents and 79% (79/98) of respondents intended to perform bedside lung ultrasound in non-intubated and intubated COVID-19 patients, respectively.

Sonologist (clinicians performing ultrasound) preparation for POCUS in COVID-19

As per Table 2, most of the respondents, 88% (86/98), were prepared to perform an ultrasound on COVID-19-positive patients. However, 67% (66/98) of respondents reported no formal teaching or training on safely performing ultrasound on these infectious patients, and 60% (59/98) reported no COVID-19-specific lung scanning protocol. In this survey, 58% were willing to perform all relevant POCUS and advanced ultrasound scans, including lung, cardiac, early pregnancy, musculoskeletal, abdominal, ocular and core POCUS modalities EFAST, AAA, DVT and vascular access.

Disinfection practice and policies for POCUS in COVID-19

Table 3 summarises the intended cleaning and disinfection practice of ultrasound devices when used on COVID-19 patients. Only 31% (30/98) of respondents reported having access to HLD (high-level disinfection) in ED, and among them, 67% (20/30) have a Trophon HLD unit. A total of 5% (5/98) share the HLD unit with another department. Among those who have access to HLD (35/98), 57% (20/35) intend to use it after every contact with COVID-19 patients, and 14% (5/35) prefer to use HLD only after an invasive procedure.

A total of 45% (44/98) of respondents had access to ILD (intermediate-level disinfection) wipes, and 67% (40/44) intend to use them after every COVID-19 patient encounter. Ninety-three per cent of respondents (92/98) had access to LLD (low-level disinfectant) wipes in their ED, with 70% (69/98) reported having Clinell™ LLD wipes. Fifty-nine per cent (58/98) reported cleaning the transducers with LLD wipes before and after doffing personal protective equipment (PPE), and only 3% (3/98) were unsure on which parts of the ultrasound machine to be cleaned.

For those with handheld devices (30/98), 43% (13/30) of respondents reported covering the entire device and transducer with a plastic sheath or cover, 13% (4/30) cover the transducer only. Of those using the large portable ultrasound machines, 22% (22/98) reported covering the entire machine with plastic drape, and 2% (2/98) would drape it only during aerosolising procedure. Forty-eight per cent (47/98) of respondents intend to use a transducer cover for every COVID-19 patient, and 35% (34/98) prefer to use it only during an invasive procedure. 9% (9/98) reported that they would not use transducer covers and 4% (4/98) had no access to transducer covers in their ED. Of those who use transducer covers, 66% (65/98) reported using long sterile commercial probe covers.

Qualitative responses – Challenges and solutions

Optional free-text comments were collected at the end of the survey on the top three challenges that were faced and three plausible solutions (Table 4).

| Challenges for POCUS in COVID-19 |

|---|

|

Emergency Department (ED) preparation

Sonologist (Emergency Clinician) preparation

Cleaning and disinfection

|

| Suggested solutions |

|

|

- PPE, Personal protective equipment; HLD, High level disinfectant.

Discussion

‘Preparing for the unknown’ is intriguing but scary, as there is an element of uncertainty and fear of failure. But by failing to prepare, we are preparing to fail. Advancement in microbiology and infectious diseases, and through lessons learned from past coronavirus outbreaks, including Middle East Respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS),17, 18 health response should have provided a head start in the preparation to combat this COVID-19 pandemic.

Emergency departments are at the forefront of health care and are pregnable to sudden threats like the COVID-19 pandemic. With the increased use of POCUS in current EDs, agreed guidelines and policies should be in place for safe POCUS practice in infectious outbreaks. In the earlier stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Australasian ED clinicians were preparing for a safe POCUS practice in ED, there was no gold-standard reference or succinct formal guidance from governing bodies. Individual institutions' preparation was hugely guided by regional infection control units, with inherent variation to suit their needs. Attempting to capture all those variations via this survey revealed interesting findings.

The survey received responses from Australia and New Zealand, but as most of the responses were from NSW (Australia), the results may not accurately represent widespread Australasian practices. As almost half of the responses are from CLUS in ED, who have in-depth knowledge about the status of POCUS in their ED, these data hold significant value. The general acceptance of a ‘Hot or Red Zone’ model to separate potential COVID-19 patients from others, and to have a dedicated ultrasound device in these hot zones, is in line with the recommendation by WUFMB.15 The need for a dedicated ultrasound machine in these hot zones is also echoed by respondents who did not have one (Table 4). Most of the respondents have access to large portable ultrasound machines and were not prepared to cover the entire machine with a plastic drape. This was likely due to a lack of suitably large drapes coupled with the difficulty in using the machine while draped. The preference was to cover the transducer and cord with a long sterile probe cover. A small, portable, even handheld ultrasound device in these hot zones would ease the logistical issues of cleaning and disinfection.12

SARS-CoV-2 is a small lipid-based enveloped virus that is efficiently inactivated by disinfectants such as 62-71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite, which are used in standard low-level disinfectants.16 Almost all the respondents had access to LLD wipes; however, practices on how and when these were used varied significantly (Table 3). This reflects the lack of clear departmental or governing body-issued policy on ultrasound device disinfection. Basseal et al. recommended cleaning the entire machine, but mainly the keyboard, screen and ultrasound probe cord, with LLD wipes.16 Most ultrasound manufacturers have waived rules about machine-specific disinfectants and support the use of any product effective against COVID-19.12 ILD wipes (e.g. Tristel Duo™) and HLD chemical-based systems (e.g. Trophon™ and high-intensity UV light, used in Chronos™/Antigermix™) are also effective in destroying SARS-CoV-2, but its availability in ED is scarce. A low proportion of respondents have access to HLD technology in ED, and use differed significantly after scanning COVID-19 patients. Some EDs share an HLD unit with other departments like radiology, making it logistically more challenging to safely and frequently disinfect probes. The survey's free-text option highlighted that respondents preferred to use small disposable gel packets when scanning COVID-19 patients, which was later widely recommended by most organisations.12, 15, 16

Despite low access to an SOP or guidelines for safe POCUS in COVID-19 (only half of the respondents had either) most of the respondents demonstrated a willingness to perform scans on these highly infectious patients. Consensus and recommendations are to minimise exposure during the examination by performing a truncated POCUS study16 and avoiding educational or practice scanning. The use of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 patients has been used to identify lung changes, assess severity and monitor progress,3, 19 but in this survey, the majority of the respondents were not intending nor aware of assessing the severity of lung involvement in COVID-19 with lung ultrasound and the majority did not have a COVID-19 specific lung scanning protocol.

The significant gaps identified by this survey include staff education and governance of POCUS in ED and lack of awareness of protocols and guidelines for safe scanning techniques and ED-specific effective cleaning and disinfection techniques. There was also a lack of resources such as handheld ultrasound devices, HLD units, purpose-built plastic drapes to cover entire ultrasound device and smaller disposable ultrasound gel packets.

To date, this is the most significant viral pandemic that EDs have encountered since POCUS has become a widely-used practice. There have been several guidelines for safe medical ultrasound practices during COVID-19 published since launching the survey, mainly in speciality areas like obstetrics and gynaecology, critical care and general ultrasound10, 11, 13, 16, 19; however, there is still a lack of official guidelines readily available specifically for emergency clinicians. As the world of medicine continually evolves and accommodates newer technologies and practices such as POCUS in EDs, it is essential to upskill infection prevention and control practice to combat infectious disease outbreaks like COVID-19.

Limitations

This study was conducted during the COVID-19 crisis amidst unprecedented limitations, hence the lack of robust survey tool validation. This is an open survey with de-identified participation and has no control over preventing multiple entries from a single institution or the same participant. Most of the responses were from the state of NSW, potentially reducing the ability to generalise the findings. Participation was voluntary, and this survey was conducted during the COVID-19 crisis period, which yielded a completion rate of only 84% and a smaller sample size limiting any statistical analysis.

Conclusion

POCUS is widely used by clinicians and is crucial for diagnosing and managing clinical conditions in EDs. Whilst lung ultrasound has proven to be valuable in the management of COVID-19, there is a significant lack of investment in adequate training, protocol development, and infrastructure to conduct safe POCUS in the ED. This survey has highlighted the importance of clear and timely guidance from governing bodies. A framework for supporting POCUS in EDs is required to ensure patient and staff safety, and the time is now to invest in preparedness for future infectious disease outbreaks.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge with gratitude the Emergency Care Department at Sydney Adventist Hospital for providing invaluable support in conducting this survey. Thanks to the Australasian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine (ASUM) and the Emergency Ultrasound Group (EMUGs) for their help in the dissemination of the survey. Thanks to Dr Mary Ibrahim for the support in manuscript proofreading.

Author contributions

Vijay Manivel: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (lead); Resources (equal); Software (equal); Supervision (lead); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (lead); Writing-review & editing (equal). David G Herbert: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (lead); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Software (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Gareth Ian Kitson: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Writing-original draft (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Dougal Buchanan Robertson: Conceptualization (equal); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Writing-original draft (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting). James Manion: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (supporting). Jocelyne Basseal: Conceptualization (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Resources (supporting); Supervision (supporting); Visualization (equal); Writing-original draft (supporting); Writing-review & editing (supporting).

Conflict of interest

No competing or conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding or financial support was received for this project.

Authorship declaration

Authors declare that the entire research work including manuscript writing is their original work and it is not been published or presented in any other scientific journals or meetings or conference. All authors agree with the content of the manuscript. All authors agree to AJUM’s authorship policy.