All together now: Assessing variation in maternal and nonmaternal handling of wild Colobus vellerosus infants

Abstract

Primatologists have a long-standing interest in the study of maternal care and nonmaternal handling (NH) of infants stemming from recognition that early social relationships can have enduring consequences. Though maternal care and NH often include expression of similar behaviors, they are regularly studied in isolation from each other with nonoverlapping terminology, thereby overlooking possible interplay between them and obfuscating potential developmental ramifications that ensue from trade-offs made between maternal (MH) and NH during infancy. To that end, identifying how MH and NH patterns interact and contribute to the total handling (TH) infants receive is a critical first step. We present durational handling data collected from 25 wild Colobus vellerosus infants from 2016 to 2017 and assess the relationships between TH, MH, and NH. Patterns of social affiliation are shaped in part by surrounding context, and therefore, we also assess whether NH and TH differ in their responsivity to various infant and social group characteristics. Ninety-four percent of observed handling was MH, while just 5.5% was NH. Young infants who received more MH (excluding nursing) also received more NH; there was no relationship between the two in older infants. Infants in larger groups participated in more handling of all types. Additionally, NH time was associated with infant sex and group stability. Non-nursing TH time was associated with group stability and infant cohort size. Though NH variation likely confers social-networking advantage, in this population NH is not a major contributor to TH and would not effectively replace reduced MH. The positive association between MH and NH during early infancy suggests that colobus mothers may play a mediating role in shaping infant socialization. This is a first step in elucidating how different forms of handling relate to one another in wild primates and in identifying the impact of handling on infant socialization.

Highlights

-

We quantified infant participation in handling interactions with mothers and nonmothers using durational data to assess the relationship of each handling type to the total amount of handling that infants receive in Colobus vellerosus.

-

The only relationship between maternal and nonmaternal handling times occurred during early infancy: infants who participated in the most maternal handling also had the highest nonmaternal handling times.

-

Total and nonmaternal handling time in C. vellerosus varied in response to separate social factors; overall, patterns of variation in nonmaternal handling were drowned out by the outsized influence of maternal handling time.

Abbreviations

-

- GLMM

-

- generalized linear mixed effects model

-

- MH

-

- maternal handling

-

- NH

-

- nonmaternal handling

-

- TH

-

- total handling

1 INTRODUCTION

Within primates, interest in infants (“natal attraction”) and interactions between nonmaternal group members and infants is widespread (Tecot & Baden, 2015). The term nonmaternal infant handling (alternatively referred to as “allo-,” “allomaternal,” or “alloparental care”) applies to social interactions between infants and non-peer, non-mother individuals that often involves physical touch such as holding, playing, carrying and grooming (see Dunayer & Berman, 2018). Access to infants by non-mother individuals (“handlers”) is typically determined by maternal tolerance (Maestripieri, 1994, 2018). Nonmaternal handling interactions are dyadic (between handler and infant), but their frequency is based on a three-party negotiation of handler, mother, and infant interests. Infant handling encompasses both affiliative and antagonistic (e.g., hitting, biting, kidnaping) behaviors, such that maternal tolerance of infant handling is dependent on a distinct risk-reward balance that varies with species and/or rank. For instance, in colobines, handling is predominantly affiliative in nature, so handler access is permitted soon after (McKenna, 1979) or, in some cases, during birth (Li et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2014). In comparison, aggressive infant handling tends to occur more frequently in baboons and macaques; in these species low-ranking mothers, whose infants are most susceptible to aggressive handling, are highly protective and regularly attempt to resist or postpone handler access until their infants are older and less vulnerable (Chism, 2000).

The diversity of forms nonmaternal handling takes is reflective of the breadth of social functions it serves for mothers, handlers, and infants; thus, functional hypotheses to explain nonmaternal handling are generally not mutually exclusive (Maestripieri, 1994). Historically, research exploring functional hypotheses has focused heavily on potential benefits to nonmaternal handlers (learning to mother hypothesis: Lancaster, 1971; reciprocity hypothesis: Hrdy, 1976) and mothers (increased foraging time: Hrdy, 1976; Nicolson, 1987; increased reproductive rates: Fairbanks, 1990; Ross & MacLarnon, 2000). Alternatively, others have investigated handling as a transactional relationship whereby infants serve as trade commodity for mothers and handlers in a biological marketplace (Gumert, 2007; Henzi & Barrett, 2002; Jiang et al., 2019; Sekizawa & Kutsukake, 2023; Tiddi et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2013). A commonality shared by these diverse approaches is that mothers bear full agency in determining an infant's nonmaternal handling relationships (which may be an oversimplification), and that the consequences of maternal care patterns on development are much weightier than those of nonmaternal handling. This second point is undeniable, and yet, its assumption means that numeric analyses of maternal-infant interaction time as they relate to nonmaternal handling have overwhelmingly ceded spotlight to categorical analyses of maternal style. Quantified analyses of maternal handling variation in nonhuman primates are robust (e.g., Maestripieri et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2012; Stanton et al., 2015), but they typically adopt alternate language (such as “maternal care” or “investment”); this difference prevents comparison with nonmaternal handling and is representative of a broader phenomenon in which investigations of infant interactions with mothers and nonmothers operate as isolated streams of inquiry. Stemming from this, we still lack fine-tuned comparisons quantifying the differences in scale between maternal and nonmaternal effects on infant development.

Relatively few studies emphasize potential benefits to infants or discuss infants as active participants in and solicitors of infant handling behaviors (but see: Bădescu et al., 2015; Bales et al., 2000; Dunayer & Berman, 2017; Förster & Cords, 2005; Ross & Regan, 2000). Infant-focused research suggests that one unique benefit to higher participation in nonmaternal handling interactions is infants’ increased connectedness within their social group, which could potentially contribute to a lifelong advantage for the non-dispersing sex (Dunayer & Berman, 2017; Förster & Cords, 2005) or prepare infants for ingestion of solid foods by transferring beneficial gut microbiota (Wikberg et al., 2020). The predominant reason for the relative paucity of infant-focused handling research (as opposed to research focused on mothers and handlers) is likely a methodological barrier: this type of research requires collection of detailed, continuous focal data on infants, who are notoriously fast-moving, easily visually obscured by foliage or other individuals’ bodies, and often require modified ethograms and data collection protocols. Further, since many long-term field sites focus data collection on adults, this requires additional time and resources, and may not always be feasible. Yet, where researchers can do so, reframing infants as actors in handling interactions can be a small change with a big impact; it enables direct comparisons of mother and nonmaternal handler contributions to infant care and creates opportunities for novel, nuanced understanding of both maternal and nonmaternal care dynamics.

Because handling research has historically focused on handling by mothers and nonmothers as isolated phenomena, one major knowledge gap is to determine whether nonmaternal handling interactions add to or replace the care infants receive from their mothers. When unattended by mothers, infants may spend their time with nonmaternal handlers (in essence “replacing” maternal care). In this scenario, any lost participation in one form of handling is offset by an increase in the other, resulting in all infants receiving similar amounts of total handling time. This is largely the case for how infant care generally operates in human societies; human infants spend relatively little time unattended by caregivers, so reductions to direct maternal care are met with parallel increases in direct nonmaternal care (Kramer & Veile, 2018). With respect to nonhuman primates, it is reasonable to assume the same pattern exists for very young infants with limited mobility (Fairbanks, 1993) or species that practice infant-parking (Tecot et al., 2013), but it likely does not hold for older, mobile infants, and may lead to underestimation of total handling variation for a large portion of the infancy period. Even if maternal and nonmaternal handling do cumulatively offset one another relative to total handling, this still provides crucial context that is largely missing from our understanding of both maternal and nonmaternal handling variation. For example, mothers and nonmaternal handlers vary in the extent to which they (as social partners) help infants hone specific skillsets needed for adult competency (Lonsdorf & Ross, 2012). If infants do trade-off participating in one handling type for the other, any variation in the balance between them could bear developmental consequences.

Alternatively, it is also possible that nonmaternal handling adds to maternal care, so that some infants receive more total handling time than their peers. In this scenario, it is difficult to untangle whether social or developmental consequences of infants’ increased nonmaternal handling participation have a unique association with nonmaternal handling variation, rather than an association with imbalances in total handling time. This conundrum can only be addressed by analyzing variation in maternal and nonmaternal handling patterns side-by-side using an infant perspective. Reframing handling research in this way can also aid in elucidating other elements of variation among infants during a key developmental window. For example, chimpanzee infants at Ngogo make trade-offs between participation in nonmaternal handling interactions and time spent nursing with mothers, such that infants who are handled more by nonmothers ingest a greater proportion of non-milk food items for their age and develop more quickly (Bădescu, Watts, et al., 2016).

Regardless of whether infants interact with mothers or nonmothers, handling is an inherently social activity, and as with other aspects of sociality, surrounding context shapes participation patterns (Thompson, 2019). At its most basic, time and energy are finite resources for handlers and infants; individuals may compromise social investment as demands on feeding, travel, or rest increase (van Schaik et al., 1983). Similarly, changes in the availability of potential social partners, both within and outside one's age class (Pereira & Leigh, 2003), or threats to infant safety, including the presence of unfamiliar or infanticidal males (Scott et al., 2019, 2023), may alter how and with whom social time is apportioned. It is not always clear how these competing pressures play out for infants and handlers. For instance, both socialization needs (Amici et al., 2019; Lonsdorf et al., 2014) and infanticide risk (Sicotte & Teichroeb, 2008) can be sex-biased, but these differences may not necessarily warrant substantially different levels of handling participation for males and females (Lonsdorf, 2017). Further, in nonhuman primates, handling and grooming networks are often kin-biased (Chapais & Berman, 2004). Thus, when maternal siblings are present in group, infants may benefit from an increased availability of potential preferred handlers, while also experiencing greater competition for maternal social bandwidth (Lee, 1987). Group size presents a similar trade-off: infants residing in large groups may benefit from access to additional potential nonmaternal handlers, but larger groups of black-and-white colobus monkeys experience higher intragroup scramble competition and are more susceptible to male takeover and infanticide (Saj & Sicotte, 2007; Schülke & Ostner, 2012; Teichroeb et al., 2012). Additionally, larger groups often have larger infant cohorts; infants in these groups may trade-off peer social networking against handling participation, as is the case in blue monkeys (Förster & Cords, 2005). Provisioned rhesus macaques, for example, increase mother-infant contact time in larger groups, but this trend reverses seasonally, highlighting the flexibility with which handling responds to competing environmental pressures (Liu et al., 2018). It is widely accepted that, in primates, socialization and environmental context during infancy have extensive consequences for long-term behavioral expression (Lonsdorf & Ross, 2012). Yet, understanding how competing environmental pressures shape participation in early social networking through handling (overall and by source) is lagging, partially because it requires integrated maternal and nonmaternal handling data.

Colobus vellerosus (black-and-white or ursine colobus) is an ideal model system for investigating handling variation. Black-and-white colobus monkeys are arboreal, folivorous, and endemic to western Africa (Saj & Sicotte, 2007). Group structure is highly plastic in this species; for instance, groups range in size from 9 to 38 individuals and group structure vacillates between uni- and multi-male over time (Saj et al., 2005; Teichroeb et al., 2012; Wong & Sicotte, 2006). Male infanticidal attacks have been observed, particularly following the immigration of one or more new males into the social group (Saj & Sicotte, 2005; Sicotte & Macintosh, 2004; Teichroeb et al., 2011). Female black-and-white colobus disperse facultatively, with approximately half of females dispersing from natal groups (Teichroeb et al., 2009; Wikberg et al., 2012). Black-and-white colobus monkeys can broadly be considered resident egalitarian, and relationships between adult females are typically indifferent or relaxed with relatively low rates of aggression (Sterck et al., 1997; Wikberg et al., 2013; Wikberg et al., 2014). Infants are nutritionally dependent on mothers for over a year, although there is considerable variation in weaned dates (mean weaned age = 409 days, range = 275–640 days; Crotty, 2016). The average interbirth interval is 18.5 months (range = 8–21 months), and mothers are known to “stack investment” in offspring (conceiving/gestating while lactating) during favorable social conditions (Vayro et al., 2016, 2021). As with other colobines, nonmaternal handling is relatively frequent and predominantly affiliative (Brent et al., 2008). Nulliparous females and maternal kin are the most regular handlers, though individuals of all age and sex classes handle infants and female hierarchy positions do not affect handling rates (Bădescu et al., 2015).

The overarching goal of our study is to develop a more comprehensive understanding of how much infant handling variation exists within a population when nonmaternal and maternal handling durations are considered in tandem. More specifically, we aim to: (1) quantify the time colobus infants spend engaging in handling behaviors with mothers and nonmothers; (2) assess whether either maternal or nonmaternal handling are associated with the total volume of handling infants receive; (3) determine whether any connection exists between maternal and nonmaternal handling participation, such as whether nonmaternal handling replaces, or adds to, the handling infants receive from mothers; (4) elucidate the extent to which an infant's environment shapes participation in handling by investigating whether key infant- or group-specific characteristics are associated with nonmaternal and total handling variation. Through this layered approach, we hope to understand whether maternal and nonmaternal handling respond in parallel to social environment characteristics and, if not, elucidate how variation specific to one handling source impacts the total handling infants receive. Here we refer to “maternal handling” (MH) as infant handling interactions between infants and their mothers, while “nonmaternal handling” (NH) refers to handling interactions between infants and non-infant, non-mother individuals, including potential or known fathers. “Total handling” (TH) refers to the combined handling infants receive from all sources, including mothers.

Given that infants spend more time with mothers than any other social partner, we predict a positive association between the amount of MH and TH infants receive; we do not expect an association between NH and TH time (Aim #2). Nursing is functionally unique from other handling behaviors because it doubles as both feeding and socializing for infants. Therefore, in examining the relationship between MH and NH participation (Aim #3), we break down MH into “non-nursing MH” (i.e., all handling behaviors except nursing) and “nursing.” We predict that nursing and non-nursing MH patterns will differ in their relationship to NH, and that any relationships will be age-dependent, with weaker effects in older, more independent infants. With respect to Aim #4, we expect that infants, mothers, and nonmothers will modify handling participation in response to a variety of individual (sex) or group-level characteristics (size of group or infant cohort, group social stability, presence of maternal siblings). In previous analysis of nonmaternal handling patterns in black-and-white colobus monkeys, male infants engaged in handling bouts more frequently than female infants, and the authors hypothesized that males infants’ elevated infanticide risk may play a role in driving this pattern (Bădescu et al., 2015). As such, we predict that NH will be positively associated with infant sex (male) as well as a greater availability of all potential or related nonmaternal handlers (large group size, co-residence of maternal siblings), but we predict that NH is negatively associated with the presence of a larger infant social cohort or group social instability. We expect TH patterns will be predominantly driven by MH participation. Therefore, we predict that TH will be positively associated with group social instability and infant sex (male), while being negatively associated with higher availability of nonmaternal handlers (group size) and infant social partners (cohort size), and more competition with siblings for maternal social time (co-residence of maternal siblings).

2 METHODS

2.1 Ethical note

This study was approved by the University of Calgary's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All methods complied with the American Society of Primatologists’ Ethical Principles for the Treatment of Nonhuman Primates.

2.2 Study population

We collected data on a wild population of Colobus vellerosus residing in Boabeng-Fiema Monkey Sanctuary (BFMS) in central Ghana (7°43′ N and 1°42′W). BFMS is a small (1.9 km2), dry semi-deciduous forest fragment. The forest itself is protected as a conservation area while the surrounding area is a patchwork of small farm plots, villages, and additional forest fragments. BFMS has two main seasons annually—dry and wet—that span November-February and March-October, respectively (Saj et al., 2005). The colobus monkeys at BFMS have been under study by our research team since 2000, with year-round observation since 2014. All individuals in our four research groups can be identified and pedigrees are available for nearly all individuals (see Table S1 for group demography details).

2.3 Data collection

Our sample included all infants present in our four study groups during the 10 full months of data collection (June–November 2016, 2017). This included 27 infants born to 17 mothers (see Table S2). Due to limited available data, two infants were dropped from data analysis. For all infants, we conducted 10-min continuous focal samples to measure counts and exact durations of handling event and state behaviors, respectively (Altmann, 1974). Focal samples were dictated in real time by AGK and TR to trained assistants using the Animal Behavior Pro iPad application to ensure that the recording of duration data was accurate and precise. During focal sampling, we recorded all behaviors and their durations, as well as point samples every 2.5 min (which included identities of all individuals within 5 m and the distance to the infant's mother).

We collected focal and group scan samples 5 days a week between 6:30 and 15:00, to capture the diurnal period with the highest activity levels. On sampling days, we visited all visible groups and, whenever possible, all infants were sampled at least once. The order in which infants were sampled was determined by opportunity and time elapsed since last sample, with every effort made to balance sampling evenly between infants and time periods throughout the day (early morning, late morning, afternoon). We determined which members of the group were present each day based on scan samples of the group recorded at the beginning of each hour. Groups were considered socially “unstable” if one or more adult male membership changes (i.e., immigration or emigration events) had occurred within the last 14 days (see Supplementary Table 1). We recorded any observations of nursing (mouth-to-nipple contact) daily. When we failed to observe a focal subject nursing for 14 consecutive days, we determined that they had attained “weaned status” (Borries et al., 2014), thus the individual was no longer considered an infant and we ceased collecting focal data for that subject.

2.4 Coding handling

Our ethogram coded any interaction involving touch between an infant and non-infant individual as a handling behavior, irrespective of whether the behavior appeared affiliative or antagonistic in nature (see list of handling state behaviors in Table 1). As such, no distinction was made when handling interactions were “rough” in nature (such as when infants are clumsily carried by inexperienced nonmothers) or when infants vocalized during handling. During data collection, we did not observe any instances of antagonistic handling which were state behaviors, though we did observe several instances of antagonistic handling events (e.g., biting, grabbing, slapping). We recorded the duration of individual handling state behaviors, rather than bouts, and all handling durations were included. We avoided double-counting any co-occurring, non-mutually exclusive state behaviors (see Table 1) by identifying overlapping behaviors and excluding one behavior's duration from the infant's monthly handling sum. For example, infants can be held and groomed by the same handler at the same time. When infants were recorded as participating in more than one handling interaction simultaneously (for the duration of overlap) we counted only the duration of the behavior with the most active physical contact (e.g., grooming durations trumped holding durations when the two behaviors co-occurred).

| Behavior | Description |

|---|---|

| Carry | Infant is actively holding onto or gripping handler and in direct contact with the handler while handler is traveling (walking, traversing through canopy, climbing). Typically, but not always, infant is in contact with the handler's ventrum. |

| Groom | Infant is either actively giving or receiving grooming from handler. Infant and handler are in contact based on touch of fingers to hair, but other body parts may be in contact as well. May coincide with holding or nursing. |

| Hold | Infant is actively holding onto handler's ventrum and/or handler is actively holding onto the infant by wrapping arms or hands around the infant's body and keeping the infant in physical contact with their body. Handler is stationary. May coincide with nursing. |

| Nurse | The mouth of the infant is observed in contact with the nipple of the handler. Nursing may be either for nutritive or comfort suckling; both occur frequently in this species, and it is difficult to distinguish between the two visually. Allonursing is rare in C. vellerosus; attempts have been observed on a few occasions and are rarely successful (personal observation). |

| Play grapple | Infant and handler are actively grappling with one another, and contact is primarily maintained with hands, feet, and mouths of the individuals. Play grappling can be distinguished from agonistic interactions based on the presence of a unique “play face” on infants and/or handlers (mouth is open and relaxed) and lack of vocalizations. |

- Note. For each observation of these behaviors, we recorded handler identity and duration (in seconds).

Handling interactions were coded as “maternal” or “nonmaternal” based on handler identity; when observers were unable to identify the handler and the mother's location was simultaneously unknown, the handling interaction was coded as “unidentified.” An infant was coded as nursing only when nipple-to-mouth contact could be observed; when an infant's face was out of view, the infant was coded as “holding.” Nonmaternal nursing has been observed in this population on rare occasions (personal observation), and thus our ethogram allowed for both nonmaternal and maternal nursing. We did not observe any instances of nonmaternal nursing during this study, so all nursing behaviors were designated as maternal handling. Infants nurse to meet both nutritive and comfort needs, and primate studies using fecal stable isotope analysis reveal that observed nursing behaviors (mouth-to-nipple contact) occur long after mothers cease milk transfer (Bădescu et al., 2017; Reitsema, 2012; Reitsema et al., 2016). As observers we are unable to visually distinguish between nutritive and comfort nursing (Borries et al., 2014). We recognize that a key form of maternal handling is nursing and have chosen to include it in our datasets, even though no comparable nonmaternal version of this behavior was recorded in our population.

2.5 Data analysis

We summed the durations of all individual handling state behaviors and grouped by type of handling (NH, nursing, non-nursing MH, TH) and infant's age in months, resulting in a data set of 156 infant months. Months with less than 30 min of sampling time were dropped from analyses leaving 144 total infant months. For all analyses, we constructed generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMMs) using the lme4 and lmerTest packages in R (Bates et al., 2015; Kuznetsova et al., 2017; R Core Team, 2021). Data could not be transformed to a normal distribution, so we rounded handling sums to the nearest integer and ran our models with a negative binomial distribution. For all models, we included infant ID and age (in months) as random effects and sampling time (in minutes) as an offset; all numeric variables were scaled. We checked for multicollinearity and overdispersion for all models using the “vif” and “overdispersion_glmer” functions, respectively (Korner-Nievergelt et al., 2015). For each of our predictions, we compared a model that included our fixed effects against a corresponding null using a Chi-square analysis.

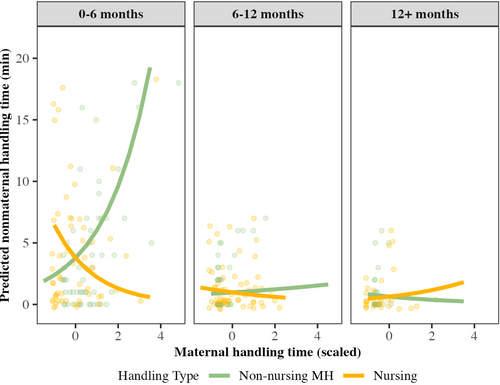

To test for associations between TH and the two contributing sources of handling (MH, NH; Aim #2), we created a GLMM model using total handling in minutes as a responding variable, then MH and NH minutes as fixed effects. We created an additional set of GLMMs to test for an association between the amount of MH and NH infants receive (Aim #3). In this species, young infants are reliant on close physical proximity with a caregiver for the first several months of life to meet their transportation and frequent nursing needs, while infants in their final months of nursing have very little reliance on mothers (Crotty, 2016). Thus, it is possible that the balance of MH and NH participation changes as infants age. Consequently, we evaluated the relationship between MH and NH by dividing our data set into three infant age categories (Cat 1: age 0–6 months, 57 infant-months; Cat 2: 6–12 months, 59 infant-months; Cat 3: 12+ months, 28 infant-months) and running separate GLMM models and corresponding null models for each infant age category. Fixed effects included: minutes spent nursing and minutes spent engaging in all other MH (i.e., nursing excluded).

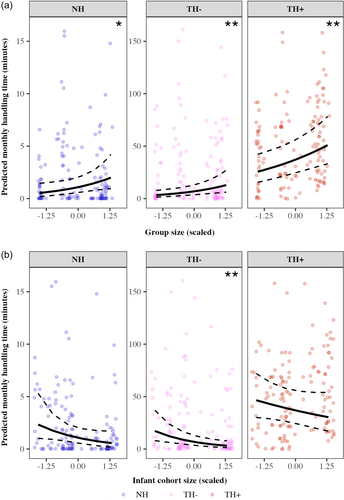

Lastly, to evaluate whether infant sex or any group-level characteristics predicted variation in TH and NH (Aim #4), we constructed a final set of GLMM models with the fixed effects: infant sex, presence of a maternal sibling in group (yes/no), group stability (stable/unstable), total group size, and infant cohort size. Although we recognize that a large portion of nursing—particularly in older infants—serves a nonnutritive purpose (Reitsema, 2012), we sought to evaluate TH both with and without nursing to untangle the extent to which TH patterns are driven by feeding patterns alone. Thus, we evaluated TH variation with two separate sets of models (one in which nursing time was included: “TH + ” and one in which it was excluded: “TH-”) to ascertain whether patterns of handling variation were altered by variation in time spent nursing with mothers.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Overall handling trends

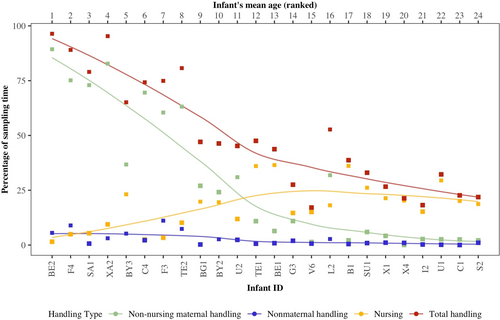

We collected 356.9 h of focal data from 25 infants (mean = 14.3 sampling hours/infant, range = 2.4–29.2 sampling hours/infant; see Supplementary Table 2). We stopped collecting data on eight individuals before the end of the study period: five infants attained “weaned” status and three infants disappeared. We observed 143.1 cumulative hours of handling for all study subjects (making up 40% of all sampling time); of this, 94% came from mothers, 5.5% came from nonmothers, and 0.5% was from unidentified sources (Supplementary Table 2).

The mean amount of TH received by infants was 5.7 h (range = 1.3–15.3 h/infant), which equated to 49.9% of sampling time (range = 17.1%–96.4%; Figure 1). We observed all infants receiving some amount of MH during the study (mean = 5.5 h/infant, range = 1.2–14.5 h/infant; mean = 47.3% of sampling time, range = 16.5%–92.2%; Figure 1). We did not observe all infants receiving NH (mean = 0.3 h/infant, range = 0.0–0.8 h/infant; mean = 2.5% of sampling time, range = 0%–11.1%; Figure 1); one infant (C1, aged 15–16 months during the study) was never observed receiving NH. Nearly all MH comprised of either nursing or holding infants, and this is also reflected in the breakdown of TH (Figure S1). NH and handling from unidentified sources most often consisted of holding, grooming, and play wrestling with infants (Figure S1).

3.2 Relationships between handling types

With respect to Aim #2, our results supported our prediction that TH was associated with MH and NH participation and our null model was rejected (χ2 = 12.204, df = 2, p = 0.002). TH time was associated with MH time; infants who engaged in more MH time also more had more TH time (β = 0.289, SE = 0.085, z = 3.410, p < 0.001). There was no association between TH and NH time (β = −0.111, SE = 0.072, z = −1.538, p = 0.124). Notably, there were no observed instances in which an individual with a below average participation in MH and an above average participation in NH also had an above average participation in TH, however there were several instances in which the reverse was true (high MH with low NH, yielding high TH; Figure 1).

We assessed the relationship between NH and MH (Aim #3) using model sets corresponding to each of our three age-specific subsets of data. For infants aged 0–6 months, we were able to reject our null model of ‘no association’ (χ2 = 6.837, df = 2, p = 0.033). NH was associated with both nursing and non-nursing MH time; infants received more NH when they spent less time nursing (β = −0.472, SE = 0.194, z = −2.433, p = 0.015; Figure 2a) and more time engaging in non-nursing MH (β = 0.436, SE = 0.178, z = 2.448, p = 0.014; Figure 2a). There was no association between NH and nursing or non-nursing MH for older infants; we were not able to reject our null models in the two older age groups (6-12 months: χ2 = 2.295, df = 2, p = 0.318; 12+ months: χ2 = 0.672, df = 2, p = 0.715; Figure 2).

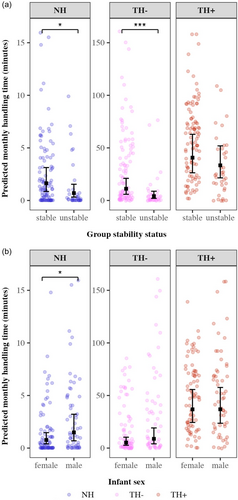

3.3 Predictors of total and nonmaternal handling

All three models (NH, TH without nursing “TH−,” TH with nursing: “TH+”) differed significantly from corresponding null models (Aim #4), suggesting that infants vary in the amount of time spent engaging all forms of handling in this population (NH: χ2 = 19.854, df = 6, p = 0.003; TH-: χ2 = 22.511, df = 6, p < 0.001; TH + : χ2 = 14.778, df = 6, p = 0.022).

NH was predicted by group stability, infant sex, and group size. Infants residing in groups experiencing social instability received less NH than did infants residing in stable groups (β = −0.844, SE = 0.350, z = −2.414, p = 0.016; Figure 3a). Male infants received more NH than did female infants (β = 0.659, SE = 0.324, z = 2.033, p = 0.042; Figure 3b). Infants living in larger groups received more NH than those living in smaller groups (β = 0.471, SE = 0.223, z = 2.110, p = 0.035; Figure 4a). Infants did not vary in NH time based on the presence of maternal siblings (β = 0.479; SE = 0.427, z = 1.123, p = 0.262) or cohort size (β = −0.491, SE = 0.262, z = −1.875, p = 0.061). There was no interacting effect of group size and cohort size (β = 0.077, SE = 0.297, z = 0.259, p = 0.796).

Time spent engaging in non-nursing TH (“TH-”) was predicted by group size, cohort size, group stability, and the interacting effect of group and cohort sizes (Figure 3, Figure 4). Infants had higher non-nursing TH time when residing in groups that were larger overall (β = 0.485, SE = 0.173, z = 2.806, p = 0.005; Figure 4a) or that had smaller infant cohort sizes (β = −0.576, SE = 0.188, z = −3.061, p = 0.002; Figure 4b). The negative effect of cohort size on non-nursing TH time was amplified by the effect of group size, such that infants residing in overall larger groups had a stronger negative association between cohort size and non-nursing TH time (β = 0.480, SE = 0.192, z = 2.506, p = 0.012). Infants residing in unstable groups engaged in less non-nursing TH time (β = −0.980, SE = 0.272, z = −3.597, p < 0.001; Figure 3a). TH- time was not predicted by presence of maternal siblings (β = −0.257, SE = 0.388, z = −0.661, p = 0.508) or infant sex (sex = male: β = 0.515, SE = 0.352, z = 1.463, p = 0.143). Time spent engaging in all TH behaviors (including nursing, “TH+”) was predicted by only one variable – group size, such that infants participated in more TH+ when residing in larger groups (β = 0.246, SE = 0.077, z = 3.181, p = 0.001; Figure 4a). No other variables were associated with TH+ variation (sibling presence = yes: β = −0.273, SE = 0.149, z = −1.827, p = 0.068; cohort size: β = −0.142, SE = 0.108, z = −1.322, p = 0.186; infant sex = male: β = 0.002, SE = 0.121, z = 0.014, p = 0.989; group stability = unstable: β = −0.197, SE = 0.149, z = −1.320, p = 0.187; group size*cohort size: β = 0.205, SE = 0.130, z = 1.574, p = 0.115).

4 DISCUSSION

Nonmaternal infant handling is widespread and frequent in colobines relative to other nonhuman primates (Hrdy, 1976; Maestripieri, 1994; McKenna, 1979), and black-and-white colobus fit this pattern (Bădescu et al., 2015; Brent et al., 2008). Even so, total handling represented less than half of an infant's sampling time on average, which serves as a reminder that the time infants spend independently and socially within their cohort are key aspects of infancy that are missing from our picture of this life history stage without an infant-centered approach. Further, within our study, infants cumulatively engaged in 18 times as much handling time with mothers as they did with nonmothers, emphasizing that NH represents a minute fraction of the total handling infants receive. Reflecting this, TH time is predicted by MH time, but not NH time. The implications of this disparity are two-fold: first, as we found in our study, MH contributed so heavily to TH that the two measures were nearly equivalent; and second, we did not observe any instances in which infants with high participation in NH were able to successfully “counteract” reduced MH time.

Despite NH being relatively limited in terms of its actual duration, we acknowledge that NH likely offers unique social benefits. While a direct assessment of potential social benefits was outside the scope of our study, NH variation patterns were not fully aligned with TH variation patterns; this adds support to the possibility that when infants engage in NH, they experience social functions which are unique from those offered by mothers alone. In our study, infants overwhelmingly spent MH time engaging in nursing or holding behaviors whereas NH time was more evenly split between holding, grooming, carrying, and playing, further suggesting that the two handling sources may have separate utilities for infants. Potential benefits from early interactions with group members may include seeding an individual's social network and strengthening social bonds within the social group (Dunayer & Berman, 2017; Palagi, 2018). Still, the fact that infants spent such limited time engaging in NH (as compared to MH) is important. MH is the only source of handling with enough magnitude to determine whether an infant receives relatively high or low TH overall, as any individual differences in NH that do exist are dramatically overshadowed by the scale of MH.

Up to now, MH and NH have been studied in isolation from one another, but for infants, these forms of care exist within the broader context of one another and probably interact dynamically. Our findings do not support the hypothesis nonmaternal handlers “substitute” as care providers when mothers are unavailable. In our study, infants did not engage in NH interactions as a replacement for non-nursing MH time, even in our youngest age group (0–6 months). Instead, we observed the opposite trend in our youngest age group – infants who received high non-nursing MH also received high NH. Meanwhile, young infants receive less NH when nursing more, suggesting a possible trade-off between nursing and socializing with nonmaternal handlers. Black-and-white colobus infants do not scale back on non-nursing MH to participate in NH, and they do not typically allonurse; taken together, there is little evidence for NH replacing MH in this population. Links between MH and NH time disappeared as infants gained mobility and independence, as neither of the two older groups had any association between amounts of MH and NH received. The positive association between non-nursing MH and NH during early infancy suggests that during this critical developmental window, individual infants are experiencing markedly different social environments, such that some infants receive high volumes of handling from both mothers and others, while some receive comparatively little from either. It remains to be seen what the long-term impact of these differences may be. It bears noting that given the connection between these two handling types during early infancy, it would be difficult to untangle whether any long-term impacts of high levels of handling during early infancy are primarily tied to MH, NH, or a combination of the two.

Mothers are known mediators of early infant social networking in primates, with mothers helping infants establish connections and often imparting biases regarding preferred social partners based on her own bonds (Berman et al., 1997; Tomasello et al., 1990). Stemming from this, one possible explanation for the positive association between handling types in early infancy is that mothers who tend to socialize more within their group also happen to be more amenable to social interactions with their own infants (i.e., MH). If this is case, infants may benefit from a greater proportion of time spent in proximity to other group members, yielding them more regularly accessible for NH (as in Cercopithecus mitis stuhlmanni: Förster & Cords, 2005; Thompson & Cords, 2020 and Macaca fuscata: Sekizawa & Kutsukake, 2022). Compared to non-nursing MH, nursing is more likely to coincide with feeding and resting time for mothers—times when mothers tend to maintain more distance or be less actively engaged with social partners (Saj & Sicotte, 2007). As such, it is possible that the observed trade-off between nursing and NH stems from having fewer opportunities for maternally-mediated social exposure to nonmaternal handlers. Several studies of wild primates have described associations between higher maternal sociality and increased infant survivorship (Kalbitzer et al., 2017; McFarland et al., 2017; Silk et al., 2003, 2009) or faster infant development (Schneider-Crease et al., 2022). Although our study was not designed to address these, we suggest that increased handling from both mothers and nonmothers (i.e., high TH) during early infancy offers a potential proximate mechanism for these patterns.

Another, non-mutually exclusive possible explanation for the positive association between MH and NH during early infancy is that some infants are simply more attractive to both mothers and nonmother handlers based on individual features or heightened vulnerabilities. However, we did not observe this to be the case based on the characteristics we tested in our study. Male infants received greater amounts of NH time, and this aligns with previous descriptions of NH frequencies in our population (Bădescu et al., 2015; Brent et al., 2008). Previously it was hypothesized that handlers may be attracted to these infants based on male infants’ increased risk of infanticide in this population (Bădescu, Wikberg, et al., 2016; Sicotte & Teichroeb, 2008). When we added MH behaviors to the data set (“TH-” and “TH + ” models), infant sex did not predict TH. This suggests that if NH does play an infanticide-prevention role in this population, it is unique to nonmaternal handlers and the benefits of a wider social network specifically, as mothers did not also alter their handling time in response to infant sex.

Collectively, our results do not appear to support the hypothesis that handling is a protective measure for infanticide prevention in this population, given that mothers—who are most invested in infant survival—did not alter handling in response to infanticide risk. Infants received less NH when their social group experienced “unstable” male membership. When acute threats are actively present, infants receive less NH time, possibly because mothers are more protective of infants in more precarious social contexts (Cercopithecus aethiops: Fairbanks & McGuire, 1987; C. vellerosus: Brent et al., 2008; Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii: Scott et al., 2023). Though we have not evaluated rates of maternal rejection of NH attempts in this study, our results suggest that mothers are not necessarily increasing their protectiveness during periods of male membership instability; for instance, when we added non-nursing MH behaviors to the data set (“TH−” model), we found that infants also receive less non-nursing handling from mothers during unstable periods. With nursing behaviors included in the data set (“TH+” model), group stability no longer predicted the amount of total handling infants received. These results may reflect inhibited expression of maternal care during periods of higher maternal stress, as has been described in other primates (Saltzman & Maestripieri, 2011), or a slight redistribution of maternal care to increased time nursing when mothers experience higher glucocorticoid circulation (Malalaharivony et al., 2021).

Infants did not alter their engagement in any form of handling based on whether any maternal siblings co-resided in the social group. This is unexpected, since it is a common trend across primates that close relatives handle infants more frequently than other group members (Dunayer & Berman, 2018), as they likely experience inclusive fitness benefits (Riedman, 1982) and mothers may be more tolerant of infant access attempts made by related individuals (Berman, 2004). Indeed, previous analyses of NH in this population identified a similar maternal kin bias (Bădescu et al., 2015). Our results suggest that while infants may engage with these handlers more frequently, handling by siblings—who are often immature—may be of relatively short durations, such that more bouts with siblings do not add up to significant amounts of cumulative NH time. While maternal sibling presence did not appear to be a boon for NH time, neither did it detract from MH time. TH was unaffected by sibling presence; as such, it does not appear that infants compete with siblings for maternal engagement in this population. This may be related to flexible dispersal patterns in black-and-white colobus, whereas species with strict female philopatry may benefit from more intense, long-term investment in the social bond between mothers and weaned daughters (van Noordwijk, 2012) with a higher potential for intensified sibling competition.

Like maternal siblings, the presence of additional infants in the social group simultaneously represents a potential well of preferred social partners and possible competition for handlers’ time. As it happens, NH was unaffected by both infant cohort sizes and the interaction between group and cohort sizes, suggesting the competition for nonmaternal handlers is not an issue for infants in this population, even in small groups with relatively large cohorts. Colobus infants can invest in peer bonding without sacrificing handler networking, possibly because NH represents such a small fraction of infants’ total time budget. The same is not true for handling by mothers; as infant cohort sizes increased, infants engaged in less non-nursing MH time. This trend suggests that when peers are more readily available, infants rely less on mothers being active social partners, and consequently have reduced overall participation in handling. The effect of cohort size on non-nursing TH was further amplified when group size was accounted for; infants belonging to large cohorts reduced TH participation to an even greater extent when also living in a large group.

Larger group sizes were associated with higher NH time, and this is likely a simple reflection of greater availability of potential handlers in terms of both number and proximity. Life in larger groups generally includes more nearby bodies; infants who reside in larger groups may maintain moderate proximities to a greater number of group members in any given moment (Berman et al., 1997), lending them more likely to participate in NH when more individuals are within reach. Group size also predicted TH time (regardless of whether nursing durations were included), suggesting that as group sizes increase, infants increase nursing time in addition to social engagement with nonmothers and mothers. In rhesus macaques, infants increase time in contact with mothers to protect against elevated social risks associated with higher proportions of unrelated individuals in the group (Berman et al., 1997). Yet, this does not appear to play a role in driving increased TH in this population, probably because black-and-white colobus monkeys regularly live in groups with a high proportion of unrelated and non-natal females (Wikberg et al., 2012). However, colobus monkeys do experience higher scramble feeding competition when residing in larger groups (Saj & Sicotte, 2007). It is possible that additional nursing time may aid infants in buffering the effects of increased scramble competition. Developmental responses to scramble competition in primates are still poorly understood, but there is some evidence for altered nursing patterns in response to group size; for instance, Phayre's leaf monkeys residing in larger groups wean at a later age (Borries et al., 2008).

Overall, we found that increases in nursing time—unlike increases in NH—have the capacity to alter an infant's TH volume, highlighting that analyses of nursing variation may serve as a better proxy of total handling patterns than would analyses of NH variation. While we identified several predictors of NH variation, as MH was added to our models, the effect of these predictors weakened. As such, we would encourage future assessments of NH to co-consider MH, as this helps to contextualize variation in handling participation. Together, our model results emphasize that the adoption of a layered, holistic approach to handling research has the power to add depth to our understandings of adaptive primate development.

4.1 Conclusion

Infant handling by mothers and nonmothers are often evaluated as if they are isolated phenomena. By shifting our perspective to that of the infant, it becomes apparent that they may simply be two potential pools from which to receive the care and social networking necessary for a young primate's growth and survival. With this novel approach, we contextualize the relative contributions of each handling type to the total amount of handling infants receive. In theory, mothers are an infant primate's most impactful social partner; our study is one of the first to quantify and compare the time investments of mothers versus other handlers, revealing the full extent to which maternal handling has an outsized potential influence on infant development. For instance, in our study, only maternal handling patterns had the capacity to alter variation in the total amount of handling infants receive.

Our results challenge a potential notion that nonmaternal handlers serve the role of temporary replacement parents when mothers are otherwise occupied: increased participation in nonmaternal handling cannot compensate for deficiencies in maternal handling, and maternal and nonmaternal handling time was not correlated for most of infancy. The only association we did observe (during early infancy) was positive – infants with high participation in nonmaternal handling also had high maternal handling. Based on our results, we caution against extrapolating effects of high maternal or nonmaternal handling during infancy in isolation from one another without first assessing the relationship between the two handling types. When the two are positively correlated—as occurs in our population during early infancy—it is not be possible to discern if effects of increased handling are tied to more handling from mothers, nonmothers, or a combination of the two.

Overall, we found that variation in handling from mothers and nonmothers was driven by some similar features of the social environment, such as group size and stability. In other cases, the two forms of handling differed in responsiveness to surrounding environment and infant features. Together, our results suggest a complex, integrated relationship between sources of handling. Thus, the most significant benefit of an infant-centered approach is elevated nuance, such as the ability to distinguish between effects stemming from handler identity versus handling quantity, or the capacity to understand how the two sources interact and scaffold one another in response to social conditions such as group demographics or relative infanticide risk. Based on our results, we suggest that this methodology may bear utility for studying primate sociality beyond infant handling, such as elucidating proximate mechanisms for fitness effects associated with maternal sociality.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Allyson G. King: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Visualization (lead); Writing—original draft (lead). Tianna Rissling: Data curation (supporting); Investigation (equal). Susanne Cote: Supervision (equal); Writing—review & editing (equal). Pascale Sicotte: Conceptualization (equal); Funding acquisition (lead); Supervision (equal); Writing—review & editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the University of Calgary. We also thank the Boabeng-Fiema Monkey Sanctuary management committee, elders of the Boabeng and Fiema communities, and Ghana Wildlife Division who granted permission to conduct this research. We would like to acknowledge Robert Koranteng, Charles Kodom, Luke Larter, Tom Avant, Hannah McIntyre, Diana Christie, and Megan Ko for their contributions to field data collection. We also thank Jeremy Hogan, Dr. Shasta Webb, and Dr. Urs Kalbitzer for their statistical support as well as Dr. Josie Vayro for her field site support and mentorship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.