Social and familial context of prenatal genetic testing decisions: Are there racial/ethnic differences?

Abstract

The purpose of this cross-sectional study of 999 socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse pregnant women was to explore prenatal genetic testing attitudes and beliefs and the role of external influences. Surveys in English, Spanish, and Chinese included questions regarding the value of testing, pregnancy, and motherhood; the acceptability of Down syndrome in the subject's community; and the role of social and cultural influences in prenatal testing decisions. We analyzed racial/ethnic differences in all attitudinal and external influence variables, controlling for age, relationship status, and socioeconomic status. We found statistically significant racial/ethnic group differences in familiarity with an individual with Down syndrome and in 10 of 12 attitude, belief, and external influence variables, even after controlling for other sociodemographic characteristics. We also observed substantial variation within racial/ethnic groups for each of these measures. Despite the statistically significant group differences observed, R2 values for all multivariate models were modest and response distributions overlapped substantially. Social and familial contexts for prenatal testing decisions differ among racial/ethnic groups even after accounting for age, marital status, and other socioeconomic factors. However, substantial variation within groups and overlap between groups suggest that racial/ethnic differences play a small role in the social and familial context of prenatal genetic testing decisions. © 2002 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The use of genetic testing has become more prevalent as a result of human genome mapping, public interest in new genetic technologies, and pressure from industry to integrate new testing products into clinical practice. Many individuals first confront questions about the usefulness and value of genetic testing personally in the context of pregnancy and prenatal testing for Down syndrome. For this reason, a focus on prenatal testing for Down syndrome is an excellent place to begin to understand the social and familial context of genetic testing.

A focus on prenatal testing for Down syndrome is an excellent place to begin to understand the social and familial context of genetic testing

. Furthermore, although Down syndrome screening does not involve the potential for racial/ethnic stigmatization that can occur in the context of screening/testing for conditions such as Tay-Sachs disease or sickle cell anemia, the experiences of some groups with previous testing programs may have important impacts on current attitudes about testing [Nsiah-Jefferson, 1994; Moyer et al., 1999].

Although prenatal testing for Down syndrome and other congenital conditions has become a routine component of prenatal care in many communities, questions have emerged about how best to ensure that screening and diagnostic testing is widely available, equitably distributed, and offered in a way that respects the individual preferences of pregnant women. Early reports on the use of maternal serum AFP (α-fetoprotein) screening for neural tube defects noted that the way women were informed about the test, and the type of information provided, had a greater influence on testing decisions than did their ethnic or social backgrounds [Press and Browner, 1993]. These authors were concerned about the uniformity of response noted in women for whom AFP testing was offered as routine. In contrast, a 1996 report revealed significant racial/ethnic differences in test use among a group of women age 35 and over, all of whom had been informed about and offered testing for Down syndrome as an optional part of their early prenatal care [Kuppermann et al., 1996]. Although it is reasonable to expect that racial/ethnic differences in test choice might be observed, it is important that such differences reflect preferences and values rather than discrepancies in access to information or services.

Some of the observed differences in test use may be reflections of the social and familial context within which prenatal testing decision-making takes place, a context that includes cultural and religious beliefs. Other investigators' and our own unpublished work have shown that decisions about prenatal genetic testing are determined to a large degree by attitudes about abortion, miscarriage, and the value of life with a disability, all of which may be influenced by the woman's family and culture [Lippmann-Hand and Piper, 1981; Kaplan, 1993; Halliday et al., 1995]. To date, however, little work has emerged that clarifies the degree to which the social and family context of decision-making may impact the observed racial and ethnic differences in test use.

In this article, we explore attitudes toward testing and the role of external influences in a diverse population of pregnant women to better understand the social and familial context of prenatal testing decision-making. Our previous work has consistently revealed substantial within-group variation in attitudes about prenatal testing [Kuppermann et al., 1999, 2000; Moyer et al., 1999], in addition to differences in test use among racial/ethnic groups [Kuppermann et al., 1996]. We now seek to better understand how the social and familial context of decision-making varies across racial/ethnic groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Because our study aims were to compare attitudes and preferences among pregnant women of varied race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, we recruited subjects from a wide variety of clinical settings, including the university, HMO/private practices, and public prenatal care clinics. We included women of all ages and risk levels, not just those who were eligible under current guidelines for invasive prenatal genetic testing.

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we recruited women of less than 20 weeks of gestation who presented to one of several obstetrical practices in the San Francisco Bay Area and who could read or speak English, Spanish, and/or Chinese. Of 3,344 women screened from practice records for recruitment in 1997–1998, we successfully contacted 2,666. Of those contacted, 978 were ineligible due to gestational age over 20 weeks or no longer being pregnant. Of the 1,688 contacted and eligible women, 1,084 (64.2%) participated, 999 of whom were of African American, Asian, Latina, or Caucasian race/ethnicity and therefore were included in analyses for this study. Recruiters completed screening forms collecting minimum demographic information on the 999 participants and 689 nonparticipants.

Measures

The first 447 participants completed a detailed questionnaire on demographics, attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs about prenatal testing decisions and outcomes. Due to the addition of a series of computerized preference elicitation exercises, the remaining 637 participants completed an abbreviated questionnaire [Kuppermann et al., 2000]. Questionnaires were translated and back-translated into Spanish and Chinese. For participants preferring to be interviewed in their native language if other than English, a bilingual-fluent research assistant administered the questionnaire. Interviews were conducted in subjects' homes or at other convenient locations.

Demographic variables

We measured age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, annual household income, relationship status, and occupation using methods described elsewhere [Ostrove et al., 2000]. We asked respondents to indicate their race/ethnicity from a list of specified options, including the category of “other” followed by open fields. Prior to statistical analysis, the “other” responses were recoded using the established categories of African American, Asian, Latina, or Caucasian. Eighty-five responses were excluded from analysis either because they reflected mixed racial/ethnic identity or because they could not be coded into any of the four categories.

Social and familial context variables

We used seven-point Likert scales (strongly disagree to strongly agree) to measure participants' endorsement of a wide variety of attitudes and beliefs. Included among these questions were specific items assessing the familial, social, and cultural context of decision-making: attitudes concerning the importance of motherhood; acceptance of Down syndrome by oneself, one's family, and one's community; and the influences of family, faith/religion, and partner's wishes on decision-making. Participants who completed the abbreviated questionnaire were asked to indicate on four-point Likert scales (from “not at all influencing” to “completely influencing”) the extent to which specific individuals in their family and social network influenced their plans of whether or not to have prenatal testing: friends, partner or husband, other family members, health care provider, and religious leader. In sum, we included 12 items assessing the familial, social, and cultural context of decision-making. In addition, we asked participants whether they personally knew anyone with Down syndrome.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SAS (version 8.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We randomly selected the screening forms of 50 participants and 50 nonparticipants to assess potential demographic differences. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests and Wilcoxon tests and categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests. The primary analyses were designed to examine the associations of the main outcome variables—the 12 social and familial context variables—with racial/ethnic groups after adjustment for age, marital status, educational attainment, income, and occupation. Descriptive statistics were computed for all of the demographic and dependent variables stratified by ethnic group, including means, medians, and standard deviations for continuous data and frequency distributions for each of the categorical variables. Initial analyses were based on frequency tables of the outcomes and risk factors; chi-square tests and analysis of variance models were then used to gauge the degree of association. We used analysis of covariance models for the main hypotheses to compare mean differences in the social and familial context variables across racial/ethnic groups with continuous outcomes and logistic regression models for binary outcomes. Women without partners were excluded from analyses of racial/ethnic differences in partner influences on decision-making. A criterion probability level of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance assessing differences between the four racial/ethnic groups.

We calculated composite between-groups R2 from each analysis of covariance to estimate the contribution of race/ethnicity and all other demographic characteristics to the variation in our participants' responses to social and familial context variables. To create visual representations of variation within and between groups, we used spreadsheet software to plot separate distributions for each racial/ethnic group on the social and familial context variables.

RESULTS

We successfully recruited a sample with substantial racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity (Table I). Comparison of screening data on 50 randomly selected participants and 50 randomly selected nonparticipants revealed no statistically significant differences in age, weeks of pregnancy, educational attainment, occupational index, or racial/ethnic distribution.

| % (n = 999) | |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American | 18.0 |

| Asian | 26.0 |

| Latina | 22.0 |

| Caucasian | 33.9 |

| U.S.-born | 55.2 |

| College education or higher degree | 68.3 |

| Family income | |

| $25,000 or less | 31.1 |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 27.0 |

| $50,001–$100,000 | 27.3 |

| Over $100,000 | 14.6 |

| Employment | |

| Unemployed | 6.0 |

| Blue collar | 6.5 |

| Less skilled administrative | 13.5 |

| More skilled administrative | 21.0 |

| White collar | 34.9 |

| Professional | 18.2 |

| Married or living with partner | 82.9 |

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Social and Familial Factors

Familiarity with Down syndrome

Caucasians and Latinas were more likely to report knowing someone with Down syndrome (48% and 47%, respectively) than were African Americans and Asians (28% and 23%, respectively; P < 0.001).

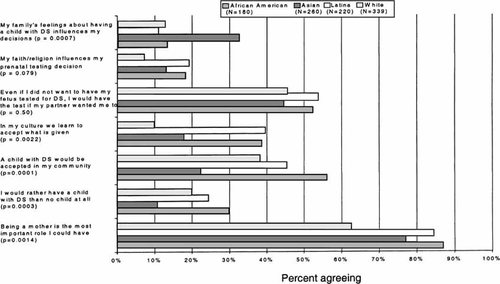

Attitudes toward Down syndrome, motherhood, and acceptance of outcomes

Comparing the level of agreement on social and familial context items revealed interesting patterns of differences between racial/ethnic groups after adjusting for age, relationship status, education, income, and occupation (Fig. 1). African American women were more likely than other women to endorse motherhood as the most important role a woman could have. Most participants from each racial/ethnic disagreed with the statement that they would rather have a child with Down syndrome than no child, and Asians were the most likely to disagree with that statement. Acceptance of a child with Down syndrome in one's community followed a similar pattern. African Americans and Latinas endorsed the statement that “In my culture we learn to accept what is given” the most, Caucasians the least, with Asians intermediate.

Percent of respondents endorsing attitude statements (agree or strongly agree) about social and familial factors in prenatal testing decision-making: African American (dark-gray bars), Asian (black bars), Latina (white bars), and Caucasians (light-gray bars). P values for racial/ethnic group differences are from logistic regression analyses controlling for age, relationship status, education, income, and occupation.

Influences by partner, family, and faith/religion

Overall, there was moderate endorsement by all groups for the statement that if the partner wanted the fetus tested for Down syndrome, the subject would accede to this request even if she did not want to be tested. (Approximately half of respondents in each group agreed or strongly agreed with this sentiment.) This item was the only social and familial context variable that did not differ between racial/ethnic groups. There was little endorsement by any group of the statement that faith/religion influenced their prenatal genetic testing decisions, and there was a statistical trend that Caucasian women were the least likely to agree with such a statement. Few women reported being influenced by their family's feelings about having a child with Down syndrome, but Asians were more than twice as likely as other groups to report such an influence.

Relative influence by specific individuals

All groups reported the highest levels of influence by partner or husband and health care provider and the lowest by friends and religious leaders, with family members intermediate (Table II). Statistically significant racial/ethnic group differences were identified for each potential source of interpersonal influence except for friends. Asians reported a significantly lower degree of influence by health care providers than did the other racial/ethnic groups. Latinas reported a significantly lower degree of influence by partner or husband than did the other racial/ethnic groups. Family influence was reported to be minimal in all groups, but highest in Caucasians and lowest in Latinas. Influence by clergy was minimal in all groups, but highest in Latinas and lowest in African Americans. There was a trend suggesting that Caucasians accept the influence of friends the most and Latinas accept it the least, with African Americans and Asians intermediate.

| How much do each of the following influence your plans whether or not to have prenatal testing?a | African American (n = 98) | Asian (n = 113) | Latina (n = 115) | Caucasian (n = 155) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My friends | 1.45 (0.06) | 1.38 (0.07) | 1.32 (0.07) | 1.58 (0.06) | 0.066 |

| My partner or husband (if applicable) | 2.59 (0.08) | 2.61 (0.10) | 2.31 (0.10) | 2.66 (0.09) | 0.024 |

| Other members of my family | 1.75 (0.07) | 1.68 (0.08) | 1.60 (0.08) | 1.95 (0.08) | 0.027 |

| My health care provider | 2.43 (0.08) | 2.11 (0.09) | 2.51 (0.10) | 2.63 (0.09) | <0.001 |

| My minister, priest, rabbi | 1.15 (0.05) | 1.31 (0.07) | 1.43 (0.07) | 1.30 (0.07) | 0.023 |

- * Adjusted mean (SE).

- a Likert scales from “not at all” influencing (1) to “completely” influencing (4).

- b Analysis of covariance controlling for age, relationship status, education, income, and occupation.

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Context: Individual Differences

Each racial/ethnic group, and the sample as a whole, expressed a wide variation in attitudes concerning social and familial aspects of prenatal genetic testing decisions. The variation among the participants can be divided into two components: variation attributable to race/ethnicity and other demographic differences (age, marital status, education, income, and occupation); and variation unexplained by race/ethnicity and other demographic differences and potentially attributable to other factors, including individual differences. The relative contribution of between-group and within-group variation is depicted in Table III. Despite many statistically significant differences between racial/ethnic groups, and after including other demographic differences, the majority of variation remains statistically unexplained.

| Variable (number of respondents) | % variation explained by race/ethnicity and other demographic variablesc |

|---|---|

| Being a mother is the most important role I could have (n = 917) | 10.5 |

| I would rather have a child with “Down syndrome” than no child (n = 910) | 7.8 |

| A child who had “Down syndrome” would be (readily) accepted in my community (n = 908) | 7.4 |

| In my culture we learn to accept what is given (n = 896) | 13.4 |

| Even if I did not want to have my fetus tested for “Down syndrome”, I would have the test if my partner wanted me to (if applicable; n = 906) | 1.9 |

| My faith/religion influences my prenatal testing decision (n = 876) | 4.1 |

| My family's feelings about having a child with “Down syndrome” influence my decisions (n = 432)a | 13.1 |

| How much do each of the following influence your plans whether or not to have prenatal testing (n = 481)b | |

| My friends | 4.2 |

| My partner of husband (if applicable) | 5.8 |

| Other members of my family | 9.9 |

| My health care provider | 9.2 |

| My minister, priest, rabbi | 6.2 |

- a This item was included only in the long version of the questionnaire.

- b This item included only in the abbreviated version of the questionnaire.

- c R2 from analysis of covariance for racial/ethnic differences controlling for age, relationship status, education, income, and occupation.

Plotting overlapping response distributions for each racial/ethnic group creates a visual depiction of differences that illustrates more information than mean comparisons. Despite the statistically significant mean differences reported above, there were striking similarities in endorsement for the importance of motherhood by each racial/ethnic group (Fig. 2) and, to a lesser extent, acceptance of a child with Down syndrome in the respondent's community (Fig. 3). A similar or greater degree of overlap was seen in the distributions of other social and familial context variables (not depicted).

Agreement with the statement “Being a mother is the most important role I could have” is plotted for each racial/ethnic group: African American (diamonds), Asian (squares), Latina (triangles), and Caucasian (Xs). For ease of interpretation, seven response levels are collapsed into three: disagree or strongly disagree; neutral, slightly disagree, or slightly agree; and agree or strongly agree.

Agreement with the statement “A child with Down syndrome would be accepted in my community” is plotted for each racial/ethnic group: African American (diamonds), Asian (squares), Latina (triangles), and Caucasian (Xs). For ease of interpretation, seven response levels are collapsed into three: disagree or strongly disagree; neutral, slightly disagree, or slightly agree; and agree or strongly agree.

DISCUSSION

We have found that race/ethnicity is associated with pregnant women's views on motherhood, attitudes on giving birth to a child with Down syndrome, and the degree of influence on prenatal genetic testing decisions accepted from partners, family, faith/religion, and health care providers.

We have found that race/ethnicity is associated with pregnant women's views on motherhood, attitudes on giving birth to a child with Down syndrome, and the degree of influence on prenatal genetic testing decisions accepted from partners, family, faith/religion, and health care providers.

The influence of race/ethnicity is present and statistically significant even after controlling for age, marital status, education, income, and occupation. However, racial/ethnic differences appear to explain only a relatively modest amount of the variation in pregnant women's attitudes toward testing, disabilities, and degree of external influence in decision-making.

We found that potential acceptance of a child with Down syndrome by our respondents and their communities was highest among African Americans and Latinas, who were also more likely than Asians and Caucasians to state that their faith/religion would influence the prenatal testing decision and that “accepting what is given” is part of their cultural belief system. These attitudes may help explain why African American and Latina women undergo prenatal diagnostic testing less often than Caucasian and Asian women and why age-specific rates of Down syndrome birth are higher among Latinas in California than other groups [Kuppermann et al., 1996, Hook et al., 1999].

African American women and Latinas diverged, however, in the degree of influence on the prenatal testing decision they ascribed to specific members of the clergy. Latinas were the group most likely to state that a religious leader could influence their testing decision, while African Americans were the least likely. This underscores the complex mechanisms that may exist to explain the interrelationship of faith, religion, and community leaders in shaping attitudes within a specific culture [Puñales-Morejon, 1997].

We also found that Asian women were far less likely than the other racial/ethnic groups to prefer a child with Down syndrome to no child and to agree that such a child would be accepted in their community. They were also more likely than the other groups to state that their family's feelings about having a child with Down syndrome would influence their decisions. However, the direction of family influence might differ among subgroups of Asian respondents. A population-based study in Hawaii showed that Asian Americans of Far Eastern ancestry were more likely than those of Filipina or Pacific Island ancestry to have an affected pregnancy prenatally diagnosed and undergo a pregnancy termination [Forrester and Merz, 1999]. The size of our sample does not support an analysis of the potential differences in the social and familial context of decision-making among subgroups of Asian Americans.

Caucasian women were less likely to endorse the notion that motherhood is the most important role that a woman could have and were the least likely to agree that their culture teaches them to accept what is given. Although women in all racial/ethnic groups were equally unlikely to agree to testing when their partner wanted them to and they did not, Caucasian women were more likely than other women to report that their partner or husband influenced their decisions. Caucasian women were the most likely to report that their health care provider would influence their decision-making, a finding that may reflect more trust for a health care system that shares more values in common with North American Caucasian women than with women of other cultures [Rapp, 1993].

It is interesting to note that Caucasians and Latinas were nearly twice as likely as African Americans and Asians to report knowing someone with Down syndrome, despite the fact that the prevalence is similar among all racial groups [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001]. It is unclear whether greater familiarity reflects more successful mainstreaming in some racial/ethnic groups or different interpretations of what “knowing someone” means in terms of closeness of affiliation.

Despite the significance of these differences, race/ethnicity and other demographic characteristics together explained less than 15% of the variance in each of the social and family context variables. Respondents within each racial/ethnic group expressed wide variation in their responses, and in many cases the response distributions overlapped far more than they diverged. These findings underscore the importance of acknowledging the heterogeneity within each racial/ethnic group. Overemphasizing statistically significant, but relatively modest, differences between groups could lead to erroneous assumptions when counseling women facing prenatal genetic testing decisions.

Our study has several limitations: little available information on eligible women who did not agree to participate, the restricted number of factors we addressed to explain differences among racial/ethnic groups, and the inability to distinguish subcultures within each racial/ethnic group. Although there could be a selection bias among our study participants compared with the general population of eligible pregnant women, the magnitude and impact of this bias are likely to be negligible. We found no statistically significant differences in the demographic characteristics of participants and nonparticipants. Nevertheless, there may be other differences in attitudes and beliefs that we could not compare and that could potentially affect the generalizability of our results.

We succeeded in recruiting women of diverse race/ethnicity and socioeconomic level from a wide variety of obstetrical practices. Achieving socioeconomic diversity within each racial/ethnic group enabled us to control for most of the demographic covariates that could possibly explain racial/ethnic differences in attitudes. We did not control or adjust, however, for whether participants were U.S.-born or not, or whether English was their preferred language (a proxy for acculturation), and their degree of trust or distrust for the health care system. For example, it is likely that more Latina and Asian women are first- or second-generation immigrants than African American or Caucasian women. It is therefore possible that some of the differences we have attributed to race/ethnicity could be explained by degree of acculturation. The influence of acculturation was addressed in part by our multivariate analyses to the extent that acculturation was associated with education, income, and other socioeconomic characteristics of our sample.

We used four general categories of race/ethnicity and did not distinguish potentially salient subcultures within each category. It is possible that the unexplained variation we observed within each group is a reflection of the diverse subgroups they comprise, rather than individual variation per se.

We used four general categories of race/ethnicity and did not distinguish potentially salient subcultures within each category. It is possible that the unexplained variation we observed within each group is a reflection of the diverse subgroups they comprise, rather than individual variation per se.

However, the heterogeneity within each of the racial/ethnic groups is also a strength of the study. All four groups encompass women from different cultural, religious, and social backgrounds and different socioeconomic levels. Teasing apart racial/ethnic differences from common demographic covariates is only possible in a study of such magnitude and diversity.

Finally, it should be noted that approximately 40% of the respondents completed a longer version of the questionnaire and 60% completed an abbreviated version. All items for which we pooled data from the two versions were measured using identical formats. No psychometric studies have investigated the effects of questionnaire length on the reliability and validity of specific measures, so the potential impact cannot be assessed.

In summary, although racial/ethnic differences exist in social and familial attitudes and influences on decision-making, these differences are dwarfed by the substantial variation that remains unexplained within each racial/ethnic group. Focusing exclusively on group differences could lead to inaccurate generalizations on how best to counsel women of different race/ethnicity about social and familial influences and their role in prenatal testing decisions. In contradistinction, understanding how social and familial factors inform individual preferences may help women (and their partners) make more informed prenatal genetic testing decisions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Bruce Blumberg and James Lewis for providing access to obstetrics patients at Kaiser San Francisco, Ana Fernandez-Lamothe for her dedicated research assistance, and all the women who participated in this study.