Psychiatric genetics researchers' views on offering return of results to individual participants

Abstract

In the middle of growing consensus that genomics researchers should offer to return clinically valid, medically relevant, and medically actionable findings identified in the course of research, psychiatric genetics researchers face new challenges. As they uncover the genetic architecture of psychiatric disorders through genome-wide association studies and integrate whole genome and whole exome sequencing to their research, there is a pressing need for examining these researchers' views regarding the return of results (RoR) and the unique challenges for offering RoR from psychiatric genetics research. Based on qualitative interviews with 39 psychiatric genetics researchers from different countries operating at the forefront of their field, we provide an insider's view of researchers' practices regarding RoR and the most contentious issues in psychiatry researchers' decision-making around RoR, including what are the strongest ethical, scientific, and practical arguments for and against offering RoR from this research. Notably, findings suggest that psychiatric genetics researchers (85%) overwhelmingly favor offering RoR of at least some findings, but only 22% of researchers are returning results. Researchers identified a number of scientific and practical concerns about RoR, and about how to return results in a responsible way to patients diagnosed with a severe psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, findings help highlight areas for further discussion and resolution of conflicts in the practice of RoR in psychiatric genetics research. As the pace of discovery in psychiatric genetics continues to surge, resolution of these uncertainties gains greater urgency to avoid ethical pitfalls and to maximize the positive impact of RoR.

1 INTRODUCTION

There is a growing international consensus that certain clinically relevant findings should be offered to individual participants in genomics research (MEXT et al., 2001; Bookman et al., 2006; Collins & Varmus, 2015; NHGRI, 2012; Fabsitz, McGuire, Sharp, Puggal, & Beskow, 2011; Genomics England, 2018; H3Africa, 2013; Indian Council of Medical Research, 2006; Jarvik et al., 2014; Middleton et al., 2016; NASEM, 2018; NBAC, 1999; Parliament of Estonia, 2000; Parliament of Finland, 2012; Weiner, 2014). However, return of results (RoR) is not a common practice in the field of psychiatric genetics and there is a dearth of empirical literature about how this issue should be managed in this field compared to other areas of genetics research (Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2018). The growing use of genomic testing in psychiatry research and the recently emerging body of knowledge about the genetic architecture of psychiatric disorders, brings this issue to the foreground in psychiatry research (Lee et al., 2013; McCarroll, Feng, & Hyman, 2014; Need & Goldstein, 2014; Ripke et al., 2014; Ripke, Sanders, & Kendler, 2011; Sullivan, Daly, & O'Donovan, 2012; Visscher, Brown, McCarthy, & Yang, 2012; Yuen et al., 2017). When using SNP arrays, whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing, psychiatric genetics researchers can generate clinically relevant information about risk, diagnosis, and treatment of psychiatric disorders (e.g., copy number variants; pharmacogenomic findings) and nonpsychiatric health conditions (e.g., risk for different types of cancer).

The way psychiatric genetics researchers manage these findings raises critical ethical, legal, and social issues that are common to other fields of genetics research. Such issues include financial and technical challenges, obtaining adequate informed consent, respect for autonomy including the participants' right to know or not to know genetic information, respect for the interests of participants' family members, difficulty in determining the pathogenicity of variants, and the potential for genetic discrimination (Evans, 2013; Fernandez, Kodish, & Weijer, 2003; Foster & Sharp, 2006; Green et al., 2013; Jarvik et al., 2014; Klitzman et al., 2013; McGuire, Knoppers, Zawati, & Clayton, 2014; Ravitsky & Wilfond, 2006). However, there are unique aspects of psychiatry and psychiatric genomics that may need to be considered when developing practical and ethically sound policies for this field, including: the polygenic nature of psychiatric disorders, the important role of environmental factors in psychiatry, the large sample sizes necessary to obtain significant findings in this field, the high prevalence of mental health stigma which increases the risk for discrimination, and the emotional impact that disclosing genomic findings may have on individuals who may be at risk or diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (Carson & Rothstein, 1999; Hoge & Appelbaum, 2012; Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2018; Singh & Rose, 2009). However, little empirical research exists to identify exactly what these issues are, and how they influence psychiatric genetics stakeholders' attitudes and perspectives about RoR and what are the pros and cons of RoR in this context.

Within the broader field of genomics, a number of studies have examined stakeholder's perspectives about RoR in genetics research. In one study, approximately 90% of respondents (including members of the public, genetic health professionals, and nongenetic health professionals) believed pertinent genetic findings and incidental findings that should be made available to research participants (Middleton et al., 2016). Another study found that 74% of a general public sample would like to receive genetics research results if they participated in a study (Kaufman, Baker, Milner, Devaney, & Hudson, 2016). A qualitative study by Kleiderman et al. (2015) suggested that genetics researchers believe a “one-size-fits-all” approach to returning incidental findings is inappropriate and that context needs to be considered.

Likewise, Sundby et al. (2017) found that psychiatric genetics stakeholders (i.e., patients with mental health disorders, their relatives, and clinicians) favor the return of both pertinent (95%) and incidental (91%) findings to research participants (Sundby et al., 2017), including to parents of child participants and to the children themselves when of legal age (Sundby et al., 2018). In another study, 97% of patients with a psychiatric disorder and unaffected relatives reported that they would like to be informed of any clinically relevant genomic findings generated in a study (Bui, Anderson, Kassem, & McMahon, 2014). Contrastingly, the default practice in genetics research has been not to offer RoR to individual participants (Klitzman et al., 2013; McCann, Campbell, & Entwistle, 2010; Ramoni et al., 2013). One study found that only 12% of researchers had returned incidental findings and another found that only 4% of GWAS had returned findings (Klitzman et al., 2013; Ramoni et al., 2013).

To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the views of psychiatric genetics researchers regarding RoR. Psychiatric genetics researchers are a key stakeholder group because they are at the forefront of knowledge about psychiatric genomics, often work directly with participants, and are the ones who generate and, to a large extent, control the management of genomic results. Therefore, understanding their perspectives is a critical first step to developing sound policies and guidelines for managing RoR in psychiatric genetics research, predicting impacts on participants and families, and even strategizing effective pathways for reporting results in the clinical setting.

2 METHODS

Using a semi-structured, open-ended interview format, psychiatric genetics researchers were asked their perspectives on pros and cons of returning results to individual participants in their research, including issues related to consent, choice, risks and benefits, related ethical issues and implications, and practical and ideological challenges. We chose the open-ended interview format to gather salient information about researchers' attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding RoR in psychiatric genetics.

2.1 Participant sampling

Participants were recruited via email, based on their membership in the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics (ISPG) and their involvement in ISPG committees, available online (https://ispg.net/membership/committees/). We initially recruited from these committees because we believed it would help identify experienced researchers (mid-career to senior) who may have more experience as principal investigators, and managing budgets and projects in which they had to decide whether to offer RoR or not. ISPG members were also recruited at the XXV World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics organized by ISPG in Orlando, FL in October 2017, through flyers and announcements in the conference program. We attempted to sample from a wide range of nations and included researchers and clinician-researchers using different types of genetic tests (e.g., SNP arrays, whole exome, and whole genome-sequencing; See Table 1). Interviews were conducted by three members of the researcher team, including the PI and two anthropologists (KK & SP) trained in qualitative interviewing. Interviews took place via phone, video conference, or in person at the XXV World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics in Orlando, FL in October 2017.

| Gender | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 14 (36%) |

| Male | 25 (64%) |

| Principal investigator status | |

| Yes | 37 (95%) |

| No | 2 (5%) |

| Country | |

| United States | 16 (41%) |

| Australia | 3 (8%) |

| Canada | 3 (8%) |

| Denmark | 3 (8%) |

| Germany | 3 (8%) |

| Asia | 2 (5%) |

| Other European Countries | 4 (10%) |

| North, Central, and South America, excluding United States and Canada | 5 (12%) |

| Educational background | |

| MD only | 16 (41%) |

| MD and PhD | 6 (15%) |

| PhD only | 16 (41%) |

| Other | 1 (3%) |

| Years of experience in psychiatric genetics research | |

| ≤ 5 years | 5 (13%) |

| 6–10 years | 8 (21%) |

| 11–15 years | 6 (15%) |

| 16–20 years | 10 (26%) |

| 21+ years | 10 (26%) |

| Types of genome testing conducted | |

| SNP arrays only | 18 (46%) |

| WGS/WES only | 9 (23%) |

| SNP arrays and WGS/WES | 9 (23%) |

| No genetic testinga | 2 (5%) |

| SNP arrays and Sanger Sequencing | 1 (3%) |

| Research focus by psychiatric disorderb | |

| Schizophrenia | 20 (51%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 13 (33%) |

| Depression and postpartum depression | 8 (21%) |

| Autism | 6 (15%) |

| Alcohol abuse and addiction | 5 (13%) |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) | 3 (8%) |

| Intellectual disabilities | 2 (5%) |

| Eating disorders | 2 (5%) |

| Dementia and Alzheimer's | 2 (5%) |

| No specific disorder (meaning all psychiatric disorders) | 2 (5%) |

| Others | 8 (21%) |

- Abbreviations: WGS, Whole genome sequencing; WES, Whole exome sequencing; SNP, Single nucleotide polymorphisms array.

- a These researchers conduct studies on genetic counseling and other issues related to psychiatric genetics but do not perform genetic testing.

- b Many researchers study different psychiatric disorders, thus the numbers under Psychiatric Disorder Focus are not mutually exclusive.

2.2 Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using MAXQDA software (Kuckartz, 2014). We developed a codebook collaboratively across three members of the research team who participated in coding and analysis. Of the 21 codes included in the codebook, nine were used to specifically search for themes related to researchers' attitudes toward the RoR in psychiatric genetics. We completed three rounds of coding before reaching consensus about the “fit” of codes to the data. To ensure integration of multiple interpretations of the data while utilizing researcher's diverse strengths (Moran-Ellis et al., 2006), all three coders coded a share of the data, with 25% coded by the PI, 75% by a research assistant (CB), and 100% by a medical anthropologist (KK) with expertise in qualitative methodology. We used thematic discourse analysis (Singer & Hunter, 1999; Taylor & Usher, 2001) to inductively (Frith & Gleeson, 2004) and iteratively (Polkinghorne, 2005) identify and refine themes, defined as patterned responses or stated/implied meanings concerning the research questions. We identified themes both qualitatively and quantitatively (e.g., frequency). Below, we present perspectives and attitudes toward RoR from among the aggregate of respondents, all of whom are currently involved in psychiatric genetics research. Findings are presented thematically, with some themes in Tables 2 and 3 reflecting arguments in favor and concerns that are common to other areas of genomic research; however, in the text, we focus on aspects specific to psychiatric genetics, as conveyed by respondents. Most of the RoR issues and concerns that are unique to psychiatric genetics came up in the arguments against and special considerations sections.

| Researcher origin | Quote |

|---|---|

| Benefits of knowing actionable and nonmedically actionable findings (56%) | |

| United States | If you are looking for medically actionable findings, you're almost obligated to [return results] if it's going to potentially impact that person's life. |

| Venezuela | If we have something to return and we have a positive thing to put in the hands of people, we should. Definitely. |

| Canada | [Returning results is] ethically the right thing to do. You can't sit on something that actually would have salience for somebody. The first thing you do is let them know. |

| Autonomy & ownership (49%) | |

| Costa Rica | I think the person should have all the right to decide what they want to know, what they don't want to know. |

| Switzerland | The strongest argument is [the results] belongs to you. It's your individual biological information [and] you have a right to have this information. |

| United States | They own that information. They are entitled to [it], and who are we to be the gatekeepers of it? |

| Reduction of stigma, guilt, or blame (13%) | |

| Norway | I think [some participants] like the idea that [an illness] is not their fault, it's their genes. |

| Australia | I think there is a hope that being able to let an individual know that the reason why they're unwell is because of a change in their genome and so it's not something that they've done personally or I think there's a hope that will alleviate guilt. |

| Reciprocity (8%) | |

| United States | Subjects have put themselves out to participate in the research [and]… the research community [should] think about their health in addition to thinking about them as research subjects. |

| United States | As taxpayers, [they're] spending money to generate genetic information on individuals that could either now or ultimately be leveraged to inform their care [and] we should share that information. We shouldn't make them go and get sequenced again. |

- * These themes reflect an overlap in arguments for RoR between psychiatric genetic researcher respondents and other areas of genetics research, and are not intended to be exhaustive of all arguments for RoR generally.

| Researcher origin | Quote |

|---|---|

| Negative emotional or behavioral effects | |

| United States | There are certain levels of stress that somebody might experience by receiving this information |

| Mexico | [There is a] nocebo response [whereby] our genetic tests might empower bad responses [which] might be to become anxious [if participants] understand that this is really a diagnosis. |

| Family disclosure | |

| Denmark | When you report back in genetics, you're not only reporting back to the individual, they're reporting back to basically an entire family. |

| United States | It's possible their family would not want to know that information. |

| Stigma, guilt, and blame exacerbated (36%) | |

| Costa Rica | In terms of social stigmatization, it has to be made clear to participants and to the population that you're not determined by your genes. |

| Australia | It might increase stigma [to say] the person has this sort of uncontrollable cause of… illness. |

| Results lack clear benefits or clinical applications (39%) | |

| Australia | There's no benefit in giving an unclear or uncertain message that might just worry a person and worry their families. |

| United States | People are relying on us to help them understand what something means. When we can't do that, it's dissatisfactory and can sometimes make the situation worse. I don't know what the right thing to do is. |

| Misinterpretation (33%) | |

| Switzerland | All you can do is calculate a certain risk based on the genetic factors that you know. I find it difficult for the individuals to cope with that risk [and] it's very different how people judge that risk. |

| United States | People respond very differently when you tell them they have a mutation which may increase the chance of developing a disorder by 10%. Some people may be scared to death. |

| Researcher burden (54%) | |

| United States | My priority is to keep doing our research and to spend our money right and to keep my staff employed and generate results. |

| United States | A lot of psychiatric genetics researchers don't know medical genetics and haven't had that as part of their training. Certainly I don't know enough medical genetics to do this on my own, so I rely on medical geneticists to help me. There is a limited resource available for contacting participants, letting them know the information, providing the relevant counseling. |

| Cost (54%) | |

| United States | We have no resources to support this. We have no resources to provide interpretation. |

| United States | If it's up to the researcher to create that infrastructure and carry the cost of having clinically validated results, I think that would be a barrier. |

| Japan | To realize it, I think some more finance and support is needed. Because we need to repeat the experiment and we need to hire some additional staffs to obtain clinically relevant laboratory testing. |

- * These themes reflect an overlap in arguments for RoR between psychiatric genetic researcher respondents and other areas of genetics research, and are not intended to be exhaustive of all arguments for RoR generally.

3 RESULTS

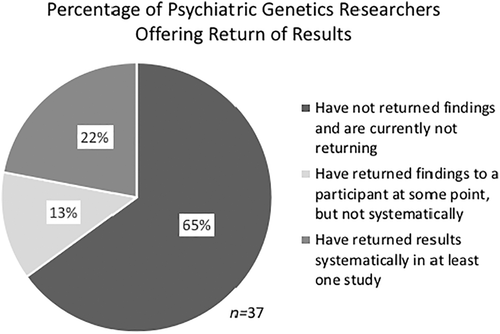

Respondents included 39 researchers in psychiatric genetics spanning 17 countries (Table 1). We found a robust emerging consensus in favor of offering results to individual participants: 85% of respondents agreed certain findings should be offered regardless of whether these are related to psychiatric or other health conditions. However, a vast majority of researchers (78% total) are either not returning results (65%), or have returned a result to a participant at some point in their research career but are not returning results systematically (13%). Only the remaining 22% of researchers are returning results systematically, defined as using a consistent policy in at least one of their studies, outlined in the participant consent form, and in which some type of result (e.g., medically actionable findings) is returned to individual participants (Figure 1). Of the 78% of researchers mentioned above who are not returning results or not returning them systematically, 21% said they have plans to return results systematically in future projects.1

3.1 Arguments in favor of returning results

3.1.1 Benefits of knowing actionable and nonmedically actionable findings

Many of the most salient arguments in favor of returning results in psychiatric genetics mirror those offered in the broader field of genomics research (see Tables 2 and 3). Most of the RoR issues and concerns that are unique to psychiatric genetics came up in the arguments against and special considerations sections. However, in this section on arguments in favor we also highlight issues that were specific to psychiatric genetics. The majority of psychiatric genetics researchers in our study (56%) considered the most significant potential benefit of returning results to be “actionability,” or the ability to use results to guide prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of a disorder, regardless of whether the genomic findings are associated with psychiatric or other health conditions.2 Over a quarter (28%) of respondents said they feel morally obligated to return results. One researcher from the United States explained, “I feel a duty as a researcher who's engaged with a participant to let them know if they're standing in front of a moving train [and] to rescue somebody from an imminent danger that they might not have the knowledge or ability to anticipate.”

As in other areas of genomics research, a majority of respondents felt that if a condition is preventable and treatable, results should be returned. Our respondents suggested that “actionability” in psychiatric genetics can mean treating psychiatric conditions directly or treating associated physical symptoms. For example, one researcher from the United States pointed out that individuals with a 22.q11 deletion “should really be taking calcium supplements for physical health reasons.” Another from Japan suggested that “in the case of bipolar disorder, [patients] with a static HLA type that [means] they're susceptible for Stevens-Johnson syndrome” then “it may be useful to return the results to patients.”

If you're thinking about influencing people's health behaviors or mental health behaviors, that's not as straightforward as how we think about [what is] medically intervenable. [For example], if you told somebody that they're at high risk for depression and should get regular exercise, have good sleep hygiene, these are all things that we know are beneficial for warding off depression. The intention there is to change behavioral health.

Some participants (18%) commented that receiving results can help individuals to plan accordingly. In cases of psychiatric disorder, specifically, respondents pointed out that receiving results can help individuals to prepare psychologically. One researcher from the United States said that individuals with existing psychiatric disorders “can seek help earlier and can try to figure out a way to live a less stressful life and lower their environmental risk factors. That may help them in their outcome.”

3.1.2 Autonomy and ownership

Consistent with arguments in favor of returning results in the broader field of genomics, a primary ethical concern among researchers was about participants' autonomy and control over the data (49%). A researcher from Japan stated: “it is the right of patients to know results of the study. The information obtained is a property of the subject.” A researcher from the United States said, “If I were a participant, I [would] feel this is part of myself that I have the right to, and no physician has the right to be saying ‘You don't have access.’” In the context of psychiatric genetics, however, the ethical imperative that participants should have autonomy over their data is complicated by uncertainties about participants' autonomous decision-making capacity. We address these concerns in the section 3.1.2 under section 3.2.

3.1.3 Reduction of stigma, guilt, or blame

Some researchers (13%) said that receiving results confers psychosocial benefits, such as a reduction in stigma or guilt (where genetic etiologies posit an external rather than internal locus of control). This finding is especially relevant in the case of psychiatric disorders, which typically carry significant stigma. As a researcher from Costa Rica pointed out “psychiatric illnesses are still like a separate category, and there's still a lot of exclusion, stigma, related to mental disorders.” Given existing assumptions about locus of control in psychiatry, some believed that results that posit genomic origins to psychiatric illness may help reduce stigma, guilt or blame for individuals. A U.S. researcher stated: “I actually do think that genomics has an inherently destigmatizing effect. So I think that it helps to reduce the level of blame and shame that people have.” A respondent from Australia echoed this perspective: “To let an individual know that the reason why they're unwell is because of a change in their genome and not something that they've done personally—there's a hope that will alleviate guilt.” Other respondents held an opposing view, that results showing genetic variants associated with psychiatric disorders might exacerbate rather than diminish stigma and guilt (see section 3.2).

3.1.4 Incentivize participation

Researchers also provided alternative rationales for RoR, including that returning results satisfies participants' incentives to participate and/or encourages participation (13%). One researcher said, “Many would actually appreciate it because that's why they participate in genetic studies,” while another pointed out that “[Participants] often put a lot of value on [receiving results] and see that as a worthwhile fringe benefit of participating in the study.” This is an especially important consideration for psychiatric genetics research, whose progress relies on large sample sizes and innovative approaches to participant recruitment and data aggregation.

3.2 Arguments against and concerns about offering RoR

3.2.1 Autonomy and ownership

We need to have a good understanding that people are willing and can give consent. That's particularly important in psychiatric populations. Somebody with a mental disability and general developmental disorder, somebody with profound psychosis, cognitively impaired. We need a special informed consent process.

It's not fair to hold patients hostage to their delusions… There are situations where we have provision, of course, for deemed consent and assent. But we cannot guarantee that we will not release results if there is some potentially serious consequence.

Others emphasized the need to assess participants' decision-making capacity immediately before returning results. “[What] if they're in an acute medical state,” asked one researcher from the United States. He continued, “Anytime you're dealing with a patient who's not in a particular position to handle their own data, the question [arises]: do we have to assess state of functioning at the time when we return results to them?”

Still, others rejected special considerations for psychiatric patients (see section 3.3), one researcher from Germany lamented, “I don't like it when we keep psychiatric patients separate from other patients, because that's a kind of stigmatization. We're looking at genes. Independent of whether you have cancer or you have a psychiatric disorder, [you] should be treated equally in [your] access to information.”

3.2.2 Negative emotional or behavioral effects

Psychiatric disorders are, by their nature, brain disorders, with different perceptions about the world, especially [in the case of] schizophrenia. The capacity to interpret the information given back to them would be different in a patient population versus controls.

Another researcher from Venezuela who referred to psychiatric populations as “higher risk people” said, “It's not the same to return results to one person who is very strong and very independent to someone who is absolutely pained and depressive and has a history of suicide attempts.” He continued: “You have people with high impulsivity. You have people with suicidality, with aggressiveness. This is something that you have to [consider]… People can take wrong any statement.” Another from the United States said, “We have highly anxious people, we have depressive people. They consistently take information more negatively than they should.” A researcher from Costa Rica suggested that “misinterpretation of results, and giving [results] a stronger value than what [they have], could… make the disease progress worse.”

A respondent from Germany who elaborated on the potentially negative emotional or behavioral consequences of misinterpretation, offered, “When [individuals] are suffering from symptoms, they are more vulnerable. This could put them under stress… do you want to run the risk that this information exacerbates something?”

If that individual [diagnosed with bipolar disorder] does not have any of [the expected] risk variants, then decides they actually don't have bipolar and stops taking medication, it creates a serious harm for individuals and their family. And a liability for the researchers and their doctors.

Maybe returning incidental findings to psychiatric patients should be looked at differently compared to somebody with a somatic disorder, because somebody who's very depressed might not deal very well with being informed that they have a BRCA1 mutation, for example.

This same researcher highlighted the potential burden on patients with existing psychiatric conditions who “might say, ‘Oh my god, I have a psychiatric illness, but also now I'm going to get cancer.’” Another from the United States said, “If you already have a psychiatric disorder, that you have additional problems looming in your genome may be additionally damaging.” Many researchers thus emphasized the need to “be careful” while returning results to participants with psychiatric disorders, even to develop tailored return procedures (see section 3.3 below).

3.2.3 Exacerbation of stigma, guilt, and blame

Over a third (14, or 36%) of respondents also identified psychosocial stigmatization as a primary concern when returning psychiatric genetics results. A respondent from Costa Rica commented about returning results related to psychiatric illness: “We worry a lot about if the research we do is going to increase stigma, or decrease it. It has so many implications for them socially.”

Take this situation where somebody is functioning just fine… then they're told they're at very high risk for schizophrenia. I think there would be concerns about how that person would then be treated and how they would perceive themselves even without having the disorder.

Some researchers explained that the concern about stigma stems in part from public and personal perceptions of control and blame, where genetic causes of the disorder are commonly viewed as out of a person's control, while psychiatric disorders continue to carry personal blame. A researcher from the U.S. argued that “The perception in society is still very much that psychiatric problems are [blamed] on the person who is experiencing them, rather than some combination of their genes and environment.” Another researcher from Australia suggested that even an acknowledgment of genetic causality may be stigmatizing, and “might in fact increase stigma… [to say] the person has this sort of uncontrollable cause of psychiatric illness.”

Researchers also commented on how psychiatric genetic findings may impact participants' feelings of guilt. A researcher from Canada commented that finding a genetic cause for a mental disorder like schizophrenia: “On the one hand, it will relieve guilt. On the other hand, it could make them feel demeaned in some way because of the stigma around psychiatric illness.” A researcher from Australia pointed out that these negative reactions can extend beyond the individual and argued that researchers should be aware “of the implications not only for the individual but for the family members, [and of] how much guilt can be carried with some of these results.” Another respondent from Venezuela pointed out that guilt may be particularly strong in cases of family disclosure, where someone may “feel guilty because maybe they transmitted [genetic risk] to the other [family member]… Can you imagine what this person thinks and feels, being psychotic?” Some respondents wondered if participants would experience “extra stress” knowing their relatives may have a disease, or guilt, “like they betrayed their affected family members.”

3.2.4 Discrimination

Related to stigma, other respondents shared concerns about data security issues regarding privacy, confidentiality, and exploitation (41%). Disclosure of an individual's risk for psychiatric disorder could be especially problematic given high rates of stigma against individuals with mental health disorders (see above). An Australian researcher pointed out the need to consider “issues around stigma and discrimination. It makes psychiatric research, psychiatric genomics, different to medical genomics.” A researcher from the United States pointed out that “loss of confidentiality [about a psychiatric predisposition] could lead to bias in health insurance [and] employment,” while other researchers brought up “participants' liability” (from Australia) and “securing privacy” (from Denmark) and “future genetic discrimination” (United States) as central concerns. A researcher from Norway expressed worry that findings will be forever documented in a participant's medical record. “What if we report an actionable finding to the clinician? Would that be on the medical record permanently?” Another researcher from Denmark implored, “We really need to take extreme measures so that we know who gets access and to what data.”

3.2.5 Difficult to interpret implications of psychiatric genetics findings

The worry about unintended malfeasance to individuals and families is compounded by the fact that many results in psychiatric genetics currently lack clear clinical relevance. Over a third (39%) of respondents suggested that returning results lacks clear benefits for individual research participants, especially in cases where results are not actionable (13%). Some respondents (23%) said they would not support returning results, until it was established that results lead to clear benefits or clinical impacts for individual participants, not only for aggregates or populations. This is especially important in cases where undue worry or anxiety might “trigger something” for psychiatric patients, said some respondents. As one researcher from the United States explained, “What we really want to do is improve the quality of life for patients who are suffering from mental illness. To what extent can we do that with return of genomic results? I think that's still unclear.”

The unique nature of psychiatric disorder is that there's not much known, definitively. There are some very strong genetic associations, or causal variation that's known to cause very severe genotypes, but then there's a lot that's just association, or it's just not clear what's going on, as opposed to cystic fibrosis, or some of the cancer mutations that are known.

Many researchers consider psychiatric genetics to be fundamentally different from other areas of genomics, “because we have a different level of complexity contributing to the disorders themselves,” suggested a researcher from the United States. Likewise, a Canadian researcher explained, “What makes the difference is that [psychiatric disorders] are so multifactorial and polygenic.” A respondent from Australia similarly said, “There is a genetic component [to psychiatric disorder], but also environmental components, and we lack understanding about the specificity of results and the risk associated with each individual variant.”

The lack of certainty surrounding genetic causality and penetrance contributes to moral reservations among some researchers (33% of our sample) about returning results when the state of psychiatric genetics cannot yet produce meaningful results. Some feel that psychiatric genetics has promised more information about actionable risk to patients and their families than the field is currently able to deliver. A researcher from India explained, “In psychiatry, we can't say with certainty [that] you will have this illness or not have this illness at this stage. So many things are interacting together, it becomes difficult to give the results to the patients.” A researcher from the United States similarly commented, “Until we understand more about the causes of psychiatric disorders, it will be difficult to return results.”

Some researchers (8, or 21%) rationalized that, given the strong potential to cause confusion or misinterpretation, fear, alarmism, and anxiety, it is unethical to return results that are nonmedically actionable or clinically relevant to patients seeking meaning in results. One researcher from Canada said, “There [are] very few things that are medically actionable right now with our understanding of psychiatric genetics. So, why are we telling people these things?” For many researchers practicing ethically responsible RoR in psychiatric genetics requires more evidence of genetic causality. A researcher from Denmark remarked, “[There's a lot of nonevidence-based thinking” and considered it “an ethical problem” in the field of psychiatric genetics.

3.3 Perspectives on special considerations for individuals with a psychiatric disorder

Three quarters of our respondents (30, or 77%) offered perspectives on whether norms and procedures for returning results should be different among individuals from patient groups versus controls, with more respondents than not (49% vs. 31%) stating at some point during the interview that they favor special considerations or plans for RoR to patient groups. Given respondents' beliefs about the greater likelihood for adverse emotional and behavioral reactions and misinterpretation of results to occur, many expressed support for special considerations for returning results to individuals with psychiatric disorders. Nearly half (18, or 46%) of all respondents discussed whether or not to engage in protectionism when returning results to psychiatric patients.

Some researchers, along with their institutional review boards, agreed that protectionism is warranted in some cases. For example, one researcher from Canada said, “[Our IRB] realized that there are situations where it may be appropriate to be somewhat paternalistic, to try and protect the patients.” If significant results are found, one researcher from Germany argued that “particularly with psychiatric patients, you need to make sure that when you return the results, they are [psychologically] well.” This stance was echoed by a researcher from the United States who suggested, “For some of the more severe psychiatric illnesses, it [is] important to make sure that a person is not in the middle of a psychotic episode or in the middle of a major depressive episode whereby somebody might become very fatalistic about some result they had received.”

It's this perception that because someone has a mental illness they don't have the capacity, which is often untrue, and this person is able to actually make this decision for themselves and have the capacity to deal with it. But there's kind of overarching paternalistic concerns that individuals with mental illness don't have that agency for themselves.

One researcher from Germany concluded, “we shouldn't be patronizing our participants.”

Over a quarter (12, or 31%) stated there should be no difference between psychiatric patients and controls with respect to considerations for returning results. A researcher from the United States stated: “I'm a big proponent for education and destigmatization of mental illness. I'm not in favor of most things that separate psychiatric illness from medical illness.” Another from Germany explained, “Whether you have cancer or you have a psychiatric disorder, I think they should be treated equally in their access to information.” A U.S. researcher put forth that, “Just because you have psychiatric illness doesn't mean you're walking around fragile all the time.” She continued, “Psychiatric exceptionalism is bad, very bad.”

I think there is potential need for more counseling intervention in psychiatric patients… but I think you have to be prepared even with healthy controls that the person may require some support and counseling.

4 DISCUSSION

The vast majority of psychiatric genetics researchers (85%) supported offering to return at least some results from psychiatric genomics studies, regardless of whether the findings are related to psychiatric disorders or other health conditions. However, only 22% of these researchers are actually returning results systematically. Many of the arguments in favor of RoR in psychiatric genetics overlapped with arguments for RoR in genomics research more broadly (Tables 2 and 3), although there were some issues unique to psychiatric genetics including that RoR may help reduce stigma, guilt, and blame. On the other hand, many of the concerns about RoR in psychiatric genetics research focused on issues that are particular to this field (see sections3.2 and ; 3.3).

Most researchers agreed that participants have a “right” to their data and that researchers have an ethical obligation to align return practices with participants' preferences. These findings support other studies of stakeholder's perspectives about RoR in genetics research generally (Kleiderman et al., 2015; Klitzman et al., 2013; Middleton et al., 2016). According to studies examining attitudes toward RoR in psychiatric genetics in particular (Sundby et al., 2017), stakeholders favored the return of both pertinent and incidental findings to individual research participants, mirroring opinions of our researcher respondents. As has been reported for researchers in other fields of genetics, psychiatry researchers in our study pointed out an additional benefit is that RoR incentivizes participation in studies that require very large sample sizes (Klitzman et al., 2013).

Psychiatry researchers emphasized actionability, or secondarily, medical relevance as an important factor in favor of offering RoR. Interestingly, actionability is generally used to refer to the availability of medical interventions that can help prevent or decrease poor health outcomes associated with a genomic variant (Dorschner et al., 2013; Jarvik et al., 2014). However, psychiatry researchers often used the concept to refer to opportunities for not just medical but also psychosocial and behavioral preparation or modification. There is a body of literature that supports that the general public values genomic information not just for its direct medical implications, but for its “personal utility” or its value for nonmedical reasons such as enhancing capacity to cope with health risks and ability to plan finances, housing and long-term care (Kohler, Turbitt, & Biesecker, 2017).

The view that conditions such as Alzheimer's and Huntington's, which are often used as classic examples of nonmedically actionable conditions, may actually be “actionable” was surprising and seemed to be supported by the view that things such as “regular exercise, …good sleep hygiene,” and other nonmedical interventions, such as the personal utility examples mentioned above, could help increase overall emotional well-being of the participant. This expansive view of actionability is not common among genomic researchers in other areas, in which actionability is generally used to refer to genomic conditions for which there is at least one preventive medical intervention available or some kind of treatment if the condition is expressed (Lázaro-Muñoz, Conley, Davis, Prience, & Cadigan, 2017). This finding raises an important issue to consider as the field of psychiatric genomics develops: based on this more expansive view of actionability, it is possible that researchers and clinicians in psychiatric genetics may be more willing to offer to return findings that individuals in other medical areas would not consider actionable.

Consistent with the broader literature on the role of genetic etiologies in exacerbating or reducing stigma, guilt or blame (Boysen, 2011; Boysen & Gabreski, 2012; Haslam, 2011, 2013; Kvaale, Gottdiener, & Haslam, 2013; Mehta, 1997; Phelan, 2005; Schnittker, 2008; Walker & Read, 2002), researchers from our study commented that this relationship is not straightforward. Some expressed that genetic etiologies have “an inherently destigmatizing effect” due to shifts in blame from a person (internal locus of control) to his or her genes (external locus of control). Others argued that discovering a potential genetic etiology may lead some to believe that an individual has an “uncontrollable” cause of illness (i.e., inevitable, immutable), which could increase mental health stigma and instigate negative emotional reactions that worsen existing psychiatric conditions.

Our respondents discussed other potentially negative emotional and behavioral consequences of returning results which seem to temper a more general enthusiasm for following participants' preference for full access and ownership over their results. Some researchers were concerned about creating a “nocebo” response, particularly in cases, where implications of the results are over or misinterpreted. Many researchers from our study suggested that these risks are amplified among individuals with psychiatric disorders that may predispose them to misinterpret or exaggerate findings more than controls, with significant potential for worsening existing anxieties, depression, or suicidality. There is debate about whether returning genetic findings causes emotional harms. The REVEAL study reported no significant increases in anxiety, depression, or distress to participants who had a parent with Alzheimer's, and were informed whether they carried an APOE variant suggesting an increased risk for Alzheimer's (Green et al., 2009). A number of meta-analyses show that individuals identified with BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants or at risk for Huntington's show a temporary increase in anxiety, and hopelessness, respectively (Crozier, Robertson, & Dale, 2015; Hamilton, Lobel, & Moyer, 2009). On the other hand, to our knowledge, no research has examined the emotional or behavioral impact of returning psychiatric or nonpsychiatric genomic results to individuals at risk for psychiatric disorders such as psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders or diagnosed with such disorders.

Finally, researchers suggested that psychiatric disorders often have more “complicated” (multifactorial, polygenic) etiologies than nonpsychiatric disorders (especially Mendelian ones), and their clinical validity and implications are often unclear. This, led some researchers' to question whether it is worth returning results that currently lack clear implications, benefits or clinical applications. While concern about the clinical utility of results is relevant to the broader realm of RoR in genetics research (Bredenoord, Kroes, Cuppen, Parker, & van Delden, 2011; Fabsitz et al., 2010; Jarvik et al., 2014; Meacham, Starks, Burke, & Edwards, 2010; Ravitsky & Wilfond, 2006; Sharp & Foster, 2006), its ethical relevance may be sharpened when returning results to participants with a psychiatric diagnosis because of the worry and anxiety that may “trigger something,” as one respondent suggested. On the other hand, many argue that we need to ensure that individuals at risk or diagnosed with psychiatric disorders are not unduly discriminated against and have the opportunity to benefit from RoR as much as others. A majority of respondents cited the above concerns to argue for the need for special considerations or protections for psychiatric recipients of results.

5 CONCLUSION

There seems to be a consensus among this sample of psychiatry researchers in favor of offering to return genetic results to individual participants, regardless of whether these are control participants or participants with a psychiatric disorder. Moving forward, it will be essential to formulate clear, practical, and ethically justified guidelines for RoR taking into account the particularities of this field and the perspectives of researchers and other stakeholders (e.g., participants, funding agencies, professional organizations). These guidelines should reflect empirical studies not only of stakeholders' perspectives, but of the impact of RoR on individual participants in psychiatric genetics research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the researcher-participants who kindly took the time to thoughtfully respond to these questions, Laura Torgerson for her assistance in the preparation of this article, and the reviewers for their helpful comments. Research for this article was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R00HG008689 (Lázaro-Muñoz, G). The views expressed are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect views of NIH or Baylor College of Medicine.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.