Social cognition as an RDoC domain

Abstract

While the bulk of research into neural substrates of behavior and psychopathology has focused on cognitive, memory and executive functions, there has been a recent surge of interest in emotion processing and social cognition, manifested in designating Social Cognition as a major RDoC domain. We describe the origins of this field's influence on cognitive neuroscience and highlight the most salient findings leading to the characterization of the “social brain” and the establishments of parameters that quantify normative and aberrant behaviors. Such parameters of behavior and neurobiology are required for a potentially successful RDoC construct, especially if heritability is established, because of the need to link with genomic systems. We proceed to illustrate how a social cognition measure can be used within the RDoC framework by presenting a task of facial emotion identification. We show that performance is sensitive to normative individual differences related to age and sex and to deficits associated with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Neuroimaging studies with this task demonstrate that it recruits limbic and frontal regulatory activation in healthy samples as well as abnormalities in psychiatric populations. Evidence for its heritability was documented in genomic family studies and in patients with the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Measures that meet such criteria can help build translational bridges between cellular molecular mechanisms and behavior that elucidate aberrations related to psychopathology. Such links will transcend current diagnostic classifications and ultimately lead to a mechanistically based diagnostic nomenclature. Establishing such bridges will provide the elements necessary for early detection and scientifically grounded intervention. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

THE DOMAIN OF SOCIAL COGNITION

The field of social cognition has seen a rapid growth reflected in over 19,000 publications listed in pubmed on that topic, nearly half (8,534) in the past 5 years and 457 in 2015 alone, and the year is not half through (retrieving the term “social cognition” from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed on April 21, 2015). Studies range from basic research, including animal models and basic human studies, to clinical investigations, which indicate the translational potential of the construct. It will obviously be beyond our scope to review this literature. Rather, we will outline the general progression of this work, focusing on findings relevant to the RDoC mission of elucidating psychopathology through dimensionally characterized behavioral domains.

In the broader context of psychology, Social Cognition has been a topic of study by social psychologists [e.g., Fiske and Taylor, 1991], and some concepts and paradigms have been productively adapted to clinical psychology, especially in relation to schizophrenia [see review in Penn et al., 2008 and chapters in Roberts and Penn, 2012]. Within cognitive neuroscience, social cognition has been defined narrowly and broadly. The narrow definition considers social cognition as a branch of cognitive psychology originating from the work of Neal Miller and Albert Bandura, who highlighted the role of modeling and motivation in learning. A broader definition considers the domain of social cognition to encompass behavior related to contact with the context of other conspecifics, and some would argue that other species should be included in the human's social environment. The field itself, as is usually the case, did not much consider definitional constraints. Studies include work on fear conditioning in rodents, affect discrimination in faces and voices in various clinical populations, measures of “empathy” and of “implicit bias,” and functional neuroimaging studies during activation with socially relevant stimuli ranging from faces to voices to moral dilemmas to simulated computer games (cyberball exclusion manipulation). The field reflects an intersection of cognitive neuroscience with “affective neuroscience,” and is characterized by convergence of data from animal to basic human to clinical studies, with neuroimaging as a major translational tool. The impact of this work spans clinical neuroscience, economics, social policy, and the legal system [Adolphs, 1999; Penn et al., 2008; Park et al., 2011; Cacioppo et al., 2014].

RELATION TO AFFECTIVE NEUROSCIENCE

While the main focus of linking behavior to brain function has been on “cold” cognition, and more specifically on language and memory, a more minor stream of evidence has accumulated about the “social” brain. Two influential investigators have called attention to effects of lesions on social behavior and emotion processing. Babinski [1914] reported on a series of cases with moderate to severe brain damage who either denied the existence of symptoms (“anosognosie”) or even were oddly happy, optimistic and jocular (“anosodysaphorie”). These patients had lesions in the right hemisphere. Babinski's contemporary, Jackson [1932], noticed the relatively intact social functioning of aphasic patients with left hemispheric lesions, concluding that it is the right hemisphere that regulates social cognition.

This methodology of clinical pathological associations has generated further evidence on neural substrates of social cognition related to hemispheric specialization. Most notable for case reports were the documentation of prosodic disturbance associated with right hemispheric lesion [Ross and Mesulam, 1979], and of deteriorating social functioning in a case of right frontal damage in a railroad worker [Damasio et al., 1994]. Aggregate case reports by Gainotti [1972] noted dysphoria and anti-social behavior with left hemispheric lesions, and jocularity and euphoria with right hemispheric lesions. Sackeim et al. [1982] reported retrospective studies of 119 cases of pathological laughing and crying associated with destructive lesions. Pathological laughing was associated with right-sided damage, whereas pathological crying with left-sided lesions. In 19 reports detailing mood following hemispherectomy, right hemispherectomy was associated with euphoric mood change. In reports of 91 patients with ictal outbursts of laughing (gelastic epilepsy), foci were predominantly left-sided. These case reports converged to suggest predominant role of the right hemisphere in mood regulation, with an overlay of left hemispheric involvement in positive affect. Other clinical-pathological association studies, closely linked with animal studies, have revealed the interplay between limbic structures and frontal control systems in regulating emotion and social behavior. Most notably, the Klüver and Bucy [1937] syndrome demonstrated the role of amygdala and hippocampal regions in emotional regulation. Patients with this syndrome, and primates with lesions in such limbic regions, show emotional lability and may vacillate between docile behavior and uncontrollable emotional outbursts.

The clinical case studies were complemented by animal and human laboratory studies that helped refine these hypotheses and generated rigorous measures linking social cognition to brain function. Studies used techniques such as visual half-field presentations, capitalizing on the projection of each visual field to the contralateral hemisphere [Natale et al., 1983]. For example, using chimeric presentations, Sackeim et al. [1978] found that emotions are expressed more intensely on the left side of the face, and that this effect is specific to negative emotions [Sackeim and Gur, 1978; Indersmitten and Gur, 2003]. Electrophysiological studies have supported the link between hemispheric functioning and emotion processing [Davidson et al., 2000; Gasbarri et al., 2007]. In addition to linking brain function to behavior, such studies have helped generate measures of social cognition and emotion processing that could be applied in the emerging methodology of functional neuroimaging.

Early functional neuroimaging studies of behavioral domains again focused on cognitive processes such as language, attention and memory, yet some findings relevant to social cognition did emerge. For example, mood induction effects were seen in a cortico-limbic system that correlated with subjective ratings [Schneider et al., 1994, 1995] and was triggered by the experience of confronting unsolvable anagrams [Schneider et al., 1996]. The introduction of functional MRI vastly accelerated mapping of social and emotional constructs into brain systems by introducing a safe procedure that yielded measures of regional brain activation. An outline of the main components of the social brain became clearer, implicating amygdala, orbitofrontal and ventromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex as its main hubs [Davidson et al., 2000].

The mounting capabilities and increased application of fMRI has propelled a vast expansion of the study of neural substrates for social cognition. Beyond characterizing common and separable brain systems for identifying facial and vocal emotions [Leitman et al., 2010], studies have examined social cognition domains such as moral judgment [Greene, 2015], sexual attraction [Bolmont et al., 2014], response to baby schema [Glocker et al., 2009], empathy [Bruneau et al., 2015; Rêgo et al., 2015], and deception [Langleben et al., 2005]. More recent studies have examined effects of risk taking and reward valuations, linking limbic with cortico-striatal pathways [Cox and Kable, 2014; Doll et al., 2015]. The overlap in activation between facial emotion identification tasks and other social cognition tasks underscores the need to define aspects of emotion processing with dissociable neuronal representations, such as facial feature perception relative to empathy. Results of such studies have yielded, and will continue to offer multiple behavioral measures related to social cognition that can link to specific brain systems and can serve as domain measures relatable to psychopathology as envisioned by the RDoC initiative.

It is noteworthy that constructs examined during functional neuroimaging may differ when examined outside of the scanner [Gur et al., 1992]. For example, Pinkham et al. [2012] found that performance on a trustworthiness task changed when evaluated during fMRI compared to a psychological laboratory setting. Likewise, the Social Cognition and Functioning (SCAF) study indicated that the psychometric properties of measures in neuroscience may differ when used in behavioral paradigms [Green and Penn, 2013; Kern et al., 2013]. It is also important to note that emotion identification may not be one construct, but multiple ones, especially when one compares identification of positive to negative emotions.

CRITERIA FOR RDoC DOMAINS

For a measure of social cognition to represent an RDoC domain it needs to be reliably tractable across several levels of analysis and extendable to basic and, ultimately, molecular genetic levels of analysis. Validating such a measure would require demonstration of adequate psychometric properties such as internal consistency and construct validity, and evidence for external validity such as association with known sources of individual differences like age and sex. Additional requirements for such a measure are, in the context of the RDoC vision, that it has been reliably coupled to activation in brain systems implicated in social cognition, that it is sensitive to the presence of psychiatric symptomatology and, finally, that it is heritable and thus likely to be linkable to genetic influences and mechanisms. Here we will illustrate such a measure, facial emotion identification.

THE FACIAL EMOTION IDENTIFICATION TEST

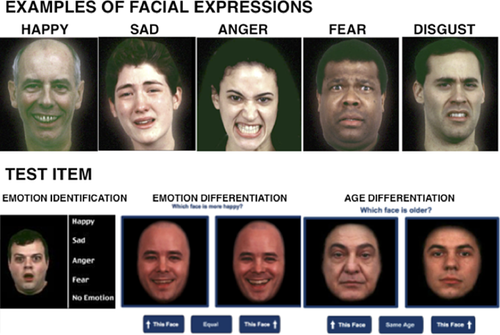

The task itself is straightforward: a face is presented that is either neutral or expressing an emotion and the participant chooses the appropriate label from an array of options. In our first implementation of the test, we used only happy and sad expressions and found substantial deficits in people with schizophrenia [Heimberg et al., 1992]. In depression we found a specific deficit of misidentifying neutral emotions as sad [Gur et al., 1992]. Subsequent implementation of the task extended the emotional expressions to include anger, fear and disgust [Gur et al., 2002a,2002b; Fig. 1]. In this format the test was administered with functional MRI and in large-scale genetic studies.

NORMATIVE VARIATION—SEX DIFFERENCES AND DEVELOPMENT

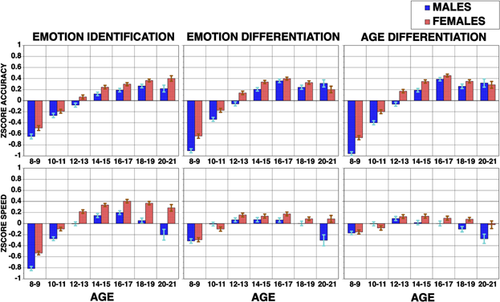

From early implementations of the test, sex differences were evident with females outperforming males and mobilizing fewer brain resources as indicated by more circumscribed activation in fMRI [Gur et al., 2002a,2002b]. This sex difference seems to extend to other social cognition tasks. For example, in the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort (PNC), a population based sample of youth ages 8–21 [Gur et al., 2012; Calkins et al., 2014], a comprehensive computerized neurocognitive battery [CNB, Gur et al., 2010] showed sex differences in cognitive performance where some domains (e.g., verbal memory) were performed more accurately and faster by females, others more accurately and faster by males (e.g., spatial processing), yet for other tests, one sex was faster and the other more accurate (e.g., attention, working memory). For the social cognition tests, which included emotion identification, emotion intensity differentiation and age differentiation, females performed more accurately and were faster on all tests [Roalf et al., 2014].

When examining the development of this ability, it is evident that there is great improvement from age 8 to age 21 in both accuracy and speed with large effect sizes (0.9–1.0). Nonetheless, females outperform males starting in childhood and the difference remains stable throughout early adulthood and even increasing for speed. A similar pattern is seen for the other social cognition tests in the CNB (Fig. 2). Thus, the emotion identification test is sensitive to normative individual differences in performance as affected by age and sex.

Emotion identification is associated with recruitment of a well-established brain system for emotion processing, centered around the amygdala. Human lesion and neuroimaging studies have documented the role of the amygdala in arousal and anxiety [Campbell-Sills et al., 2011] mood [Dyck et al., 2011], emotion identification [Gur et al., 2002a,2002b; Loughead et al., 2008; Derntl et al., 2009], social affiliation [Carter and Pelphrey, 2008] and threat perception [LeDoux, 2003; Guyer et al., 2008; Feinstein et al., 2011]. Identification of emotional content of a face is a fundamental social process [LeDoux, 2000, 2003]. Neuroimaging studies in healthy people have delineated a circuit involved in facial affect perception, including fusiform, temporolimbic and frontal regions, such as amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and insula [Haxby et al., 2000; Vuilleumier and Pourtois, 2007; Harris et al., 2014]. While amygdala responses have been linked to processing of stimulus salience and both positive and negative valence [Zald, 2003], convergent evidence suggests that the amygdala plays a unique role in the perception and processing of threat-related signals [Phelps and LeDoux, 2005; Fitzgerald et al., 2006]. Consistent with animal studies of fear conditioning [LeDoux, 2003], the amygdala responds to potentially threatening social signals, such as angry or fearful faces [Gur et al., 2002a,2002b; Mattavelli et al., 2014]. Thus, the role of the amygdala is not specific to emotion perception and it plays a more general role such as assigning salience to events. Furthermore, aspects of this complex structure serve diverse behavioral functions and connect differentially to striatal and sensory or motor systems. Below we will summarize findings related to schizophrenia, where deficits in facial emotion identification have been documented, to illustrate how such a domain can anchor an RDoC framed investigation.

PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

An important requirement for a domain to be compatible with the RDoC vision, is that deficits are associated with psychopathology. Social-affective neuroscience has been considered as offering pathways to elucidating neuropsychiatric disorders, where social behavior and emotion processing and expression are impacted [Cacioppo et al., 2014]. In most psychiatric disorders difficulties in social functioning are evident and the underlying neural processes and systems have been examined.

The RDoC approach provides a new framework for translational work on deficits in social cognition [Insel et al., 2010]. The phenotypic features of social cognition implicate several complementary social-emotional dimensions-negative/positive valence, intensity/arousal and social approach/avoidance.

SCHIZOPHRENIA

Schizophrenia is characterized by positive and negative symptoms and by cognitive and affective deficits. While positive symptoms have traditionally been the focus of investigation, others and we documented neurobiological abnormalities related to negative symptoms and social-emotional deficits. Negative symptoms are a central feature of schizophrenia [American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Kirkpatrick et al., 2006], with clinical significance demonstrated by independence of other symptoms [Blanchard and Cohen, 2006, Harvey et al., 2006; Keefe et al., 2006], relation to functional impairment [Bellack et al., 1990; Mueser et al., 1990; Fenton and McGlashan, 1991; Horan and Blanchard, 2003; Milev et al., 2005; Lyne et al., 2015] and presence in neuroleptic naïve patients [Shtasel et al., 1992; Siegel et al., 2006; Lyne et al., 2015]. Longitudinal studies show limited improvement with first- or second-generation antipsychotics [Murphy et al., 2006; Subotnik et al., 2014; Üçok and Ergül, 2014] or even an optimized early intervention program by a 10-year followup [Secher et al., 2015].

Across medicine there has been a concerted focus on early identification of disorders where rapid intervention can favorably impact disease course. In recent years, a similar approach has been applied to schizophrenia with studies of adolescents and young adults who present with attenuated psychotic symptoms and might be at the prodromal phase of illness [Yung et al., 2003; Cannon et al., 2008; Ruhrmann et al., 2010]. While the possible inclusion of Attenuated Psychosis Syndrome in DSM-5 has been debated [Carpenter and van Os, 2011] it is noteworthy that the emphasis is on positive psychotic symptoms of delusions, hallucinations and disorganized speech. Yet, anxiety and depression are common features in the prodrome and the emergence of negative symptoms is, at times, misconstrued as depression [Rosen et al., 2006; Wigman et al., 2011]. Not only are lack of social engagement and diminished expressivity early warning signs, but they are part of the emerging illness that may precede the onset of attenuated psychotic symptoms and portend poor outcome [Häfner et al., 2003; Marchesi et al., 2015].

Affective features of schizophrenia, which may represent extremes of the dimensions highlighted above, have been related to amygdala function and circuitry [Aleman and Kahn, 2005; Gur et al., 2007a,b]. Individuals with schizophrenia are impaired in facial affect perception [Heimberg et al., 1992; Edwards et al., 2002; Gur et al., 2006; Kohler et al., 2010; Allott et al., 2015], especially for threat-related expressions of anger and fear [Evangeli and Broks, 2000; Edwards et al., 2001; Kohler et al., 2003]. These deficits are associated with severity of negative symptoms [Gur et al., 2007a, 2006]. Longitudinal studies indicate persistent impairment, with symptom remission marginally improving performance [Penn et al., 2000; Kee et al., 2003]. Indeed, deficits on the emotion recognition test had the highest effect sizes (>1.0) for both accuracy and speed in two large samples, the first family based and the second ascertained in a case-control design [Gur et al., 2015]. More recent work demonstrates that these deficits are present as early as the first-episode and are also observed in youths at clinical high risk (CHR) [Addington et al., 2006; van Rijn et al., 2011]. In a recent longitudinal study of CHR youths, the emotion identification test was the single best predictor of transition to psychosis [Corcoran et al., 2015 in press].

A recent study by Pinkham et al. [2015] compared the ER40 to six other tests of social cognition: Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire (AIHQ), Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (BLERT), Relationships Across Domains (RAD), Reading the Mind in the Eyes Task (Eyes), The Awareness of Social Inferences Test (TASIT), Hinting Task, and Trustworthiness Task. Tests were evaluated on test-retest reliability, utility as a repeated measure, relationship to functional outcome, practicality and tolerability, sensitivity to group differences, and internal consistency. While the ER40 was ranked overall below BLERT and Hinting, it is notable that only its overall accuracy score was used. Furthermore, issues such as practicality and tolerability have not been considered in the context of international genomic studies that make language-mediated tests like Hinting impractical.

The potential role of aberrant amygdala activity in the behavioral abnormalities of emotion processing in schizophrenia has been examined in two meta-analyses. One study observed under-recruitment of the amygdala regardless of whether the task was explicit or implicit, and independent of chronicity [Li et al., 2010]. The other study replicated reduced amygdala activation, but importantly found that this deficit was only present when directly contrasting emotional to neutral expressions. This conclusion is consistent with previous reports of amygdala overactivation to neutral expressions [Gur et al., 2002a,2002b; Hall et al., 2008]. Further supporting the amygdala overactivation hypothesis, we found that while healthy participants activated amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex more when a neutral face was seen previously as threatening, patients activated these regions equally to both previously threatening and non-threatening faces [Satterthwaite et al., 2010].

Variations in amygdala activity have been related to clinical features of schizophrenia [Pinkham et al., 2011a], particularly positive symptoms [Taylor et al., 2002, 2005] and the paranoid subtype [Williams et al., 2004; Pinkham et al., 2011b]. A smaller literature relating negative symptoms to amygdala activity has focused on flat affect [Fahim et al., 2005; Lepage et al., 2011]. Abnormally increased amygdala activation to fearful faces was associated with incorrect identification and with more pronounced flat affect [Gur et al., 2007a,b].

An understanding of amygdala function must also address interactions with other regions, as distinct circuits likely serve discrete roles in emotion processing and may relate differentially to symptom domains. Amygdala activation and connectivity was investigated in healthy people, schizophrenia patients and family members. Several limbic, striatal, thalamic, and cortical regions have been identified as constituting a “social brain circuitry” [Park et al., 2011]. In healthy people we observed increased amygdala functional connectivity with lateral orbitofrontal cortex and anterior insula in response to threatening facial expressions [Satterthwaite et al., 2011] and abnormally high amygdala-orbitofrontal cortex/insula functional connectivity in schizophrenia in a facial recognition task with neutral faces [Satterthwaite et al., 2010]. In contrast, ventral striatum and ventral pallidum preferentially respond to rewarding stimuli, and in healthy people we noted anticorrelated activity between amygdala and these regions during emotion identification [Satterthwaite et al., 2011]. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex-amygdala interactions have been implicated in “top-down” modulation of negative emotions and in extinction or reversal of previous aversive associations [Leitman et al., 2011]. Ventral prefrontal top-down modulation of facial emotion processing was reduced in schizophrenia [Kim et al., 2011]. Weakening of ventromedial prefrontal cortex-amygdala functional connectivity has been reported in schizophrenia during emotional identification [Fakra et al., 2008] during negative distraction in a perceptual task [Anticevic et al., 2012], and in resting BOLD data, where greater aggression was associated with weaker ventral prefrontal cortex-amygdala connectivity [Hoptman et al., 2010].

Abnormalities in amgydala activation and functional connectivity during emotion processing have also been reported in those at genetic or clinical risk for schizophrenia. Studies in first-degree family members reported elevated amgydala activity to emotional stimuli [van Buuren et al., 2011], normal activation during an implicit facial emotion paradigm [Rasetti et al., 2009], reduced activation during sad mood induction [Habel et al., 2004], and abnormally strong benzodiazepine-induced reductions in activation during emotion identification [Wolf et al., 2011]. Amminger et al. [2012] reported behavioral emotion identification deficits in both high-risk and first-episode subjects. Abnormal amgydala activation to fearful facial expressions and reduced prefrontal-amgydala functional connectivity were identified in fMRI studies of clinically psychosis-prone subjects [Modinos et al., 2010; Venkatasubramanian et al., 2010; Wolf et al., 2015].

These studies indicate that facial emotion identification and its underlying circuitry are dysfunctional in patients with schizophrenia and individuals at risk for schizophrenia. Thus, an index of emotion identification performance of the domain of social cognition could offer a continuous parameter that is measurable in healthy populations, is sensitive to normative variability related to sex differences and development, and yet differentiates patients with schizophrenia and those at risk for psychosis both in performance and in the activation of related brain circuitry. The remaining criterion for a measure to meet RDoC requirements as a potential domain that can be studied from the molecular to the clinical levels of analysis is association with genetic variability.

LINKS TO GENETICS

The likelihood that a behavioral measure will elucidate a mechanistic cascade from cellular-molecular processes to clinical phenomena is higher if there is evidence that it is heritable. Social cognition measures, including emotion identification, have been applied in large-scale genetic studies where they were examined as candidate endophenotypic measures [Knowles et al., 2015]. In several collaborative studies we have shown that heritability for emotion identification is significant and at least similar in magnitude to that observed for neurocognitive measures.

The multiplex multigenerational family study of schizophrenia showed estimated heritability of 0.373 for emotion identification efficiency [Gur et al., 2007a,b]. In an independent family study of African-Americans the heritability for emotion identification accuracy was 0.43 and for speed 0.21 [Calkins et al., 2010]. In a third independent family sample, emotion identification was also heritable and linked with other endophenotypes to several genes [Greenwood et al., 2011, 2013]. In the PNC sample we used genome-wide complex trait analysis to estimate the SNP-based heritability of each of the CNB domains.

Several domains, including emotion identification, suggested strong influence of common genetic variants [Robinson et al., 2015]. These preliminary results are encouraging. As progress in the field requires multiple levels of analysis, translational research in animal models benefits from converging paradigms, such as affiliative behavior, and additional measures of brain function, such as electrophysiology.

A complementary approach for elucidating gene effects on behavior is to study individuals with a known CNV that is associated with increased vulnerability to psychosis. In particular, CNV with relative higher frequency can be used to examine both common effects and those associated with variability in the deletion size and in intermediate phenotypes. The 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome (22q11DS) is an example of such a CNV and is associated with about 25% increase risk for schizophrenia with onset in adolescence and young adulthood. We examined emotion identification performance in a large sample of individuals with this deletion and found significant deficits already evident in youth [Gur et al., 2014]. Furthermore, fMRI studies indicate aberrant activation to facial stimuli [Andersson et al., 2008] and we found that amygdala overactivation was modulated by the emotion expressed [Gur et al., 2015]. Multiple psychiatric diagnoses are associated with 22q11DS, related to developmental stage. A translational approach to social cognition can advance efforts toward a mechanistic account that will likely transcend current diagnostic boundaries. Applying fMRI tasks designed to probe the underlying circuitry of emotion identification can help delineate the nodes in the circuitry that underlie these deficits. Such a dimensional approach can be complemented with mouse models that examine affiliate behavior.

Efforts by the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium have recently identified 128 established and novel loci in large samples of cases and controls [Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014]. Notably, common variants between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability were observed, buttressing the importance of examining common behavioral domains implicated in these disorders, such as social cognition. Classification along these dimensional measures will ultimately yield the mechanistically based diagnostic nomenclature.

PSYCHOSIS SPECTRUM DISORDERS

Since RDoC domains aim to examine constructs that relate to basic neurobiological processes, abnormalities would have implications across phenotypically defined disorders. The emotion identification test was applied in the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes. They reported progressively increased deficits compared to controls from bipolar disorder to schizoaffective disorder to schizophrenia. There was some specificity of effects related to the emotion, with proband and relative groups showing similar deficits for angry and neutral faces, while schizophrenia probands had deficits for fearful, happy, and sad faces [Ruocco et al., 2014]. This finding is consistent with the pattern of emotion identification deficits observed in relatives of probands with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders who had bipolar illness [Calkins et al., 2010]. Thus, emotion identification deficits are evident across psychosis and recruiting individuals to studies based on performance on social cognition measures could shade light on a spectrum of severe psychiatric disorders as envisioned by the RDoC.