Sapap3 and pathological grooming in humans: Results from the OCD collaborative genetics study†

Please cite this article as follows: Bienvenu OJ, Wang Y, Shugart YY, Welch JM, Grados MA, Fyer AJ, Rauch SL, McCracken JT, Rasmussen SA, Murphy DL, Cullen B, Valle D, Hoehn-Saric R, Greenberg BD, Pinto A, Knowles JA, Piacentini J, Pauls DL, Liang KY, Willour VL, Riddle M, Samuels JF, Feng G, Nestadt G. 2009. Sapap3 and Pathological Grooming in Humans: Results From the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Am J Med Genet Part B 150B:710–720.

Abstract

SAP90/PSD95-associated protein (SAPAP) family proteins are post-synaptic density (PSD) components that interact with other proteins to form a key scaffolding complex at excitatory (glutamatergic) synapses. A recent study found that mice with a deletion of the Sapap3 gene groomed themselves excessively, exhibited increased anxiety-like behaviors, and had cortico-striatal synaptic defects, all of which were preventable with lentiviral-mediated expression of Sapap3 in the striatum; the behavioral abnormalities were also reversible with fluoxetine. In the current study, we sought to determine whether variation within the human Sapap3 gene was associated with grooming disorders (GDs: pathologic nail biting, pathologic skin picking, and/or trichotillomania) and/or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 383 families thoroughly phenotyped for OCD genetic studies. We conducted family-based association analyses using the FBAT and GenAssoc statistical packages. Thirty-two percent of the 1,618 participants met criteria for a GD, and 65% met criteria for OCD. Four of six SNPs were nominally associated (P < 0.05) with at least one GD (genotypic relative risks: 1.6–3.3), and all three haplotypes were nominally associated with at least one GD (permuted P < 0.05). None of the SNPs or haplotypes were significantly associated with OCD itself. We conclude that Sapap3 is a promising functional candidate gene for human GDs, though further work is necessary to confirm this preliminary evidence of association. © 2008 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

SAP90/PSD95-associated protein (SAPAP) family proteins are post-synaptic density (PSD) components that interact with other proteins to form a key scaffolding complex at excitatory (glutamatergic) synapses [Scannevin and Huganir, 2000]. There are four highly homologous members of the SAPAP family, and a recent study found that mice with a deletion of the Sapap3 gene groom themselves excessively [Welch et al., 2007]. This grooming behavior appears similar in nature to that of wild-type mice but is much more frequent, leading to facial hair and skin removal in the absence of peripheral cutaneous defects [Welch et al., 2007]. Pathological grooming behavior has been hypothesized to be related to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)—in humans and other animals—in terms of phenomenology and possible selective response to serotonergic drugs [Leonard et al., 1991; Rapoport et al., 1992; Bordnick et al., 1994; Overall and Dunham, 2002; Graf et al., 2003; but also see Bloch et al., 2007], and this behavior in Sapap3 mutant mice led Welch et al. to perform a set of experiments testing the extent to which these mouse behaviors resemble OCD in humans. The Sapap3 mutant mice showed increased anxiety-like behavior in open field, dark-to-light emergence, and elevated zero maze tests, and 6-day fluoxetine treatment of these mice reduced both excessive grooming and anxiety-like behaviors [Welch et al., 2007]. Cortico-striatal circuits appear dysfunctional in persons with OCD [Graybiel and Rauch, 2000; Saxena and Rauch, 2000; Aouizerate et al., 2004; Swedo and Snider, 2004; Menzies et al., 2007]; thus, it is highly relevant that Sapap3 mutant mice also showed defects in cortico-striatal synapses in electrophysiological, biochemical, and structural studies. Furthermore, lentiviral-mediated expression of Sapap3 in the striatum prevented synaptic defects, as well as compulsive grooming and anxiety-related behaviors, demonstrating that loss of Sapap3 in the striatum is central to the behavioral phenotype of Sapap3 mutant mice. Given the confluence of these findings with what is known about OCD in humans, it was hypothesized that Sapap3 might be involved in the etiology of human obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders [Hollander and Benzaquen, 1997; Welch et al., 2007].

Human pathological grooming behaviors [i.e., pathological nail biting, skin picking, and hair pulling (trichotillomania) [Bohne et al., 2005]] are common in persons with OCD [Bienvenu et al., 2000; Richter et al., 2003; Hanna et al., 2005a], and they appear to be part of a familial OCD spectrum [Lenane et al., 1992; Bienvenu et al., 2000]. Although not all persons with OCD have a grooming disorder (GD), and OCD and GDs are not generally considered identical, the high within-person and within-family comorbidity among these phenomena may offer clues to the etiology of OCD.

OCD itself is a familial [Pauls et al., 1995; Nestadt et al., 2000b; Fyer et al., 2005; do Rosario-Campos et al., 2005; Hanna et al., 2005b; Grabe et al., 2006] and heritable condition [Inouye, 1965; Carey and Gottesman, 1981; Nestadt et al., 2000a; Hudziak et al., 2004; van Grootheest et al., 2005]. However, molecular genetic studies of OCD are in their relative infancy, as are molecular genetic studies of GDs. The purpose of the current study was to determine whether variation within the human Sapap3 gene is associated with GDs and/or OCD in families collected for OCD genetic studies. As the mouse and human Sapap3 genes are highly homologous (>90%), the basic science findings of Welch et al. (2007) make Sapap3 an interesting functional candidate susceptibility gene for human GDs and, perhaps—by extension, OCD. The two prior linkage studies of OCD do not support Sapap3 (located on human chromosome 1p) as a positional candidate susceptibility gene for the OCD phenotype [Hanna et al., 2002; Shugart et al., 2006].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The OCD Collaborative Genetics Study (OCGS), described in detail elsewhere [Samuels et al., 2006], is a collaboration among investigators at several US institutions: Brown University, Columbia University, Harvard University (Massachusetts General Hospital), Johns Hopkins University (JHU), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the University of California in Los Angeles. JHU is the coordinating center for the study.

Sample Recruitment and Inclusion

The OCGS targeted families with OCD-affected sibling pairs, and extended these when possible through affected first- and second-degree relatives; in addition, two sites (JHU and Columbia) collected additional pedigrees with multiple affected relatives when available. We recruited participants from outpatient and inpatient clinics, community clinicians, web sites, media advertisements, self-help groups, and the Obsessive Compulsive Foundation. In the current study, we report on 1,618 participants from 383 families (mean 4.2 participants per family, range 2–17).

To be considered affected with OCD, a subject had to meet lifetime DSM-IV criteria. Probands were included if OCD symptom onset occurred before age 18 [early onset appeared associated with familiality in some studies [e.g., Pauls et al., 1995; Nestadt et al., 2000b; do Rosario-Campos et al., 2005] but not all [Fyer et al., 2005; Grabe et al., 2006]]. Probands with schizophrenia, severe mental retardation, Tourette's disorder, or OCD which occurred exclusively in the context of depression (“secondary OCD”) were excluded. Subjects had to be at least 7 years old to participate. Written, informed consent (or assent, for children) was obtained prior to clinical interviews. Institutional review boards at each site approved the protocol.

Clinical Assessment

Psychiatrists or PhD-level clinical psychologists conducted the diagnostic examinations using a semi-structured interview based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders [First et al., 1996]. The OCD section was adapted from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime Version Modified for the Study of Anxiety Disorders [Mannuzza et al., 1986]. We added a section to assess GDs, including pathological nail biting (PNB), pathological skin picking (PSP), and trichotillomania (TT). PNB and PSP are not DSM-IV diagnoses; as described in our previous work [Bienvenu et al., 2000], we modeled their diagnostic criteria after DSM-IV criteria for TT. We used the Family Informant Schedule and Criteria [Mannuzza et al., 1985] to obtain additional information about each subject from a knowledgeable informant (including information regarding grooming disorders). For subjects who had received psychiatric treatment, we obtained relevant medical records and contacted treatment providers, if necessary. Examiners completed a narrative formulation for each case. Inter-rater reliability using these methods was in the “good” to “excellent” range [Bienvenu et al., 2000; Samuels et al., 2006].

Diagnosticians made diagnoses using DSM-IV criteria (or, in the case of PNB and PSP, DSM-IV-like criteria). If all criteria for a given disorder were clearly present, diagnosticians assigned a “definite” diagnosis. If any necessary criterion was clearly not met, then diagnosticians considered the disorder “absent.” If diagnosticians were uncertain about a necessary criterion, but the majority of necessary criteria were present, then the diagnosis could be made at a “probable” level. If diagnosticians were not confident regarding the presence or absence of a given diagnosis, they recorded it as “unknown.” For the purposes of this study, participants with “probable” or “definite” disorders were considered “affected” for the diagnoses in question; this was an a priori decision. Our concern was that some diagnostic criteria for trichotillomania (and, by extension, other grooming disorders) are either difficult to assess accurately or seem to lack validity; for example, some patients with crippling hair-pulling do not clearly endorse tension when pulling out hair or attempting to resist, and some do not clearly endorse pleasure, gratification, or relief upon hair-pulling [Chamberlain et al., 2007].

Diagnostic Consensus Procedure

At each site, two expert diagnosticians independently reviewed all case materials, completed a Diagnostic Assignment Checklist form [Nestadt et al., 2000b], and met to resolve any disagreements regarding diagnoses or age of onset (within 2 years). One of five JHU consensus diagnosticians also reviewed materials from the other sites. We resolved any disagreements between JHU and the other sites before we edited the case materials and sent them for data entry.

Blood Collection

In most cases, interviewers collected blood samples at the time of the diagnostic interview. In some cases, a subject's physician or local phlebotomy laboratory collected a sample at a later time. We sent blood directly to the NIMH Cell Repository at Rutgers University, where staff created EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines and extracted DNA.

Choosing SNPs and Genotyping the Human Sapap3 Locus

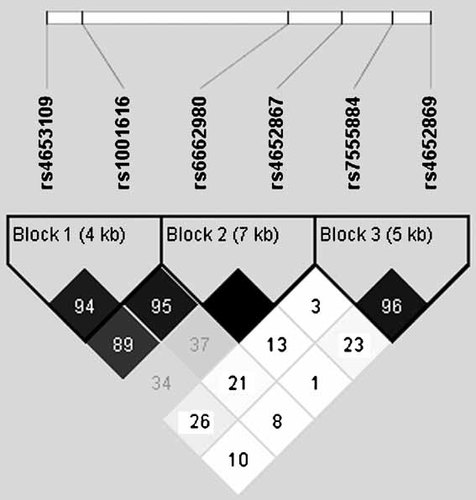

We used public databases (dbSNP Build 126) to select SNPs in the Sapap3 (also denoted Dlgap3) region of chromosome 1p35, to be genotyped by Illumina (San Diego, CA), using their BeadArray system and GoldenGate assay. We gave preference to validated SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.20 and a high Illumina assay anticipated success rate (the actual success rate was >99%). The six SNPs (with MAF >0.20) used in analyses are shown in Figure 1, approximately 1 SNP/8 kb (SNP 1 = rs4653109, SNP 2 = rs1001616, SNP 3 = rs6662980, SNP 4 = rs4652867, SNP 5 = rs7555884, and SNP 6 = rs4652869).

Linkage disequlibrium (D′) map created using Haploview; haplotype blocks created using the confidence interval option. SNP rs4653109 on the 3' end and SNPs rs7555884 and rs4652869 on the 5' end flank the Sapap3 gene, which is transcribed from the negative strand.

In addition to error checking through Illumina, we used PedCheck [O'Connell and Weeks, 1998] and Merlin [Abecasis et al., 2002] to rule out Mendelian inconsistencies and genotypes suggestive of an excessive number of recombinations. We removed genotypes from the dataset if they had posterior probabilities of being incorrect of >75%, as recommended by Douglas et al. (2002).

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics and compared medians using SPSS (version 15) and SAS (version 8). We used Haploview [Barrett et al., 2005] to assess Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. We used the Family-Based Association Test (FBAT) [Horvath et al., 2001] to test individual SNPs and haplotypes for association with GDs and OCD using genotype models and phenotypes from both affected and unaffected individuals. Further, we used the GenAssoc Stata package to estimate genotype relative risks (GRR); this program performs transmission disequlibrium tests for individual loci using data from parent–child trios [Clayton, 2007]. We chose genotype models because these require the fewest assumptions regarding possible modes of genetic transmission.

RESULTS

Descriptive Phenotypic Analyses

Thirty-two percent of the current sample of 1,618 participants met lifetime criteria for a grooming disorder (17%, pathological nail biting or PNB; 20%, pathological skin picking or PSP; 6%, trichotillomania or TT), and 65% met lifetime criteria for OCD. Most of the subjects with GDs had OCD: of those with PNB, 82%; PSP, 87%; TT, 91%; any GD, 84%. Of subjects with OCD, 20% had PNB, 25% had PSP, 8% had TT, and 39% had any GD. Each GD was significantly associated with OCD. The odds ratio (OR) relating PNB and OCD was 2.2 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.6–3.2]; ORPSP,OCD = 3.8 (2.6–5.8); ORTT,OCD = 5.0 (2.4–10); ORGD,OCD = 3.2 (2.4–4.3). Persons with GDs and OCD had significantly earlier ages at onset of OCD symptoms (median 6 years in persons with GD, median 8 without, Mann–Whitney P < 0.0005). GDs were not strongly or specifically related to particular OCD symptom dimensions derived from a factor analysis of Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Symptom Checklist items [Pinto et al., 2008]. Using polychoric correlations, we found that the five OCD symptom dimensions (symmetry/ordering, taboo thoughts, hoarding, doubt/checking, and contamination/ cleaning) related more strongly to each other than to grooming disorders (Table I).

| Taboo thoughts | Symmetry/ordering | Hoarding | Contamination/cleaning | Doubt/checking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry/ordering | 0.53 | ||||

| Hoarding | 0.34 | 0.50 | |||

| Contamination/cleaning | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.42 | ||

| Doubt/checking | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.59 | |

| Pathological nail biting | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Pathological skin Picking | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.17 |

| Trichotillomania | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

| Grooming disorder | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.13 |

- Taboo thoughts: sexual, aggressive, and religious obsessions.

The individual GDs were significantly comorbid with each other. The odds ratio relating PNB to PSP was 4.0 (95% confidence interval = 3.0–5.5); ORPNB,TT = 2.8 (1.8–4.4); ORPSP,TT = 3.3 (2.1–5.2). Each GD was also associated with female sex: OR♀,PNB = 1.4 (1.1–1.9); OR♀,PSP = 1.6 (1.2–2.0), OR♀,TT = 1.8 (1.1–2.8); overall OR♀,GD = 1.6 (1.3–2.0). As reported previously [Samuels et al., 2006], Caucasians are over-represented in this study (90% in the current sample); race was not associated with any GD. The median age of onset of PNB was 6 years (interquartile range: 5–10); PSP = 12 (7–16); TT = 13 (8–17). GDs were also familial. Using data from ∼350 sibling pairs (almost all affected with OCD), the OR for sib-sib similarity for any GD was 1.7 (1.1–2.6).

MOLECULAR GENETIC ANALYSES

Individual SNPs

One thousand, five hundred ninety participants were included in the association analyses. Table II shows the six SNPs included in our analyses (with their coordinates, locations, and genotype frequencies), numbers of informative families for association tests, and results of these tests for the phenotypes GD (i.e., any GD) and OCD. There was no evidence for Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium for any of the 6 SNPs (P > 0.25). GDs were nominally associated with SNP 3 (P < 0.05 using either FBAT or GRR; relative risk ∼1.6 for participants transmitted a G allele); while OCD was not significantly associated with any SNP.

| SNP | Coord | Loc | Genotype (frequency) | Grooming disorder | Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBAT | GRR | FBAT | GRR | ||||||||||||

| Fam | O | E | P | GRR | 95% CI | Fam | O | E | P | GRR | 95% CI | ||||

| #1: rs4653109 | 35100832 | 3′ flanking region | AA (0.36) | 113 | 55 | 58 | 0.64 | … | … | 181 | 119 | 120 | 0.84 | … | … |

| GA (0.48) | 143 | 92 | 84 | 0.19 | 1.14 | 0.76–1.71 | 238 | 193 | 188 | 0.59 | 1.05 | 0.82–1.36 | |||

| GG (0.16) | 65 | 21 | 27 | 0.14 | 0.67 | 0.32–1.39 | 121 | 63 | 66 | 0.56 | 0.82 | 0.54–1.24 | |||

| #2: rs1001616 | 35105513 | Intron 8 | CC (0.10) | 44 | 14 | 17 | 0.40 | 0.73 | 0.31–1.71 | 92 | 49 | 51 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.51–1.26 |

| GC (0.44) | 131 | 82 | 75 | 0.23 | 1.24 | 0.83–1.87 | 219 | 171 | 174 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.76–1.25 | |||

| GG (0.46) | 112 | 54 | 59 | 0.40 | … | … | 182 | 129 | 124 | 0.56 | … | … | |||

| #3: rs6662980 | 35132665 | Intron 3 | AA (0.46) | 129 | 53 | 65 | 0.04 | … | … | 199 | 125 | 136 | 0.20 | … | … |

| GA (0.45) | 148 | 96 | 86 | 0.15 | 1.56 | 1.05–2.30 | 225 | 190 | 177 | 0.16 | 1.23 | 0.97–1.57 | |||

| GG (0.09) | 53 | 25 | 22 | 0.44 | 1.61 | 0.82–3.17 | 83 | 40 | 42 | 0.66 | 1.08 | 0.68–1.71 | |||

| #4: rs4652867 | 35139877 | Intron 1 | TT (0.08) | 40 | 18 | 16 | 0.42 | 1.18 | 0.55–2.53 | 70 | 41 | 37 | 0.36 | 1.14 | 0.73–1.80 |

| GT (0.37) | 113 | 58 | 65 | 0.20 | 0.79 | 0.51–1.22 | 200 | 147 | 156 | 0.28 | 0.90 | 0.70–1.17 | |||

| GG (0.55) | 99 | 57 | 52 | 0.36 | … | … | 181 | 127 | 122 | 0.52 | … | … | |||

| #5: rs7555884 | 35146465 | 5′ flanking region | TT (0.36) | 116 | 56 | 58 | 0.69 | … | … | 191 | 135 | 128 | 0.39 | … | … |

| GT (0.49) | 145 | 86 | 87 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 0.77–1.74 | 243 | 187 | 198 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.76–1.26 | |||

| GG (0.15) | 75 | 37 | 34 | 0.44 | 1.22 | 0.68–2.22 | 129 | 81 | 77 | 0.59 | 1.12 | 0.78–1.62 | |||

| #6: rs4652869 | 35151521 | 5′ flanking region | TT (0.31) | 103 | 49 | 51 | 0.68 | … | … | 171 | 106 | 110 | 0.62 | … | … |

| GT (0.49) | 140 | 90 | 82 | 0.22 | 1.24 | 0.82–1.89 | 237 | 193 | 187 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 0.78–1.33 | |||

| GG (0.20) | 80 | 29 | 35 | 0.20 | 0.87 | 0.46–1.66 | 142 | 80 | 82 | 0.72 | 0.99 | 0.68–1.44 | |||

- CI, confidence interval; Coord, coordinate; E, expected; Fam, number of informative families; FBAT, family-based association test; GRR, genotype relative risk; Loc, location; O, observed; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; …, reference group (GRR = 1.0).

- Bold indicates P ≤ 0.05.

Table III shows association results for the specific GDs separately. PNB was nominally associated with SNP 1 (P < 0.05 using either FBAT or GRR; relative risk ∼3 for those transmitted an A allele) and evidenced a trend (P < 0.10 using FBAT or GRR) toward association with SNP 3 (over-transmission of the G allele). PSP was nominally associated with SNP 3 (especially using GRR—over-transmission of the G allele) and SNP 4 (FBAT only—under-transmission of the GT genotype). Finally, TT, the least frequent of the GDs, showed the strongest evidence for association to SNP 3 (over-transmission the G allele), as well as some evidence for association with SNP 6 (FBAT only—under-transmission of the GG genotype).

| SNP | Genotype (frequency) | Pathological nail biting | Pathological skin picking | Trichotillomania | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBAT | GRR | FBAT | GRR | FBAT | GRR | ||||||||||||||

| Fam | O | E | P | GRR | 95% CI | Fam | O | E | P | GRR | 95% CI | Fam | O | E | P | GRR | 95% CI | ||

| #1 | AA (0.36) | 62 | 34 | 31 | 0.44 | 3.32 | 1.01–10.9 | 78 | 39 | 38 | 0.85 | … | … | 35 | 12 | 15 | 0.33 | … | … |

| GA (0.48) | 77 | 45 | 42 | 0.51 | 2.95 | 0.99–8.83 | 98 | 57 | 56 | 0.82 | 1.11 | 0.67–1.86 | 42 | 28 | 22 | 0.06 | 1.52 | 0.70–3.30 | |

| GG (0.16) | 34 | 7 | 13 | 0.03 | … | … | 45 | 16 | 18 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.24–1.69 | 18 | 3 | 6 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.08–2.04 | |

| #2 | CC (0.10) | 23 | 6 | 9 | 0.24 | … | … | 33 | 12 | 12 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.27–2.14 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 0.12 | 1.17 | 0.58–2.35 |

| GC (0.44) | 72 | 40 | 40 | 0.94 | 2.63 | 0.73–9.45 | 93 | 54 | 51 | 0.57 | 1.27 | 0.77–2.10 | 42 | 24 | 21 | 0.35 | |||

| GG (0.46) | 61 | 34 | 32 | 0.56 | 3.09 | 0.79–12.0 | 78 | 37 | 39 | 0.62 | … | … | 39 | 17 | 18 | 0.80 | … | … | |

| #3 | AA (0.46) | 71 | 26 | 34 | 0.06 | … | … | 93 | 37 | 46 | 0.06 | … | … | 39 | 11 | 18 | 0.03 | … | … |

| GA (0.45) | 83 | 51 | 46 | 0.31 | 1.62 | 0.94–2.80 | 106 | 68 | 60 | 0.16 | 1.81 | 1.10–2.98 | 42 | 31 | 23 | 0.01 | 2.44 | 1.09–5.48 | |

| GG (0.09) | 30 | 16 | 13 | 0.24 | 2.27 | 0.91–5.66 | 35 | 16 | 14 | 0.54 | 1.56 | 0.63–3.87 | 14 | 3 | 5 | 0.32 | |||

| #4 | TT (0.08) | 20 | 6 | 6 | 0.85 | 1.18 | 0.39–3.61 | 26 | 15 | 11 | 0.16 | 1.33 | 0.52–3.42 | 7 | — | — | — | 0.58 | 0.27–1.24 |

| GT (0.37) | 59 | 33 | 31 | 0.64 | 1.04 | 0.55–1.98 | 82 | 34 | 46 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 0.39–1.17 | 37 | 14 | 19 | 0.12 | |||

| GG (0.55) | 54 | 24 | 25 | 0.69 | … | … | 71 | 46 | 38 | 0.05 | … | … | 35 | 22 | 17 | 0.08 | … | … | |

| #5 | TT (0.36) | 66 | 28 | 31 | 0.51 | … | … | 87 | 44 | 43 | 0.87 | … | … | 35 | 10 | 15 | 0.08 | … | … |

| GT (0.49) | 82 | 47 | 47 | 0.98 | 1.53 | 0.85–2.76 | 105 | 56 | 60 | 0.47 | 1.22 | 0.74–2.00 | 48 | 29 | 25 | 0.22 | 1.30 | 0.56–3.00 | |

| GG (0.15) | 43 | 21 | 18 | 0.44 | 1.65 | 0.72–3.79 | 53 | 25 | 22 | 0.39 | 1.36 | 0.66–2.81 | 26 | 12 | 11 | 0.78 | 1.26 | 0.40–3.96 | |

| #6 | TT (0.31) | 55 | 23 | 25 | 0.58 | … | … | 72 | 32 | 34 | 0.57 | … | … | 34 | 16 | 16 | 0.98 | … | … |

| GT (0.49) | 77 | 47 | 44 | 0.48 | 1.29 | 0.70–2.36 | 103 | 64 | 57 | 0.22 | 1.25 | 0.74–2.11 | 42 | 26 | 22 | 0.20 | 1.14 | 0.54–2.43 | |

| GG (0.20) | 43 | 18 | 19 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.34–2.03 | 62 | 24 | 28 | 0.28 | 0.75 | 0.34–1.65 | 20 | 4 | 8 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.19–2.86 | |

- CI, confidence interval; E, expected; Fam, number of informative families; FBAT, family-based association test; GRR, genotype relative risk; O, observed; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; …, reference group (GRR = 1.0).

- Bold indicates P ≤ 0.05.

Haplotypes

As illustrated in Figure 1, three biallelic haplotype blocks were evident using the confidence interval option [Gabriel et al., 2002] in Haploview [Barrett et al., 2005]. Tables IV and V show haplotype association results for the five related phenotypes of interest. In these analyses, the permutation function of FBAT was available to calculate empirical P-values (performed using 10,000 replicates). Results were largely as expected given the individual SNP associations evident in Tables II and III (e.g., over-transmission of the G allele at SNP 3 in participants with GDs).

| Haplotype block | Model | Haplotype (frequency) | Grooming Disorder | OCD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fam | O | E | P* | Fam | O | E | P* | |||

| #1 rs4653109–rs1001616 | Additive | A-G (0.62) | 138 | 249 | 245 | 0.63 | 194 | 371 | 370 | 0.62 |

| G-C (0.28) | 127 | 122 | 119 | 0.75 | 184 | 231 | 233 | 0.75 | ||

| G-G (0.09) | 58 | 36 | 42 | 0.24 | 79 | 76 | 71 | 0.81 | ||

| A-C (0.01) | 10 | 5 | 6 | 1.00 | 15 | 12 | 15 | 0.28 | ||

| Dominant | A-G (0.62) | 63 | 174 | 170 | 0.42 | 116 | 432 | 428 | 0.49 | |

| G-C (0.28) | 110 | 106 | 101 | 0.52 | 177 | 281 | 280 | 0.89 | ||

| G-G (0.09) | 57 | 35 | 40 | 0.31 | 92 | 106 | 104 | 0.75 | ||

| A-C (0.01) | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0.88 | 16 | 16 | 19 | 0.20 | ||

| Recessive | A-G (0.62) | 96 | 75 | 74 | 0.89 | 154 | 172 | 171 | 0.83 | |

| G-C (0.28) | 30 | 16 | 18 | 0.54 | 71 | 60 | 64 | 0.41 | ||

| #2 rs6662980–rs4652867 | Additive | A-G (0.44) | 154 | 187 | 200 | 0.09 | 199 | 340 | 342 | 0.42 |

| G-G (0.30) | 144 | 183 | 167 | 0.03 | 174 | 236 | 237 | 0.30 | ||

| A-T (0.26) | 110 | 128 | 131 | 0.57 | 153 | 198 | 195 | 0.87 | ||

| Dominant | A-G (0.44) | 112 | 153 | 160 | 0.26 | 177 | 403 | 410 | 0.38 | |

| G-G (0.30) | 125 | 152 | 140 | 0.05 | 193 | 339 | 328 | 0.16 | ||

| A-T (0.26) | 95 | 106 | 111 | 0.27 | 173 | 265 | 270 | 0.55 | ||

| Recessive | A-G (0.44) | 79 | 34 | 40 | 0.16 | 138 | 113 | 115 | 0.70 | |

| G-G (0.30) | 45 | 31 | 27 | 0.23 | 70 | 63 | 64 | 0.88 | ||

| A-T (0.26) | 35 | 22 | 20 | 0.47 | 59 | 51 | 48 | 0.48 | ||

| #3 rs7555884–rs4652869 | Additive | T-G (0.44) | 147 | 186 | 190 | 0.60 | 192 | 299 | 293 | 0.90 |

| G-T (0.39) | 149 | 193 | 188 | 0.56 | 190 | 294 | 299 | 0.86 | ||

| T-T (0.16) | 98 | 90 | 91 | 0.77 | 114 | 141 | 140 | 0.87 | ||

| Dominant | T-G (0.44) | 109 | 150 | 150 | 0.97 | 170 | 366 | 364 | 0.72 | |

| G-T (0.39) | 122 | 152 | 148 | 0.47 | 188 | 366 | 369 | 0.74 | ||

| T-T (0.16) | 92 | 82 | 83 | 0.77 | 134 | 205 | 205 | 0.96 | ||

| Recessive | T-G (0.44) | 68 | 36 | 40 | 0.32 | 119 | 106 | 107 | 0.86 | |

| G-T (0.39) | 63 | 41 | 40 | 0.72 | 106 | 105 | 104 | 0.93 | ||

| T-T (0.16) | 18 | 8 | 8 | 0.93 | 29 | 21 | 20 | 0.73 | ||

- E, expected; Fam, number of informative families; O, observed; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Bold indicates P ≤ 0.05.

- * Permuted P-value, calculated using Monte Carlo samples from the null distribution (10,000 replicates).

| Haplotype block | Model | Haplotype (frequency) | PNB | PSP | TT | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fam | O | E | P* | Fam | O | E | P* | Fam | O | E | P* | |||

| #1 rs4653109–rs1001616 | Additive | A-G (0.62) | 75 | 135 | 125 | 0.05 | 98 | 167 | 163 | 0.57 | 39 | 60 | 60 | 0.95 |

| G-C (0.28) | 70 | 58 | 62 | 0.30 | 93 | 86 | 84 | 0.77 | 40 | 26 | 28 | 0.58 | ||

| G-G (0.09) | 31 | 16 | 21 | 0.15 | 37 | 20 | 25 | 0.14 | 16 | 11 | 10 | 0.49 | ||

| Dominant | A-G (0.62) | 31 | 92 | 87 | 0.05 | 46 | 115 | 114 | 0.98 | 16 | 45 | 42 | 0.15 | |

| G-C (0.28) | 60 | 50 | 52 | 0.47 | 78 | 73 | 70 | 0.58 | 37 | 25 | 25 | 0.97 | ||

| G-G (0.09) | 30 | 15 | 19 | 0.20 | 37 | 20 | 24 | 0.19 | 16 | 11 | 10 | 0.44 | ||

| Recessive | A-G (0.62) | 54 | 43 | 38 | 0.24 | 68 | 52 | 49 | 0.47 | 28 | 15 | 17 | 0.46 | |

| G-C (0.28) | 16 | 8 | 10 | 0.31 | 26 | 13 | 14 | 0.72 | 7 | — | — | — | ||

| #2 rs6662980-rs4652867 | Additive | A-G (0.44) | 92 | 92 | 104 | 0.04 | 104 | 131 | 137 | 0.34 | 42 | 49 | 49 | 0.97 |

| G-G (0.30) | 83 | 102 | 90 | 0.03 | 103 | 122 | 110 | 0.06 | 40 | 41 | 36 | 0.13 | ||

| A-T (0.26) | 54 | 58 | 57 | 0.92 | 81 | 85 | 90 | 0.28 | 37 | 22 | 27 | 0.12 | ||

| Dominant | A-G (0.44) | 66 | 73 | 82 | 0.06 | 72 | 109 | 109 | 0.99 | 32 | 42 | 39 | 0.36 | |

| G-G (0.30) | 70 | 83 | 75 | 0.09 | 90 | 101 | 91 | 0.05 | 37 | 38 | 32 | 0.02 | ||

| A-T (0.26) | 49 | 50 | 49 | 0.92 | 69 | 67 | 75 | 0.04 | 35 | 20 | 25 | 0.13 | ||

| Recessive | A-G (0.44) | 49 | 19 | 23 | 0.28 | 53 | 22 | 28 | 0.12 | 23 | 7 | 10 | 0.28 | |

| G-G (0.30) | 26 | 19 | 15 | 0.14 | 30 | 21 | 19 | 0.49 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 0.39 | ||

| A-T (0.26) | 15 | 8 | 8 | 0.98 | 24 | 18 | 15 | 0.29 | 7 | — | — | — | ||

| #3 rs7555884-rs4652869 | Additive | T-G (0.44) | 81 | 103 | 102 | 0.80 | 109 | 127 | 130 | 0.62 | 45 | 40 | 44 | 0.25 |

| G-T (0.39) | 83 | 108 | 102 | 0.31 | 108 | 119 | 118 | 0.86 | 49 | 57 | 51 | 0.19 | ||

| T-T (0.16) | 54 | 38 | 45 | 0.10 | 68 | 59 | 58 | 0.92 | 23 | 17 | 18 | 0.65 | ||

| Dominant | T-G (0.44) | 60 | 82 | 80 | 0.54 | 77 | 100 | 101 | 0.84 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 0.93 | |

| G-T (0.39) | 68 | 84 | 80 | 0.32 | 91 | 93 | 92 | 0.86 | 35 | 43 | 38 | 0.09 | ||

| T-T (0.16) | 53 | 37 | 42 | 0.17 | 64 | 53 | 54 | 0.88 | 19 | 15 | 16 | 0.76 | ||

| Recessive | T-G (0.44) | 40 | 21 | 22 | 0.74 | 52 | 27 | 29 | 0.59 | 19 | 5 | 9 | 0.04 | |

| G-T (0.39) | 37 | 24 | 22 | 0.60 | 45 | 26 | 26 | 0.99 | 23 | 14 | 13 | 0.72 | ||

| T-T (0.16) | 7 | — | — | — | 10 | 6 | 5 | 0.36 | 6 | — | — | — | ||

- E, expected; Fam, number of informative families; O, observed; PNB, pathological nail biting; PSP, pathological skin picking; TT, trichotillomania.

- Bold indicates P ≤ 0.05.

- * Permuted P-value, calculated using Monte Carlo samples from the null distribution (10,000 replicates).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first association study of Sapap3 variants and psychiatric phenomena in humans. In this report, we provide preliminary evidence that variation in the Sapap3 gene is associated with human grooming disorders, which appear familial and substantially comorbid with each other and with OCD. Variation in Sapap3 did not appear associated with OCD itself in our analyses; however, it is important to bear in mind that GDs without OCD were uncommon in this sample, which includes families selected to be informative for OCD genetic studies.

Given the prominence of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the “OCD circuit” [Graybiel and Rauch, 2000; Saxena and Rauch, 2000; Aouizerate et al., 2004; Swedo and Snider, 2004], glutamate has been receiving increasing attention in the OCD literature [Rosenberg et al., 2000; Chakrabarty et al., 2005; Coric et al., 2005; Pittenger et al., 2006]. At least two other genes affecting glutamatergic neurotransmission appear associated with OCD, SLC1A1 [Arnold et al., 2006; Dickel et al., 2006; Stewart et al., 2007] and, more preliminarily, GRIN2B [Arnold et al., 2004]. Again, we found no evidence for an association of Sapap3 with OCD itself, though we cannot rule out the possibility that Sapap3 is relevant to a pathological grooming-related “subtype” of OCD (recall that more than 1/3 of the participants with OCD had a GD). Also, it is possible that other SAPAP genes are relevant to OCD and related conditions (unexplored in the current study).

We have no reason to believe that any of the SNPs examined in this report might be causal variants. In this preliminary study, we limited our analyses to SNPs with relatively high MAFs in order to cover the region for association tests with what appeared, a priori, to be promising phenotypes—some of which were relatively uncommon in this sample (especially TT). In the future, we plan to examine the Sapap3 region more thoroughly, using less highly variant known SNPs, as well as new SNPs identified through sequencing and the HapMap project. Notably, Zuchner et al. (personal communication) have recently sequenced Sapap3 exons in patients with OCD and/or TT and controls. They identified multiple rare missense variants in patients with OCD and/or TT; such variants were significantly more frequent in patients than controls. Our results, and the results of Zuchner et al., suggest that this gene is worthy of additional study in humans.

Notably, while human OCD has fairly well-defined neuroanatomical correlates, the same cannot be said, at this point, for GDs. That is, though our study builds upon the basic science work of Welch et al. (2007), which strongly implicates the striatum in Sapap3-related pathological grooming in mice, it remains to be demonstrated which particular brain regions are involved in human GDs. Neuroimaging results for TT (the only GD studied with this method, to our knowledge) are somewhat mixed [Chamberlain et al., 2007]. Though some studies have implicated the striatum in TT [O'Sullivan et al., 1997; Stein et al., 2002; Chamberlain et al., 2008], others have not [Swedo et al., 1991; Rauch et al., 2007]. Also, though Sapap3 is highly expressed in the striatum [Kindler et al., 2004; Welch et al., 2004], it is also expressed in other brain regions like the cerebellum, which has also been implicated in neuroimaging studies of TT [Swedo et al., 1991; Keuthen et al., 2007].

Also, GDs tend to be comorbid with several anxiety and mood disorders besides OCD [Cullen et al., 2001; Chamberlain et al., 2007]. In a previous latent class analysis of 14 diagnoses among participants in the Johns Hopkins OCD Family Study [Nestadt et al., 2003], we found that GDs were most prevalent in a “highly comorbid” class, which was characterized by particularly high prevalences of OCD, recurrent major depression, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and somatoform disorders (hypochondriasis and body dysmorphic disorder), and was associated with high neuroticism [tic disorders had a low prevalence in this class, though, as in the current study, probands with Tourette's disorder were excluded]. Our previous finding of an OCD subtype that is highly comorbid with grooming disorders, GAD, and anxiety-related personality traits is remarkable in that anxiety-like behaviors were phenotypically prominent in Sapap3 mutant mice [Welch et al., 2007]. Thus, other human phenotypes may be worth examining in relation to this gene.

Finally, though our genotypic effect sizes were fairly large for GDs (relative risks = 1.6–3.3), evidence for statistical significance was limited, especially if one takes a strict view of the need to correct for multiple tests (in this case, six related SNPs in or near the Sapap3 gene, as well as more than one related phenotype). Thus, it is important to attempt to replicate our findings in other samples (e.g., in samples of patients with GDs). Nevertheless, the current findings are encouraging, in light of the basic science research findings upon which they build [Welch et al., 2007] and the recent sequencing study mentioned above (Zuchner et al., personal communication). That is, though one is always making a bit of a “leap” when moving from animal models to humans, the basic science and sequencing findings suggest a greater than zero prior probability of an association between Sapap3 variants and human GDs; thus, a strict correction for multiple tests would seem excessive at this early stage of research.

Acknowledgements

NIH grants MH50125, RR00052, NS42609, MH64543, and MH66284 supported this study. The authors thank the many families who have participated in the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study (OCGS); the Obsessive-Compulsive Foundation; Ann Pulver, PhD, Kathleen Merikangas, PhD, David Houseman, MD, and Alec Wilson, PhD, for consultation; and clinicians and coordinators at each OCGS site: Providence (Maria Mancebo, PhD, Richard Marsland, RN, and Shirley Yen, PhD); New York (Renee Goodwin, PhD, Joshua Lipsitz, PhD, and Jessica Page, PsyD); Baltimore (Laura Eisen, BS, Karan Lamb, PsyD, Tracey Lichner, PhD, Yung-mei Leong, PhD, and Krista Vermillion, BA); Boston (Dan Geller, MD, Anne Chosak, PhD, Michelle Wedig, BS, Evelyn Stewart, MD, Michael Jenike, MD, Beth Gershuny, PhD, and Sabine Wilhelm, PhD); Bethesda (Lucy Justement, Diane Kazuba, V. Holland LaSalle-Ricci, and Theresa B. DeGuzman); and Los Angeles (R. Lindsey Bergman, PhD, Susanna Chang, PhD, Audra Langley, PhD, and Amanda Pearlman, BA).