Are SCN2A-related BFNISs also responsible for seizures in adulthood? A case report opens new scenarios

Abstract

Large cohort studies and variant-specific electrophysiology have enabled the delineation of different SCN2A-epilepsy phenotypes, phenotype–genotype correlations, prediction of pharmacosensitivity to sodium channel blockers, and long-term prognostication for clinicians and families. One of the most common clinical presentations of SCN2A pathological variants is benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures (BFNIS), which are characterized by seizure onset between the first day of life and 23 months of age and typically resolve, either spontaneously or with the aid of sodium channel blockers, within the first 2 years of life. In 2004, Berkovic et al. reported the case of a young boy affected by SCN2A-related BFNIS whose mother, who carried the same pathological variant, had also presented with BFNIS in infancy. Our case report focuses on the aforementioned woman who, more than 40 years later, presented two additional seizures, therefore opening the possibility of a role for SCN2A-related seizures in adulthood.

1 INTRODUCTION

The sodium channel voltage-gated type II alpha (SCN2A) gene encodes the alpha subunit of the neuronal voltage-gated type II sodium channel (Nav1.2). Pathogenic variants of this gene cause a variety of neurodevelopmental syndromes of variable severity ranging from self-limiting epilepsy (febrile seizures and benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures—BFNIS) to developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEEs). Other possible clinical expressions of SCN2A variants include movement disorders like chorea and episodic ataxia, but also autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability with and without seizures (Reynolds et al., 2020). To date, 276 subjects with SCN2A variants and epilepsy have been published in the literature (Mangano et al., 2022).

From a clinical point of view, phenotypic presentations of SCN2A pathological variants may be divided into three major groups: BFNIS, DEE, and intellectual disability and/or autism with possible late-onset seizures (Wolff et al., 2019).

The first phenotype described in SCN2A-related disorders was BFNIS (Heron et al., 2002), which accounts for approximately 20% of the phenotypic spectrum. Age at seizure onset is from the first day of life to 23 months (typically in the first month), and predominant seizure types include focal clonic, tonic, and generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Interictal EEG often shows a normal background activity with focal or multifocal spikes and might be completely normal in some cases (Wolff et al., 2019). BFNIS are easily controlled by antiseizure medication, in particular, sodium-channel blockers (SCBs), or cease spontaneously (Berkovic et al., 2004). Cognitive development remains normal, while a subset of children may develop episodic ataxia in infancy or childhood (Liao, Anttonen, et al., 2010).

DEE represents the most frequent clinical presentation of SCN2A-related disorders, accounting for 60%–70% of published cases. Approximately two thirds of children with DEE have epilepsy onset within the first 3 months of life (neonatal and early infantile DEE) (Wolff et al., 2017). These patients may present with Ohtahara syndrome or, less frequently, with epilepsy with migrating focal seizures, as well as DEE without specific syndromic features other than drug-resistant asymmetrical tonic seizures with clonic components and severely abnormal wake and sleep EEG. The remaining one third of SCN2A-DEE patients have epilepsy onset beyond the early infantile period (infantile and childhood DEE) (Wolff et al., 2019). The most important specific epileptic phenotype in this subgroup is Infantile Spasm Syndrome (previously referred to as West syndrome).

Finally, at least 16% of SCN2A patients are affected by intellectual disability and/or autism spectrum disorder (Wolff et al., 2017).

In 2017, Wolff et al. analyzed the SCN2A pathological variants underlying the different phenotypical presentations. The study revealed the presence of gain of function (GoF) mutations in patients presenting with early onset epilepsy (<3 months), both in the case of early DEEs and of BFNISs. In contrast, they found clear loss-of-function (LoF) effects for mutations in children with later onset infantile/childhood epilepsy, as well as autism spectrum disorder without epilepsy. The correlation between early onset and later onset of seizures in relation to GoF and LoF mutations might be due to the different expression of the Nav1.2 channel during brain development. In particular, in the early stages of development, this channel is highly expressed at nodes of Ranvier and axon initial segments, so GoF mutations can cause neuronal hyperexcitability and seizures. Later, during development, the Nav1.2 channel is partially replaced by the Nav1.6 channel, therefore, seizures are typically limited to the infantile period (Liao, Deprez, et al., 2010). However, the Nav1.2 channel is still expressed in unmyelinated fibers, such as those from cortical inhibitory neurons. This means that LoF mutations (which do not cause seizures in the early infantile period) can cause reduced excitability of these inhibitory neurons and, therefore, lead to hyperexcitability and seizures later in development.

This distinction between the underlying genetic mechanism may also explain why early-onset seizures (such as BFNIS) caused by GoF mutations show a good response to SCBs, while later-onset seizures (such as in childhood DEEs or autism with late-onset epilepsy) caused by LoF mutations are worsened by the use of SCBs (Wolff et al., 2017).

2 CASE REPORT

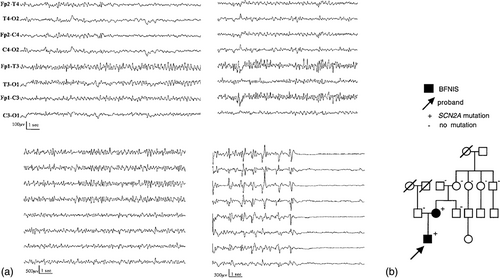

In 2004, Berkovic et al. tried to identify the correlation between the molecular and clinical phenotype of SCN2A pathological variants in early childhood epilepsy within six families (Berkovic et al., 2004). One of these families, indicated in the study as “Family E,” was referred to our Regional Epilepsy Center Brescia (Italy) because of a 3-month-old infant who presented with epileptic seizures characterized by clonic jerking of both eyelids and mouth on the right side, staring, perioral cyanosis, tonic contraction of the lower limbs, and generalized twitching. EEG findings identified an ictal onset in the left temporal region with bilateral diffusion (Figure 1).

The boy was treated with phenobarbital and stopped having seizures 2 months later, at 5 months of age.

Examining the family's medical history, the authors discovered that the proband's mother had suffered from epileptic seizures from 5 months to 1 year of age, which were characterized by generalized hypertonus and perioral cyanosis.

The family underwent genetic examination, which revealed a R1319Q gain-of-function mutation in the SCN2A gene of both the affected individuals, a pathogenic variant which can be found both in BFNISs and DEEs (Zeng et al., 2022). The variant was not present in the maternal grandparents (who indeed denied the presence of seizures in their medical history), suggesting a de novo mutation in the mother.

In March 2020, 44 years after presenting with BFNIS, the proband's mother presented two additional epileptic seizures. The woman suffered a first episode at home (in a condition of physical well-being, in the absence of sleep deprivation or substance intoxication); she reported general malaise, nausea, sialorrhea, and rapid loss of consciousness, followed a few minutes later by slow recovery and confusion. She was therefore brought to the ER, where, approximately half an hour later, she suffered a second seizure characterized by oculocephalic deviation to the left and abduction and hyperextension of the left upper limb, clonic jerking of the lower limbs and loss of consciousness. The episode lasted 3 min and was followed by a slow recovery of awareness, post-ictal confusion, and amnesia.

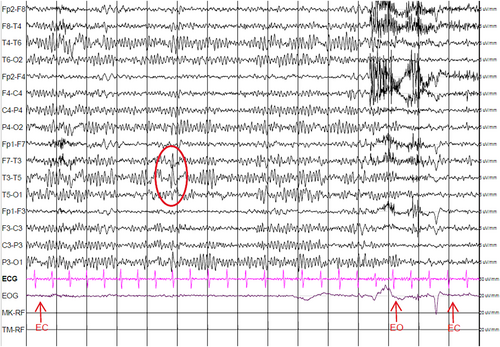

The following day, the woman underwent an awake EEG, which detected spikes and sharp waves in the left temporal leads (Figure 2). To exclude a lesional etiology, a brain MRI was performed, which resulted in a negative. The patient also underwent cardiologic examination (including cardiac ultrasound and 24 h Holter), which excluded a cardiac etiology.

She was, therefore, started on lamotrigine, a sodium-channel blocker that is frequently used as an antifocal medication in adults.

Since then, she performed annual EEG recordings showing temporal abnormalities in the left hemisphere. After 3 years of follow-up on lamotrigine, she continues to be seizure-free.

3 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

So far, the scientific literature does not describe patients with a history of BFNIS who present with additional epileptic seizures in adulthood, in the absence of an underlying lesion or encephalopathy.

Nonetheless, the similarities in the focal origin of the seizures, which in both the mother and the son seem to originate from the left temporal regions, alongside the underlying genetic variant and the negativity of the brain MRI, suggest that in some cases, SCN2A pathological variants might not determine a self-limited epilepsy but rather an age-dependent epilepsy that gives rise to seizures in the neonatal period but may also lead to seizures in adulthood.

We cannot state that the SCN2A pathological variant is certainly responsible for the epileptic seizures presented by our adult subject, however, this possibility cannot be ruled out. We, therefore, suggest a potential role for SCN2A genetic testing in adults presenting with seizures and a history of BFNIS.

To our knowledge, this is the first case reported in the literature in which a mutation of SCN2A is hypothesized to determine the re-occurrence of seizures in adulthood.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sara Brunetti: Writing – Original draft preparation. Alice Muda: Writing – Original draft preparation; Writing – Review and editing. Chiara Conti: Writing – Original draft preparation. Stefano Gazzina: Critical review; Commentary and revision. Patrizia Accorsi: Supervision. Lucio Giordano: Conceptualization and supervision.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.