Anxiety in Wiedemann–Steiner syndrome

Funding information: Wiedemann–Steiner Syndrome Foundation; The Hartwell Foundation; National Institute of Child Health and Development, Grant/Award Number: K08HD086250; National Institute of Child Health and Development, Grant/Award Number: K23HD101646

Abstract

This study examined anxiety in Wiedemann–Steiner syndrome (WSS). Eighteen caregivers and participants with WSS completed the parent- and self-report versions of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorder or the adapted version of the Screen for Adult Anxiety Related Disorder. Approximately 33.33% of parents and 65% of participants with WSS rated in the clinical range for overall anxiety. Across anxiety subtypes, parents primarily indicated concerns with Separation Anxiety (72%), which was also endorsed by the majority of participants with WSS (82%). The emergent trend showed Total Anxiety increased with age based on parent-informant ratings. The behavioral phenotype of WSS includes elevated anxiety. Clinical management should include incorporating early behavioral interventions to bolster emotion regulation given the observed risk of anxiety with age.

1 INTRODUCTION

Wiedemann–Steiner syndrome (WSS, MIM 605130) is a Mendelian disorder of epigenetic machinery (MDEM), a group of disorders with mutations in genes that encode epigenetic regulators, including proteins involved in writing, erasing, and reading of chromatin marks and chromatin remodeling (Fahrner & Bjornsson, 2014; Fahrner & Bjornsson, 2019). Specifically, WSS is caused by a heterozygous pathogenic variant in the KMT2A gene (Jones et al., 2012), which results in a defect in the methylation of H3 lysine K4 (H3K4) in early development and dysregulated gene expression. Cardinal features of WSS include hypertrichosis, growth deficiency, and intellectual disability or developmental delay (Aggarwal et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2012; Miyake et al., 2016; Sheppard et al., 2021).

At present, the behavioral phenotype in WSS is relatively unknown given limited prospective investigations with affected individuals. To date, most of the published literature involving those with WSS consists of clinical case studies or retrospective review of patients' medical records, thus, reported findings on behavioral patterns (e.g., psychopathology, psychosocial adjustment, adaptive skills, etc.) are typically comprised of mixed measures or diagnostic approaches. Systematic research directed toward characterizing the neurobehavioral phenotype associated with WSS is imperative to identify outcome targets as part of designing clinical treatment trials. Notably, emergent clinical investigations on epigenetic interventions with MDEMs such as Kabuki syndrome implicate plasticity in postnatal development (Benjamin et al., 2017; Bjornsson et al., 2014), underlining the promise of the novel therapeutic approaches on functional recovery.

To address the gap in literature, this study focused on examining risk for anxiety among youth and adults with WSS by use of parent- and self-informant versions of a common screening inventory—the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorder (SCARED) or the adapted version of the Screen for Adult Anxiety Related Disorder (SCAARED). Given prior research with animal models showed KMT2A-deficient mice demonstrate increased anxiety (Shen et al., 2014) and our anecdotal clinical experience, we anticipated a sizeable proportion of participants with WSS will be rated in the clinical range for anxiety based on caregiver and self-informant responses. However, no specific prediction was made regarding the anxiety type (Panic Separation Anxiety Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder) that may be more prevalent than others; or between the level of symptomatology as a function of informant type (parent- vs. self-ratings).

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

A total of 18 caregivers of individuals with WSS (7F, Mage = 15.61 years, SD = 7.84, range = 8–33) participated in this study, which required the completion of a research intake questionnaire and a parent-report version of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorder (SCARED) or the adapted version of the Screen for Adult Anxiety Related Disorder (SCAARED). Of these, 17 individuals with WSS completed the self-report version of the SCARED or SCAARED (7F, Mage = 15.79 years, SD = 8.05, range = 8–33). All participants reported English proficiency and White ethnic background. This sample was recruited through international patient advocacy groups as part of a large remote survey study. Participants and caregivers received the SCARED or SCAARED electronically to complete.

All caregivers except one shared genetic test records. One parent provided information on the type of testing completed and the variant of KMT2A found but declined to share a copy of the actual medical report. The authors reviewed these records to confirm the WSS diagnosis. The diagnosis was made in the majority of our sample through whole exome sequencing (77.77%) (N = 14). Two participants were diagnosed via single gene sequencing, one with a nonspecific intellectual disability panel, and one who completed a genetic research panel. Most participants had de novo variants (77.77%) (N = 14), two were inherited from a parent with proven mosaicism, and two had unknown inheritance. All participants had a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant. Participants with additional genetic variants that affected neurodevelopment or behavior were excluded to allow more precise analysis of the association between observed neurobehavioral patterns and WSS. All respondents are English proficient based on caregiver report and reside in the United States with the exception of three (one from Australia, the Netherlands, and Canada). Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at authors' affiliated institutes and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent and/or assent were obtained by patient's legal guardian and/or the patient prior to inclusion in the study.

2.2 Procedure and materials

All participating caregivers and individuals with WSS were sent the following inventories via email to complete remotely. Caregivers completed an intake questionnaire that included a question regarding a history of anxiety disorder diagnosis, behavior intervention or psychotherapy, and psychotropic medication treatment to address anxiety/mood or behavioral problems.

These parents also completed the caregiver-informant version of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorder (SCARED) (Birmaher et al., 1997) or the adapted version of the Screen for Adult Anxiety Related Disorder (SCAARED) (Angulo et al., 2017), screening tools commonly used to index anxiety in children and adults respectively. The SCARED is an inventory suitable for children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years of age, and consists of 41 items that yield six factors: Panic Disorder or significant Somatic Symptoms, Separation Anxiety Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, and School Avoidance. Of note, Panic Disorder is a condition characterized by a rapid onset of physiological symptoms of distress (e.g., rating heart, sweating, tremors, nausea, etc.), Separation Anxiety is marked by worries when separated from caregivers or family or thoughts about separation, and Social Anxiety Disorder is defined by distress when socializing with others, self-consciousness and fear of embarrassment/ridicule. In contrast, Generalized Anxiety Disorder is a psychological disorder whereby tension and anxieties for common daily events are exaggerated and difficult to control. Importantly, School Avoidance is not a clinical disorder but refers to school refusal and somatic complaints associated with anxieties with school.

The SCAARED is comprised of 44 items that yield the same factors except for School Avoidance; and was developed for those age 18 years and older. Both measures require the respondent to rate items on a three point Likert scale (Not true or Hardly ever true, Somewhat true or Sometimes true, Very true or Always true), and provide a Total Anxiety composite. Given high rate of intellectual disability associated with WSS and concerns regarding adequate comprehension or reading skills to complete the self-report measures, parents were instructed to read items aloud to their children if needed, and reminded to avoid providing additional prompting or querying. Total ratings across anxiety domains (Panic Disorder or significant Somatic Symptoms, Separation Anxiety Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, School Avoidance) and overall anxiety (Total Anxiety) were determined clinically significant based on previously published clinical cut-offs (Angulo et al., 2017; Birmaher et al., 1997). A total of 15 caregivers of children with WSS and 3 adults with the syndrome participated in this study. All but one child with WSS completed the self-report version of the inventory. On the SCARED, raw scale scores at or above 7 in Panic Disorder or Somatic Symptoms, 9 in Generalized Anxiety Disorder, 5 in Separation Anxiety, 8 in Social Anxiety, and 25 in Total Anxiety are considered clinically significant. On the SCAARED, clinical level is determined when raw scale scores meet or exceed 5 in Panic Disorder or Somatic Symptoms, 12 in Generalized Anxiety Disorder, 3 in Separation Anxiety, 7 in Social Anxiety, and 23 in Total Anxiety.

Prior research on the psychometric properties of SCARED report sensitivity of 0.70 and a specificity of 0.50 in typically developing population (Birmaher et al., 1997), and similarly, sensitivity of 0.78 and specificity of 0.52 respectively among those with autism spectrum disorder (Stern et al., 2014). This inventory has also demonstrated strong discriminant validity between types of anxiety disorders in typically developing samples (Birmaher et al., 1999). A recent meta-analytic investigation reported moderate to large parent–child agreement rates, and good internal consistency across all factors in the child and parent informant forms, except for School Avoidance (Runyon et al., 2018). Likewise, the SCAARED has been documented to yield good internal consistency and discriminant validity (Angulo et al., 2017), although, to our knowledge, the measure has not been published among those with neurodevelopmental disorders.

2.3 Data strategy

Descriptive analyses were used to examine frequency of participants with a prior diagnosis of anxiety disorder and history of behavioral therapy; to review mean ratings across domains of the SCARED/SCAARED parent- and self-informant inventories; and to assess the percentage of participants that exceed clinical classification cut-off across anxiety subtypes based on parent- and self-report SCARED/SCAARED. Friedman test was applied to assess differences in self- vs. parent-ratings across anxiety types (Panic Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Separation Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety) and overall anxiety (Total Anxiety) in the whole sample and the subgroup of children/adolescent participants who completed the SCARED. This test was not utilized for the adult sample given the low number of participants. McNemar's test was also used to examine differences in participants that met clinical cut-off for Total Anxiety based on parent- vs. self-ratings on the SCARED/SCAARED between the whole sample and the subgroup of children/adolescents with WSS.

Subsequently, inter-rater agreement was assessed based on parent- and self-ratings across SCARED/SCAARED in the whole sample. Our study had limited participants; as such, rather than computing independent inter-rater agreement among the children/adolescent (N = 14) vs. adult groups (N = 3), the caregiver- and self-report ratings among these samples were qualitatively examined. Finally, given the observed trend of increased proportion of participants with clinical classification of anxiety among adults compared to the children/adolescent group (Tables 2 and 3), point biserial correlations were computed to examine the associations between a clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorder and Total Anxiety composite across informant type (caregiver, self-report). Statistical analyses were computed with SPSS version 26.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Clinical sample characteristics

Table 1 outlines participant characteristics— including diagnostic history of anxiety disorder, intellectual disability, language disorder, and autism spectrum disorder—based on parent report of developmental history. Approximately half of our sample had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and the majority were diagnosed with intellectual disability. Three participants had prior diagnosis of language disorder. Importantly, cognitive testing was not part of this research study; thus, intellectual functioning estimates are not available to ascertain the extent of impairment. Mann–Whitney U Test did not detect group differences in parent- or self-reported anxiety (SCARED/SCAARED Total Score) based on diagnostic history of intellectual disability, language disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

| WSS sample | |

|---|---|

| N | 18 |

| Mean age in years (SD) [range] | 15.61 (7.84) [8.12–33.94] |

| Sex | 7F |

| Anxiety disorder | 9 (50%) |

| History of behavior therapy | 9 (50%) |

| History of medication treatment | 7 (56.25%)a |

| Intellectual disability | 14 (77.77%) |

| Language disorder | 3 (16.66%) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 10 (55.55%) |

- Note: The above diagnoses are based on parent report of the child's medical history. Cognitive testing was not completed as part of this study.

- a Two caregivers did not completed questions regarding their child's history of medication use; thus, this proportion represents those who reported medication treatment out of the 16 respondents.

Nine out of the total sample (N = 18) were clinically diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (50%) prior to this study. Specifically, seven of those below 18 years of age (46.67%) and two of all adults (66.67%) had a history of clinical anxiety. Of the nine participants with an anxiety diagnosis, all but two underwent a psychiatric or psychological evaluation (77.77%), yielding a clinical diagnosis adhering to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5). One caregiver did not respond to intake questions regarding the nature of the anxiety disorder diagnosis (i.e., the type of health professional who provided the diagnosis), and another caregiver indicated their child's pediatrician determined the classification, thus, it remained unclear if the DSM-5 criteria were applied.

Half of our total sample had a history of behavioral or psychotherapy to address anxiety or behavioral problems (50%). Eight participants out of those under 18 years of age (53.33%) and one out of all adult participants (33.33%) were reported to have had or currently undergoing treatment. All but two caregivers reported their child's history of using psychotropic medication to address anxiety or behavioral concerns. Of these respondents, nine (56.25%) were either currently or previously on medication treatment. About half of the child/adolescent group had a history of medication use (53.84%) compared to two out of the three adults with WSS (66.66%). Those with a history of medication use had more elevated parent-ratings of anxiety on the SCARED/SCAARED compared to those without the treatment history (U = 53.50, p = 0.02) (medication use: Meanrating = 31.66, no medication use: Meanrating = 13.00). However, this effect was not observed based on self-informant ratings (medication use: Meanrating = 33.77, no medication use: Meanrating = 25.66). No group differences in self- or parent-ratings of anxiety were observed based on behavioral treatment history.

3.2 Anxiety ratings across informants and developmental groups

Table 2 outlines the average ratings by parents and children/adolescents with WSS. Among the whole participant sample, Friedman tests revealed significantly more elevated ratings by participants compared to their caregivers (self- vs. parent-ratings) in Panic Disorder, χ2 = 8.06, p = 0.005, and Social Anxiety, χ2 = 4.00, p = 0.046. These effects survived Benjamin Hochberg correction with a false discovery rate of 10%. Among the children/adolescent group, similar pattern of results was observed in Panic Disorder, χ2 = 6.23, p = 0.013, and Social Anxiety, χ2 = 3.76, p = 0.052, albeit the latter effect did not persist following correction for multiple comparisons. No other differences in parent- and self-ratings were observed in anxiety subtypes between the whole sample and the children/adolescent subgroup.

| Mean (SD) [range] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children/adolescents with WSS (SCARED) | Adults with WSS (SCAARED) | |||

| Parent-report (N = 15) | Self-report (N = 14) | Parent-report (N = 3) | Self-report (N = 3) | |

| Panic Disorder | 3.66 (3.67) [0–12] | 6.21 (5.33) [0–15] | 14.33 (6.42) [7–19] | 15.33 (7.37) [7–21] |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 6.00 (3.66) [0–13] | 7.00 (4.93) [0–17] | 15.33 (5.68) [9–20] | 16.00 (3.60) [13–20] |

| Separation Anxiety | 5.33 (3.01) [0–10] | 6.78 (4.00) [0–16] | 7.00 (2.64) [4–9] | 7.00 (4.00) [3–11] |

| Social Anxiety | 3.06 (3.47) [0–13] | 5.57 (3.79) [0–12] | 8.00 (5.56) [3–14] | 10.33 (3.78) [6–13] |

| School Phobia | 0.93 (1.48) [0–4] | 0.92 (1.89) [0–5] | - | - |

| Total Anxiety | 19.00 (12.07) [2–47] | 26.50 (15.29) [2–53] | 44.67 (18.82) [23–57] | 48.66 (17.89) [29–64] |

- Note: On the SCARED, raw scale scores at or above 7 in Panic Disorder or Somatic Symptoms, 9 in Generalized Anxiety Disorder, 5 in Separation Anxiety, 8 in Social Anxiety and 25 in Total Anxiety are considered clinically significant. On the SCAARED, clinical level is determined when raw scale scores meet or exceed 5 in Panic Disorder or Somatic Symptoms, 12 in Generalized Anxiety Disorder, 3 in Separation Anxiety, 7 in Social Anxiety and 23 in Total Anxiety.

Despite the differences across informant ratings, generally the proportion of participants that met clinical cutoff across anxiety types was sizeable based on parent (33%) and participant responses (64%) (Table 3). Among the anxiety subtypes, most participants (66%) and parents (82%) rated clinically significant problems with Separation Anxiety. In our whole sample, about 16% of the parents of children with WSS rated them in the clinically significant range in Social Anxiety, 27% in Panic Disorder, 33% in Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and 72% in Separation Anxiety; with these rates even more elevated based on self-informant ratings.

| Percent of participants with WSS meeting clinical level | Inter-rater agreement Fleiss Kappa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | Children/adolescents | Adult | |||||

| Parent-report (N = 18) | Self-report (N = 17) | Parent-report (N = 15) | Self-report (N = 14) | Parent-report (N = 3) | Self-report (N = 3) | Total sample (N = 17) | |

| Panic Disorder | 27.77% | 47.05% | 13.33% | 35.71% | 100% | 100% | 0.37 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 33.33% | 52.94% | 26.66% | 42.85% | 66.66% | 100% | 0.40 |

| Separation Anxiety | 72.22% | 82.35% | 66.66% | 78.57% | 100% | 100% | 0.46 |

| Social Anxiety | 16.66% | 35.29% | 6.66% | 28.57% | 66.66% | 66.66% | 0.24 |

| School Phobia | - | 21.42% | 20% | 21.42% | - | - | 0.57 |

| Total Anxiety | 33.33% | 64.70% | 20% | 57.14% | 100% | 100% | 0.41 |

Overall, parent ratings of anxiety increased with age, r = 0.56, p = 0.016, but self-ratings of anxiety were consistently elevated across age, r = 0.36, p = 0.15. These results should be considered with caution given our limited adult participants. Notably, this correlation was not observed among the child/adolescent participants alone, r = −0.08, p = 0.77; thus, it is possible the age effects are seen across lifespan rather than being limited to childhood.

3.3 Inter-rater agreement

As shown in Table 3, inter-rater agreement in total anxiety and subtypes across our whole sample was generally poor, although qualitative inspection of self- and parent-ratings showed a pattern of greater congruence in the limited adult participants than children/adolescents. McNemar's tests revealed a marginally significant effect whereby a larger proportion of participants met clinical level of overall anxiety based on self-ratings when compared to parent responses in the children/adolescent subgroup, p = 0.063, and the whole sample, p = 0.063.

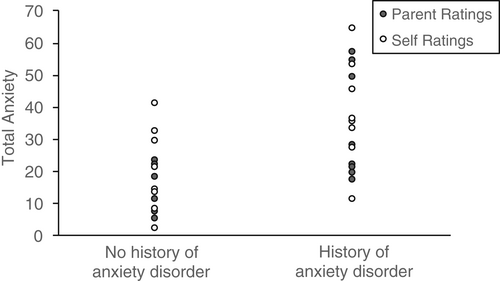

3.4 Reported history of anxiety disorder correlates with parent proxy and self-ratings of anxiety

As shown in Figure 1, history of anxiety was associated with Total Anxiety composite as rated by parents (r[18] = 0.66, p = 0.003) and participants (r[17] = 0.57, p = 0.015).

4 DISCUSSION

In brief, our study findings showed a relatively high rate of anxiety among those with WSS, particularly when reported from the affected persons as compared to caregivers. Among anxiety types, Separation Anxiety was most consistently reported by parents and individuals with WSS on an anxiety-screening inventory. Finally, clinical anxiety was more likely observed by parents' proxy ratings of anxiety with age, whereas those affected by the neurodevelopmental disorder consistently report elevated problems with anxiety across developmental stage.

In brief, poor agreement was observed between parent and self-ratings on a common anxiety screener, which has been similarly reported in prior research involving situational anxiety (e.g., dental anxiety, Patel et al., 2015) and other psychopathology among those with intellectual disability (Scott & Havercamp, 2018) and neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, Kaat & Lecavalier, 2015). Other investigations involving proxy and self-respondents of subjective psychosocial functioning such as perceived quality of life similarly found poor concordance (Simoes & Santos, 2016). Altogether, diagnostic assessment for mental health among those with WSS should incorporate multiple respondents, as individual proxy's responses for subjective psychosocial functioning may be biased by multiple factors including respondent's emotional functioning and social/cultural factors (Barney et al., 2020).

Across both parent and self-informants, elevations in the total anxiety composite on the SCARED/SCAARED were associated with a history of a clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorder. However, the proportion of participants that met clinical threshold for anxiety based on the parent SCARED/SCAARED was slightly lower than those who had a reported history of a diagnosis of anxiety disorder. These findings suggest that the inventory may be adequate to use as a gross screener of anxiety severity but result in an underestimate of anxious distress when clinically applied in isolation with only proxy respondents.

This pattern of results highlights the vital need to supplement screening measures like SCARED/SCAARED with a comprehensive interview and clinical observations in the diagnostic assessment of psychopathology. The majority of mental health screening inventories like SCARED were initially developed with individuals under typical development and not constructed for those with neurodevelopmental disorders. Those with more severe cognitive impairment such as intellectual disability or minimal verbal skills may yield a different factor structure in such screeners, as the items included may not represent the constellation of symptoms commonly observed among these individuals. In effect, more research is needed to shed light on the symptom composition of anxiety types among those with neurodevelopmental disorders, in addition to the psychometric properties of existing screening inventories among affected individuals, particularly those with more severe cognitive, sensorimotor, or physical impairment. Collectively, these efforts may guide the development of mental health diagnostic tools that better represent the clinical features of those with developmental disabilities.

The rate of anxiety by history and by current clinical symptoms are elevated in our sample in contrast to prior observational studies or case reports (Chan et al., 2019), which reported about 10% of their cohort of persons with WSS had a history of anxiety. However, our study findings, which showed approximately 33% of participants met clinical threshold on the SCARED/SCAARED, were similar to Durand et al. (2022), which reported 38% of their sample with WSS yielded a SCARED total score indicative of clinical anxiety. Discrepancies in findings may be due to methodological differences as published literature on those with WSS largely relies on retrospective chart review or natural history rather than standardized screening tools. Importantly, the proportion of our sample that met clinical levels of anxiety (based on parent- and self-ratings) is substantially greater than 12 month prevalence estimates documented among those 13 years and older in the United States (Panic Disorder: 6.8%, Generalized Anxiety Disorder: 2.0%, Separation Anxiety Disorder: 1.2%, Social Phobia/Anxiety: 7.4%) (Kessler et al., 2012); and general pooled prevalence of anxiety among youth with intellectual disability (5.4%) (Maiano et al., 2018). Future clinicians working with persons with WSS should consider a comprehensive assessment of mental health symptoms, including multiple informants' perspectives (e.g., parents, teachers, self) to measure clinical features and functional deficits across settings and to avoid diagnostic overshadowing to intellectual disability. Routine monitoring for anxiety in early childhood for affected individuals is necessary to ensure prompt introduction to behavior intervention as needed, as self-ratings provided by our participant sample suggest clinical concerns for psychopathology permeates across development.

Anxiety is a behavioral feature in WSS that may be a viable treatment target in future clinical trials and warrants more detailed investigation. Research utilizing animal models has shown deficiency in KMT2A through ablation in the forebrain (Jakovcevski et al., 2015) and ventral striatum yields increased anxiety and reduced long-term potentiation of medium spiny neurons (Shen et al., 2014), implicating the role of KMT2A in the down regulation of synaptic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex and frontostriatal circuits which have been linked to affective processing, fear or avoidant behaviors, and anxiety disorders (Cardinal et al., 2002). Accordingly, prospective research should compare behavioral profiles of MDEMs with similar aberrations in epigenetic machinery such as Kabuki syndrome (KS). KS1 is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding KMT2D, a member of the same family of histone lysine methyltransferases as KMT2A, which is disrupted in WSS. The KMT2 family of proteins methylates H3K4, and pathogenic variants in KMT2D have already been shown to cause elevated risks of anxiety compared to sibling controls in KS (Kalinousky et al., 2022). Cross-MDEM comparisons will elucidate shared mechanisms for developmental trajectories of select psychopathology. Importantly, such epigenotype-phenotype investigations will inform whether those with WSS may benefit from intervention efforts (e.g., introduction of ketogenic diet or histone deacetylase inhibitor) that have shown promising postnatal reversal of functional deficits in KS (Benjamin et al., 2017; Bjornsson et al., 2014).

Our findings should be considered in the context of several study limitations, including our limited sample size, limited racial and ethnic diversity, and heterogeneity in participants' demographic background (e.g., wide range in age albeit a small cluster of adults). Our sample comprised of all White participants, which may reflect disparities in access to internet and/or electronic devices, given surveys were distributed remotely. The patient advocacy groups that supported our participant recruitment utilized social media platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook) and the WSS Foundation website—all of which require digital access. It is possible that our sample represents families with more financial resources. Moving forward, it will be important for investigations involving rare diseases such as WSS to consider strategies to increase healthcare and research access for patients of disadvantaged and minoritized backgrounds. While digital research platforms have widened research opportunities for families who reside in more suburban areas distant from large academic medical centers, more research with this model of care is needed to determine its sensitivity in mental health screening and patient management.

As noted above, it should be highlighted that the SCARED/SCAARED is a screening tool and thus should not be considered diagnostic of anxiety disorders alone. Instead, future research may want to consider utilizing this tool in conjunction with other inventories that have been well validated in clinical samples of individuals with intellectual disabilities such as the Anxiety, Depression and Mood Scale (ADAMS) or Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC). While our study findings may offer preliminary support to further explore affective symptoms in those with WSS, application of multiple instruments dedicated to measuring these features among those with cognitive and/or sensorimotor impairment is necessary, as anxiety-related behaviors may present differently in these individuals. For example, the SCARED may not adequately pick up some behavioral features of anxiety that may be more prevalent among neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ritualistic and compulsive behaviors, perseverative tendencies, and restricted interests (Lidstone et al., 2014; Moskowitz et al., 2019; Oakes et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2019; Uljarević & Evans, 2017).

Other proxy respondents such as teacher informants may shed light whether anxiety is observed across settings or may be situationally driven. Provider-rated measures may also offer clinicians a more uniform approach in examining behaviors consistent with anxiety. Clinicians and researchers working with those with neurodevelopmental disorders such as WSS should also consider integrating multiple anxiety screening measures, including metrics for trait vs. state anxiety and to determine stability of such concerns. Psychophysiological markers of anxious distress, such as skin conductance, electroencephalography, heart rate, or heart rate variability, should be integrated with behavioral measures to identify aberrations in neurobiological mechanisms resulting from the cascading epigenetic imbalance. Our study did not monitor the specific types of psychotropic medication used for treatment (e.g., use of anxiolytic, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, etc.), duration of behavioral intervention, or current vs. past engagement in therapy, which should be incorporated in future studies. Accordingly, these results may represent an underestimate of clinical anxiety as the reported symptomatology may represent residual concerns following multiple treatments. Finally, a less conservative method was used to correct for multiple contrasts in our study. Subsequent investigations with larger clinical samples and statistical power should consider a more prudent approach.

Despite these methodological weaknesses, to our knowledge, our study is the first to systematically identify the elevated prevalence and risk for anxiety among those with WSS across age, and to reveal the potential underreporting of internalizing symptoms by caregivers, underscoring the significance of a comprehensive assessment of psychosocial functioning in early childhood. Future investigations on the anxiety profile of WSS will benefit from applying interdisciplinary research methods to isolate specific metrics of anxious distress with high ecological validity, which may be more precise target outcomes for clinical treatment trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the patients and their families who participated in this study, as well as acknowledging the support of the Wiedemann–Steiner Syndrome Foundation.

FUNDING INFORMATION

R.N. and H.T.B. are supported by grants from the WSS Foundation, J.A.F. has support from The Hartwell Foundation (Individual Biomedical Research Award) and the NIH (K08HD086250), and J.H. has support from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (K23HD101646). This study was also supported by Kennedy Krieger IDDRC NIH (P50HD103538).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Bjornsson is a consultant for Mahzi therapeutics. Dr. Harris receives research funding from Oryzon Genomics.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.