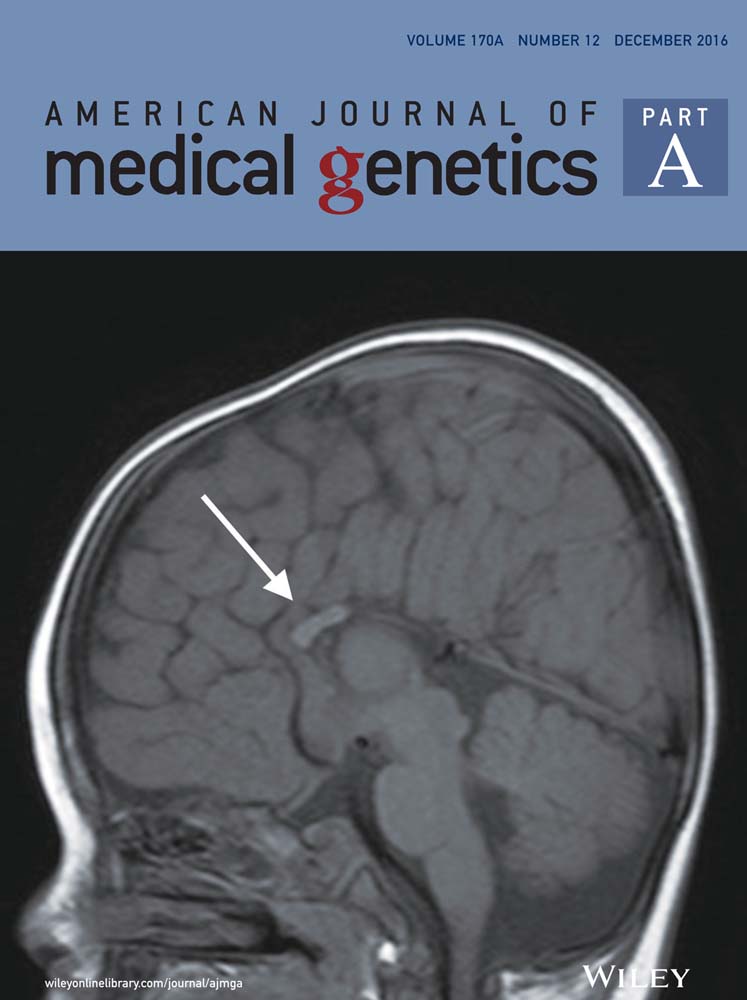

Concomitant 11p15.4-p15.5 duplication and terminal 22q13.33 deletion in a patient with features of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome

TO THE EDITOR

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (BWS, OMIM 130650) is a clinically heterogeneous pediatric overgrowth disorder that can be attributed to various molecular etiologies [Choufani et al., 2013; Mussa et al., 2015]. Clinical features of BWS can include macroglossia, organomegaly, omphalocele, earlobe creases and pits, and symmetric or asymmetric growth that continues throughout childhood [Choufani et al., 2013; Mussa et al., 2016]. Importantly, children with BWS have an increased risk for embryonal tumors, including Wilms tumor, hepatoblastoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and adrenocortical carcinoma [Choufani et al., 2013; Mussa et al., 2016]. While 98–99% of BWS cases result from the unbalanced expression of imprinted genes on the 11p15.5 region due to point mutations, epigenetic or genomic alterations, approximately 1–2% are due to cytogenetic rearrangements [Choufani et al., 2013; Mussa et al., 2015].

Deletions involving the chromosome region 22q13.33, also known as Phelan–McDermid syndrome (PMS, OMIM 606232), are the result of either de novo terminal or interstitial deletions, or less commonly by unbalanced chromosomal rearrangements involving 22q13.33 [Wilson et al., 2003; Dhar et al., 2010; Misceo et al., 2011; Phelan and McDermid, 2012; Macedoni-Lukšič et al., 2013]. Clinical features of PMS are highly variable and can include global developmental delay, intellectual impairment, hypotonia, severely delayed or absent speech, autism, or autistic-like behavior, and seizures [Phelan and McDermid, 2012]. The PMS proposed critical region (22q13.33) includes SHANK3, ACR, and RABL2, although many other genes in larger deletions may have a phenotypic role. Recently, several studies have narrowed the PMS critical region to the SHANK3 gene [Dhar et al., 2010; Macedoni-Lukšič et al., 2013], which also appears to be the most likely candidate for neurological impairments [Luciani et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2003; Phelan and McDermid, 2012].

We report a 6-week-old Caucasian female with a complex karyotype involving rearrangements between chromosomes 11, 22, and an unknown acrocentric chromosome resulting in an 11p15.4-p15.5 duplication, terminal 22q13.33 deletion, and marker chromosome. While the 11p15.4-p15.5 duplication is located on the distal long arm of a bisatellited chromosome 22, the marker chromosome is thought to be a remnant of the unknown acrocentric chromosome. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical report of a patient with cytogenetic abnormalities consistent with BWS (11p15.4-p15.5 duplication) and a terminal 22q13.33 deletion partially disrupting the SHANK3 gene.

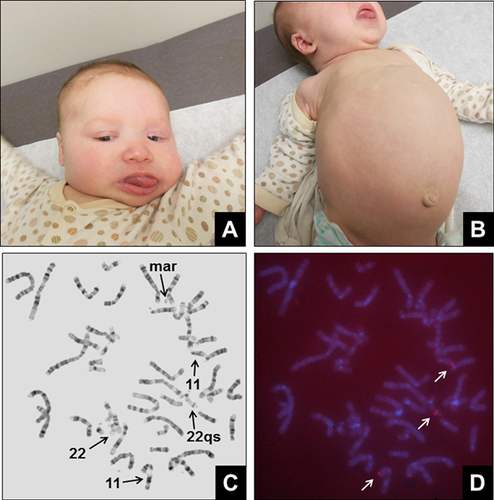

The patient was referred to the pediatric genetics clinic due to macrosomia and congenital macroglossia. She was born to a 31-year-old, G2P2002 mother and a 28-year-old father. Following an uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 40 weeks gestation, neonatal complications included hypoglycemia (35 mg/dl). Her birth weight was 5.67 kg (98.68% based on WHO weight-for-age data), length was 59.7 cm (99.35% based on WHO length-for-age data), and head circumference was 43 cm (99.98% based on WHO head circumference-for-age data). A complete physical exam was performed and revealed the following clinically significant features: broad nasal bridge, macroglossia, hepatomegaly (3–4 cm below the costal margin), and central hypotonia with increased tone in the periphery (Fig. 1A and B). An abdominal ultrasound was performed at an outside hospital and reported normal abdominal structures with no evidence of suprarenal mass. Family history includes an older sister and parents who are all phenotypically normal and of normal intelligence. There is no family history of birth defects, learning disabilities, genetic diseases, recurrent miscarriage, or consanguinity.

Classical cytogenetic analysis was performed on phytohemagglutinin (PHA) stimulated lymphocytes from a peripheral blood specimen. All 20 cells indicated a female with a bisatellited chromosome 22. In addition, 13 of the 20 cells contained a small marker chromosome (Fig. 1C). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed on metaphase cells that contained the bisatellited chromosome 22 and marker chromosome using the BAC probe RP11-27N2 (Empire Genomics, Buffalo, NY), located within the duplicated region of 11p15.4-p15.5. Hybridization of the RP11-27N2 probe was observed on the short arms of both copies of chromosome 11, in addition to the bisatellited chromosome 22 (Fig. 1D). Hybridization of RP11-27N2 was not observed on the marker chromosome.

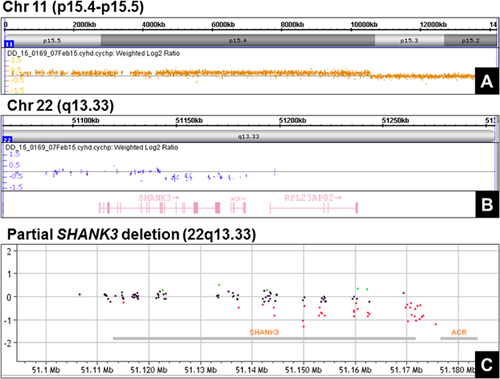

Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis was performed on purified DNA from the proband using the CytoScan HD microarray (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), and scanned with a Genechip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix). Microarray analysis revealed a concomitant 10.3 Mb duplication in the 11p15.4-p15.5 region, (Fig. 2A) and a 53 kb heterozygous deletion in the 22q13.33 region (Fig. 2B). The 11p15.4-p15.5 duplication region contained a total of 380 genes including 143 OMIM genes, and the 22q13.33 deletion region contained a total of five genes including two OMIM genes, SHANK3 and ACR. In addition, a methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification assay (MS-MLPA) (MRC-Holland) was utilized to determine the methylation status of imprinting control regions 1 and 2 (ICR1 and ICR2). The assay confirmed the duplication between probes H19-5 and CDKN1C-1b [HHA1] on chromosome 11p15.4-p15.5, and showed hypermethylation of ICR1 and hypomethylation of ICR2, a pattern consistent with a double paternal copy of the 11p15.4–15.5 region resulting in BWS. Pyrosequencing was subsequently performed and confirmed these results.

To confirm the partial SHANK3 deletion, purified DNA from the proband was analyzed at an outside institution (Greenwood Genetic Center, Greenwood, SC) using a custom exon-specific array (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and scanned with a SureScan Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies). Microarray analysis revealed a partial SHANK3 deletion spanning exons 17–22 located within the 22q13.33 region (Fig. 2C). Importantly, the exon-specific array includes SHANK3 but no other genes within the terminal region of 22q13.3. The final karyotype of the proband was: mos 47,XX,22qs,+mar[13]/46,XX,22qs[7].ish(22qs)(RP11-27N2 +).arr[hg19] 11p15.5p15.4(230,615–10,552,968)x3,22q13.33(51,144,903–51,197,716)x1. Parental genetic studies included classical cytogenetic analysis. Both parents had normal karyotypes and were not carriers of a balanced translocation or marker chromosome.

Beckwith–Wiedemann and Phelan–McDermid syndromes are both rare with an estimated prevalence of 1/13,700 for BWS [Choufani et al., 2013], and while the incidence of PMS has not been determined, approximately 1,200 cases have been diagnosed world-wide [Kolevzon et al., 2014]. While multiple molecular etiologies resulting in BWS have been described, the majority of which involve epigenomic or genomic alterations of genes within imprinting control centers 1 (IC1) or 2 (IC2), approximately 1–2% of cases are attributed to 11p15.5 duplications [Choufani et al., 2013; Mussa et al., 2016]. The diagnosis of BWS has tremendous clinical significance as these patients have an increased risk of embryonal tumors that require early tumor surveillance protocols [Mussa et al., 2016]. Deletions spanning the 22q13.33 region that include the SHANK3, ACR, and RABL2 genes result in PMS [Luciani et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2003]. In addition, intragenic SHANK3 deletions have also been reported to produce the full clinical spectrum of PMS [Misceo et al., 2011; Macedoni-Lukšič et al., 2013]. The prompt diagnosis of PMS is also of importance, as screening protocols for hypothyroidism, hearing impairment, arachnoid cysts, and renal anomalies are recommended [Phelan and McDermid, 2012].

Our case is unique in that, it is the first reported concomitant 11p15.4-p15.5 duplication and 22q13.33 deletion that likely resulted from a complex chromosomal rearrangement involving chromosomes 11, 22, and an unknown acrocentric chromosome. Our patient presented with the typical neonatal findings of BWS. The clinical significance of the 22q13.33 rearrangement will not be known until later since most of the common phenotypic features associated with PMS, such as periorbital fullness, hypohidrosis and heat intolerance, dysplastic nails, intellectual disability, autism, and seizures present in early childhood. The only identifiable feature of PMS presented by the patient at the time of the evaluation is central hypotonia, although this is usually more severe in typical cases with 22q13.33 deletions and it persists in adulthood, unlike in BWS. In addition, the molecular abnormalities are also rare for each respective syndrome (11p15 duplication for BWS, unbalanced chromosomal rearrangement for PMS). Furthermore, this case illustrates that a multifaceted approach may be necessary to resolve complex chromosomal rearrangements in constitutional disorders.