Influence of hearing loss and cognitive abilities on language development in CHARGE Syndrome

Abstract

Hearing loss and cognitive delay are frequently occurring features in CHARGE syndrome that may contribute to impaired language development. However, not much is known about language development in patients with CHARGE syndrome. In this retrospective study, hearing loss, cognitive abilities, and language development are described in 50 patients with CHARGE syndrome. After informed consent was given, data were collected from local medical files. Most patients (38.3%; 18/47 patients) had moderate hearing loss (41–70 dB) and 58.5% (24/41 patients) had an IQ below 70. The mean language quotients of the receptive and expressive language were more than one standard deviation below the norm. Both hearing loss and cognitive delay had an influence on language development. Language and cognitive data were not available for all patients, which may have resulted in a pre-selection of patients with a delay. In conclusion, while hearing thresholds, cognitive abilities and language development vary widely in CHARGE syndrome, they are mostly below average. Hearing loss and cognitive delay have a significant influence on language development in children with CHARGE syndrome. To improve our knowledge about and the quality of care we can provide to CHARGE patients, hearing and developmental tests should be performed regularly in order to differentiate between the contributions of hearing loss and cognitive delay to delays in language development, and to provide adequate hearing amplification in the case of hearing loss. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Hall was the first to note that choanal atresia could be accompanied by a specific set of multiple anomalies [Hall, 1979]. In 1981, Pagon et al. first used the acronym “CHARGE” to describe the association of Coloboma, Heart disease, Atresia of the choanae, Retarded growth and development and/or CNS anomalies, Genital hypoplasia, and Ear anomalies and/or deafness [Pagon et al., 1981]. Because of increased knowledge about the syndrome, Blake revised this definition in 1998 into major and minor characteristics [Blake et al., 1998]. The major characteristics, which are the features that occur commonly in the then-called CHARGE association but rarely in other conditions, include coloboma, choanal atresia, cranial nerve involvement, and ear abnormalities. The minor characteristics, which occur less frequently or are less specific, include cardiovascular malformations, genital hypoplasia, cleft lip/palate, tracheoesophageal fistula, distinctive CHARGE face, growth deficiency, and developmental delay. In 2005, Verloes suggested changes to the diagnostic criteria, as shown in Table I a and b [Verloes, 2005]. In 2004, the causative gene was identified as CHD7 on chromosome 8q12.1 [Vissers et al., 2004] and the name changed to CHARGE syndrome (MIM, Mendelian Inheritance in Man, 214800).

| a. Major and minor signs of CHARGE syndrome Verloes [2005] |

| Major signs |

| Coloboma (iris or choroid, with or without microphthalmia) |

| Atresia of choanae |

| Hypoplastic semicircular canals |

| Minor signs |

| Rhombencephalic dysfunction (brainstem dysfunctions, cranial nerve VII–XII palsies and neurosensory deafness) |

| Hypothalamo-hypophyseal dysfunction (including GH and gonadotrophin deficiencies) |

| Abnormal middle or external ear |

| Malformation of mediastinal organs (heart, esophagus) |

| Intellectual Disability |

| b. Definition of typical, atypical, and partial CHARGE syndrome Verloes [2005] |

| Typical CHARGE syndrome |

| 3 major signs |

| 2/3 major signs + 2/5 minor signs |

| Partial/incomplete CHARGE |

| 2/3 major signs + 1/5 minor signs |

| Atypical CHARGE |

| 2/3 major signs + 0/5 minor signs |

| 1/3 major signs + 3/5 minors signs |

The presentation of the syndrome can be very diverse, with most patients showing a variable combination of multiple congenital anomalies. Hearing loss and cognitive delays are frequently described in CHARGE syndrome [Shah et al., 1998; Tellier et al., 1998]. Hearing loss, present in 80–100% of the patients, is the most common characteristic and can be due to anatomical anomalies of the middle or inner ear, to aplasia or hypoplasia of the cochlear nerve, or to middle ear disease. As a consequence, hearing in CHARGE syndrome can range from normal to profound deafness [Blake et al., 1998; Dhooge et al., 1998; Shah et al., 1998]. As one of the minor characteristics, delayed cognitive abilities are also often described in CHARGE syndrome. The delay in cognitive development varies and is rarely expressed in “Intelligence Quotient” (IQ), but is based instead on developmental age, abilities, and educational level. More than 50%, and possibly up to 75%, of patients have an intellectual development below average [Davenport et al., 1986; Blake et al., 1990; Harvey et al., 1991; Raqbi et al., 2003; Dammeyer, 2012]. Little is known about language development in this group of patients, but language delays have been described [Dammeyer, 2012]. One might argue that intellectual disability and hearing loss, or the combined presence of both, may have a strong influence on language development. Thus language development needs special attention in this vulnerable group of children with CHARGE syndrome, a finding further supported by Thelin, who found that parents rank hearing loss as the factor with the largest effect on the ability of their child to communicate [Thelin and Fussner, 2005].

The aim of this study is twofold. Firstly, we aim to improve our knowledge of hearing loss, cognitive ability, and language development in a large group of patients with CHARGE syndrome. Secondly, we want to establish an indicative dataset for a group of patients with multiple needs by analyzing the relationship of both hearing loss and cognitive abilities with language development.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

In this retrospective study, the data of patients registered at the Dutch CHARGE center of expertize (University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands) were used after written informed consent was obtained from patients or their legal representatives.

Patients who received a cochlear implant (CI) were excluded because the language development of patients with CI is the topic of a separate study. Data from the present study can be used as reference data for the evaluation of the results of language development in patients with CHARGE syndrome and CI.

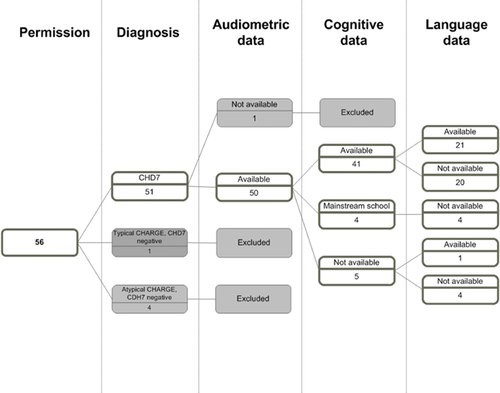

In total 56 patients (or their legal representatives) gave permission for the use of their data. Fifty-one patients had molecularly confirmed CHARGE syndrome (CHD7 mutation). The patients were classified according to Verloes’ criteria (Table I) [Verloes, 2005]. Five patients who had no molecular confirmation were excluded. One other patient was excluded because of a lack of audiometric, cognitive, and language data. For all 50 patients included, audiometric data were available. For 41 of these patients, cognitive data were available and for 22 patients language data were available (Fig. 1). The study group was divided into two groups: group A without language developmental data and group B with available language data.

Data were obtained from medical records available in hospitals, Audiologic Centers and institutes for children with hearing problems, and intellectual disability.

Audiometric Data

For 45 patients a tone audiogram was available (headphone or free-field). Per patient, between one and eight tests were available (mean 3, median 2). The average hearing loss at 0.5, 1, and 2 kHz (Pure Tone Average or PTA) of all available tests of the best ear was used. In five cases, only the objectively obtained hearing thresholds (Brainstem Evoked Response or BER) had been carried out; in these cases, the BER thresholds were used for the analysis. On the basis of the PTA or the BER thresholds, patients were categorized as normal hearing: threshold 0–20 dB; mild hearing loss: 21–40 dB; moderate hearing loss: 41–70 dB; severe hearing loss: 71–90 dB; or profound hearing loss: >90 dB. For the analysis, “functional hearing thresholds” were used, including the “aided PTA” in patients using hearing aids, and the “unaided PTA” in patients who did not use hearing aids. The patients using hearing aids were excluded from the analysis if the aided thresholds were unknown. Speech perception was measured by the NVA lists, a standardized Dutch monosyllable test [Bosman, 1989].

Cognitive Ability Tests

Cognitive data were available for 41 patients. The cognitive ability tests used in our cohort were validated intelligence tests in which the use of spoken or written language is not necessary. These tests are especially suitable for children and adults with language disabilities, like hearing impaired patients, or patients with autism or intellectual disability. The standardized tests used included the Dutch version of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-NL-II) [Bayley, 1993] and the Dutch version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Revised and Third edition (WISC-RN and WISC-III-NL) [Bruyn et al., 1986; Kort et al., 2005].

When longitudinal data were available, data from the most recent evaluation were used. Based on the non-verbal-IQ outcome or the developmental age, we categorized the patients into low IQ <70, subnormal IQ 70–85, normal IQ 86–115, and above average IQ >115. The developmental age was scaled in retrospect by psychologists skilled in assessing hearing impaired children using an informal procedure. In patients without available cognitive data, the school type was used in the descriptive analysis.

Both audiometric and cognitive data were categorized to observe the distribution among the patients and to filter small measurement differences.

Language Development Tests

Standardized age- and capacity-related tests were used, this was generally the Dutch version of the Reynell Developmental Language Scales [Reynell and Gruber, 1990], but any other standardized test was used if available. All tests are well validated and with available norms. Scores of these tests can be expressed as a standard score, percentile or an age-equivalent score. In case of longitudinal data, the data of the most recent evaluation of each patient were used. Both receptive and expressive language subtests were used. We express the language development in Language Quotient (LQ = age equivalent/chronological age*100).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 20 was used to collect all data and perform statistics. We made use of the Spearmans’ correlation test to test for significant correlations.

RESULTS

The study group consisted of 50 patients, 32 males, and 18 females. Of all patients, 33 patients had typical CHARGE syndrome, four patients had atypical CHARGE syndrome, one patient had partial CHARGE syndrome, and six did not meet the criteria. For six other patients it was not possible to score them for the Verloes criteria [Verloes, 2005].

Audiometric Data

Audiometric data were available for all 50 patients. The mean age at the most recent audiometric test was 10.9 years (median 9; minimum 5 months; maximum 48 years, SD 10.4). Table II shows the hearing threshold classification of the best ear. For three patients, only aided thresholds were retrievable, meaning they could not be included in the unaided threshold classification. For eight patients, no aided thresholds were available. The majority (83.0%) of the patients had hearing loss and were equally divided among the various categories (between 10.6% and 19.2%), with the exception of the group of patients with moderate hearing loss, who make up 38.3%. Of the total study group, 29 patients used hearing aids (including three bone-anchored hearing aid users), which resulted in better hearing thresholds that we further refer to as “functional hearing thresholds.” Ten patients wore no device due to refusal, recurrent infections (with moderate/severe hearing loss) or poor auditory responses. In four patients with poor auditory responses, CI had been considered but rejected because of cochlear nerve hypo-/aplasia or surgical risks.

| Unaided | Functional | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category hearing threshold | N | % | N | % |

| Normal (0–20 dB) | 8 | 17.0 | 9 | 21.4 |

| Mild (21–40 dB) | 5 | 10.6 | 12 | 28.6 |

| Moderate (41–70 dB) | 18 | 38.3 | 13 | 31.0 |

| Severe (71–90 dB) | 9 | 19.2 | 3 | 7.1 |

| Deaf (>90 dB) | 7 | 14.9 | 5 | 11.9 |

| Total | 47 | 100 | 42 | 100 |

| No unaided/aided data available | 3a | 8b | ||

- N, number of patients.

- a Aided, no unaided data.

- b Known as fitted with hearing aids, but no aided data available.

Cognitive Abilities

Cognitive developmental tests were available for 41 patients. Table III shows the distribution of cognitive levels within the group. The mean age of the patients at the time of the cognitive developmental tests was 10.5 years (median 9; minimum 1; maximum 56 years; SD 9.7). The majority of the patients (58.5%) had an IQ below 70. Nine patients were excluded from Table III: for the four patients who attended mainstream schools, no cognitive tests were conducted; for five other patients, no cognitive development tests were available and the school type was unknown.

| IQ | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Above average (IQ > 115) | 0 | 0 |

| Normal (IQ = 86–115) | 9 | 22.0 |

| Subnormal (IQ = 70–85) | 8 | 19.5 |

| Low (IQ < 70) | 24 | 58.5 |

| Total | 41 | 100 |

| No data available | 9 |

- N, number of patients; IQ, intelligence quotient.

Group A (Patients Without Data on Language Development)

For 28 patients, no language development data were available. Their characteristics are shown in Table IV. Four patients for whom only audiometric data were available were excluded from this table. Five patients attended or have attended mainstream schools in childhood and no language development tests had been conducted with them, but we assumed that they communicated in spoken language. All five patients had a CHD7 mutation, but none fulfilled the CHARGE criteria according to Verloes [2005].

| ID | CHD7 | CHARGE criteria | Cognitive ability | Functional hearing threshold | Speech perception | Language development | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | Positive | Negative | Normal | Normal | 100% 50 dB | Mainstream school | |

| 6 | Positive | Atypical | Normal | Moderatea | 85% 80 dB aided | No info | HA |

| 22 | Positive | Unknown | Normal | Moderate | 50% 65 dB | No info | HA |

| 51 | Positive | Negative | Normal | Moderatea | 95% 55 dB aided | No info | |

| 4 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Mild | No info | ||

| 14 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Moderate | No info | HA | |

| 49 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Normal | No info | ||

| 28 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Deaf | No info | No HA | |

| 8 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderate | Very limited | HA not accepted | |

| 24 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderate | Very limited | HA | |

| 25 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderate | Very limited | BAHA | |

| 29 | Positive | Positive | Low | Severe | Very limited | No HA, because poor auditory performance | |

| 31 | Positive | Positive | Low | Severe | Very limited | Started with CI evaluation | |

| 36 | Positive | Positive | Low | Deaf | Very limited | NvIII aplasia | |

| 37 | Positive | Positive | Low | Deaf | Very limited | HA | |

| 43 | Positive | Positive | Low | Deaf | Very limited | No HA because recurrent otitis | |

| 45 | Positive | Positive | Low | Deaf | Very limited | Parents canceled CI | |

| 52 | Positive | Positive | Low | Severe | Very limited | HA | |

| 42 | Positive | Positive | Low | Deaf | No info | nVIII hypoplasia | |

| 34 | Positive | Positive | Low | Mild | No info | BAHA | |

| 39 | Positive | Unknown | No test | Mild | Mainstream school | ||

| 48 | Positive | Negative | No test | Normal | 100% 55 dB | Mainstream school | |

| 50 | Positive | Negative | No test | Normal | Mainstream school | ||

| 18 | Positive | Negative | No test | Normal | Mainstream school |

- Number of patients, 24; HA, hearing aid; BAHA, bone anchored hearing aid.

- a Known as fitted with hearing aids, but no aided data available; four patients excluded with only audiometry available.

In ten patients, no language tests were performed because they had very limited spoken language levels. They had insufficient communication skills and communicated with pictograms, signal behavior, and finger spelling. All of these patients had an IQ below 70 and moderate to severe functional hearing thresholds. All ten patients fulfilled the CHARGE criteria according to Verloes [2005].

For nine patients, there was no information available on language development or educational level. The cognitive abilities of these patients range from normal to low. Of these nine patients, one patient (ID 51), did not meet the Verloes’ criteria [Verloes, 2005], for one patient (ID 22) this was unknown and one had atypical CHARGE syndrome (ID 6).

Group B (Language Data)

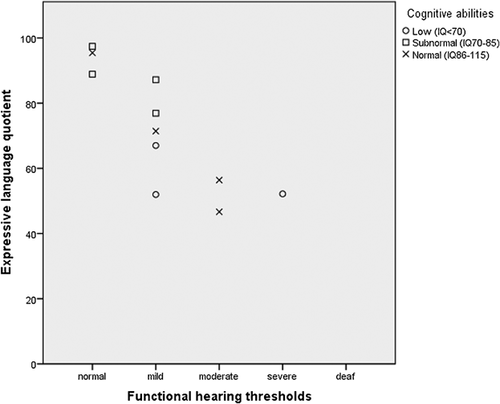

Table V presents group B, comprising the 22 patients with complete records, except for three patients (ID 17, 23, and 54) using hearing aids, but without known aided thresholds, and one patient (ID15) whose cognitive abilities are unknown. At the most recent evaluation of the language development, the age of the patients varied between 1 and 25 years, with a mean of 7.1 years (median 4.5; SD 6.7). In one patient, the receptive language age was age adequate; this patient had no hearing loss and normal cognitive abilities. One patient achieved better scores than expected for his age with subnormal cognitive abilities (IQ 75–85). The remaining patients scored below the age equivalent scores. The mean receptive language quotient of the 22 patients was 59.7 and the median was −62.0 (SD 28.47). Both the mean and the median were close to two standard deviations below the norm (85). The mean and median of the expressive language quotient were also more than one standard deviation below the norm, with 70.5 and 69.2 (SD 22.5), respectively. Cognitive abilities in this subgroup were normal in 22.7% of patients (5/22), subnormal in 22.7% (5/22), and low in 50% (11/22). The functional hearing thresholds varied from normal to deaf, with 50% of patients (11/22) showing moderate hearing loss. Patients with restricted spoken language scores used other modes of communication like sign language or sign-supported spoken language.

| Receptive language | Expressive language | Maximal speech perception | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | CHD7 | CHARGE criteria | Cognitive ability | Functional hearing threshold | CA in months (years) | LA in months | LQ | CA in months | LA in months | LQ | Max in % | dB | Max in % with HA | dB with HA |

| 3 | Positive | Atypical | Normal | Moderatea | 39 (3) | 23 | 59 | 39 | 22 | 56 | ||||

| 5 | Positive | Negative | Normal | Normal | 44 (3) | 44 | 100 | 44 | 42 | 95 | 100 | 65 | ||

| 7 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderatea | 23 (1) | 12 | 52 | 23 | 12 | 52 | ||||

| 10 | Positive | Positive | Low | Mild | 302 (25) | 18 | 6 | |||||||

| 12 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Severea | 274 (22) | 34 | 12 | |||||||

| 15 | Positive | Positive | Unknown | Moderatea | 14 (1) | 12 | 86 | 14 | 15 | 107 | ||||

| 16 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderatea | 34 (2) | 25 | 74 | |||||||

| 17 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderateb | 124 (10) | 90 | 73 | 97 | 29 | 30 | 90 | 110 | 90 | 75 |

| 19 | Positive | Positive | Normal | Moderatea | 30 (2) | 14 | 47 | 30 | 14 | 47 | ||||

| 20 | Positive | Unknown | Low | Moderatea | 171 (14) | 27 | 16 | |||||||

| 23 | Positive | Atypical | Low | Moderateb | 60 (5) | 30 | 50 | 95 | 90 | 100 | 70 | |||

| 27 | Positive | Positive | Normal | Severea | 37 (3) | 26 | 70 | |||||||

| 30 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Normal | 62 (5) | 69 | 111 | 63 | 56 | 89 | ||||

| 35 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Normal | 54 (4) | 43 | 80 | 39 | 38 | 97 | ||||

| 38 | Positive | Positive | Normal | Milda | 42 (3) | 33 | 79 | 42 | 30 | 71 | 95 | 75 | ||

| 40 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Mild | 39 (3) | 32 | 83 | 39 | 39 | 77 | 100 | 60 | ||

| 41 | Positive | Positive | Subnormal | Mild | 39 (3) | 34 | 87 | 39 | 34 | 87 | 100 | 65 | ||

| 44 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderatea | 113 (9) | 21 | 19 | |||||||

| 55 | Positive | Positive | Low | Moderatea | 194 (16) | 87 | 45 | 100 | 75 | |||||

| 53 | Positive | Positive | Low | Mild | 65 (5) | 42 | 65 | 65 | 44 | 67 | ||||

| 54 | Positive | Negative | Low | Moderateb | 96 (8) | 57 | 59 | 97 | 57 | 59 | 100 | 65 | ||

| 57 | Positive | Negative | Low | Milda | 127 (10) | 55 | 43 | 127 | 66 | 52 | 70 | 96 | ||

- N, 22; CA, calendar age; LA, language age; LQ, language quotient; HA, hearing aid; dB, decibel.

- a Aided thresholds.

- b Known as fitted with hearing aids, but no aided data available.

Two patients had “atypical CHARGE” (ID 3, 23), three did not fulfill the Verloes criteria (ID 5, 54, 57) and one patient could not be scored (ID 20).

Relationship Between Hearing Loss, Cognitive Abilities, and Language Development

Of the 22 patients in group B, four patients were excluded: three because of unknown aided thresholds, and one because of missing cognitive abilities. In the remaining 18 patients, the following significant correlations were found: between receptive language quotient and degree of functional hearing loss (Spearman P 0.006, r2 −0.622); between receptive language quotient and cognitive abilities (P 0.038, r2 0.493); and between expressive language quotient and functional hearing loss (P 0.001, r2 −0.845). No significant correlation was found between expressive language quotient and cognitive abilities (P 0.651, r2 0.154), and between cognitive abilities and hearing loss (P 0.310, r2 −0.246). Figures 2 and 3 show that the receptive language quotient and the expressive language quotient decrease with an increase of functional hearing thresholds in patients with normal or subnormal cognitive abilities.

DISCUSSION

The present study gives an overview of hearing loss, cognitive abilities, and language development of a cohort of Dutch patients with CHARGE syndrome. Large variability is shown, but the majority of the patients had moderate hearing loss and cognitive abilities were below average in slightly over half of the patients. Both hearing thresholds and cognitive abilities influenced language development, resulting in delayed language development.

The range in hearing loss in the whole study group (60–90% had moderate to total hearing loss) corresponds with that reported for CHARGE syndrome in the literature [Davenport et al., 1986; Shah et al., 1998; Jongmans et al., 2006]. Some patients had unaided hearing loss because of recurrent otitis media, refusal of hearing aids or fitting problems because of the shape of the auricle or poor auditory responses. Alternatives to conventional hearing aids, like a bone anchored hearing aid and CI, were considered in these patients. These difficulties in adequate hearing amplification were also described by Thelin and Fussner [2005] and show that it can be challenging to give the optimal therapy in children with CHARGE syndrome. Based on our results, we emphasize the importance of early screening and follow up of the hearing thresholds in order to begin adequate hearing revalidation as soon as possible because hearing loss has a big impact on language development.

Comparing the outcome of cognitive abilities with the literature is difficult because of the different tests and the different definitions of levels of cognitive ability that were used. The distribution of patients with subnormal or low cognitive abilities in our study (78%) is slightly higher compared with results from other studies [Blake et al., 1990; Harvey et al., 1991; Lasserre et al., 2013], possibly due to our exclusion, of patients attending mainstream schools with an assumed average cognitive abilities. Factors like behavioral problems (autism, obsessive-compulsive disorders, tics, attention deficits disorders) frequently described in CHARGE syndrome [Bernstein and Denno, 2005; Hartshorne et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005] were not intensively studied in the present study, but could influence development, making this a topic for further research.

In ten patients, no language developmental data could be gathered because their receptive language was highly delayed due to their cognitive delay. These patients suffered from severe hearing loss and severe cognitive developmental delays. For the five patients with mild or no hearing loss who had attended mainstream schools, we assume they had normal language development because of the educational level of mainstream schools. A possible explanation for this is that developmental tests are normally not applied at mainstream schools.

To the best of our knowledge, the language development in a cohort of patients with CHARGE syndrome has not been previously described in this detail. In group B the majority had language development and cognitive abilities more than one standard deviation below the norm, suggesting that IQ and LQ are broadly similar, confirmed by the significant correlation of cognitive abilities and receptive language quotient. This is in line with Santoro et al. who showed that cognitive developmental delay has a significant impact on communication, even if the expressive communication skills are preserved [Santoro et al., 2014]. No significant correlation of cognitive abilities and expressive language quotient was found. Particularly patients with lower cognitive abilities did not show expressive language quotients and could not be included in the calculations, probably causing a bias. In this study, we also show that patients with CHARGE syndrome with lower functional hearing thresholds reach lower levels of language development.

A shortcoming of this study is the variability in data sources. Data were collected from different professionals and institutions, leading to missing language and cognitive developmental testing data. Despite these problems, enough data were gathered to give an impression of the hearing loss, cognitive development and language development and to do an analysis of the impact of hearing loss and cognitive development on language development in CHARGE syndrome in, as far as we know, the largest group of CHARGE patients in which this has been described.

The tests described in the group B patients were probably conducted for a specific reason such as a delay in cognition and/or language development, that made knowledge about the patient's development necessary for, for instance, educational advice. Reasons for non-availability of the tests could be: patient unable to perform the test, patient performing at average levels with no reason to be tested, or tests had been conducted but were no longer available. In addition, patients with CI were omitted from the descriptive analysis. It is possible that the group with available cognitive (and language) data represented a pre-selection of patients with a developmental delay by excluding those too well-performing to have tests done and those too poor-performing to participate in language tests. If this was the case, the results of this study may not reflect the entire population of patients with CHARGE syndrome, but are biased towards to the more moderate group. In the future this could be resolved by performing a standard language and cognitive developmental test with every CHARGE syndrome patient. Although some parents of patients think the abilities of their children are underestimated by most standard tests [Thelin and Fussner, 2005], a standardized collection of data is still needed to analyze the properties of CHARGE syndrome and to improve care for these patients.

In general, we can conclude that the auditory abilities, cognitive abilities, and language development in CHARGE syndrome vary widely, but are mainly below average. Therefore, these children should be tested regularly with respect to auditory and cognitive development in order to be able to differentiate between the contributions of hearing loss and cognitive delay to delays in language development. This is especially critical for hearing loss because it has great impact on language development and adequate amplification is therefore important.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank parents of patients for giving the permission to use their data. We thank Kate McIntyre for editing the manuscript.