Disability training in the genetic counseling curricula: Bridging the gap between genetic counselors and the disability community

Abstract

Over the past two decades, disability activists, ethicists, and genetic counselors have examined the moral complexities inherent in prenatal genetic counseling and considered whether and in what ways genetic counseling may negatively affect individuals in the disability community. Many have expressed concerns about defining disability in the context of prenatal decision-making, as the definition presented may influence prenatal choices. In the past few years, publications have begun to explore the responsibility of counselors in presenting a balanced view of disability and have questioned the preparedness of counselors for this duty. Currently, the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC) only minimally includes disability training in their competencies for genetic counselors, and in their accreditation requirements for training programs. In an attempt to describe current practice, this article details two studies that assess disability training in ABGC-accredited genetic counseling programs. Results from these studies demonstrate that experience with disability is not required by the majority of programs prior to matriculation. Though most program directors agree on the importance of including disability training in the curriculum, there is wide variability in the amount and types of training students receive. Hours dedicated to disability exposure among programs ranged from 10 to 600 hours. Eighty-five percent of program directors surveyed agree that skills for addressing disability should be added to the core competencies. Establishing a set of disability competencies would help to ensure that all graduates have the skills necessary to provide patients with an accurate understanding of disability that facilitates informed decision-making. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between genetic counseling and the disability community has been widely discussed [Parens and Asch, 2003; Bauer, 2011; Dent et al., 2011; Madeo et al., 2011; Resta, 2011; Hodgson and Weil, 2012a; Peterson, 2012]. Recent articles, combined with past research, highlight the dual role of genetic counselors, who provide information about disabling conditions in the context of prenatal counseling, while acting as advocates for individuals with disabilities in pediatric and adult settings. Collectively, these articles question whether accomplishing both goals is possible and consider the obstacles that must be surmounted. Despite approaching the issue from a variety of perspectives, these articles include a number of recurring themes: (i) that by its very nature prenatal genetic counseling is inextricably intertwined with disability issues, a fact that gives rise to a unique responsibility for counselors, who must develop an accurate concept of disability, with regard to its challenges and its rewards [Santalahti et al., 1998; Asch, 1999; Parens and Asch, 2003; Hodgson and Weil, 2012a; Madeo et al., 2011; Farrelly et al., 2012]; (ii) that genetic counselors would benefit from increased interaction with and understanding of individuals with disabilities [Asch, 1999; Wertz and Gregg, 2000; Roberts et al., 2002; Parens and Asch, 2003; Hodgson and Weil, 2012a; Dent et al., 2011; Madeo et al., 2011; Peterson, 2012]; and (iii) that genetic counselors and their governing bodies have a moral responsibility to address these issues in a comprehensive way [Parens and Asch, 1999; Hodgson and Weil, 2012a; Dent et al., 2011; Madeo et al., 2011].

While addressing issues of disability goes hand-in-hand with genetic counseling practice, there are few specific requirements or guidelines for training in this area. In 2013a, 2013b, the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC) became the accrediting body for graduate programs in genetic counseling and revised/updated their standards. The only direct reference to disability is the inclusion of “disability awareness” under the section on instructional content. The ACGC does not further define “awareness,” nor does it suggest specific aspects of disability that should be addressed in preparing genetic counseling students for clinical practice. It does mandate that “clinical training and fieldwork experiences must provide students with opportunities to have first-hand experience with individuals and families affected by a broad range of genetic conditions” (http://gceducation.org/Pages/Standards [2013]). This lack of specific standards may lead to widely varied training approaches among genetic counseling programs [Teicher et al., 1998; Brown et al., 2009].

One potential measure of the success of graduate school training is the satisfaction of individuals utilizing genetic counseling services. Limited studies have explored if and how genetic counselors communicate about disability in actual practice and have found that communication is lacking at best and almost non-existent at worst. A 1998 study by Santalahti et al. found that disability was a neglected topic in genetic counseling sessions with pregnant women who had both positive and negative serum screen results. Another study surveyed patients regarding topics discussed in their genetic counseling sessions and found that counselors focused primarily on providing medical genetic information and spent minimal time discussing psychosocial effects of disability on families [Wertz, 1998]. In a study published in 2002, women at risk of carrying a child with a disabling condition were asked about their genetic counseling sessions. Ninety-one percent thought that the session provided helpful information, but 87% said that the genetic counselor did not provide information about future quality-of-life issues for a child with a disability. Furthermore, 82.6% said that the genetic counselor spoke only about the negative aspects of giving birth to a child with a disability [Roberts et al., 2002]. A more recent study conducted in Australia reviewed 21 prenatal genetic counseling sessions with women who received an abnormal result on maternal serum screening. The authors found that the majority of the sessions were spent on information giving and that the genetic counselor did most of the talking. In addition, they found a lack of dialogue about disability topics, with the genetic counselors offering information only in response to direct questioning by clients [Hodgson et al., 2010]. Lastly, a study published by Farrelly et al. [2012] analyzed simulated genetic counseling sessions conducted by practicing genetic counselors and found that 95% of counselors focused on the physical aspects of disability while only 27% discussed the social aspects. In these simulated sessions, only 38% of counselors inquired about patients' experiences with disability.

Studies have also shown that almost a third of genetic counselors have not been satisfied with the disability training obtained during their graduate programs [Teicher et al., 1998; Brown et al., 2009]. In 1998, Teicher et al. found that 98.4% of recent genetic counseling graduates believed that disability training should be included in the genetic counseling training program, and 30% felt that their training was inadequate. More than 10 years later, Brown et al. found similar results, as 28% of recent genetic counseling graduates felt that disability was not “adequately addressed” during their training. In response to these concerns, many have argued for increased opportunities for interaction with individuals with disabilities [Asch, 1999; Wertz and Gregg, 2000; Patterson and Satz, 2002; Parens and Asch, 2003; Shakespeare et al., 2009; Hodgson and Weil, 2012a]. A recent article by Madeo et al. further argues that, “graduate training programs should develop measurable outcomes by which to evaluate their efforts” [Madeo et al., 2011].

Despite the various findings of the studies mentioned above, the curriculum requirements and practice-based competencies previously determined by the American Board of Genetic Counseling (ABGC) did not mandate disability awareness or sensitivity training [ABGC.net 2010]. The new Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC) does include one mention of disability awareness in the required psychosocial course content and states in the core competencies that genetic counselors should “recognize the importance of understanding the lived experiences of people with various genetic/genomic conditions” and “present balanced descriptions of lived experiences of people with various conditions.” However, neither the core competencies nor the accreditation requirements provide guidance as to how to achieve this, nor do they define best practices (http://gceducation.org/Pages/Standards [2013]). Furthermore, little has been done to develop a comprehensive view of how accredited genetic counseling programs in North America are approaching disability training. To this end, we have conducted two studies, one in 2002 and one in 2012, that provide an evolving view of how program directors rank disability training as a prerequisite for admission to genetic counseling programs and the emphasis and importance they place on disability training in their respective curricula. The studies include an assessment of the types and extent of disability training in ABGC-accredited counseling programs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Directors from the ABGC-accredited genetic counseling programs with full or provisional accreditation were invited to participate in both studies. In 2002, after receiving approval by the Sarah Lawrence College ad hoc thesis review board, 26 program directors were identified and a packet was sent out to each director with a cover letter and survey. The survey included questions about recommendations and requirements for students applying for genetic counseling programs, the importance placed on having disability training in the application process and the various types of disability training currently offered as part of the curriculum.

In 2012, with IRB approval from Rockefeller University, 34 program directors were sent an email invitation to participate with an electronic link to a Survey Monkey questionnaire. Initial emails were followed by two reminders. In 2002, the survey questions were developed based on the author's preliminary research into the various genetic counseling programs' application requirements and curricula, as described on their school's website. While many “other” disability training opportunities were identified in the 2002 open-ended responses, for purposes of comparison and ease of survey completion, many questions were kept consistent between the two surveys.

The 2012 survey included three specific additional training opportunities and some additional questions regarding the emphasis placed on disability training in genetic counseling curricula. It also raised the question of whether disability sensitivity and awareness should be added to the ABGC core competencies. Disability sensitivity and awareness were not defined for the respondents in either study. Each section of questions on both surveys included the option for users to comment or provide further details about their responses. These open-ended responses were not formally analyzed but reviewed to better understand a respondent's answers and for quotations demonstrating common responses. Descriptive statistics were used for all quantitative questions from both studies using Microsoft Excel. It is important to note that during both studies, the accrediting body for genetic counseling training programs was the ABGC. In 2013, during the writing of this paper, the accrediting body became the Accreditation Counsel for Genetic Counseling (ACGC).

RESULTS

In 2002, the survey reached 25 genetic counseling program directors in North America and 15 were returned for a response rate of 60%. One packet was returned to sender by the postal service with a 3-month delay, so there was no time to resend the survey materials before the conclusion of the project. In 2012, the survey reached 34 active program directors and 20 surveys were completed for a response rate of 58.8%. Thirty-five percent of respondents in 2012 were from programs that did not exist in 2002. For those programs that were accredited in 2002, 61.5% had the same program director in 2002 and 2012.

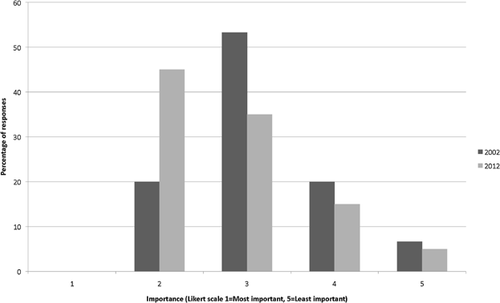

In 2002, none of the programs required that applicants have experience with disability issues. In 2012, 10% of program directors reported including this as a prerequisite. When asked to rank the importance of applicants having experience with disability using a Likert-scale of 1–5 (with 1 being the most important), the mean was 3.1 in 2002 and 2.8 in 2012 (see Fig. 1). However, many program directors reported that having such experience is taken into account and viewed favorably in the application process.

In response to questions about disability training in their respective programs, every director reported having some disability training, but there was great variability in the amount and types of training offered. Given a list of seven disability training activities, directors were asked to indicate which of these were included in their programs. Some programs incorporated one or two of these options, while others offered all seven (see Table I). Activities offered by at least 60% of counseling programs in 2012 included attending a support group for individuals with disabilities (60%), attending a workshop on the nature and history of disability (65%), attending a support group for family members of individuals with disabilities (70%), attending a workshop with parents of a child with disability (70%), and attending a workshop on appropriate language pertaining to disability (80%). When asked for additional comments, many program directors indicated there were also outside training opportunities for their students including campus or state programs (LEND, LEADS, Impact), volunteering for community activities, attending family conferences, and providing respite care. Cumulatively, the hours dedicated to disability training/exposure among programs ranged from ten to more than 600 hours during the course of the program.

| Type of disability training | % of yes responses indicating that this is offered | |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2012 | |

| Rotation with a family that has a child with a disability | 40% (6) | 45% (9) |

| Rotation at a group home or facility for individuals with disabilities | Not asked | 35% (7) |

| Workshop with parents of a child with a disability | 73% (11) | 70% (14) |

| Workshop on the nature and history of disability | 67% (10) | 65% (13) |

| Workshop on appropriate language surrounding disability | 67% (10) | 80% (16) |

| Attending a support group for individuals with disabilities | Not asked | 60% (12) |

| Attending a support group for family members of individuals with disabilities | Not asked | 70% (14) |

| Other | 80% (12) | 95% (19) |

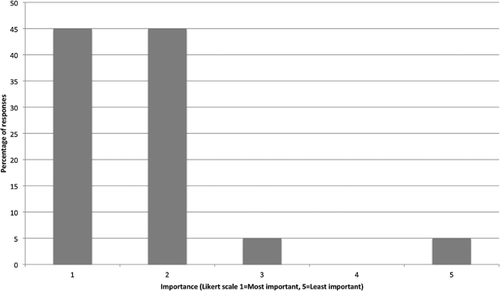

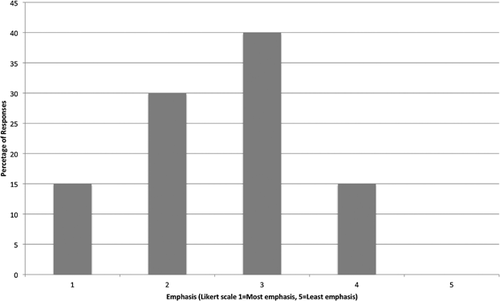

In the 2012 survey program directors were asked, “How important do you feel it is for students to be trained on disability awareness and sensitivity issues while in the program?” and, “How much emphasis do you feel is placed on disability training in your curricula?” The majority of respondents felt that such training was important (mean 1.75, with 1 being the most important). When asked how much emphasis was placed on disability training in their respective genetic counseling programs, the mean was 2.55 (see Figs. 2 and 3).

In the 2012 survey, program directors were also asked whether they thought disability awareness and sensitivity should be included in the ABGC core competencies. Eighty-five percent of respondents said these skills should be added. Almost all respondents (94%) agreed with the statement, “These skills are important for genetic counselors to have.” Three respondents indicated that these skills should not be added to the core competencies, arguing that, “they are too subjective” and “are already interwoven into what we do.”

DISCUSSION

Defining what it means to have a particular genetic condition, both practically and experientially, is a large part of the role of genetic counselors. In undertaking this enterprise, we accept a responsibility of tremendous ethical significance, as the picture we present and the guidance we offer may affect prenatal decisions and long-term outcomes. By the very nature of the profession, genetic counselors may have a much greater impact on influencing societal views of disability, which can have direct implications for individuals with disabilities and their families, both in terms of how they are perceived and how they perceive themselves. Given what is at stake, one might expect the field of genetic counseling to give pride of place to preparing graduates to address disability in a consistent and appropriate way. Yet, historically, that has not been the case.

While many programs offer great opportunities in this area, program directors approach disability training in vastly different ways and with varying depth. Lacking standardization, the likely outcome of this approach is a graduating work force that varies widely in its awareness of disability issues and its ability to navigate the complex challenges that disability presents. The literature certainly suggests that there is room for improvement, as it documents dissatisfaction on the part of some patients who feel they have not been adequately prepared on the topic of disability [Santalahti et al., 1998; Wertz, 1998; Roberts et al., 2002], on the part of genetic counselors who feel their disability training has been inadequate [Teicher et al., 1998; Brown et al., 2009; Hodgson and Weil, 2012a], and on the part of some disability advocates who believe that genetic counselors do not consistently possess or present an accurate picture of life with a disability [Shakespeare, 1998; Asch, 1999; Parens and Asch, 2003; Brasington, 2007]

So how do we bring about a more consistent approach to disability issues that optimally informs and prepares patients in a sensitive and constructive way? Certainly adding experience with disability to the list of prerequisites for applicants would ensure that genetic counseling students have more experience at matriculation. Only 10% of programs in our study have taken this approach, while other programs have focused exclusively on training students while in graduate school. The question of how best to go about disability education in genetic counseling programs is a separate issue and reaching agreement among counselors regarding what essential elements should be included would be a first step. The list of key elements provided by The American Down syndrome Congress for those expecting a child with Down syndrome may serve as a helpful guide here and could be more broadly applied to other disabling conditions [Raz, 2005]. These recommendations suggest providing “a) information that seeks to dispel common misconceptions about disability and present disability from the perspective of a person with a disability, b) information about the community-based services for children and families as well as on financial assistance programs, c) material on special needs adoption, and d) a summary of laws protecting civil rights of those with a disability.” In 2012, Farrelly et al. further proposed a number of ways to improve discussions about disability which included the following: “1) broaden the discussion of disability to include social aspects of quality of life; 2) investigate client perceptions and experience; 3) make clients aware of resources; and 4) offer all possible options to prenatal clients including pregnancy termination, continuation of pregnancy, raising the child at home or special needs adoption.”

In addition to reaching agreement on optimal content for discussions, disability advocates have also suggested that exposure to individuals with disabilities outside of a medical setting is an effective way of building comfort in discussing disability and facilitating informed decision-making [Saxton, 1996; Patterson and Satz, 2002; Brasington, 2007; Shakespeare et al., 2009]. They further argue that this approach has the effect of tempering beliefs engendered by the traditional medical model and encourages the development of a more nuanced view of disability [Saxton, 1996; Patterson and Satz, 2002; Brasington, 2007; Hodgson and Weil, 2012b]. Shakespeare et al. also argue that, “perhaps the most dramatic learning can come when it is a peer who is disabled, rather than a patient” and advocate adjusting admissions procedures so that “suitably qualified people with disabilities can become health professionals.”

While there are no data to suggest that standardizing disability training among genetic counseling programs would improve the genetic counseling services provided to patients, we hypothesize that this causative link may exist. Adding key disability-related skills to the ACGC core competencies would prompt focused consideration of the subject and hopefully lead to best practice guidelines designed to ensure that all genetic counselors enter the field with a consistent and appropriate skill set. According to our research, the majority of program directors support including disability issues in the competencies for genetic counseling programs.

Before moving forward, however, we must address some major limitations of our studies. First, there is little research to suggest what types of disability training are most effective in preparing genetic counselors to address disability. Perhaps more difficult to address, is the lack of consensus among genetic counselors regarding the content and timing of the information to be given to patients [Parens and Asch, 1999; Roberts et al., 2002; Hodgson and Weil, 2012b].

In laying a foundation for standardization, some areas to consider include: (i) “the knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of the disability community towards genetic counseling” [Madeo et al., 2011], (ii) the messages patients are receiving from genetic counselors regarding disability (iii) genetic counselors' views on disability [Ormond et al., 2003], and (iv) the most effective training methods to build awareness, sensitivity, and a comfort level with disability. This combined research could then be used to improve the curricula and develop more concrete disability-related core competencies for genetic counseling training programs.

While the studies, we undertook shed light on the subject, we acknowledge important limitations of these studies. First, despite a 60% response rate, these findings may not be representative of the genetic counseling programs collectively, as there might be a response bias in the directors that chose to participate in the study. Second, given the complex nature of disability issues and, presumably, the lack of a common language to describe this work across the field, it appeared to us that respondents occasionally interpreted the questions in ways not intended by those conducting the study. Lastly, while this study identified categorical descriptions of various training curricula, it shed little light on actual specifics of these training programs and/or the efficacy of each. It also did not distinguish between what counseling programs offer as opposed to what they require regarding disability education.

The issue of how we approach and define disability sits at the very heart of our discipline and at the heart of societal perceptions of our discipline. As such, it is vitally important that we address the topic in a comprehensive and focused way. This work merits continued discussion about disability issues, additional research, and increased emphasis on disability awareness in genetic counseling training programs. In doing so, we will be able to provide better services to our patients and hopefully begin to bridge the gap between genetic counseling and the disability community.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the program directors for their participation and constructive responses. We are grateful to Caroline Lieber, MS, CGC, Laura Hercher, MS, CGC, and Dr. Martha Satz for their thoughtful feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Lastly, we appreciate the detailed comments from the anonymous reviewers throughout the submission process.