The perinatal presentation of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome

Abstract

There is limited information available related to the perinatal course of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (CFC) compared to other syndromes within the Ras–MAP kinase pathway (rasopathies) such as Noonan and Costello syndrome. Retrospective chart review revealed four cases of CFC with molecular confirmation between 2005 and 2012 at Hawaii's largest obstetric and pediatric referral center. We report on details of the prenatal, neonatal, and infancy course and long-term follow-up beyond infancy in two patients. This report includes novel features including systemic hypertension, hyponatremia, and chronic respiratory insufficiency, not previously reported in CFC. We provide pathologic diagnosis of loose anagen hair in one patient. Some of these findings have been reported in the other rasopathies, documenting further clinical overlap among these conditions. Molecular testing can be useful to differentiate CFC from other rasopathies and in counseling families about potential complications and prognosis. We recommend a full phenotypic evaluation including echocardiogram, renal ultrasound, brain imaging, and ophthalmology examination. We additionally recommend close follow-up of blood pressure, pulmonary function, and monitoring for electrolyte disturbance and extra-vascular fluid shifts. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (CFC) is a rare genetic disorder that shares overlapping clinical features with other conditions caused by mutations in the RAS–MAP kinase signaling pathway (rasopathies), especially Noonan and Costello syndrome. Other entities involving the Ras/MAP kinase pathway include Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (previously refered to as LEOPARD syndrome), gingival fibromatosis type 1, neurofibromatosis type 1, capillary malformation–arteriovenous malformation, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, and Legius syndrome [Tidyman and Rauen, 2009]. Most patients with CFC have mutations in BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, or MAP2K2 [Rauen, 2007]. Although, there is literature describing the phenotype and general clinical features of CFC [Roberts et al., 2006; Armour and Allanson, 2008; Allanson et al., 2011; Abe et al., 2012], there is little information describing the perinatal course of CFC. Prenatally, polyhydramnios is a common finding and is often associated with premature birth, reported in approximately 50% of CFC patients [Armour and Allanson, 2008; Allanson et al., 2011]. Prematurity is a potential confounding factor in examining the perinatal clinical features and course of CFC. Other prenatal ultrasound findings reported in CFC patients include hydronephrosis, cerebral ventriculomegaly, macrosomia, increased nuchal translucency, and cystic hygroma [Witters et al., 2008; Allanson et al., 2011; Abe et al., 2012]. The aim of this report is to describe the prenatal, neonatal, and infant courses of four consecutive CFC patients. This information may help guide clinicians in the management of CFC patients and in the counseling of their families.

CLINICAL REPORT

A retrospective chart review identified four patients with CFC born between 2005 and 2012 at Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children in Honolulu, Hawaii. All had molecular confirmation of the diagnosis. See Table I for a summary of their clinical characteristics. Reported ages at the various significant time points reported in the summaries below reflect the chronological age of the patients and are not adjusted for gestational age.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at birth | 33 weeks | 39 weeks | 29 weeks | 33 weeks |

| Prenatal characteristics | ||||

| Polyhydramnios | + | + | + | + |

| Cystic hygroma | − | + | + | − |

| Hydronephrosis | + | − | − | + |

| Neonatal characteristics | ||||

| Large for gestational age | − | + | + | − |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | + | + | + | − |

| Hypertensiona | + | − | + | − |

| Hydronephrosis | + | − | + | + |

| Pleural effusion | − | − | + | + |

| Respiratory support at NICU dischargea | Tracheostomy | − | Tracheostomy | Supplemental oxygen later started after readmission at age 5 months |

| Hyponatremiaa | + | − | + | + |

| Gastrostomy tube | + | − | + | + |

| Failure to thrive | + | + | + | + |

| Seizures or abnormal EEG | + | − | − | + |

| Abnormal brain MRI | −b | No brain imaging | No brain imaging | IVH hydrocephalus periventricular leukomalacia |

| Cataracts | − | − | + | + |

| Hearing loss | + | − | Not tested | + |

| Severe global developmental delay | + | + | + | + |

| Molecular diagnosis | BRAF p.Val487Gly | BRAF p.Gln257Arg | MAP2K1 p.Val60Gly | MAP2K2 p. Lys61Glu |

- a Clinical feature not previously reported for CFC.

- b Normal at age 6 weeks, acquired microcephaly with no further imaging.

Patient 1

A male infant was born prematurely by vaginal delivery at 33 weeks gestation due to premature rupture of membranes and spontaneous labor to a 45-year-old G10 P9 mother and a 52-year-old father. The prenatal course was complicated by late presentation to prenatal care, and the estimated date of confinement was estimated by an ultrasound performed at 27 weeks gestation. There was a poorly documented history of gestational diabetes type A1, but according to available records, hyperglycemia did not complicate the perinatal course. Severe polyhydramnios and unilateral hydronephrosis were detected 1 week prior to delivery. Positive pressure ventilation was given in the delivery room for poor respiratory effort. Apgar scores were 6 and 9 at 1 and 5 min. The BW was 2.174 kg (75th centile), BL was 44 cm (65th centile), and OFC was 31.5 cm (75th centile). Physical examination was significant for hypotonia, tall forehead with upslanting palpebral fissures, large ears, thickened nose, wide and flat nasal bridge with prominent anteverted tip, mild micrognathia with glossoptosis, hirsutism, and bilateral cryptorchidism.

The infant was treated in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where non-invasive respiratory support was continued for respiratory distress. He sustained a left grade II intra-ventricular hemorrhage (IVH) documented by head/brain ultrasound. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was unremarkable at age 6 weeks. A tracheostomy was placed at age 1 month due to upper airway obstruction and tracheomalacia. He was eventually transitioned to tracheostomy collar without ventilator support or supplemental oxygen by age 5 months. A gastrostomy tube was placed at age 3 months due to severe dysphagia and gastroesophageal reflux. Hyponatremia (serum sodium 127 mmol/L) was first noted at age 18 days and persisted through age 37 days, during, which time he was on full enteral feeds. Evaluation for hyponatremia included a normal serum cortisol, androstenedione, testosterone, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, renin, and aldosterone levels. Urine sodium was low at <20 mmol/L, urine osmolality 468 mOsm/kg H2O, and serum osmolality 277 mOsm/kg H2O. The hyponatremia did not respond to fluid restriction. Sodium supplements were briefly used from age 37 to 44 days. Echocardiograms at age 1 and 6 weeks were unremarkable. Hydralazine was started for idiopathic hypertension (systolic blood pressures 100–120 mmHg) at age 3.5 months. Renal ultrasound revealed mild left hydronephrosis with normal renal artery perfusion by Doppler. Severe bilateral hearing loss was documented by auditory brainstem response (ABR) at age 6 weeks.

He was eventually discharged at age 5 months to a long-term care facility where he remains. His weight and length both fell below the 3rd centile by discharge at age 5 months. He had multiple re-admissions to the hospital for respiratory complications. Follow-up echocardiogram at age 18 months revealed left ventricular hypertrophy, especially of the inter-ventricular septum. Hypertension was treated with spironolactone/hydrochlorothiazide and clonidine. He was again treated with sodium supplements for hyponatremia. At age 6 years he continues to exhibit severe failure to thrive despite gastrostomy feedings, with length and weight below the 3rd centile. He has acquired microcephaly (OFC 47.8 cm at age 6 years), and severe global developmental delay (non-verbal, cannot sit or roll independently and does not reach for objects). He has recurrent superficial skin infections and multiple pigmented nevi. Tracheostomy collar remains in place for respiratory support. Hypertension is controlled with a combination of clonidine patches, hydralazine, captopril, and spironolactone/hydrochlorothiazide. Mild left ventricular septal hypertrophy remains stable. Despite two negative EEG's done in the NICU for myoclonic jerks, he later developed a seizure disorder that is currently controlled on carbamazepine. Hyponatremia is managed through supplementation of enteral feedings (contains approximately 7,700 mg/day of sodium) with additional sodium as needed to maintain normal values. This far exceeds the recommended 1,200–1,900 mg intake for age [National Research Council, 2005]. Genetic testing was significant for a normal male karyotype (46,XY) and a mutation in BRAF exon 12, denoted p.Val487Gly, previously associated with CFC syndrome [Narumi et al., 2007; Abe et al., 2012].

Patient 2

A male infant was born at 39 weeks gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery to a healthy 22-year-old G4 P2 mother and 33-year-old father. The prenatal course was complicated by polyhydramnios and fetal cystic hygroma, with the latter resolved by delivery. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 min. He was large for gestational age (LGA) with BW 3.756 kg (90th centile), BL 47 cm (25th centile), and OFC 36 cm (>90th centile). Physical examination revealed apparent hypertelorism, posteriorly angulated ears, redundant nuchal skin extending to upper shoulders, grade II systolic cardiac murmur, hypotonia, and undescended right testis.

He was admitted to the NICU on high flow nasal cannula for respiratory distress and hypoxia, but weaned to room air within 2 days. He was able to nipple full enteral feedings. An ultrasound completed for excessive posterior nuchal skin suggested the presence of a lymphangioma. Scrotal and abdominal ultrasound showed a non-descended right testis and mild hepatomegaly. He passed his newborn hearing screen. Echocardiogram shortly after birth revealed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy involving the inter-ventricular septum with lesser involvement of the posterior wall of the left ventricle. He was discharged home at age 8 days with a weight of 3.436 kg (75th centile), still 8.5% under his birth weight.

The excess nuchal skin was resected at age 1 month; pathologic diagnosis was consistent with benign adipose tissue. Serial echocardiograms showed worsening inter-ventricular septal and left ventricular wall hypertrophy, and he was started on propanolol at age 2 months. Follow-up echocardiogram at age 1 year showed stable cardiac hypertrophy. He had feeding difficulties, gastroesophageal reflux, and failure to thrive, with weight falling below the 3rd centile by age 4 months. Orchiopexy was performed at age 1 year.

When last seen at age 4.5 years, he had severe global developmental delay (did not walk until after 2 years, able to vocalize babbling sounds but no words, able to follow simple commands). He wore glasses for myopia and astigmatism. Weight remained below the 3rd centile. He had scattered pigmented nevi on exam. His cardiac status was stable and he had no new health concerns. Genetic testing showed a 46,XY karyotype and a mutation in BRAF exon 6, denoted p.Gln257Arg, a mutation previously associated with CFC syndrome [Niihori et al., 2006; Abe et al., 2012].

Patient 3

A female infant was born prematurely at 29 weeks gestation (based on an 11 week ultrasound) due to spontaneous pre-term labor. The mother was a 37-year-old G6 P3 and the father was 41-year-old. The pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and fetal cystic hygroma, with the latter resolved prior to delivery. Positive pressure ventilation and continuous positive airway pressure support were required at delivery. Apgar scores were 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 min. She was LGA with BW 1.738 kg (95th centile), BL 40 cm (75th centile) and OFC 31 cm (>95th centile). Physical examination was notable for generalized edema, prominent forehead, posteriorly angulated ears, anteverted nares, hypotonia, and short webbed neck with redundant nuchal skin.

She was gradually weaned from non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to low flow nasal cannula by age 2 months. Nissen fundoplication and gastrostomy tube placement were performed at age 3 months due to severe gastroesophageal reflux and a significant aspiration pneumonia. She did not regain her birth weight until age 3 weeks despite high calorie fortified enteral feeding. Weight gradually fell to approximately 10th centile by age 4 months. She required sodium supplementation for hyponatremia (serum sodium 126 mmol/L) from age 1 month through age 2.5 months while relatively stable on full enteral feeds and minimal respiratory support, prior to the initiation of diuretics for chronic lung disease. No laboratory evaluation was initially performed for the hyponatremia, as it was attributed to sodium wasting from premature kidneys. Head/brain ultrasound was normal at age 1 and 6 weeks. Renal ultrasound showed mild left hydronephrosis. EEG was performed for possible seizure activity and was normal. Bilateral posterior capsular cataracts were noted at age 1 month. Echocardiogram performed at birth and age 1 month was normal, but by age 2 months, there was evidence of left lateral wall segmental hypertrophy with progressive pulmonary hypertension despite treatment with sildenafil. Hydralazine was instituted for idiopathic systemic hypertension at age 3 months (systolic blood pressure 95–108 mmHg). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy progressed to involve the left ventricular posterior wall and the inter-ventricular septum.

She experienced respiratory deterioration at age 3 months, requiring stepwise escalation of respiratory support to mechanical ventilation by age 4 months despite therapy with diuretics and steroids for chronic lung disease. At age 4 months, she developed significant edema, renal insufficiency, hypoalbuminemia, hypotension requiring dopamine, and stress dose hydrocortisone, right pleural effusion, and mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis. Hyponatremia was again noted (serum sodium 120 mmol/L, with serum osmolality 258 mOsm/kg H2O, urine osmolality 350 mOsm/kg H2O, and urine sodium <10 mmol/L) despite fluid restriction. Pleural fluid studies showed 558 white blood cells per microliter (with neutrophil predominance of 62%), triglycerides 81 mg/dl, total protein <3.0 g/dl, glucose 224 mg/dl, which did not support a diagnosis of chylothorax or parapneumonic effusion. She was on multiple broad-spectrum antibiotics for clinical sepsis, although, multiple blood, urine, and pleural fluid cultures remained negative. Despite maximal medical therapy, she died 2 weeks later. The family declined autopsy. Genetic testing revealed a normal 46,XX karyotype and a de novo missense mutation in MAP2K1, denoted p.Val60Gly, not identified in either parent.

Patient 4

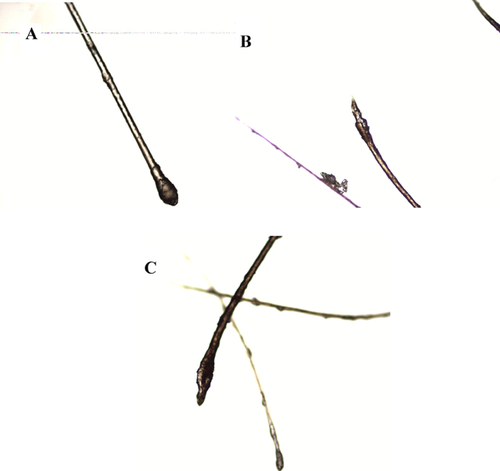

A female infant of a dichorionic diamniotic twin pair was born at 33 weeks gestation (based on a 10 week ultrasound) due to spontaneous pre-term labor to a 38-year-old G7 P4 mother and 43-year-old father. The pregnancy was complicated by prenatal diagnosis of multiple anomalies including polyhydramnios, hepatomegaly, left hydronephrosis, and growth discordance with this patient being the larger twin (Supplemental Fig. S1A and B, available in supporting information online). Prenatal chromosomal microarray revealed a 70 kb copy number gain at Xp21.1 within DMD. The healthy father was found to have the same gain, so this variant was not thought to be clinically significant. The infant was intubated in the delivery room for apnea. Apgar scores were 1, 7, and 8 at 1, 5, and 10 min. Birth weight was 2.22 kg (60th centile), BL 41 cm (10th centile), and OFC 33 cm (90th centile). The female co-twin weighed 1.88 kg (25th centile). Physical examination revealed short palpebral fissures, low-set posteriorly angulated ears, webbed neck with redundant nuchal skin, grade II systolic murmur, hypotonia, and brittle scalp hair, which easily fell out with pressure. Light microscopy of a hair follicle sample revealed misshapen anagen bulbs and a ruffled appearance of the cuticle distal to the bulb, consistent with loose anagen hair (Fig. 1).

The infant was extubated within 1 day and weaned to room air by age 2 months. Gastrostomy tube was placed at age 1 month due to poor nippling skills. She regained her birth weight within 10 days after starting on high calorie fortified enteral feedings, but weight fell below 3rd centile by age 4 months. Hyponatremia (serum sodium 125 mmol/L) at age 2.5 weeks was attributed to furosemide administration for pulmonary edema and required sodium supplementation for 2 weeks. The hyponatremia did not recur. Renal ultrasound showed left ureteropelvic junction stenosis with renal calculi. Head/brain ultrasound documented bilateral grade III IVH at age 2 days. Eye examination revealed bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia and central nuclear cataracts. Mild to moderate bilateral hearing loss was documented by ABR. Echocardiogram showed a muscular ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), and mild pulmonic stenosis, all of which resolved by age 2 months.

She was discharged from the NICU at age 2 months but has required multiple readmissions for apnea, with the most recent admission at age 5 months being the most severe, requiring mechanical ventilation for 1 week. She developed a right-sided pleural effusion that resolved after initiation of diuretics. Viral respiratory panel and blood culture were negative. She was discharged home at age 8 months on supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula and diuretics. Serial head/brain ultrasounds showed worsening ventriculomegaly secondary to communicating hydrocephalus requiring ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt placement at age 5 months. Subsequent brain MRI revealed marked decrease in white matter volume consistent with periventricular leukomalacia. An EEG was performed for evaluation of apnea and was abnormal, with rare epileptiform discharges from the occipital region indicating a pre-disposition towards seizures. Anti-epileptic drug treatment was deferred at that time after discussion with the family.

At age 12 months, she is dependent on gastrostomy tube feedings for severe dysphagia and nasal cannula oxygen supplementation. Weight is at 3rd centile but length is below the 3rd centile (−4 SD). She exhibits severe global developmental delay (non-verbal, cannot sit independently but can roll). Follow-up echocardiograms remained normal after spontaneous closure of her septal defects. She has developed severe eczematous dermatitis (Fig. 2).

Genetic testing was negative for the p.Ser2Gly point mutation in SHOC2 (Noonan-like syndrome with loose anagen hair), but reflex testing returned positive for a previously identified pathogenic mutation in MAP2K2 exon 2, denoted p.Lys61Glu, consistent with CFC syndrome [Narumi et al., 2007]. Her mother did not carry this mutation, and her father has not yet been tested. Her twin sister had an unremarkable NICU course and is currently healthy.

DISCUSSION

Our case series summarizes the prenatal and neonatal complications in four serially ascertained CFC patients from a single center (Table I). These patients share many features with other rasopathies, including facial features, cardiac abnormalities, feeding difficulties, failure to thrive, and developmental delay [Roberts et al., 2006; Armour and Allanson, 2008; Abe et al., 2012]. The three patients born prematurely had prolonged hospital courses characterized by significant cardiorespiratory complications and need for long-term respiratory support. Three patients had progressive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which was not always identified on initial echocardiogram. One patient had a structural abnormality (VSD and ASD) identified at birth, which later resolved spontaneously. One patient died after 4 months without having left the NICU. Other complications included cataracts, hearing loss, systemic hypertension, and hyponatremia.

The BRAF mutation in Patient 1 (p.Val487Gly) was previously reported in a cohort of 15 patients with other BRAF mutations. Although, individual phenotypes were not discussed, all patients had severe developmental delay, 13 had congenital heart defects, and 6 patients had seizures [Narumi et al., 2007]. Similarly, no individual clinical data are reported for two patients from Japan with this mutation [Abe et al., 2012]. The BRAF mutation in Patient 2 (p.Gln257Arg) has been described frequently. Three patients from Japan shared failure to thrive, severe developmental delay, and congenital cardiac anomalies (two with pulmonic stenosis and one with atrial septal defect) [Niihori et al., 2006]. Long-term data available at ages 19–23 years for four patients with this mutation showed severe intellectual disability in all (including one who was bedridden), seizures in three, pulmonic stenosis in one and abnormal brain MRI in two patients (cortical atrophy and ventricular dilation) [Abe et al., 2012]. The mutation in Patient 3 (MAP2K1p.Val60Gly) remains a novel mutation according to the clinical testing laboratory and our review of the literature. However, as neither of her parents carried this mutation, it is likely pathogenic causing the features of CFC in this patient. Narumi et al. [2007] described a novel MAP2K2p.Lys61Glu mutation in a patient with CFC, which is the same mutation found in Patient 4, but did not publish a description of the phenotype or clinical course.

Significant hyponatremia requiring sodium supplementation was a complication in three patients and has not been previously reported in CFC. The brief duration of hyponatremia in Patient 4 may be attributed to the use of diuretics for pulmonary edema. However, the hyponatremia in Patients 1 and 3 first occurred while they were on full enteral feeds, off of diuretics or intra-venous fluids, and relatively clinically stable. The hyponatremia could be influenced by prematurity, which can be associated with renal sodium loss from immature kidneys or inappropriate fluid retention in the neonatal period. The hyponatremia recurred in Patient 3 while she was critically ill and recurred in Patient 1 with the initiation of diuretics for severe systemic hypertension. Although, the persistence of hyponatremia into later childhood requiring significant supplementation, as seen in Patient 1, may be influenced by the diuretics for his severe systemic hypertension, other mechanisms may also play a role. Hyponatremia as a result of renal sodium wasting has been reported in one neonatal case of Costello syndrome [Lo et al., 2008]. Neither of our patients with recurrent hyponatremia had elevated urine sodium levels with normal sodium intake. Other possible causes of hyponatremia could be fluid retention, as suggested by the increased urine osmolality compared to serum osmolality, or increased enteral losses of sodium through poor absorption, although, the medical records do not mention abnormal stooling patterns. No further laboratory studies beyond the neonatal period were performed in Patient 1, whose hyponatremia later recurred in later infancy.

Three patients had severe respiratory complications, with two eventually requiring tracheostomy. Severe tracheolaryngomalacia and bronchomalacia requiring tracheostomy has been described in Costello syndrome [Digilio et al., 2008; Lo et al., 2008]. While prematurity may contribute, the evolution of the respiratory complications in these cases does not follow the expected time course of chronic lung disease from prematurity, as escalation of significant respiratory support was not seen until several months of age in two patients. Patient 3 had been weaned to minimal respiratory support on low flow nasal cannula oxygen supplementation and Patient 4 had already been discharged home on room air. Spontaneous pleural effusion, noted in these same two patients, has been described in Costello patients during the neonatal period [Digilio et al., 2008; Lo et al., 2008]. While chylothorax has previously been documented in CFC [Reynolds et al., 1986; Chan et al., 2002], the pleural effusion seen in Patient 3 was not a chylothorax, based on the pleural fluid studies obtained. No pleural fluid studies were done on Patient 4, whose pleural effusion spontaneously resolved after initiation of diuretics.

Significant systemic hypertension requiring pharmacological treatment, seen in two patients, has not previously been reported in CFC. Renal ultrasounds for both patients detected hydronephrosis, but renal vascular study was normal in Patient 1. Patient 3 had no renal vascular study. Premature infants may be at risk for developing systemic hypertension due to reduced nephron number or due to chronic lung disease, although, many cases resolve over the first 6 months of life [Seliem et al., 2007]. While Patient 3 died at age 4 months, Patient 1 still required multiple anti-hypertensive medications for systemic hypertension at age 6 years.

In addition to prematurity, the prenatal course of Patient 1 was also potentially complicated by gestational diabetes type A1. The severity of the gestational diabetes was unknown due to poor prenatal care but the newborn did not have hypoglycemia, which is a common neonatal presentation in infants of poorly controlled diabetic mothers. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in infants of diabetic mothers is typically present immediately after birth and is not progressive, in contrast to the natural history described in many of the rasopathies. Hypertension and hyponatremia are also not typically described in infants of diabetic mothers.

Sparse, loose or brittle hair, such as that seen in Patient 4, has previously been described in CFC and other rasopathies [Reynolds et al., 1986; Gripp et al., 2007; Rauen, 2007]. Specifically, loose anagen hair has been reported in the Noonan syndrome-like disorder associated with a recurrent SHOC2 mutation (p.Ser2Gly) [Mazzanti et al., 2003; Cordeddu et al., 2009]. Our report includes the first microscopic documentation of loose anagen hair in CFC (Fig. 1). We conclude that loose anagen hair may not be specific to any one rasopathy disorder.

The CFC phenotype also includes central nervous system abnormalities such as ventriculomegaly, hydrocephalus, and cortical atrophy. One report [Papadopoulou et al., 2011] recommends that all suspected CFC patients undergo brain MRI. This was performed for only two of our four patients, one of which was abnormal, with a communicating hydrocephalus after neonatal IVH and periventricular leukomalacia. Progressive microcephaly in Patient 1 may be the result of brain atrophy, but no further imaging has been performed after infancy.

Due to the significant overlap in prenatal findings, phenotypic features, and complications, differentiating between the rasopathies can be difficult in the neonatal period. Prematurity may also make some of the physical characteristics of CFC less obvious, especially if the premature infant requires respiratory support it may further obscure facial features during examination. Cutaneous findings may also not be present in the neonatal period. A history of polyhydramnios, with or without cystic hygroma, and the presence of generalized edema or redundant nuchal skin in the newborn, should lead to consideration of a Ras–MAP kinase pathway disorder. Further evaluation should include echocardiogram, renal ultrasound, and ophthalmology examination. We additionally recommend close follow-up of electrolytes, blood pressure, pulmonary function, and an awareness of possible extra-vascular fluid shifts, and potential for sudden deterioration after the neonatal period. Furthermore, we agree with previously published recommendations that brain MRI be performed to assess for intra-cranial abnormalities, which may require close monitoring or neurosurgical intervention [Papadopoulou et al., 2011]. Molecular testing may be helpful to confirm a specific diagnosis and enable the physician to anticipate potential complications and offer long-term prognosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Karen Thompson, MD, for her assistance in providing the pathologic examination and images for the hair sample for Patient 4. We would also like to acknowledge the patients and their families, as well as the staff at Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children who were involved in their care.