The impact of cardiac surgery in patients with trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 in Japan†

How to Cite this Article: Maeda J, Yamagishi H, Furutani Y, Kamisago M, Waragai T, Oana S, Kajino H, Matsuura H, Mori K, Matsuoka R, Nakanishi T. 2011. The impact of cardiac surgery in patients with trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 in Japan. Am J Med Genet Part A 155: 2641–2646.

Abstract

Congenital heart defects (CHD) are very common in patients with trisomy 18 (T18) and trisomy 13 (T13). The surgical indication of CHD remains controversial since the natural history of these trisomies is documented to be poor. To investigate the outcome of CHD in patients with T18 and T13, we collected and evaluated clinical data from 134 patients with T18 and 27 patients with T13 through nationwide network of Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery. In patients with T18, 23 (17%) of 134 were alive at this survey. One hundred twenty-six (94%) of 134 patients had CHDs. The most common CHD was ventricular septal defect (VSD, 59%). Sixty-five (52%) of 126 patients with CHD developed pulmonary hypertension (PH). Thirty-two (25%) of 126 patients with CHD underwent cardiac surgery and 18 patients (56%) have survived beyond postoperative period. While palliative surgery was performed in most patients, six cases (19%) underwent intracardiac repair for VSD. Operated patients survived longer than those who did not have surgery (P < 0.01). In patients with T13, 5 (19%) of 27 patients were alive during study period. Twenty-three (85%) of 27 patients had CHD and 13 (57%) of 27 patients had PH. Atrial septal defect was the most common form of CHD (22%). Cardiac surgery was done in 6 (26%) of 23 patients. In this study, approximately a quarter of patients underwent surgery for CHD in both trisomies. Cardiac surgery may improve survival in selected patients with T18. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Trisomy 18 (T18) and trisomy 13 (T13) represent common and important chromosomal disorders with multiple congenital anomalies. The incidence of T18 is estimated to 1/3,600–8,500, and that of T13 is estimated to be 1/10,000–20,000 [Carey, 2010]. Congenital heart defects (CHD) are present in about 80% of children with T13 and 90% of children with T18 [Carey, 2010]. Large systemic to pulmonary shunt lesions are common defects, and polyvalvular disease and mitral atresia are characteristic, especially in T18. Progressive pulmonary vascular obstructive change was observed in autopsy cases of T18 as early as 2-month old [Van Praagh et al., 1989].

These trisomies are also associated with multiple extracardiac defects, severe growth failure and developmental delay and only 5–10% survived beyond the first year [Rasmussen et al., 2003; Jones, 2006; Carey, 2010]. In a population-based study from the Northern region of England, the most common mode of death in patients with T18 and T13 was reported to be central apnea [Wyllie et al., 1994; Embleton et al., 1996]. The authors stated that cardiac surgery could not be justified in patients with T18 and those with T13. Even if survival occurs beyond the first year of life, patients with T18 and T13 frequently have marked developmental delay and respiratory and/or feeding problems that require intensive daily care. Therefore, surgical treatment for CHD in these patients has been limited even though their heart defects were expected to be successfully repaired from a view point of hemodynamics.

Recently, Kosho et al. [2006] showed improved survival of patients with T18 under intensive care including respiratory support, cardiac inotropic agents, and gastrointestinal surgery. Although they did not perform cardiac surgery in any of those patients, 25% of patients with T18 survived 1 year. Moreover, Graham et al. [2004] evaluated the outcome of cardiac surgery in 35 patients with T18 and T13, through data from the Pediatric Cardiac Consortium (48 centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe). They showed that 91% discharged alive and the patients without an extended preoperative ventilator requirement did not require prolonged mechanical ventilation after surgery [Graham et al., 2004]. Kaneko et al. [2008] compared outcomes of three distinct periods with different management: the first period, both pharmacological ductal intervention and cardiac surgery withheld; the second period, only pharmacological ductal intervention offered; the third period, both strategies available. The median survival time was significantly longer in the third (243 days), than the first (7 days) and the second (24 days). Kaneko et al. [2009] subsequently reported the outcome of 17 patients with T18 who underwent cardiac surgery including 11 having palliative surgery without cardiopulmonary bypass, 4 having palliative surgery followed by intracardiac repair (ICR), and 3 having primary ICR. Their survival time ranged from 12 to 1,384 days (median, 324 days), and 14 (82%) of them were discharged home with improved symptoms. However, it remains unclear whether cardiac surgery could affect their natural history and improve their lifespan because of lack of the large-scale follow-up study.

In order to accumulate further clinical evidence and determine the operative outcome of CHD in patients with T18 and T13, we performed a nationwide survey and analyzed clinical data, especially cardiac surgery and the outcome in these trisomies.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between July, 2005 and March, 2008, questionnaires made by the Committee for Genetics and Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases in the Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery were sent to affiliated hospitals that belonged to this nationwide network. The questionnaires included outcome at survey, genotype, birth weight, gestational age, parental age at birth, family history, cardiac phenotype, coexistence of pulmonary hypertension (PH), type of cardiac surgery, age at surgery, operative outcome, and extracardiac phenotype of patients with T18 and T13 diagnosed and followed at those hospitals. One hundred thirty-four patients with T18 and 27 patients with T13 were registered from 15 of 98 (15%) hospitals with neonatal intensive care units and analyzed in this surveillance. No patient was excluded in spite of incomplete answers.

Group comparison for mean difference was analyzed by Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. Associations between survival and various anomalies were estimated by Fisher's exact probability test. Logrank test was used to detect the difference of survival rate using Kaplan–Meier method between operated and non-operated patients. A P-value less than 5% was defined as statistically significant. These statistical analyses were performed using Statcel (OMS, Tokorozawa, Saitama).

RESULTS

General information of patients analyzed in this study is shown in Table I. Female patients were predominant in those with T18 (female to male ratio: 1.9) consistent with previous reports [Jones, 2006]. The results of karyotyping were reported in 41 patients with T18 and 12 patients with T13. Extracardiac anomalies were shown in Table II. Cerebellar hypoplasia and gastrointestinal defects including esophageal atresia and hepatoblastoma were characteristic anomalies in patients with T18.

| Trisomy 18 | Trisomy 13 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 134 (M 46, F 86, UK 2) | 27 (M 11, F 15, UK 1) |

| Median age at survey (range) | 4.8 months (0 day–19.9 years) | 3 months (0 day–9.0 years) |

| Median birth weight (range) | 1,692 g (650–2,698 g) | 1,976 g (664–2,620 g) |

| Median gestational age (range) | 37 weeks (28–42 weeks) | 36 weeks (26–40 weeks) |

| Median maternal age at birth (range) | 34 years (21–45 years) | 32 years (24–44 years) |

| Median paternal age at birth (range) | 36 years (21–50 years) | 38 years (25–50 years) |

- M, male; F, female; UK, unknown.

- Unknown sex: 2 (1.5%) of 134 in trisomy 18 and 1 (3.7%) of 27 in trisomy 13.

- Unknown genotype: 93 (69%) of 134 in trisomy 18 and 15 (56%) in trisomy 13.

| Trisomy 18 (n = 134) | Trisomy 13 (n = 27) |

|---|---|

| Overlapping finger 111 (83%) | Cleft palate/lip 15 (56%) |

| Cerebellular hypoplasia 79 (59%) | Polydactyly 10 (37%) |

| Esophageal atresia 13(10%) | Umbilical hernia 4 (15%) |

| Hepatoblastoma 3 (2%) |

Overall Outcome of Patients With Trisomy 18

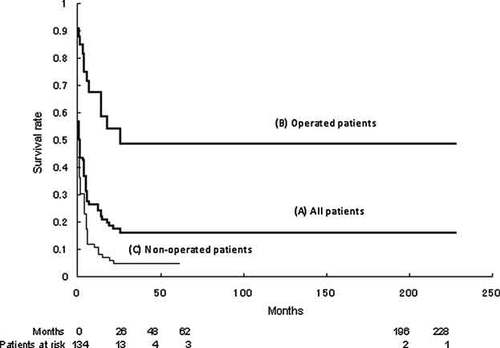

Twenty-three patients (17%) of 134 analyzed patients with T18 were alive at this survey (5 males and 18 females). Median age of surviving patients was 2.4 years ranging from 1 month to 19.9 years old. Three (13%) of these 23 patients had mosaicism of T18 and their ages were 3 years and 9 months, 16 years, and 19 years. One hundred five patients (78%) of 134 patients with T18 died at the median age of 3.6 months (40 males and 65 females) and 2 of them (1.9%) who died at 24 days and a year and 11 months old age showed mosaicism of T18. Outcomes of the remaining 6 patients were not reported. The vast majority of patients expired within 12 months as shown in Figure 1A. Although about 25% (survival rate 0.25) of patients with T18 survived the first year, the survival rate remained as high as 0.14 after 1 year, suggesting the relatively better survival in the subsequent years than in the first year (Fig. 1A). The median birth weight of patients who survived was significantly higher than expired patients with T18 (1,923 g in surviving patients vs. 1,701 g in expired patients, P = 0.032). Median gestational age of patients who survived was significantly longer than expired patients (39 weeks in survived patients vs. 37 weeks in expired patients, P < 0.01). The cause of the death was reported in 97 deceased patients (Table III). Thirty-eight patients (39%) of them were reported to die from respiratory failure, including 10 patients diagnosed with central apnea. Twenty-seven (71%) of the 38 patients died during the neonatal period. Cardiac involvement caused death in 25 patients from heart failure (26%) and 12 patients from arrhythmia (12%). Sudden death was also observed in 15 patients (15%). It is a remarkable finding that 6 of 15 patients died suddenly after successful cardiac surgery. Gastrointestinal defects did not significantly affect survival of T18 compared to those without gastrointestinal defects in this survey (P = 0.37).

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve of patients with trisomy 18. The survival rate of trisomy 18 remarkably declined after 26 months (A). Patients with cardiac surgery (B) survived significantly longer than those without cardiac surgery (C, P < 0.01).

| Trisomy 18 (n = 97) | Trisomy 13 (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure | 38 (39%) | 4 (25%) |

| Heart failure | 25 (26%) | 5 (31%) |

| Arrhythmia | 12 (12%) | |

| Sudden death | 15 (15%) | 3 (19%) |

| Unknown | 7 (7%) | 4 (25%) |

Congenital Heart Defects in Patients With Trisomy 18

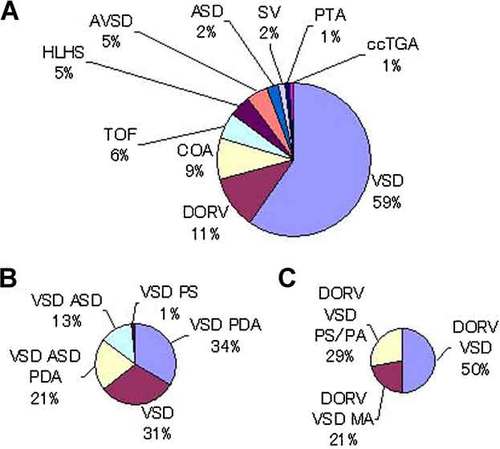

One hundred twenty-six (94%) of 134 patients with T18 had CHD. Details of CHD in T18 were shown in Figure 2A. Ventricular septal defect (VSD) was the most common form of CHD up to 75 patients (59%) with T18 and 68% of those with VSD had other pulmonary-systemic shunts, such as atrial septal defect (ASD) and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA; Fig. 2B). Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) was the second most common CHD found in 14 (11%) of 126 patients and 73% of them did not have pulmonary stenosis resulting in excessive pulmonary flow. Three cases of mitral atresia with DORV (21%) were reported in 14 patients with DORV and T18 (Fig. 2C), which appeared to be characteristic CHD in T18 reported as previous autopsies [Van Praagh et al., 1989].

Details of congenital heart defects (A), ventricular septal defect (B), and double outlet right ventricle (C) in patients with trisomy 18. A: VSD is the most common congenital heart defect in trisomy 18. B: VSD is frequently accompanied with other left to right shunt lesions, such as ASD and PDA in trisomy 18. C: DORV with mitral atresia is characteristic in trisomy 18. VSD, ventricular septal defect; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; COA, coarctation of aorta; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; HLH, hypoplastic left heart; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; ASD, atrial septal defect; SV, single ventricle; PTA, persistent truncus arteriosus; ccTGA, congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PS, pulmonary stenosis; MA, mitral atresia; PS/PA, pulmonary stenosis/pulmonary atresia.

Sixty-five patients (52%) of 126 patients with CHD in T18 suffered from PH due to pulmonary-systemic shunt lesion. Valvular disease was identified 58 (46%) of 126 patients with T18, including 33 multiple valvular lesions. Fourteen patients showed both atrioventricular and semilunar valvular defects.

Cardiac Surgery in Patients With Trisomy 18

Cardiac surgery was performed in 32 (25%) of 126 CHD patients with T18. Postoperative survival was observed in 18 (56%) of 32 operative cases at this survey. Postoperative periods of these survivors were ranged from 2 to 216 months. The remaining 14 patients died after surgery and 2 of them died within 1 month after surgery. The median age at surgery was 1.8 months of age ranging from 1 day to 18.6 months of age. Fourteen (61%) of 23 patients with palliation and 2 (40%) of 5 patients with intracardiac surgery were alive at this survey (Table IV). Two patients were received two-staged surgery (palliative repair followed by ICR) and one of them survived. The complex heart lesions such as hypoplastic left heart (HLH), single ventricle, and persistent truncus arteriosus (PTA), and congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries were not operated in this study. Thirty (93%) of 32 operated patients manifested PH before surgery, which was improved after cardiac surgery in 17 patients of them (57%). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were illustrated for operated and non-operated patients with T18 (Fig. 1B,C). The survival estimate of those who were operated (Fig. 1B) was significantly higher than of those who were not operated (Fig. 1C) in this T18 cohort (P < 0.01). Although the vast majority of patients with T18 were not operated in this study, the longest observational period of non-operated patients was 62 months, which was much shorter than that of operated patients.

| CHD | Operation | Survival | Procedure (number) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VSD | 13 | 7 | PAB (10) ICR (1) UK (2) |

| VSD PDA | 8 | 4 | PAB + DL (7) ICR (1) |

| VSD PDA ASD | 2 | 1 | UK (2) |

| VSD PAPVC | 2 | 1 | ICR (1) ICR + PVR (1) |

| COA VSD | 4 | 2 | PAB + COR (3) ICR (1) |

| DORV VSD PS | 1 | 1 | CS (1) |

| DORV VSD MA COA AS | 1 | 1 | PAB (1) |

| TOF | 1 | 1 | BTS (1) |

| Total | 32 | 18 |

- CHD, congenital heart defects; VSD, ventricular septal defect; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; ASD, atrial septal defect; PAPVC, partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection; COA, coarctation of aorta; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; PS, pulmonary stenosis; MA, mitral atresia; AS, aortic stenosis; PAB, pulmonary artery banding; ICR, intracardiac repair; UK, unknown; DL, ductus ligation; PVR, pulmonary vein repair; COR, coarctation of aorta repair; CS, central shunt; BTS, Blalock-Taussig shunt.

Overall Outcome of Patients With Trisomy 13

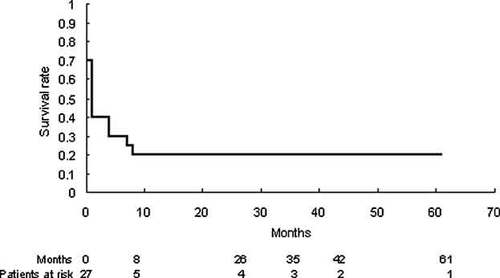

Five (19%) of 27 patients with T13 were alive at this survey (4 males and 1 female). The complex heart defects such as HLH and PTA were not operated. The median age of surviving patients was 3.5 years of age ranging from 0 day to 5.1 years old. Sixteen (59%) of 27 patients were deceased (3 males, 12 females, and 1 unknown gender) and the median age of death was 1 month. Mosaicism of T13 was reported in 1 surviving patient (20%) and 1 expired patient (6.3%). Congenital anomalies except heart were listed in Table II. Kaplan–Meier survived curve was illustrated in Figure 3 showing that the vast majority of them were dead within the first year. The cause of death of patients with T13 included heart failure (31%), respiratory failure (25%), and sudden death (19%; Table III).

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve in patients with trisomy 13. The survival rate of trisomy 13 remarkably declined after 8 months.

Congenital Heart Defects and Cardiac Surgery in Patients With Trisomy 13

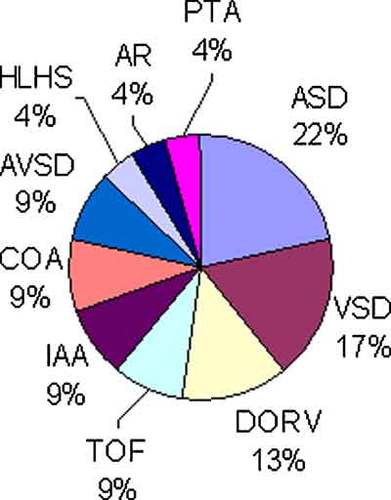

Twenty-three (85%) of 27 patients with T13 had CHD. ASD was the most common CHD found in 5 cases (22%) followed by VSD in 4 cases (17%), and DORV in 3 cases (13%) as shown in Figure 4. Two of 3 patients with DORV were accompanied with pulmonary atresia. Thirteen (57%) of 23 CHD were accompanied by PH.

Details of congenital heart defects in patients with trisomy 13. ASD was the most common congenital heart defect in patients with trisomy 13. Most of DORV accompanied with excess pulmonary blood flow. ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; IAA, interruption of aortic arch; COA, coarctation of aorta; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; AR, aortic regurgitation; PTA, persistent truncus arteriosus.

Six (26%) of 23 patients received cardiac surgery and half of them (50%) were alive at the time of this survey. Age at surgery was distributed between 4 days and 9.5 years. Three (50%) of the 6 operated patients had PH, which improved after surgery. Six surgical procedures included three palliations (50%), along with 2 (67%) surviving and 2 ICR (33%) with 1 (50%) surviving (Table V).

| CHD | Operation | Survival | Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| VSD ASD PDA | 1 | 1 | PAB + DL (1) |

| ASD PDA | 1 | 0 | UK (1) |

| AVSD PDA | 1 | 1 | ICR (1) |

| COA VSD PDA | 1 | 1 | PAB + DL (1) |

| IAA APW VSD | 1 | 0 | ICR (1) |

| TOF | 1 | 0 | BTS (1) |

| Total | 6 | 3 |

- CHD, congenital heart defects; VSD, ventricular septal defect; ASD, atrial septal defect; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PAB, pulmonary artery banding; DL, ductus ligation; UK, unknown; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; ICR, intracardiac repair; COA, coarctation of aorta; IAA, interruption of aortic arch; APW, aortopulmonary window; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; BTS, Blalock-Taussig shunt.

DISCUSSION

In order to delineate the current situation of cardiac surgery in patients with T18 and T13, we performed the nationwide survey through the network of Japanese Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery. In our study, 94% of T18 and 85% of T13 had CHD. The vast majority of CHD had left to right shunt lesions and excessive pulmonary blood flow, which probably resulted in PH that was observed in 52% of patients with T18 and in 57% of those with T13, respectively. Twenty-six percent of patients with both trisomies received surgery for CHD and only 2 of 32 patients died in perioperative period in T18. It is noteworthy that operated patients survived significantly longer than non-operated patients in patients with T18 (Fig. 1B,C), although it is possible that operated patients had simple CHD and/or less extracardiac problems. As for patients with T13, our data collection was not detailed enough to analyze the surgical impact on their survival. In our limited data, operative survival rate of T13 seemed not inferior to that of T18, suggesting that cardiac surgery may be tolerated in at least some patients with T13. Recently, there is a growing tendency to take cardiac surgery into consideration in both trisomies according to clinical status despite the poor life expectancy [Carey, 2005, 2010; Jones, 2006]. This trend has probably been growing in the background of patients' support groups, general respect for parental autonomy, and accumulation of clinical evidence such as long-term survivors and effectiveness of intensive treatment [Graham et al., 2004; Kosho et al., 2006; Kaneko et al., 2008, 2009]. Our nationwide survey supports this trend providing information from relatively large numbers of patients with T18 and T13.

With regard to surgical procedures in patients with T18 and T13, it is debatable whether an intracardiac repair using cardiopulmonary bypass or a palliative repair should be employed for operative survival. In our study, about 20–30% of patients received ICRs and half of them survived postoperatively in both trisomies, although majority of patients underwent palliative repairs (Tables IV and V). Kaneko et al. [2009] reported better postoperative survival with palliative repairs than primary ICRs among 17 patients with T18 who had life-threatening extracardiac problems. On the other hand, Van Dyke and Allen [1990] reported a T18 patient with VSD and PDA who survived for more than 5 years after ICR. Graham et al. [2004] also reported that 32 (91%) of 35 patients with T18 and T13 who underwent cardiac surgery were discharged from hospitals alive. Their primary surgical procedures included 18 ICRs, 13 palliative repairs as well as 4 PDA ligations, suggesting that palliative surgery such as pulmonary artery banding (PAB) might not be always indicated as a primary repair to alleviate the risk of surgery [Graham et al., 2004]. This series included four patients with VSD who underwent ICRs after PAB. Teraguchi et al. [1998] also described two patients with T18 and large VSD who survived after the ICR following PAB. It should be also noted that all studies described above excluded intracardiac surgery for complex type of CHD, such as HLHS.

Our study was based on questionnaires about CHD and extracardiac anomalies and had limitation for the assessment of clinical severity of each patient. We could not recruit all patients with T18 and T13 because of partial response (15% of affiliated hospitals) to our survey. We might have missed patients who died earlier, resulting in increased survival or surgical success rate. The vast majority of patients died by 26 months in T18 and 8 months in T13, reflecting the short life expectancy. On the other hand, a small number of patients at risk may overestimate the survival rate of both trisomies as no death seemed to occur thereafter (Figs. 1 and 3). Hence, this study may be defined as a multi-institutional observation with some bias rather than as a population-based analysis.

Because no well-defined criteria for cardiac surgery are available for patients with T18/T13, the indication of operation was completely dependent on each physician's decision, and we did not know how physicians struggled and finally decided to operate on patients with T18 and T13. Although our study suggested that operated patients survived longer than non-operated patients with T18, general postoperative survival of simple CHD including VSD, ASD, and PDA should reach more than 99% in nonsyndromic patients, whereas it declined as low as 50% in both trisomies in this study. Even though cardiac surgery successfully corrected abnormal hemodynamics, non-heart-related death could be encountered in T18 and T13 (Table III). Respiratory failure including central apnea may not be avoided in these trisomies regardless of outcomes of cardiac surgery. Unexpected or sudden death was also reported, which might be related to apnea. On the other hand, it was evident that some patients with T18 and T13 could survive and discharge hospital [Carey, 2010]. Technical difficulties in performing surgical treatment of relatively simple CHD in patients with T18/T13 are being overcome and cardiac surgery could be considered in those without severe extracardiac problem.

In this study, although we analyzed the impact of cardiac surgery on survival, we could not evaluate the impact of cardiac surgery on indices concerning quality of life such as hospital discharge rate, rate of home mechanical ventilation, rate of home oxygen therapy, rate of oral feeding without nasal tube. It is important to evaluate how well the patients become after cardiac surgery in future studies.

CONCLUSION

Cardiac surgery for CHD was performed in a quarter of patients with T18 and T13 and resulted in better life outcome, especially in T18, in the nationwide survey in Japan. The indications of cardiac surgery for these patients need to be considered electively from the individual patient's status along with continuous support for decision-making by the parents. It is still not clear whether cardiac surgery improves the long-term prognosis of patients with T18 and T13; however, cardiac surgery may be indicated for patients with relatively simple CHD and/or extracardiac complications. We believe that the opinions of parents of patients should be strongly respected in determining whether such surgery is performed. Physicians should provide information to the family sufficient to enable optimal decision-making. Pediatric cardiologists as well as clinical geneticists need not only to perform counseling and respect parent's decision, but also address the opinions as professionals based on medical experience, knowledge, and ethics.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the following institutions and investigators collaborated in this study: Kyusyu Kousei Nenkin Hospital: K. Jo-o; Saitama Medical University International Medical Center: M. Taketatsu; Japanese Red Cross Medical Center: H. Yoda; Tokyo Metropolitan Kiyose Children's Hospital: H. Ohki; Chiba Children's Hospital: H. Nakajima; Toyama University Hospital: F. Ichida; Nagano Children's Hospital: K. Takigiku; Kanazawa Medical University Hospital: E. Koh; Kyusyu University Hospital: K. Furuno; Fukuoka Children's Hospital and Medical Center for Infectious Disease: N. Fusazaki; Aichi Children's Health and Medical Center: T. Yasuda. We would also like to thank the following members in the Committee for Genetics and Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease in the Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery: Y. Aragaki, K. Ogawa, Y. Ono, K. Koyama, K. Kuroe, T. Kobayashi, I. Shiraishi, M. Nakagawa, Y. Nomura, Y. Hayabuchi, T. Murakami, S. Yasukouchi, T. Yasuda.