Congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, and epidermal nevi (CLOVE) syndrome: CNS malformations and seizures may be a component of this disorder†

How to cite this article: Gucev ZS, Tasic V, Jancevska A, Konstantinova MK, Pop-Jordanova N, Trajkovski Z, Biesecker LG. 2008. Congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, and epidermal nevi (CLOVE) syndrome: CNS malformations and seizures may be a component of this disorder. Am J Med Genet Part A 146A:2688–2690.

Abstract

A newborn girl was found to have a massive lymphatic truncal vascular malformation with overlying cutaneous venous anomaly associated with overgrown feet and splayed toes. These manifestations comprise the recently described CLOVE syndrome. She also had cranial asymmetry and developed generalized seizures, which were treated with anticonvulsants. Cranial CT showed encephalomalacia, widening of the ventricles and the sulci, hemimegalencephaly (predominantly white matter) and partial agenesis of corpus callosum. Review of the literature identified several other patients with CLOVE syndrome, some of whom were misdiagnosed as having Proteus syndrome, with strikingly similar manifestations. We conclude that CNS manifestations including hemimegalencephaly, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, neuronal migration defects, and the consequent seizures, may be an rarely recognized manifestation of CLOVE syndrome. © 2008 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

CLOVE syndrome is a recently delineated disorder that comprises vascular malformations (typically truncal), dysregulated adipose tissue, scoliosis, enlarged bony structures (typically of the legs) without progressive or distorting bony overgrowth [Sapp et al., 2007]. This recent delineation distinguishes it from Proteus syndrome, a disorder that comprises localized, progressive, postnatal overgrowth with bony distortion, dysregulated adipose tissue, cerebriform connective tissue and linear epidermal nevus, hemimegalencephaly, and other manifestations [Biesecker et al., 1999; Turner et al., 2004; Biesecker, 2006]. We describe a neonate with features of CLOVE syndrome and hemimegalencephaly with agenesis of the corpus callosum, features not included in the previous description of CLOVE syndrome.

CLINICAL REPORT

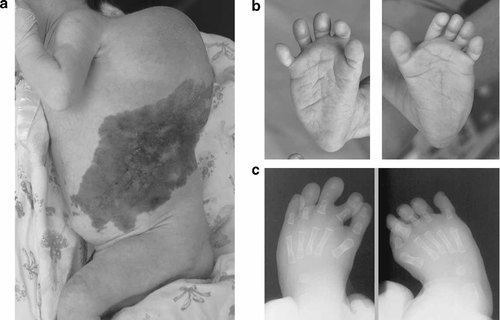

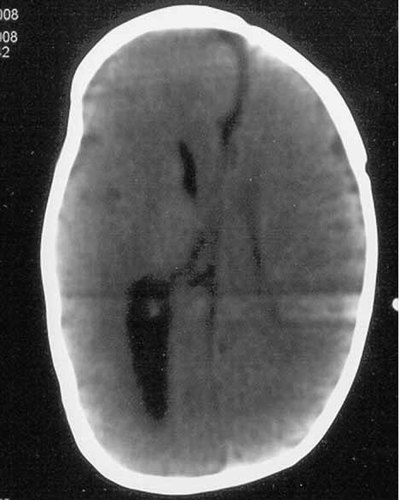

A 15-day-old Caucasian girl was the first child of nonconsanguineous and otherwise healthy and young parents. At the end of the third trimester an abdominal wall mass was noted on ultrasound examination. She was delivered by cesarean at 31 weeks gestation, with an Apgar score of 7/8. Her birth weight was 3,660 g (≫97th centile), her length was 50 cm (∼90th centile) and her OFC was 36 cm (≫97th centile). She had downslanting palpebral fissures, flattening of the malar bones, relative lengthening of the face, and a persistently open mouth. There was an asymmetry of the face, with the left facial area being enlarged. Ptosis, horizontal nystagmus, and bilateral cataracts were also noted. She had massive overgrowth of the left lateral truncal region with overlying vascular malformations, including fragile, superficial vascular blebs (Fig. 1A). Mid-abdominally there was a smaller mass of a similar nature. Moderate to severe macrodactyly of the feet was present, with widening anteriorly and splaying of the digits (Fig. 1B,C). A chromosomal analysis from peripheral blood was normal, 46,XX (400 band resolution). Cranial CT showed left-sided hemimegalencephaly (predominantly white matter) and partial agenesis of corpus callosum (Fig. 2). Thoracic CT showed large cystic structures, consistent with lymphatic vascular malformations. Chronic, generalized convulsions developed and were treated with anticonvulsants. At this writing the child is 3 months old.

A: The patient at 15 days of age, with a massive subcutaneous truncal overgrowth with overlying vascular malformation. B: The overgrowth of her right and left feet, respectively, with splaying of the digits. C: Plain radiographs of the feet show normal bony architecture, in contrast to the disorganized architecture of Proteus syndrome.

Her cranial CT shows encephalomalacia, enlarged ventricles and sulci, hemimegalencephaly (predominantly white matter), and partial agenesis of corpus callosum.

DISCUSSION

The most striking features in this patient were the massive truncal vascular malformation and the overgrown feet. This combination of anomalies has been provisionally designated as CLOVE syndrome, to indicate that it comprises Congenital Lipomatous Overgrowth, Vascular malformations, and Epidermal nevi [Sapp et al., 2007]. While both CLOVE syndrome and Proteus syndrome can manifest overgrowth, lipomas, epidermal nevi, vascular malformations, there are a number of differences that allow CLOVE to be readily distinguished. In CLOVE syndrome the overgrowth is congenital, of a “ballooning” nature, grows proportionately with the patient, and typically affects both feet. In Proteus syndrome, there is typically no overgrowth at birth, the overgrowth is distorting and disproportionate, and the overgrowth is strikingly asymmetric. PTEN gene mutations were not found in the seven patients described with CLOVE syndrome [Sapp et al., 2007]. In addition, to our best knowledge the PTEN mutation was not found in any single bona fide case of Proteus syndrome [Barker et al., 2001]. Other diagnoses that should be considered in a child with asymmetric overgrowth include Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, Ollier disease, Bannayan-Riley-Zonana syndrome, Maffucci syndrome, encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis [Rizzo et al., 1993], and the elattoproteus syndrome (the inverse of PS) [Happle, 1999]. We conclude that this patient has CLOVE syndrome, in spite of her having several features not reported in that disorder [Sapp et al., 2007].

The identification of these atypical features provide an opportunity to expand our understanding of CLOVE syndrome. The ocular features in the present patient included ptosis, horizontal nystagmus, and bilateral cataracts and all three of these manifestations have been associated with Proteus syndrome [De Becker et al., 2000; Sheard et al., 2002; Turner et al., 2004]. These findings have not been reported with CLOVE syndrome, and we suggest that they may be uncommon manifestations of this disorder.

She also had partial agenesis of corpus callosum together and marked left-sided hemimegalencephaly with evidence of a neuronal migration defect. This apparent CNS dysgenesis manifested as seizures, which were successfully controlled with anticonvulsants. It is too soon to know if these CNS findings will also be associated with developmental handicaps in this patient. Patient 1 reported by Sapp et al. 2007 had CNS anomalies, demonstrated by MRI to include polymicrogyria, non-contiguous abnormalities of the gray and white matter, a four-layered cortex, and ventriculomegaly. He had EEG evidence of epileptic activity and died at the age of 9 weeks.

The hemimegalencephaly in the present patient led to an initial suspicion of the diagnosis of Proteus syndrome. CNS abnormalities are present in more than 40% of patients with confirmed Proteus syndrome and hemimegalencephaly is one of the most common manifestations [Turner et al., 2004]. However, hemimegalencephaly can be a manifestation of non-Proteus overgrowth disorders as well.

Partial agenesis of the corpus callosum has been claimed to be a manifestation of Proteus syndrome [McCall et al., 1992, case 2]. However, a critical review of the Proteus syndrome literature has suggested that case 2 of McCall et al. 1992 does not meet the current criteria for Proteus syndrome [Turner et al., 2004]. Interestingly, the non-CNS manifestations in the patient described by McCall et al. 1992 are strikingly similar to the present patient. These include a congenital truncal mass that was a mix of lymphatic elements with overlying venous vascular anomaly and bilaterally overgrown feet with splayed toes. We conclude that case 2 reported by McCall et al. 1992 had CLOVE syndrome. Hypoplasia of corpus callosum has also been suggested to be associated with Proteus syndrome by Griffiths et al. 1994. However, their diagnoses of Proteus syndrome are not supported by the current diagnostic criteria and the clinical data presented there do not allow another diagnosis to be made [Turner et al., 2004]. It is of note that the clinical separation of the two entities seems to be possible, but the molecular proof is still lacking for both syndromes. Taken together, these data suggest that neuronal migration defects, hemimegalencephaly, partial aplasia or agenesis of the corpus callosum with the attendant cognitive and convulsive manifestations may be a recognizable feature of the CLOVE syndrome.