Congenital vascular malformations: A series of five prenatally diagnosed cases†

How to cite this article: Connell F, Homfray T, Thilaganathan B, Bhide A, Jeffrey I, Hutt R, Mortimer P, Mansour S. 2008. Congenital vascular malformations: A series of five prenatally diagnosed cases. Am J Med Genet Part A 146A:2673–2680.

Abstract

In the literature there are single case reports of mediastinal/chest and limb combined vascular malformations (previously labeled “hemangiolymphangiomas”). A variable outcome in such prenatally diagnosed cases is reported. Presented here is the only series of patients reported with these macrocystic, predominantly lymphatic malformations. Prenatal ultrasound scan and post-mortem examination findings are described. In our experience the outcome has been poor and this highlights the dilemma faced by clinicians and parents when these lesions are diagnosed prenatally. We present a series of five, prenatally diagnosed vascular (combined vascular malformations and simple localized lymphatic malformations) malformations. Three cases had lower leg involvement with extension into the abdomen and two cases had lymphatic malformations of the chest wall with involvement of the upper limb(s). Management of a twin pregnancy, in which one twin was affected, is described. In two cases, termination of pregnancy was undertaken because of the extensive nature of the lesion. One case died in utero and one in the neonatal period. The fifth case is an 11-year-old boy, whose lower limb deformity illustrates the considerable morbidity associated with this condition. © 2008 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular malformations occur in approximately 0.3–0.5% of the population and lymphatic malformations make up a proportion of these lesions [Mulliken and Virnelli-Grevelink, 1999]. Problems with nomenclature, diagnosis and classification make the literature on vascular malformations and lymphatic anomalies confusing.

Mulliken and Glowacki 1982 and Mulliken 1993 clarified the situation by dividing vascular anomalies into two separate entities: vascular tumors (includes infantile hemangiomas) and vascular malformations. Establishing the distinction between vascular tumors and malformations was of importance as this classification system is widely recognized by experts in the field and the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies [Enjolras and Mulliken, 1997]. They described hemangiomas as having endothelial hyperplasia with rapid post-natal growth followed by slow involution. Vascular malformations were described as being characterized by flat endothelium and growth of lesion is commensurate with the individual [Cohen, 2006]. This classification has been extended into lymphatic anomalies. Therefore, histologically, lymphatic malformations have a single layer of endothelial cells and in theory a “lymphangioma” would need to demonstrate a post-natal proliferative phase, endothelial hyperplasia and an involutional phase, thus making it a theoretical equivalent to an infantile hemangioma [Cohen, 2006].

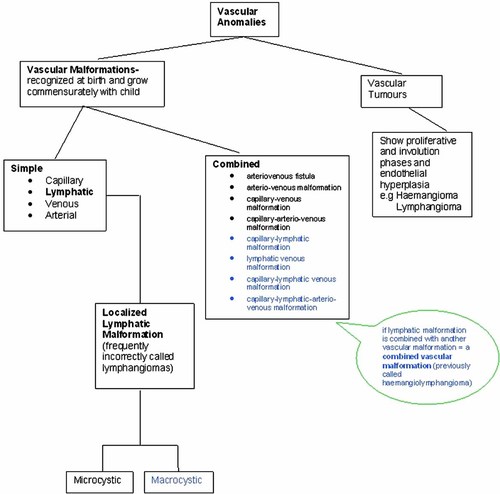

A primary lymphatic malformation is a developmental anomaly of the lymphatic system. These malformations can be simple, just involving lymphatic vessels or combined, involving more than one type of vasculature [Cohen, 2006; Garzon et al., 2007]. The diagram (Fig. 1) below (based on the Mulliken's classification described in 1996) has been developed to illustrate the classification system for vascular anomalies, focusing on the lymphatics. The lesions discussed in this article fall into the group highlighted in blue font (online issue is in color)—that is, the localized macrocystic lymphatic malformations and the combined vascular malformation (with lymphatic involvement) group. Historically, localized congenital lymphatic malformations have been called “lymphangiomas” [Garzon et al., 2007]. If blood vessels are involved within these lesions then the term “hemangiolymphangioma” was ascribed to what are now recognized as combined vascular malformations [Cohen, 2007].

Classification of vascular anomalies. (Diagram based on classification described by Enjolras and Mulliken, 1997). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Localized lymphatic malformations can be divided into macrocystic, or deep, and microcystic, or superficial lesions [Garzon et al., 2007]. Both types can be combined with other vascular malformations and the distinction between the two has implications for treatment and prognosis. Localized congenital lymphatic malformations can also be described based on anatomical location: 75% are located in the neck, 20% in the axillae, 2% intra-abdominal/retroperitoneal, 2% in limbs and bones and 1% in mediastinum [Anderson and Kennedy, 1992]. The patients in this series all had rare malformations because of the anatomical location of their lesions.

Histologically, these vascular malformations involving the lymphatics are non-malignant but the propensity to rapid growth and invasion and/or compression of surrounding tissues can have severe consequences. They tend to cause more distortion than other types of vascular malformations, and treatment of these lesions can be very problematic, depending on the other structures involved and because complete removal of all endothelial cells is not possible, regrowth of the lesion can occur following surgery [Cohen, 2006]. Prenatal diagnosis of some vascular malformations is feasible given the quality of imaging modalities available and regular scanning enables monitoring of the rate of growth of the lesions, an important factor when trying to assess the severity and prognosis of the anomalies. We report here on a series of five vascular malformations with detailed prenatal ultrasound images.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 24-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to the fetal medicine unit at 22 weeks gestation, having naturally conceived dichorionic twins. This was her first pregnancy and she had had a normal scan at 12 weeks. On the 22-week scan an extensive, largely external, cystic abnormality of the chest wall of one twin was identified. The lesion extended into both upper arms and into the mediastinum. A moderately sized pericardial effusion was also detected (see Figs. 2 and 3 for antenatal images). After full discussion with the parents they opted to continue the twin pregnancy until 32 weeks gestation and then have a selective termination of the affected fetus. The decision to wait until 32 weeks was made to optimize the chances of survival of the second twin, as selective termination at 22 weeks would have meant a substantial risk of loss of the unaffected fetus. The mother had 2-weekly scans to look for polyhydramnios and growth of the lesion and at 32 weeks a selective termination of the affected fetus was carried out. The mother went into spontaneous labor six days after the procedure and delivered both babies. A post-mortem examination was performed on the affected twin. The unaffected twin was born with no medical concerns.

Case 1: Longitudinal scan through the upper chest (left) and lower head (right) showing the mixed solid/cystic malformation extending from the lower neck to the abdomen. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Case 1: Cross-section through the fetal chest (heart uppermost right) showing the extent and relative size of the malformation at thoracic level. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

The post-mortem examination report confirmed a large localized lymphatic malformation with dilated lymphatic vessels infiltrating subcutaneous tissue and muscle of the right side of the trunk, right upper limb including the right hand, and to a lesser extent the left side of the trunk and left upper limb (Figs. 4 and 5). Due to the degree of autolysis the histology could not confirm whether the lesion also involved blood vessels. No other congenital anomalies were identified.

Case 1: Image from the post-mortem examination of the fetus (front view). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Case 1: Image from the post-mortem examination of the fetus (side view). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Case 2

A 37-year-old Caucasian woman in her first pregnancy was scanned at 22+3 weeks gestation and the fetus was found to have a cystic lesion arising from the left side of the chest wall and extending into the left axilla. The chorionic villus sampling karyotype was 46XY. Repeat scan at 28+3 weeks confirmed a septated macrocystic lesion. By 32 weeks gestation the lesion had enlarged and was extending from left side of neck down to the fetal pelvis, involving the whole of the left arm which had become edematous. Fetal MRI scan at 35 weeks gestation confirmed the above ultrasound scan findings. The mass was multiloculated and extended into the apex of the left thorax.

A male baby was born at term via an elective caesarian with Apgars of 3 at 1 min and 7 at 5 min. He was admitted to the neonatal unit, intubated and ventilated. He underwent a series of procedures in an attempt to treat the lesion: laser treatment, surgical debulking and sclerotherapy. At the age of 16 weeks he was discharged home from the neonatal unit. At the age of 5 months he developed a fever and the lesion showed a sudden increase in size (estimated to have doubled in size). He decompensated secondary to sepsis and despite full supportive care his condition deteriorated and care was withdrawn after consultation with the parents.

The post-mortem examination showed a large, cystic mass distorting the left side of the trunk and left upper arm. The lesion extended into the soft tissues of the mediastinum and neck, possibly causing esophageal or vascular compression. On histology, the lesion was composed of multiple, dilated lymphatic channels and congested small vessels with associated lymphoid aggregates. Areas of blood vessel proliferation were also present, as were occasional entrapped normal looking larger blood vessels, making this a combined vascular malformation. Multiple small areas of dilated lymph vessels were also present in the lungs. Syndactyly of II and IV digits of left hand and an absent right nipple were noted. No other congenital or structural abnormalities were identified. Cause of death was documented as septic shock (Pseudomonas isolated from blood culture), complicated by fluid sequestration into the malformation with subsequent cardiac failure.

Case 3

A 34-year-old Caucasian woman, gravida 4 para 2, was referred to the fetal medicine unit at 22 weeks gestation, due to detection of a swelling of the left fetal leg at the routine anomaly scan. She gave no significant medical, drug or family history and this pregnancy had been uncomplicated prior to the 22-week routine anomaly scan. Detailed ultrasonagraphy confirmed a multicystic swelling of the left leg and foot (Fig. 6). There was also evidence of loculated edema in the pelvis but no overgrowth (limb hypertrophy) of the left leg. Other structures appeared normal. Follow-up scans showed rapid expansion of the left leg and abdomen, in-keeping with an extensive combined vascular malformation. Parents opted for a termination of pregnancy at 23 weeks gestation, in view of the size and rapid growth of the lesion.

Case 3: Longitudinal section through the left leg showing the hip (right), foot (left) and the malformation extending around the shin and calf. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

A limited post-mortem examination was carried out. A male fetus, with a normal male karyotype was examined. Proliferation of lymphatic vessels involving the whole left lower limb, left buttock and wall of left side of the pelvis was reported. The left testicle was fibrotic, consistent with an old infarction, possibly due to previous vascular insufficiency as a result of the lymphatic proliferation. Histological appearance was one of predominantly abnormal lymphatic vessels but also a hemangiomatosis component. No other malformation or primary abnormality was found in the internal organs or skeleton. The photographs illustrate the formidable size and cystic nature of the lesion, with both lymphatic and blood vessel involvement (Figs. 7 and 8).

Case 3: Post-mortem examination image of the fetus, showing the malformation of the left leg (anterior view). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Case 3: Post-mortem examination image of the fetus, showing the malformation of the left leg (posterior view). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Case 4

A 29-year-old woman, with no significant medical or family history, in her first pregnancy, was scanned at 23+4 weeks gestation. The fetus was found to have enlargement of the left leg, extending from the foot up into left buttock and left side of the pelvis (level of lower pole of left kidney, although kidney not involved). It was most pronounced in the left thigh, which was very enlarged. Femur lengths on left and right were equal. No other structural abnormalities were identified. The severity of this anomaly was explained to parents, who opted to continue with the pregnancy. However, the female fetus died in utero at 28+3 weeks gestation.

Post-mortem examination confirmed the presence of a combined vascular malformation (lymphatic and venous vessel involvement) involving the subcutaneous tissues of the whole of the left lower limb, with extension into the left pelvic wall, left buttock and left retroperitoneal space (Fig. 9). There was no direct infiltration or involvement of any viscera. Histologically this large malformation was made up of abnormal, irregular and greatly dilated lymphatic vessels, embedded in edematous connective tissue. The lesion infiltrated skeletal muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Focally and largely at the edge of the mass, there were collections of abnormally formed venous vessels. An occlusive thrombus in the left common iliac artery and the lower aorta was deemed to be the cause of death. The precipitating factor for thrombus appeared to have been the vascular malformation, which whilst it did not infiltrate any major vessel walls, caused compression of the left common iliac artery. This compression would have resulted in abnormal blood flow, a risk factor for thrombosis even in the absence of any coagulopathy. No other congenital anomalies were identified on the post-mortem examination.

Case 4: Post-mortem examination image of fetus showing the malformation of the left leg, with extension into left buttock and pelvis (posterior view). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Case 5

This patient was referred to a national pediatric lymphedema clinic. He was seen age 12 years. He is the eldest of three sons, born to Sri-Lankan, non-consanguineous parents. It was reported that an abnormality of the right leg was detected on ultrasound scan at about 32 weeks gestation. No further details of scan findings are available as the antenatal care was undertaken in Denmark. He was born with an extensive combined vascular malformation of the right leg, with involvement of the right hind-quarter. His general health has been good and he has made normal developmental progress, although his gross motor skills have been impaired by the lesion of the right leg.

On examination he had an extensive abnormality of the right leg that exhibited both lymphatic and venous components (Figs. 10 and 11). Oozing lymph had caused dermatitis and the right foot was so edematous that the resulting deformity had created an amputated toe defect. Scars from previous surgical intervention were evident. The boy's mobility is restricted as a result of this abnormality and he uses calipers to walk. Clinically there was no limb length discrepancy of the right leg. An MRI angiography reports an extensive vascular malformation involving the whole of the right lower extremity, with extension into the pelvis. Bandaging treatment was offered as the initial management strategy in an attempt to reduce the degree of swelling and deformity caused by the associated lymphedema. The patient has had recurrent cellulitis in the right leg and amputation is being considered as a treatment option in view of the severity of morbidity caused by the malformation.

Case 5: Extensive combined vascular malformation of right leg. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Macroscopic image of the lymphatic anomaly in the right groin. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

DISCUSSION

Localized lymphatic malformations are developmental malformations of the lymphatic system. Combined vascular malformations involving the lymphatics (previously labeled hemangiolymphangiomas) are usually lymphatic-venous or lymphatic-capillary malformations [Senoh et al., 2001]. These malformations are considered to be isolated congenital anomalies rather than inherited ones and thus patients can be advised of a low recurrence risk in future offspring. This series of patients documents the correlation between prenatal ultrasound scan images, post-mortem examination findings and outcome in combined vascular malformations in rare anatomical locations. Table I summarizes the outcomes in this series of cases.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestation (in weeks) at presentation | 22 | 22 | 22+3 | 22 | 32 |

| Type of lesion | Combined vascular malformation | Combined vascular malformation | Combined vascular malformation | Predominantly lymphatic malformation | Combined vascular malformation |

| Outcome | Termination | Died age 5 months | Intrauterine death | Termination | Severe morbidity |

The following articles discuss combined vascular and localized lymphatic malformations under the rubric of “hemangiolymphangiomas” and “lymphangiomas” respectively. Single case reports of combined vascular malformations describe variable outcomes. Senoh et al. 2001 report successful outcome following sclerotherapy injection of a combined vascular malformation of the thorax. Tseng et al. 2002 report on a case with an axillary combined vascular malformation that was successfully excised. Okazaki et al. 2007 describe their experience of sclerotherapy and surgery in treatment of localized lymphatic malformations and found that sclerotherapy was not as effective as reported in the literature. Case 5, described above, illustrates the degree of physical deformity that these lesions can cause if they are not amenable to surgery or sclerotherapy. The psychological repercussions of such a physical deformity are enormous and should not be dismissed. Four cases of abdominal lymphatic malformations with extension into the leg have all been managed by termination of pregnancy [Kozlowski et al., 1988; Katz et al., 1992; Kaminopetros et al., 1997; Deshpande et al., 2001], as was an abdominal combined vascular malformation [Giacalone et al., 1993]. Schild et al. 2003 published a case very similar to cases three and four, in which termination of pregnancy was opted for in view of the grave prognosis anticipated, due to the extent and rapid growth of a right leg lymphatic malformation, extending into the pelvis. An umbilical vein thrombosis was found on post-mortem examination. It is possible that in these cases thromboplastic substances released from the malformation may have played a part in the pathogenesis of a thrombosis, and/or thrombosis may have been a result of compression from the lymphatic malformation.

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is a congenital malformation syndrome characterized by disturbed growth (of bone or soft issue) in conjunction with a congenital vascular malformation (capillary, venous, or lymphatic; any arterio-venous components, if present, are very small and not significant) [Cohen, 2000; Oduber et al., 2008]. KTS can appear similar on ultrasound appearance to a combined vascular malformation and therefore should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Also in the differential diagnosis for combined vascular lesions seen on antenatal scans is primary lymphedema. Combined vascular malformations with lymphatic involvement can be distinguished from prenatal onset lymphedema by the macrocystic nature of the lesions. Lymphedema does not reveal cystic spaces within the abnormality. Use of color flow mapping can be helpful in determining the vessels involved.

Management of a pregnancy in which the diagnosis of a combined vascular/localized lymphatic malformation has been made, involves serial ultrasound scans. Monitoring for development of polyhydramnios is required, as it is a potential complicating factor that can induce preterm labor. In our experience these lesions can show a rapid rate of growth, which together with size and invasion of other structures, help to evaluate the prognosis for the fetus. Serial scans will enable the growth rate to be monitored and can help gauge the aggressive potential of the lesion. Fetal MRI may also be helpful as part of the assessment. The advice on the need for fetal karyotyping in lymphatic malformation cases varies. Mediastinal lymphatic malformations can be associated with Turner syndrome and Jung et al. 2000 therefore advocate fetal karyotyping in these cases. However, localized lymphatic malformations, apart from those ones involving the posterior aspect of the neck, are rarely associated with aneuploidy. This should be taken into consideration when deciding the need for an invasive fetal karyotyping procedure, following antenatal diagnosis of non-nuchal lymphatic malformations in the absence of other abnormalities.

Prenatal diagnosis enables the clinicians and parents to discuss management options for the pregnancy, and termination of pregnancy may be deemed appropriate in some cases in view of the extensive and progressive nature of these lesions. As Case 4 demonstrated, these lesions can result in intrauterine death, possibly due to an increased risk of thrombosis, and as in case two, even if the baby survives to term, infection can be fatal. Anomalies of this kind may be amenable to surgical treatment or sclerotherapy but the size, rate of growth and effect on surrounding tissues must all be considered when assessing the prognosis. Case five illustrates the severity of morbidity (pain, immobility, and infection) that can result from an extensive lesion.

The five cases described in this series, illustrate the serious nature of a prenatal diagnosis of localized lymphatic and combined vascular malformations and highlight the need for input from experienced clinicians when managing these pregnancies and counseling parents.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and families for kindly consenting to having their cases/photographs published. We are grateful to Dr. E. Pollina, King's College Hospital NHS Trust, London, for the post-mortem examination of case two. Thank you to Glen Brice, SW Thames Genetic Service, London, for his support.