Clinical outcomes in a cohort of patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

Funding information: NHLBI grants to the clinical and data coordinating centers; Grant numbers: HL072290, HL072033, HL072291, HL072196, HL072289, HL072191, HL072299, HL072305, HL072274, HL072028, HL072359, HL072072, HL072355, HL072346, HL072331, and HL072268; National Institutes of Health.

Abstract

Background

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a thrombotic disorder usually prompting treatment with non-heparin anticoagulants. The benefits and risks of such treatments have not been fully assessed.

Methods

We analyzed data for 442 patients having a positive heparin-platelet factor 4 antibody test and recent heparin exposure. The primary outcome was a composite endpoint (death, limb amputation/gangrene, or new thrombosis). Secondary outcomes included bleeding and the effect of anticoagulation.

Findings

Seventy-one patients (16%) had HIT with thrombosis (HIT-T); 284 (64%) had HIT without thrombosis (isolated HIT); 87 (20%) did not have HIT. An intermediate or high “4T” score was found in 85%, 58%, and 8% of the three respective groups. Non-heparin anticoagulation was begun in 80%, 56%, and 45%. The composite endpoint occurred in 48%, 36%, and 17% (P = .01) of which 61%, 38%, and 40% were receiving non-heparin anticoagulation. Compared with the no HIT group, the composite endpoint was significantly more likely in HIT-T [HR 2.48 (1.35-4.55), P = .003)] and marginally more likely in isolated HIT [HR 1.66 (0.96-2.85), P = .071]. Importantly, risk increased (HR 1.77, P = .02) after platelet transfusion. Major bleeding occurred in 48%, 36%, and 16% of the three groups (P = .005). Non-heparin anticoagulation was not associated with a reduction in composite endpoint events in either HIT group.

Interpretation

HIT patients have high risks of death, limb amputation/gangrene, thrombosis, and bleeding. Non-heparin anticoagulant treatment may not benefit all patients and should be considered only after careful assessment of the relative risks of thrombosis and bleeding in individual patients.

1 INTRODUCTION

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a major complication of heparin administration and causes thrombocytopenia without clinically symptomatic thrombosis (“isolated HIT”) or thrombosis with/without thrombocytopenia (HIT-T).1 In patients with heparin exposure and thrombocytopenia or thrombosis, heparin-PF4 antibody testing is often conducted and, if positive, generally leads to changes in patient care.

Before introduction of the non-heparin anticoagulants lepirudin and argatroban, the composite endpoint of death, limb amputation/gangrene, or new thrombosis occurred after diagnosis in 39%-52% of historical populations of HIT-T and isolated HIT patients;2-6 thrombosis occurred after diagnosis in 17%-59% of patients with isolated HIT.5, 7, 8 Compared with these unmatched historical controls, lepirudin and argatroban treatment reduced the composite endpoint rate.5-7 Nevertheless, up to 44% of HIT-T patients so treated still experienced composite endpoint events.5

Given widespread testing for HIT with the heparin-PF4 ELISA test and non-heparin anticoagulant use, we sought to determine whether the improved outcomes seen in prior HIT trials were observed in current practice in 19 major medical centers. A large cohort of consecutive patients with positive heparin-PF4 ELISA test was identified and frequency of HIT diagnosis, treatment, and risks of subsequent thrombotic and bleeding complications were assessed.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design

Retrospective chart review of consecutive subjects with positive heparin-PF4 ELISA test between January 21, 2008 and September 25, 2008 was conducted. Institutional Review Boards at 19 participating sites approved the study and waived consent.

Hospital records were reviewed for: patient demographics, duration/type of heparin exposure, platelet counts, thromboses, death, limb amputation/gangrene, bleeding, anticoagulant therapy, other causes of thrombocytopenia, type of heparin-PF4 ELISA test and its optical density (OD) value. Thrombotic events (except myocardial infarction, superficial thrombophlebitis) required radiographic confirmation. Day 0 was the day the heparin-PF4 ELISA test was sent. Inpatient data were obtained up to 28 days before Day 0 and until hospital discharge or Day 45, whichever was earlier.

Primary objective was to determine the risk of composite endpoint (death, limb amputation/gangrene, or new thrombosis) after Day 0. Secondary endpoints included death, limb amputation/gangrene, new thrombosis, and bleeding; platelet count recovery; relationship between non-heparin anticoagulant treatment or heparin-PF4 ELISA test OD value and clinical outcomes.

2.2 Definitions

Baseline platelet count: Highest platelet count before positive heparin-PF4 ELISA test was drawn.

Nadir platelet count: Lowest platelet count within ±5 days of Day 0 which is after the baseline count and not before first day of heparin exposure.

Thrombocytopenia: Nadir platelet count ≤50% of baseline.

HIT-T: Positive heparin-PF4 ELISA test and thrombotic event associated with heparin exposure within preceding 5 days, with/without thrombocytopenia.

Isolated HIT: Positive heparin-PF4 ELISA test and thrombocytopenia associated with heparin exposure in preceding 5 days, without new thrombotic event in preceeding 5 days.

No HIT: Positive heparin-PF4 ELISA test with heparin exposure in preceding 5 days, but not meeting criteria for HIT-T or isolated HIT.

New thrombotic event: Any arterial or venous thrombosis not present on Day 0.

Major bleeding event: Any 24 hour period in which ≥2 red blood cell (RBC) units were transfused, or radiographically confirmed intracranial hemorrhage.

Non-heparin anticoagulants: Lepirudin, argatroban, bivalirudin, desirudin, fondaparinux, but not warfarin or platelet inhibitory drugs (e.g., clopidogrel, aspirin).

“4T” score: Calculated for each subject using platelet counts, thrombosis diagnoses, timing of platelet count fall or thrombosis in relationship to heparin treatment dates, and whether medical record noted other reasons for thrombocytopenia.9

2.3 Statistical methods

Patients were eligible for analyses if they had heparin exposure as described above and sufficient data to determine whether they met criteria for HIT-T or isolated HIT. Patient characteristics were tested for differences among the three HIT diagnosis groups with one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Distributions were summarized as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. Time to event variables were compared using Kaplan-Meier plots and log-rank test statistics. Unadjusted proportional hazard models provided hazard ratios. Proportional hazards models with time-varying covariates were used to examine effect of platelet transfusion or use of alternative anticoagulant on time to clinical events. Missing data were not imputed.

2.4 Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patients

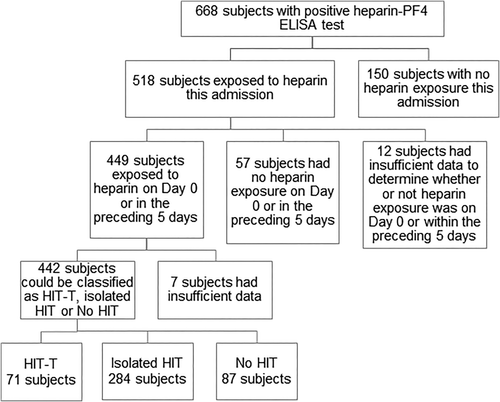

Of 668 consecutive patients with a positive heparin-PF4 ELISA test, 226 were excluded, primarily due to lack of recent heparin exposure (Figure 1). Of 442 evaluable patients, 71 (16%) had HIT-T [55 (77%) with thrombocytopenia]; 284 (64%) had isolated HIT; 87 (20%) had no HIT. An intermediate (4-5) or high probability (6-8) “4T” score9 was found in 85%, 58%, and 8% of the three respective groups (Supporting Information Figure S1).

Patient disposition.

The three groups did not differ in age, gender, admitting service, or type of heparin exposure (Table 1). Over 90% received unfractionated heparin and under 25% low molecular weight heparin; some received both. Mean length of hospital stay was greater in both HIT groups than in no HIT group (P < .001).

| HIT-T | Isolated HIT | No HIT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 71 | N = 284 | N = 87 | P-value* | ||

| Age, years; mean (SD) | 62 (16) | 59 (18) | 60 (19) | .41 | |

| Gender, male; n (%) | 32 (45) | 140 (49) | 47 (54) | .53 | |

| Heparin exposure this admission before D0; n (%) | UFH | 67 (94) | 263 (93) | 79 (91) | .72 |

| LMWH | 15 (21) | 48 (17) | 11 (13) | .37 | |

| Admitting Service; n (%) | CV/thoracic surgery | 18 (25) | 78 (28) | 18 (21) | .25 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 2 (3) | 9 (3) | 4 (5) | ||

| Other surgery | 15 (21) | 33 (12) | 8 (9) | ||

| Medicine | 36 (51) | 161 (57) | 56 (65) | ||

| Length of hospital stay, days; mean (SD) | 26 (14) | 35 (28) | 19 (19) | <.001 | |

| Baseline platelet count (×109/L); mean (SD) | 282 (168) | 270 (149) | 215 (172) | .01 | |

| Nadir platelet count (×109/L); mean (SD) | 90 (90) | 61 (33) | 163 (140) | <.001 | |

| Heparin-PF4 OD test results; n (%) | Assay ULN - 0.9 | 34 (48) | 163 (58) | 61 (70) | .02 |

| ≥ 1.0 | 37 (52) | 120 (42) | 26 (30) | ||

|

Heparin discontinued within 3 days after D0; n/total on heparin at Day 0 (%) |

45/49 (92) | 153/178 (86) | 43/51 (84) | .49 | |

|

Non-heparin anticoagulant used within 10 days of D0;n/total with data (%) |

57/71 (80) | 159/284 (56) | 39/87 (45) | <.001 | |

|

Duration of administration (days) of non-heparin anticoagulant; mean (SD) |

11 (9) | 11 (10) | 9 (8) | .58 | |

|

Discharged on non-heparin anticoagulant or warfarin; n/total discharged alive (%) |

37/51 (73) | 113/225 (50) | 41/78 (53) | .014 |

- Abbreviations: D0, Day 0, i.e. day positive PF-4 test was drawn; ULN, upper limit of normal; CV, cardiovascular; OD, optical density; SD, standard deviation; UFH, unfractionated heparin; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin. *P value compares all three groups.

3.2 Platelet counts

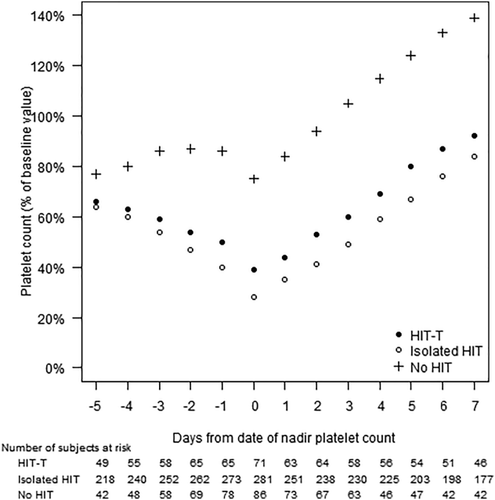

Nadir counts usually occurred on Day 0 [median day (Q1, Q3): 0 (–1, 2)]. Platelet time course was almost identical for the two HIT groups (Figure 2). Of patients with nadir platelet counts <100 × 109/L, recovery to ≥100 × 109/L occurred in 43/52 (83%) HIT-T and 193/249 (78%) isolated HIT patients after a median of 3 days.

Platelet count recovery. The mean platelet count (expressed as % of baseline value) is shown in relation to the day of the nadir platelet count. Solid circles, HIT-T (n = 71); open circles, isolated HIT (n = 284); crosses, no HIT (n = 87)

3.3 Treatment

On Day 0, 63% of patients still received heparin. Heparin was discontinued within the next 72 hours to an equal extent in all three groups (Table 1). However, use of non-heparin anticoagulation within the next 10 days differed significantly between the three groups (Table 1). Argatroban was most commonly used (60%), followed by bivalirudin (25%), fondaparinux (15%) and lepirudin (9%); some received more than one. Mean inpatient duration of non-heparin anticoagulant treatment was similar in all three groups (Table 1).

Among subjects discharged alive, more patients with HIT-T were discharged on non-heparin anticoagulant or warfarin compared to patients with isolated HIT or no HIT (Table 1). Warfarin was most commonly prescribed.

3.4 Clinical outcomes

3.4.1 Death, limb amputation/gangrene, new thrombosis

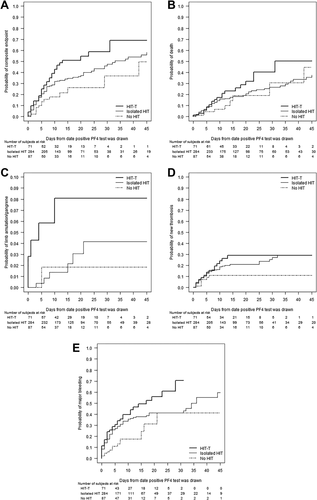

This composite endpoint occurred after Day 0 in 48%, 36%, and 17% of HIT-T, isolated HIT, and no HIT groups (Table 2); some had >1 composite endpoint event. Time to composite endpoint differed between groups (P = .01, Figure 3a) with most events occurring within the first 14 days for the two HIT groups. Compared with the no HIT group, hazard ratios for composite endpoint were 2.48 for HIT-T and 1.66 for isolated HIT (Table 2). These events occurred while on non-heparin anticoagulation in 61%, 38%, and 40% of the respective three groups. After taking the three groups into account, there was no relationship of composite endpoint (or any individual component) by hospital service.

Outcomes over time: (a) composite endpoint, P = .01; (b) death, P = .16; (c) limb amputation/gangrene, P = .08; (d) new thrombosis, P = .16; (e) major bleeding, P = .005. Heavy solid line, HIT-T (n = 71); light solid line, isolated HIT (n = 284); dashed line, no HIT (n = 87)

| HIT-T | Isolated HIT | No HIT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 71) | (n = 284) | (n = 87) | |

| Death, limb amputation/gangrene, or new thrombosis (P = .01) | |||

| Number (% of subjects) with this composite outcome | 34 (48) | 103 (36) | 15 (17) |

| Hazard ratio compared to no HIT group (95% CI) | 2.48 (1.35-4.55) | 1.66 (0.96-2.85) | – |

| P-value compared to no HIT group | 0.003 | 0.07 | – |

| Death (P = .16) | |||

| Number (% of subjects) who died | 20 (28) | 59 (21) | 9 (10) |

| Hazard ratio compared to no HIT group (95% CI) | 1.98 (0.90-4.36) | 1.31 (0.65-2.66) | – |

| P-value compared to no HIT group | 0.09 | 0.45 | – |

| Limb amputation/gangrene (P = .08) | |||

| Number (% of subjects) with limb amputation/gangrene | 5 (7) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Hazard ratio compared to no HIT group (95% CI) | 4.76 (0.55-40.87) | 1.35 (0.16-11.25) | – |

| P-value compared to no HIT group | 0.15 | 0.78 | – |

| New thrombosis (P = .16) | |||

| Number (% of subjects) with a new thrombosis | 16 (23) | 53 (19) | 7 (8) |

| Hazard ratio compared to no HIT group (95% CI) | 2.38 (0.98-5.79) | 1.91 (0.87-4.21) | – |

| P-value compared to no HIT group | 0.06 | 0.11 | – |

| Major bleeding event (P = .005) | |||

| Number (% of subjects) with a major bleeding event | 34 (48) | 102 (36) | 14 (16) |

| Hazard ratio compared to no HIT group (95% CI) | 2.80 (1.50-5.22) | 1.97 (1.12-3.45) | – |

| P-value compared to no HIT group | 0.001 | 0.02 | – |

Among patients with a composite endpoint event, platelet transfusions were infrequent (occurring in the preceding two days in 9% HIT-T, 16% isolated HIT and 0% no HIT groups) but after taking the three groups into account, transfusions were associated with increased risk of composite endpoint (HR = 1.77, 95% CI:1.09-2.89, P = .022).

3.4.2 Death

Although there was no statistically significant difference in time to death for the three groups (Figure 3b), hazard ratios were elevated for both HIT groups compared with no HIT group (Table 2). 21% of deaths occurred when patients were on non-heparin anticoagulation. After taking the three groups into account, platelet transfusion in the prior two days was a risk factor for death (HR = 2.81, 95% CI:1.54-5.12, P < .001).

3.4.3 Limb amputation/gangrene

Limb amputation/gangrene was infrequent (Table 2). Although there was no statistically significant difference between the three groups in time to this event (Figure 3c), the hazard ratio was markedly elevated for the HIT-T group versus no HIT group (Table 2). Most events (64%) occurred while on non-heparin anticoagulation and were not associated with platelet transfusion.

3.4.4 New thromboses

New thromboses occurred more frequently in HIT-T and isolated HIT groups compared to no HIT group (Table 2), although this did not reach statistical significance. Most events occurred within the first 14 days (Figure 3d). Most (64%) thromboses [74% venous (mostly DVT), 19% arterial (mostly stroke); 7% not defined] occurred while on anticoagulation. There was no association between new thrombosis and platelet transfusion.

3.4.5 Bleeding

Major bleeding occurred frequently in all three groups (Table 2) which differed in time to a major bleeding event (P = .005, Figure 3e). Among subjects with bleeding events, bleeding occurred while on non-heparin anticoagulation in 47%, 29%, and 29%, respectively. Intracranial bleeds occurred in about 1% of both HIT groups.

3.5 Effect of non-heparin anticoagulant on outcomes

Because a large number of events occurred while patients were receiving non-heparin anticoagulation, time-to-event analyses were conducted in HIT patients with a time-varying covariate indicating whether any non-heparin anticoagulant was used since Day 0. Of 316 evaluable subjects, 113 (36%) developed one of the composite outcome events. Marginally significant positive associations were seen between non-heparin anticoagulant use and time to occurrence of a composite endpoint event (HR 1.47, CI: 1.00-2.17, P = .052), and significant association with its new thrombosis component (HR 2.18, CI 1.20-3.95, P = .01). There was no statistically significant effect of non-heparin anticoagulation on death (HR 1.04, CI: 0.64-1.69, P = .87), limb amputation/gangrene (HR 3.29, CI: 0.58-18.59, P = .18), or major bleeding (HR 0.83, CI: 0.57-1.21, P = .33).

3.6 Heparin-PF4 ELISA test

The percentage of patients with OD values ≥1 varied significantly between the three groups (Table 1). However, there was no relationship between OD value and composite endpoint (P = .66).

3.7 Analysis of patients with intermediate or high 4T scores

Two hundred twenty-six patients (60 HIT-T; 166 isolated HIT) had intermediate or high 4T scores (Supporting Information Table S1; Figure S2). Compared to the isolated HIT subgroup, HIT-T patients were at significantly higher risk for composite outcome and major bleeding outcome. Time to death was marginally different between the two groups. Time to limb amputation/gangrene and time to new thrombosis were not significantly different. Significant positive associations were seen between non-heparin anticoagulant use and time to occurrence of a composite endpoint event (HR 2.02, CI: 1.18-3.45, P = .01) and with its new thrombosis component (HR 3.41, CI 1.47-7.86, P = .004). There was no statistically significant effect of non-heparin anticoagulation on death, limb amputation/gangrene, or major bleeding.

4 DISCUSSION

We sought to assess the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of patients with HIT in a large number of major medical centers in the United States. The majority of HIT patients had intermediate to high “4-T” scores suggesting an indication for treatment. However, despite frequent use of non-heparin anticoagulants, HIT-T and isolated HIT were associated with a high risk of death, limb amputation/gangrene, and/or new thrombosis. Furthermore, the risk of major bleeding in these patients was almost as high as the thrombotic risk measured by the composite outcome.

In this study, 80% of evaluable subjects met criteria for HIT/HIT-T, of which 80% had isolated HIT. This high prevalence of isolated HIT contrasts with prior treatment studies with lepirudin3, 4, 6 and argatroban5 where only 38% and 53% had isolated HIT.5, 6 This difference may be explained by current routine platelet count monitoring of patients on heparin10 and the focus of prior studies on treating more severely affected patients.3-6

The majority (58%) of all HIT patients were on medical services with fewer on cardiovascular/thoracic (26%) and orthopedic (3%) services, in contrast to prior studies where 66% of HIT patients were surgical (31% orthopedic) and 34% medical.7, 11, 12

Despite these differences, results of this study are comparable to prior studies in a number of ways: (1) Platelet count nadirs were 90 × 109/L and 61 × 109/L for HIT-T and isolated HIT groups;5 most recovered to >100 × 109/L by day 3.7 (2) Nearly three-quarters of thromboses were venous.7 (3) Almost all new thromboses occurred within 14 days.7 (4) Platelet transfusion was associated with increased risk of the composite endpoint.10 (5) Heparin-PF4 ELISA OD ≥1.0 predicted increased risk of having HIT8 but not increased risk of the composite endpoint.

In this study, HIT treatment was generally consistent with current guidelines.10 However, despite frequent use of non-heparin anticoagulants, risk of the composite endpoint for patients with HIT-T (48%) and isolated HIT (36%) was similar to a historical HIT population (57% and 39%) treated only with heparin discontinuation with or without warfarin.5 Individual endpoints of death (28% and 21%), limb amputation/gangrene (7% and 2%), and new thrombosis (23% and 19%) for respective HIT-T and isolated HIT groups were also very close to those in this historical HIT population [death (28% and 22%); limb amputation/gangrene (8.7% and 2%); new thrombosis (20% and 15%)].5

The benefit from non-heparin anticoagulant treatment for HIT in this study remains uncertain, as almost half of composite endpoint events and almost two-thirds of new thromboses occurred while on non-heparin anticoagulation. The purported benefits of non-heparin anticoagulation were based on non-randomized studies in which lepirudin-treated or argatroban-treated populations were compared with unmatched historical populations; indeed these studies are further confounded by the finding that 35-50% of argatroban-treated subjects and 19-35% of historical HIT subjects lacked a confirmatory HIT test.5 Argatroban treatment of isolated HIT yielded a composite endpoint of 26% versus 39% for historical controls (P = .014),5 but there was no statistically significant reduction in the composite endpoint for HIT-T patients. Lepirudin treatment of HIT patients (HIT-T and isolated HIT combined) reduced the composite endpoint to 30% versus 44% for historical controls (P = .0001).6 In both studies, treatment effects on the composite endpoint were reflected in significant reductions in new thrombosis rate without effect on death or limb amputation/gangrene.

Whether non-heparin anticoagulants had any impact on the composite endpoint or its individual components could not be assessed by our study in an unbiased way. Treatment was not randomized, and data were not available on factors influencing treatment decisions. Since not all centers routinely treated HIT patients with non-heparin anticoagulants (20% of HIT-T and 44% of isolated HIT patients did not receive any non-heparin anticoagulant between Days 0 and 10), we assessed the effect of non-heparin anticoagulant use on clinical outcomes. Time-to-event analyses showed an unexpected positive association between non-heparin anticoagulant use and both the composite endpoint and its new thrombosis component. Even when analysis was conducted in only HIT patients with intermediate or high 4T scores, this association remained significant. This association may simply reflect the bias to treat those patients felt to have a higher risk of thrombosis, but an alternative hypothesis is that asymptomatic thrombi are generated early in the HIT process and only become symptomatic days later, after non-heparin anticoagulation has been initiated.13

The high rate of the composite endpoint in our study is of concern because of the correspondingly very high rate of major bleeding. Major bleeding occurred in 48% of HIT-T and 36% of isolated HIT patients with well over half of events occurring when patients were not on non-heparin anticoagulation. Although the definition of major bleeding varied from prior studies, all included transfusion of ≥2 RBC units. Major bleeding occurred in 19.5% of lepirudin-treated patients versus 5.8% of historical controls (P = .0015).6 Argatroban treatment was associated with major bleeding in 11.1% of HIT-T and 3.1% of isolated HIT patients versus 8.2% and 2.2% for historical control patients.5 The much higher bleeding rate in the current study may reflect the medical complexity of the underlying disorders as well as the longer duration of follow-up. Patients with HIT-T or isolated HIT in this study had other major illness, inferred from their prolonged mean length of hospitalization (Table 1).

It is likely that some of the patients in this study would not have been diagnosed with HIT had SRA or IgG-specific heparin-PF4 ELISA tests or better clinical profiling tools been available and more widely used. While IgG-specific assays are now more widely used, a recent systematic review highlighted continued challenges in diagnostic assays, including heparin-PF4 ELISA tests.14 The SRA was used for confirmation at few enrolling institutions. While SRA data were not collected in this study, given the 4T scores in each group it would have been unlikely to influence therapy in the HIT-T group, but may have decreased the number of subjects who received non-heparin anticoagulants in the other two groups.

Nonetheless our patients reflect the practice of HIT diagnosis and treatment and are comparable to patients studied in prior treatment trials.5, 6 While the isolated HIT group might be influenced by some patients with low 4T clinical scores, similar proportions of patients in the prior treatment trials lacked even a confirmatory test for HIT. In this context, the high rate of the composite endpoint and high rate of bleeding call into question the modest benefits associated with non-heparin anticoagulation reported in prior studies. In our “real world” analysis, bleeding risks are high and apparent benefits of non-heparin anticoagulation difficult to estimate.

It has been reported that patients with heparin-PF4 ELISA OD values <1.0 correlate with a positive SRA only about 3% of the time15; about half of our two HIT groups had OD values <1.0. Although SRA was not used to confirm heparin-PF4 ELISA testing in our study, we observed no relationship of OD value with the composite endpoint.

The no HIT group deserves comment. Few had history of HIT and none had a thrombotic event or significant thrombocytopenia to warrant testing for HIT; over 90% had a low “4-T” score. Nonetheless they received non-heparin anticoagulation at almost the same rate as those with isolated HIT and were treated almost as long; thereby being unnecessarily exposed to anticoagulation risk and cost.

In addition to the caveats above, this study is limited by its retrospective nature and variable patient acuity. The strength of this study is that it reflects the state of HIT diagnosis and treatment in a large, representative patient population with a long follow-up period.

The diagnosis of HIT complicates patient care and is associated with increased risk of death, limb amputation/gangrene, or new thrombosis despite widespread use of non-heparin anticoagulation. Isolated HIT is associated with outcomes almost as poor as HIT-T. Although stopping heparin is associated with a rise in the platelet count, the degree of added benefit of non-heparin anticoagulant is unclear; the use of non-heparin anticoagulation needs to be re-considered given the high rates of new thrombosis and major bleeding seen in this patient population

In the future, better predictive clinical scoring schemes16 and improved assays may allow a more accurate diagnosis of HIT17 but new clinical studies documenting the risks and benefits of non-heparin anticoagulation will also be required in such more carefully defined HIT populations.

CONTRIBUTORS

DJK, BAK, THH, LU, SFA and TLO contributed to the original study design and data analysis. DJK, BAK, LU, JEK, RMK, NSK, BSS, JRH, PN, KRM, CL, RGS, JGM, EN, JBB, and TLO all contributed to data collection and analysis. DJK, BAK, THH, LU, SFA and TLO wrote the initial and all subsequent drafts of this manuscript, and all authors provided intellectual contributions to the manuscript, reviewed and revised its content, and approved the final version.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

We declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the many investigators and research coordinators in the Transfusion Medicine and Hemostasis Network who participated in this study. This work was funded by Grant Numbers HL072290, HL072033, HL072291, HL072196, HL072289, HL072191, HL072299, HL072305, HL072274, HL072028, HL072359, HL072072, HL072355, HL072346, HL072331, and HL072268 from the National Institutes of Health. The following investigators and staff participated in the study: University of Wisconsin, Madison: E. Williams (principal investigator), N. Turman; Froedert Memorial Lutheran Hospital, Milwaukee and St. Luke's Medical Center, Milwaukee: J. G. McFarland (principal investigator), D. Nischick; Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland: K.R. McCrae (principal investigator), Heesun Rogers, A. Smith, Y. Feng; Children's Hospital Boston, Boston: E.J. Neufeld (principal investigator), L. Lashley; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston: L. Uhl, E.R. Malynn; Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston: S. Sloan, R.M. Kaufman, L. Magazu, S. Slate; Weill College of Cornell University, New York: J. Bussel (principal investigator), N. Haq; Duke University, Durham: T.L. Ortel (principal investigator), S. Adam, L. Talbott, M. Gleim, N. Mace, P. Jordan; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore: P.M. Ness (principal investigator), R. Case, A. Fuller; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston: D. Kuter (principal investigator), M. Sanchez-Hernandez; Puget Sound Blood Center and University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle: S.J. Slichter (principal investigator), T. Gernsheimer, L. Fitzpatrick; Tulane University Hospital and Clinics, New Orleans: C. Leissinger (principal investigator), R. Kruse-Jarres, C. Fournet, A. Kinzie; University of Iowa, Iowa City: R.G. Strauss (principal investigator), J. Swift, University of Maryland, Baltimore: J.R. Hess (principal investigator), A.B. Zimrin, A. Anazado, T. Gonzales, S. Sarracco; Fairview–University Medical Center, Minneapolis: J. McCullough (principal investigator), T. Carr, S. Pulkrabek; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill: M.E. Brecher (principal investigator), A. Tsui, N. Key; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: B. Sachais (principal investigator), M. Kelty; University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh: D.J. Triulzi (principal investigator), P. D'Andrea; New England Research Institutes (Data Coordinating Center), Watertown: S.F. Assmann (principal investigator), E. Devlin, E. Gerstenberger, J. Ghannam, T. Hamze, K. Hayes; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda: T. Mondoro (project officer), S. Glynn