Factoring in the missing link

A physician or group of physicians considers presentation and evolution of a real clinical case, reacting to clinical information and data (boldface type). This is followed by a discussion/commentary

Conflict of interest: Nothing to report

A 51-year-old woman with a history of uterine fibroids presented with 2 weeks of persistent heavy vaginal bleeding. These symptoms developed in the setting of irregular menstrual cycles over the previous year. After 2 months without menstruation, she noted heavy, painless vaginal bleeding. She reported no abdominal pain, dysuria, nausea, vomiting, vaginal discharge, fever, chills, hot flashes, or night sweats.

Menorrhagia can be related to uterine fibroids, bleeding diatheses (most commonly von Willebrand disease), hypothyroidism, or advanced liver disease. Intermenstrual causes of vaginal bleeding include pregnancy, perimenopause, medications, intrauterine devices, infections (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease), or structural abnormalities, the most concerning of which is malignancy.

The presence of uterine fibroids could account for vaginal bleeding, but the persistence and excessive volume suggests an additional process. Endometrial cancer occurs in a significant number of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, often presenting as irregular painless vaginal bleeding. Rarely, uterine fibroids undergo sarcomatous degeneration, which may present as vaginal bleeding.

Past medical history included hypertension, nephrolithiasis, hyperlipidemia, and cholecystitis for which she underwent an uncomplicated cholecystectomy. Her Papanicolaou smears were normal and up-to-date. She had no history of sexually transmitted diseases. Her medications included metoprolol, iron supplementation, vitamin D, and multivitamins. She worked as a nurse in a methadone clinic. She was in a monogamous relationship with her husband and had three uncomplicated pregnancies. She never smoked tobacco or used illicit drugs and did not regularly consume alcohol.

The absence of prolonged bleeding during her prior cholecystectomy decreases the likelihood of an inherited bleeding disorder, which would be expected to manifest itself earlier. Her medications are not associated with an increased risk of bleeding. Occupational hazards for individuals within the health profession can include substance abuse and self-inflicted disease (e.g., surreptitious use of warfarin). Certain herbal supplements such as ginkgo can alter estrogen levels or clotting factors leading to irregular menstrual cycles.

On physical examination, the patient appeared well and in no distress. She was afebrile, with a pulse of 88 beats per minute, blood pressure 110/66 mmHg, and respiratory rate 18 breathes per minute. There was no conjunctival pallor. No rash, lymphadenopathy, or hepatosplenomegaly was detected. The cardiac, abdominal, and lung exams were normal. Soft tissue bruising and petechiae were noted on her upper extremities. There was moderate bilateral pitting edema of the lower extremities to the mid thighs. She had normal appearing external female genitalia. There was clotted blood visualized within the vaginal vault without evidence of active bleeding. No lesions or purulent discharge was observed in the vulva, vagina, or cervix. No cervical motion tenderness or pelvic mass was appreciated.

Bilateral lower extremity edema may result from increased intravascular hydrostatic pressure as seen in volume overload conditions or decreased intravascular oncotic pressure related to hypoalbuminemic states. The patient lacked evidence of volume overload. Hypoalbuminemia can result from malnutrition, defective protein synthesis, or excessive loss from protein-losing enteropathies or nephropathies. The patient did not have physical exam findings consistent with advanced cirrhosis. A protein-losing enteropathy is less likely given the absence of diarrhea. Protein-losing renal disease remains a possibility as it cannot be easily assessed by history or physical exam. Bilateral lower extremity edema can be caused by hypothyroidism and medications (e.g., amlodipine). Polycystic ovarian syndrome is unlikely in the absence of obesity, hirsutism, or acne. An adnexal mass was not detected, decreasing the possibility of an ovarian tumor, ectopic pregnancy, or cyst. The absence of pelvic pain, fever, and cervical motion tenderness would argue against pelvic inflammatory disease.

The urine human chorionic gonadotropin assay was negative. Electrolyte and aminotransferase levels were normal. The white blood cell count (WBC) was 9,600 per cubic millimeter, hematocrit 24.3%, mean corpuscular volume 86 femtoliters (normal range, 80–95), and the platelet count 441,000 per cubic millimeter. The prothrombin time (PT) was 34 sec (normal range, 12–14.4), international normalized ratio 3.5 (normal range, 0.8–1.2), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) 58 sec (normal range, 23.8–36.6). Albumin was 2.3 grams per deciliter, total protein 4.3 grams per deciliter (normal range, 6–8.3), and globulin 2 g per deciliter (normal range, 2.3–3.5). Urinalysis revealed 3+ protein, 1 WBC, and 28 red blood cells. Twenty-four hours urine protein and creatinine was 12,012 mg (normal value, <150 mg per day) and 926 mg (normal range, 8–170 mg per day), respectively. Fibrinogen level was 434 mg per deciliter (normal range, 200–400). A chest x-ray was clear without evidence of pleural effusions.

The constellation of edema, hypoalbuminemia, and marked proteinuria meets diagnostic criteria for nephrotic syndrome, which, paradoxical to this case, is usually associated with hypercoagulability secondary to loss of antithrombotic proteins such as protein C and S. Nephrotic syndrome can be a result of primary disorders, such as membranous nephropathy, or secondary causes, most commonly diabetes mellitus. While an abnormally elevated PT/INR or PTT can be explained by a disease process that affects both the extrinsic (factor VII) and intrinsic (factors VIII, IX, XI, and XII) pathways, respectively, a disturbance in the common pathway (factors II, V, and X) will concomitantly prolong the PT and PTT. The PT often becomes abnormal earlier than the PTT as an acquired common pathway factor deficiency evolves. Given the patient's age and unremarkable bleeding history, the coagulopathy would likely have to be acquired rather than be a late manifestation of a congenital predisposition. Acquired coagulopathies are the result of factor inhibitors or deficiencies. Inhibitors can be generated by conditions driven by or related to immune dysfunction. A fraction of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus will develop antiphospholipid antibodies, which can impact the measurement of the intrinsic pathway by prolonging PTT and typically manifest with thrombosis rather than bleeding. The most common acquired factor inhibitor targets factor VIII and may present as life-threatening bleeding. Autoantibodies against factor VIII can be a complication of solid tumors, usually adenocarcinomas, hematologic malignancies, most commonly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, the postpartum state, and medications. However, a factor VIII deficiency would only impact the intrinsic pathway and therefore prolong PTT without affecting PT/INR. An etiology is only discovered in about half the cases of factor inhibitors.

Serologic testing for antinuclear antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B antibody, hepatitis C antibody, cryoglobulins, and human immunodeficiency virus antibody were negative. Levels of rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody were within normal limits.

A mixing study should be performed to evaluate for the presence of an inhibitor. An inhibitor with slow kinetics, often seen in the case of factor VIII inhibitors, more effectively binds factor after incubation, demonstrating a normalized PTT initially and an uncorrected PTT after 1 or 2 hr.

The INR and PTT corrected immediately as well as at 1 and 2 hr incubations during the mixing study.

The negative mixing study essentially excludes the presence of an inhibitor and suggests a factor deficiency. Deficiency in factor levels of II, V, or X—components of the common pathway—can certainly explain a prolonged INR and PTT. Defective protein synthesis in cirrhosis leads to a deficiency in most clotting factors except for VIII, which is predominantly produced by the endothelium. Vitamin K deficiency or its interference by warfarin will selectively decrease factor II, VII, IX, and X activity levels, whereas factor V and VIII activity levels would be preserved. Disseminated intravascular coagulation, which is improbable given the preserved platelet count and fibrinogen level, will indiscriminately decrease activity of all coagulation factors (Table 1).

| Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 7 | 8 | 10 | |

| DIC | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Liver Disease | ↓ | ↓ | − | ↓ |

| Vitamin K Deficiency | − | ↓ | − | ↓ |

| The Patient | − | − | − | ↓ |

- Activity levels of these factors can be screened while evaluating a coagulation aberrancy that is suspected to be secondary to a factor deficiency. The factory activity levels in our patients were as follows: Factor II = 210%, Factor V = 177%, Factor VII = 137%, Factor X = 3%.

Factor activity levels were as follows: Factor II 210%, factor V 177%, factor VII 137%, factor VIII 97%, factor IX 89%, and factor X 3% (ref range for all factors tested, 50–150). Profilnine (Coagulation Factor IX complex) and factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activity (FEIBA anti-inhibitor coagulant complex) was given with temporary improvement in factor activity levels, which rose to 5% when measured a half hour after product administration, and reduction in vaginal bleeding.

The coagulopathy appears to be due to an acquired, isolated factor X deficiency. Light-chain (AL) amyloidosis is a condition that can manifest with nephrotic syndrome and factor X deficiency. Evaluation of select organs with not only a predilection for AL amyloid deposition but also suspected involvement in this patient should be strongly considered. In parallel, protein electrophoresis of the serum (SPEP) and 24-hr urine collection (UPEP), immunoglobulin levels, and serum free light chain (FLC) levels can be measured to evaluate for a plasma cell dyscrasia.

SPEP and UPEP with immunofixation demonstrated a faint M-spike and monoclonal gammopathy with free lambda paraprotein. Kappa FLCs were 5.5 mg per liter (normal range, 3.3–19.4), lambda FLC was 265 mg per liter (normal range, 5.7–26.3), and kappa to lambda FLC ratio was 0.02 (normal ratio, 0.26–1.65). IgG level was 304 mg/dl (normal range, 620–1,400), IgA 53 mg/dl (normal range, 80–350), and IgM 29 mg/dl (normal range, 45–250).

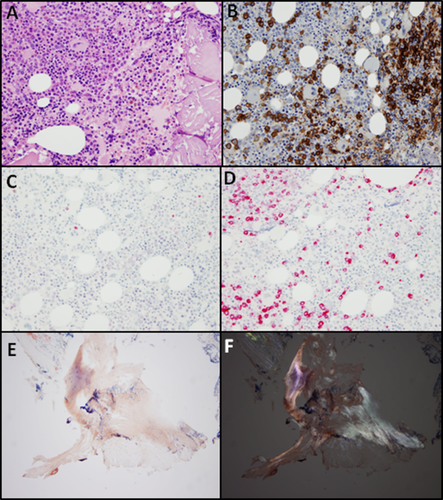

A transthoracic echocardiogram showed moderate concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle, restrictive filling, and normal ejection fraction. Cardiac MRI did not demonstrate specific findings attributable to cardiac amyloid infiltration. Whole-body 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan demonstrated increased fludeoxyglucose uptake in the heart and bone marrow. No discrete osseous lesions were present on imaging. Renal biopsy was not pursued given the high risk of bleeding due to the coagulopathy. Flow cytometric analysis of the bone marrow aspirate disclosed a clonal plasma cell population with immunoglobulin lambda light chain restriction. Histopathological, immunohistochemical, and in situ hybridization analysis of the bone marrow specimen confirmed an increased number of CD138-positive, lambda restricted plasma cells (Fig. 1A–D), consistent with involvement by a plasma cell neoplasm. Congo red staining of the bone marrow specimen revealed green birefringence under polarized light indicating the presence of amyloid fibrils (Fig. 1E,F). Fluorescence in situ hybridization uncovered a t(11;14) chromosomal translocation, which juxtaposes immunglobulin heavy chain and BCL-1, leading to the overexpression of cell cycle regulator Cyclin D1.

Bone marrow biopsy specimen. (A) low-power H&E, (B) CD138 immunohistochemistry, (C) Kappa light-chain in situ hybridization, (D) Lambda light-chain in situ hybridization, (E) Congo red stain, (F) Congo red stain visualized under polarized light. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The patient started combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD) for AL amyloidosis. FLC levels rose to 304 mg/l after 3 months of treatment indicating primary refractory disease; factor X levels remained less than 5% and NT-proBNP rose to 5,181 pg/ml. She was subsequently treated with melphalan, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, which yielded a partial response as lambda FLC levels dropped to 72 mg/l after 2 months of therapy. A splenectomy was performed in an attempt to improve factor X levels, however, it was complicated by a hepatic subcapsular hematoma despite hematological support. Before undergoing a planned autologous stem cell transplant, the patient died, 13 months after the diagnosis was established.

Discussion

Acquired, isolated deficiency of factor X is rare, however, when it does occur, AL amyloidosis is the most common cause 1. Less common etiologies include malignancy such as gastric adenocarcinoma, infections such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and medications such as sodium valproate. Factor X deficiency more commonly occurs in liver dysfunction, warfarin use, vitamin K deficiency, and DIC, but a concomitant reduction in activity levels of additional factors is usually observed (Table 1). Factor X is a vitamin K dependent protease that acts in the common pathway by cleaving, and thereby activating, prothrombin. It is the most common coagulation factor to be affected in AL amyloidosis; activity levels were found to be less than 50% of normal in 8.7% of cases 2. Factor X is thought to be sequestered by amyloid fibrils 3, shortening the plasma half-life and, inconsiderate to the depth of deficiency, it can showcase an unpredictable gradation of altered hemostasis. Still, symptomatic bleeding occurs in a substantial fraction of patients with factor X deficiency. While factor concentrates can be used as a temporizing measure, they seldom lead to sustainable improvements in factor X activity levels. As observed in this patient, the rapid binding of exogenous factors by amyloid is difficult to outcompete. Benefits must be weighed against risk when deciding to use FEIBA, which carries a risk for thrombosis. Support for using FEIBA in AL amyloidosis is limited to case reports 4. Splenectomy can improve factor X levels in a subset of patients, presumably by eliminating a source of intimate amyloid-vascular interaction; however, these are higher risk surgeries given the bleeding predisposition as was seen in this patient 5. Addressing the plasma cell dyscrasia will ultimately provide the best opportunity for a durable recovery in factor X levels.

AL amyloidosis, also known as primary systemic amyloidosis, is the most common form of amyloidosis, accounting for just over three quarters of cases 6. It occurs when a clonal plasma cell population elaborates an abnormally folded immunoglobulin light-chain with the potential to deposit in tissue throughout the body. Although AL amyloidosis is most often secondary to a plasma cell dyscrasia, it can less commonly be associated with other B cell lymphoproliferative diseases including non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia 7. When related to multiple myeloma, a lambda light chain isotype is usually secreted 8, whereas a kappa light-chain isotype is typically associated with Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Indiscriminant of the associated condition, advanced AL amyloidosis is rapidly fatal if left untreated.

The disease phenotype is heterogeneous and directly related to the tissue tropism of the particular misfolded light-chain amyloid fibril: cardiac involvement occurs in 75% of cases and can present with biventricular hypertrophic restrictive cardiomyopathy with a characteristic zebra pattern on MRI (biventricular subendocardial enhancement leading to a striped appearance) 9; kidneys are affected in 65% of cases and manifest as nephrotic syndrome with albuminuria; liver, peripheral nerves, gastrointestinal tract, soft tissue, and bone marrow can also be involved albeit less frequently. AL amyloidosis is often recognized late; 40% of patients are diagnosed a year after the onset of symptoms 10. It is therefore not surprising that 30% of patients present with irreversible organ damage at the time of diagnosis, portending a very poor outcome as these patients often succumb within a year. Early clinical suspicion coupled with appropriate diagnostics can alter the disease course by enabling effective treatment strategies to operate during an interval before irreparable harm has occurred.

Biomarkers are sensitive but not specific in AL amyloidosis. NT-proBNP is abnormal in cardiac AL amyloidosis and elevated levels portend a poor prognosis 11. The evaluation of serum FLCs is critical as it is more sensitive than protein electrophoresis; the latter can return an absent or faint M-spike owing to a minor clonal B-cell burden. Moreover, the difference between the involved FLC and uninvolved FLC, known as FLC-difference, carries independent prognostic value: patients with a lambda FLC difference greater than 18.2 mg/dl, as was the case for this patient, have an average overall survival of 10.9 months as opposed to 37.1 months for patients with a FLC difference less than 18.2 mg/dl 8. A tissue biopsy showing amyloid fibrils that display green birefringence when stained with Congo red will confirm the diagnosis. Fine needle aspiration of the abdominal fat pad is easily performed, low risk, and yields a diagnostic sensitivity of 81% 12. If clinical suspicion remains high despite a negative abdominal fat pad biopsy, the salivary gland, which provides 60% sensitivity in this setting 13, or an involved organ can be biopsied after careful assessment of risk. Since there are more than 30 types of amyloid deposits, molecular characterization of the amyloid fibril is necessary to rule out other amyloid subtypes that are paired with distinct interventions 14. The two approaches used are immunohistochemical testing with amyloid-specific antibodies 15 and mass spectrometry-based proteomic analyses 16.

The prognosis for AL amyloidosis is dependent in part on the degree of cardiac dysfunction. Infusion of patient-derived amyloid-forming light-chains led to heart failure in animal models by increasing apoptosis and oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes 17. Patients who do not respond to standard therapy can still survive for many years in the absence of cardiac involvement. However, patients with severe cardiac dysfunction can succumb in as short as a few weeks. It is therefore not surprising that the cardiac injury markers NT-BNP and troponin-T hold prognostic value. When combined with the increased FLC-difference, the elevated NT-BNP and troponin-T levels in this patient placed her in the Stage IV category based on a modified prognostication model, carrying an overall survival of 6.7 months 18.

The initial step in treating AL amyloidosis is to eradicate the abnormal plasma cell clone using chemotherapy. Although lenalidomide is an active agent in multiple myeloma, largely through selective protein degradation of IKZF1, it tends to be less tolerated by patients with AL amyloidosis. The protease inhibitor bortezomib in combination with dexamethasone comprise the backbone of therapy. Melphalan, an alkalating chemotherapy, is often added to these two drugs; the combination has proven to be less active in patients who harbor a gain in chromosome 1q21 19. Cyclophosphamide, a cytotoxic nitrogen mustard, is the other agent combined with bortezomib and dexamethasone. It is worth noting that translocation t(11;14) is associated with poor outcomes in patients treated with bortezomib-based regimens 20. Consistent with these findings, this patient was primary refractory to the initial therapy of CyBorD. Once a partial or complete response is achieved, consolidation with high-dose melphalan followed by an autologous stem cell rescue is typically pursued. If tolerated, this approach can lead to a hematological complete response and restoration of factor X levels. However, autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with AL amyloidosis and factor X deficiency is imbued with high risk as it can be associated with severe and sometimes fatal complications 2. Newer therapies directed at binding and stabilizing amyloid particles are in development and show promise as an adjuvant to treatment directed at the responsible plasma cell clone. Early recognition will be the key factor that links a patient to a desired outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following colleagues for their contribution to this case: Dr. Jeffrey Craig, Brigham and Women's Hospital Department of Pathology; Dr. Odise Cenaj, Brigham and Women's Hospital Department of Pathology; Dr. Paul Blanc, University of California, San Francisco Department of Medicine.