Massive pneumoperitoneum with abdominal pain and fever mimicking delayed perforation following endoscopic resection: A case report

Funding information: E-Da Hospital, Grant/Award Number: EDAHP108008

Abstract

Pneumoperitoneum has been reported as an intraprocedural or acute postprocedural adverse event resulting from advanced endoscopic intervention. Here, we report a case of a massive pneumoperitoneum-mimicking delayed perforation after colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection. A 60-year-old man received endoscopic submucosal dissection for a large colon polyp. Room air was inadvertently used in the first half of the procedure. After 12 hours, the patient developed fever, abdominal pain, and bilateral shoulder pain, and massive pneumoperitoneum was detected through plain film and computed tomography. After urgent diagnostic paracentesis, the patient's symptoms dramatically improved, and laparotomy was avoided. Massive pneumoperitoneum rarely occurs in patients receiving complex and long-standing endoscopic procedures, and it may manifest similarly to delayed perforation. Prompt diagnostic paracentesis is valuable when the diagnosis is uncertain.

1 INTRODUCTION

Advanced endoscopic techniques, such as endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), are typically required to completely remove large colon polyps. In particular, ESD is preferable for lesions with a risk of malignant transformation, because it allows for en-bloc resection, which is valuable for subsequent pathologic evaluations.1 However, ESD is also associated with long procedure times and high rates of perforation.2 Although immediate perforation may be treated with endoscopic closure, delayed perforation typically requires surgery.3 Hence, accurate diagnosis and management are required if symptoms or signs of delayed perforation are suspected after ESD. Here, we present a case of massive pneumoperitoneum-mimicking delayed perforation after ESD.

2 CASE REPORT

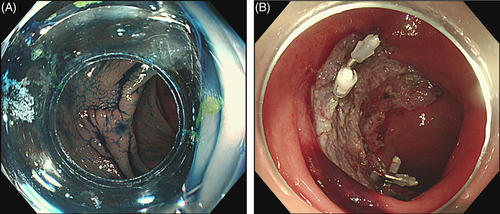

A 60-year-old man received ESD for a 35-mm laterally spreading tumor at the transverse colon (Figure 1A). The operation time was more than 4 hours. During the first half of the procedure, room air was inadvertently used, and pure carbon dioxide insufflation was used for the remaining procedure, after which several tiny muscle defects were closed with hemoclips. No visible defects or perforations appeared on the resection wound (Figure 1B). Two hours later, the patient's condition appeared favorable during a visit, and he was allowed to have a clear liquid diet.

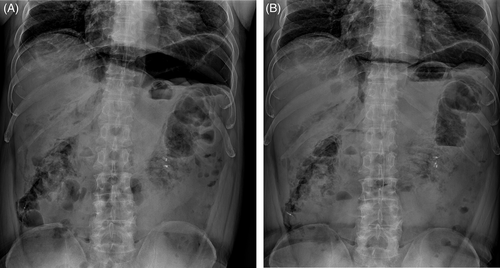

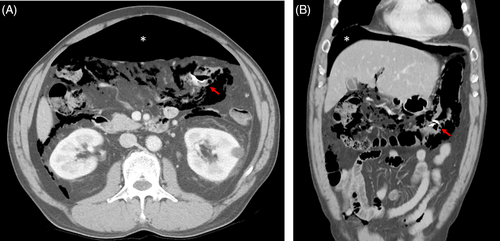

However, he began to experience fever, severe bloating, and bilateral shoulder pain the next morning (12 hours after ESD). His body temperature was 38.3°C, his heart rate was 90 beats per minute, his respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and his blood pressure 137/80 mmHg. Focused physical examination revealed a tympanic abdomen with mild bilateral upper quadrant tenderness and without rebounding tenderness or muscle guarding. Laboratory examination revealed white blood cell count of 12 800/mL (band 87%) and C-reactive protein levels of 89 mg/L. Abdominal X-rays (Figure 2A) and computed tomography revealed massive pneumoperitoneum (asterisk) without ascites or fat stranding around the resection site (red arrow, Figure 3).

As delayed perforation was suspected, urgent surgical consultation was sought. However, given the history of prolonged room air insufflation and the absence of peritoneal signs, iatrogenic pneumoperitoneum was considered more likely than colonic perforation. Hence, ultrasound-guided paracentesis was performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. We used a water-filled syringe with 18-gauge needle to punctuate a point 2 cm below the umbilicus. A large amount of air was then drained, and the patient's symptoms dramatically improved without the progression of physical examination findings. An immediate follow-up plain film after the procedure revealed decreased subphrenic air (Figure 2B). The patient was allowed to resume a clear liquid diet that day and was uneventfully discharged on the third day post-ESD with oral antibiotics. One week later, he was symptom-free during a follow-up visit, and his laboratory findings were completely normal. A final pathology of the polyp presented tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia.

3 DISCUSSION

Silent and mild pneumoperitoneum occurs in up to one-third of cases after ESD, and its incidence is independently associated with prolonged procedure time (>105 minutes). Possible causes include injection needle injury and transmural air leaks during submucosal dissection.4, 5 However, massive pneumoperitoneum has been rarely reported, particularly when room air is used during procedures.6-8 Previously reported symptomatic cases either involved tension pneumoperitoneum during procedures or pneumoperitoneum with abrupt onset after procedures. Hence, in these reports, the diagnosis could be ascertained with timely treatment. By contrast, our case had relative delayed presentation and thus the diagnosis was not straightforward.

Although mild asymptomatic pneumoperitoneum can be managed expectantly, paracentesis is indicated for tension pneumoperitoneum or severe abdominal pain and bloating caused by large volumes of air. In addition, improving symptoms after paracentesis may confirm a putative diagnosis. In our case, paracentesis was both diagnostic and therapeutic because the late onset raised concerns regarding delayed perforation, and pneumoperitoneum caused by room air requires active drainage for much slower in vivo absorption than that for carbon oxide.

Despite our case was more likely to have iatrogenic pneumoperitoneum based on the clinical presentation, physical signs, and the absence of ascites, early paracentesis remained crucial for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Based on the patient's improved symptoms, the patient was unlikely to have true colonic perforation. However, if the patient's symptoms or physical signs had aggravated after paracentesis, emergent laparotomy would have been performed without delay. Another interesting aspect was the gradual onset of his symptoms. We believed this was partly attributed to the post-anesthesia effect, and a concomitant post-ESD coagulation syndrome may have caused fever and aggravated symptoms.9 However, paracentesis does not have any beneficial effects for post-ESD coagulation syndrome, which involves transmural burns elicited by electrocauterization currents.

Although iatrogenic pneumoperitoneum generally has favorable prognosis with timely recognition, it may still cause substantial morbidity and may prolong hospitalization. Recently, a meta-analysis suggested that using room air may increase postoperative discomfort and adverse events more than when using carbon dioxide.10 Therefore, carbon oxide insufflation should be strongly considered during complex endoscopic procedures to minimize complications. In this case, though we anticipated barotrauma, regularly palpated the abdomen, and monitored blood pressure during the long procedure, no evidence of pneumoperitoneum appeared at the time. Thus, the lack of acute symptoms after procedures does not exclude the risk of adverse events, and close follow-up for up to 12 hours may be warranted.

In summary, massive pneumoperitoneum may rarely occur in patients receiving complex and long-standing endoscopic procedures, and this pneumoperitoneum manifests similar to delayed perforation. Prompt diagnostic paracentesis is valuable when diagnosis is uncertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.-H.Y. performed the therapeutic procedure, cared for the patient during hospitalization, and wrote the manuscript. J.-C.C. was also involved in manuscript writing. C.-W.L. contributed ideas and suggestions for manuscript organization. C.-C.H. was responsible for the follow-up visit and outpatient care of the patient. W.-L.W. helped refine the article and discussion.