Short-term outcomes of intracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer: A nationwide, multi-institutional cohort study in Japan (ICAN study)

The ICAN Collaborative Study Group members are co-authors of this study and are listed under the heading “Collaborators” at the end of the manuscript.

Abstract

Background

Several randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated the potential advantages of intracorporeal over extracorporeal anastomosis. However, the heterogeneity and small samples of these studies complicate drawing clear conclusions regarding such advantages. In this nationwide, multicenter, retrospective cohort study, we aimed to clarify the benefits of intracorporeal over extracorporeal anastomosis in patients undergoing laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer.

Methods

This study included 46 institutions. Patients with clinical stage 0–III colon adenocarcinoma who underwent laparoscopic colectomy between January 2020 and December 2021 were evaluated. The effect of intracorporeal anastomosis on short-term outcomes compared to extracorporeal anastomosis was assessed using propensity score matching.

Results

A total of 1245 patients (intracorporeal, n = 615; extracorporeal, n = 630) were included in the final analysis. The operative time was longer (228 vs. 207 min, p < 0.001), but blood loss was also lower (5.0 vs. 10.0 mL, p < 0.001) and the incidence of intraoperative vascular injury appeared lower (0.5% vs. 1.6%, p = 0.091) in the intracorporeal group than those in the extracorporeal group. The time to first passage of stool (2.9 vs. 3.5 days, p < 0.001) and length of hospital stay (9.3 vs. 10.2 days, p = 0.008) were shorter in the intracorporeal group.

Conclusions

Intracorporeal anastomosis showed advantages over extracorporeal anastomosis in terms of blood loss, intraoperative vascular injury (potentially), bowel recovery, and length of hospital stay, despite the longer operative time.

1 INTRODUCTION

Surgical procedures have advanced considerably over the last few decades, and among them, minimally invasive surgery, especially laparoscopic surgery, has been widely implemented for colon cancer. Several prospective, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown faster recovery of bowel function, less pain, and shorter hospital stay, along with oncological equivalence in laparoscopic colectomy compared with open colectomy.1-3 Since the introduction of minimally invasive surgery, the optimal anastomotic technique after colonic resection has been debated. Two well-established techniques are widely used. One is intracorporeal anastomosis (ICAN), in which the anastomosis is performed inside the abdominal cavity during minimally invasive surgery, and the other is extracorporeal anastomosis (ECAN), in which the anastomosis is performed outside the body. ECAN is the most common anastomosis performed by surgeons. However, in patients with thick abdominal walls or short mesenteries, extracting the bowel through a mini-laparotomy may be difficult, as it can lead to unexpected venous bleeding or mesenteric trauma.4-7 During ICAN, mesenteric dissection and anastomosis are performed within the abdominal cavity, which may avoid twisting and traction of the mesentery. Several RCTs and meta-analyses have shown the advantages of ICAN over ECAN, such as a shorter incision length,4, 7-11 lower incidence of paralytic ileus,5, 8, 9 and shorter length of hospital stay.10, 11 Others have found no significant differences between the two in the incision length,6, 12 paralytic ileus,7, 10-12 or length of hospital stay.5, 8, 12 The heterogeneity of retrospective studies and small samples of RCTs do not allow a clear conclusion regarding possible advantages of ICAN over ECAN.

This study aimed to clarify the benefits of ICAN compared to ECAN in patients undergoing laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer. The ICAN study was designed as a large, nationwide, multi-institutional cohort study. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed to minimize the inherent selection bias due to the retrospective design.

2 METHODS

2.1 Patients and study design

This multicenter, retrospective cohort study involved 46 Japanese institutions belonging to the Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery (JSLCS). This study included patients with clinical stage 0–III (Japanese Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and Anal Carcinoma13) colon adenocarcinoma who underwent laparoscopic colectomy between January 2020 and December 2021. All consecutive patients aged 20 years or older, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of less than 3, and with R0 resection were included. Exclusion criteria were emergency surgery, bowel obstruction, multiple primary cancers (disease-free period ≤5 years), previous colorectal resection, planned synchronous intra-abdominal surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, cT4 tumors, robotic surgery, stoma creation, and double-stapling technique-based anastomosis.

Most participating institutions are staffed by surgeons certified by the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery via the Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System.14-16 The surgical quality and performance of these institutions have been deemed favorable in several previous studies conducted by the JSLCS.14, 15, 17-19

This study was conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. An opt-out method was used to obtain consent for this study, which was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University (No. 2022-092-2). This study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry System in 2022 (UMIN000047994).

2.2 Covariates and outcome measures

For each patient, the records analyzed included the clinical characteristics, surgical data, postoperative outcomes, and pathological outcomes. Baseline patient characteristics comprised age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, comorbidities, previous abdominal surgery, tumor location, and tumor stage.13 N3 lymph node metastasis was defined as metastasis in the main lymph nodes.13 Preoperative management, intraoperative and postoperative variables were considered as the study outcomes, and included bowel preparation (e.g., mechanical preparation and/or oral antibiotics), surgical procedure, lymph node dissection, type of anastomosis (e.g., side-to-side iso-peristaltic anastomosis,20, 21 functional end-to-end anastomosis,22 delta-shaped anastomosis,23, 24 or end-to-end anastomosis), anastomosis fashion (e.g., stapled, stapled + hand-sewn, or hand-sewn), extraction site, intraperitoneal lavage, operative time, conversion to open surgery, intraoperative and postoperative complications (classified according to the Clavien–Dindo classification25), time to first passage of flatus/stool, length of hospital stay, and reoperation. D3 lymph node dissection was defined as dissection of the pericolic, intermediate, and main lymph nodes.13 Functional end-to-end anastomosis was defined as a side-to-side anti-peristaltic stapled anastomosis.22 Delta-shaped anastomosis was defined as an intracorporeal sutureless stapled end-to-end anastomosis.23, 24 The type of anastomosis was at the surgeon's discretion in each institution. No distinction was made regarding whether the complete division of the mesentery of the planned resected bowel, including the marginal artery, was performed intracorporeally or extracorporeally. If an incision longer than 8 cm was required to control intraoperative complications or tumor extension, the operation was considered an open conversion. Intraoperative complications were defined as those requiring additional repair, such as suturing of vessels, organ repair, or re-anastomosis. Postoperative complications were analyzed for ≥ grade II complications according to the Clavien–Dindo classification25 occurring by the first discharge date. Patients were treated and followed up after surgery according to the standardized protocols at each institution. In the ICAN group, the number of previous ICAN procedures performed at each institution at the time of surgery was evaluated for each patient.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The effect of ICAN on the short-term outcomes compared to ECAN was assessed using PSM. We used a logistic regression model to calculate the propensity scores. The model was based on the following potential confounding variables: age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists class, comorbidities (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and others), previous abdominal surgery, tumor location, clinical T category, clinical N category, and clinical stage. Matching was performed using the nearest-neighbor method with a caliper width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the propensity scores at a 1:1 ratio. Quantitative data are expressed as median and interquartile range or mean and standard deviation. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test or Student's t-test, and categorical variables were compared using Pearson's chi-squared test. All p-values were two-sided, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3 RESULTS

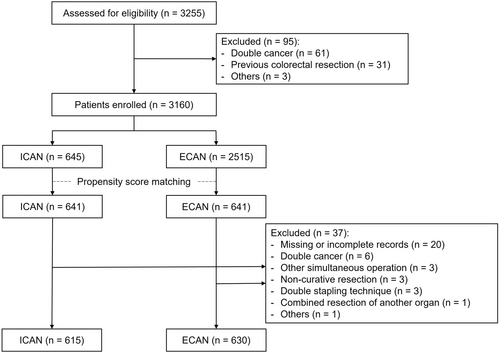

Between January 2020 and December 2021, 3255 patients were assessed for eligibility; 95 were excluded from the study. Therefore, the records of 3160 patients were analyzed (ICAN, n = 645; ECAN, n = 2515). After PSM, 641 matched patients were included in each of the ICAN and ECAN groups. Perioperative and pathological data were assessed, and after data cleaning, 37 patients were excluded. Finally, 1245 patients (ICAN, n = 615; ECAN, n = 630) were included in the analysis (Figure 1). A total of 113 patients (18.4%) were treated in institutions where fewer than 11 ICANs had been performed. The remaining 502 patients (81.6%) were treated in institutions where 11 or more ICANs had been performed. The patient characteristics before and after PSM are summarized in Table S1. Significant differences in age, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, other comorbidities, tumor location, and cT, cN, and cStage were observed between the two groups before PSM. After PSM, the two cohorts were well-matched in these characteristics. Table 1 shows the actual patient characteristics that were analyzed.

| ICAN (n = 615) | ECAN (n = 630) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 72 (65–78) | 72 (63–79) | >0.99 |

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 312:303 | 308:322 | 0.52 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 23.0 (20.6–25.7) | 23.0 (20.6–25.4) | 0.60 |

| ASA classification | 0.47 | ||

| 1 | 98 (15.9) | 116 (18.4) | |

| 2 | 459 (74.6) | 445 (70.6) | |

| 3 | 57 (9.3) | 68 (10.8) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Diabetes | 0.90 | ||

| Yes | 127 (20.7) | 132 (21.0) | |

| No | 488 (79.3) | 498 (79.0) | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.44 | ||

| Yes | 118 (19.2) | 132 (21.0) | |

| No | 497 (80.8) | 498 (79.0) | |

| Pulmonary diseases | 0.73 | ||

| Yes | 44 (7.2) | 42 (6.7) | |

| No | 571 (92.8) | 588 (93.3) | |

| Other comorbidities | 0.87 | ||

| Yes | 287 (46.7) | 291 (46.2) | |

| No | 328 (53.3) | 339 (53.8) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 0.73 | ||

| Yes | 189 (30.7) | 188 (29.8) | |

| No | 426 (69.3) | 442 (70.2) | |

| Tumor location | 0.98 | ||

| Cecum | 108 (17.6) | 107 (17.0) | |

| Ascending colon | 268 (43.6) | 293 (46.5) | |

| Right flexure | 16 (2.6) | 16 (2.5) | |

| Right transverse colon | 54 (8.8) | 53 (8.4) | |

| Middle transverse colon | 25 (4.1) | 27 (4.3) | |

| Left transverse colon | 29 (4.7) | 31 (4.9) | |

| Left flexure | 22 (3.6) | 20 (3.2) | |

| Descending colon | 61 (9.9) | 51 (8.1) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 32 (5.2) | 32 (5.1) | |

| Clinical T category | 0.83 | ||

| 0–1 | 173 (28.1) | 173 (27.5) | |

| 2 | 120 (19.5) | 131 (20.8) | |

| 3 | 243 (39.5) | 254 (40.3) | |

| 4a | 79 (12.8) | 72 (11.4) | |

| Clinical N category | 0.37 | ||

| 0 | 391 (63.6) | 408 (64.8) | |

| 1 | 169 (27.5) | 179 (28.4) | |

| 2 | 47 (7.6) | 33 (5.2) | |

| 3 | 8 (1.3) | 10 (1.6) | |

| Clinical stage | 0.97 | ||

| 0 | 6 (1.0) | 7 (1.1) | |

| 1 | 250 (40.7) | 258 (41.0) | |

| 2 | 135 (22.0) | 143 (22.7) | |

| 3 | 224 (36.4) | 222 (35.2) |

- Note: Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

- Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; ECAN, extracorporeal anastomosis; F, female; ICAN, intracorporeal anastomosis; IQR, interquartile range; M, male.

3.1 Preoperative management and intraoperative outcomes

The preoperative management and intraoperative outcomes are shown in Table 2. Bowel preparation was performed more frequently in the ICAN group than that in the ECAN group (96.3% vs. 76.2%, p < 0.001). Two patients converted from ICAN to ECAN owing to anastomotic problems. The underlying reasons were insufficient blood flow after anastomosis in one case and anastomotic failure in the other. Side-to-side iso-peristaltic (overlap) anastomosis was most commonly performed in the ICAN group (65.5%), whereas functional end-to-end anastomosis was most commonly performed in the ECAN group (90.0%). Anastomosis fashion was significantly different between the groups; staplers were used in 611 (99.3%) of the ICAN cases and 581 (92.2%) of the ECAN cases. The site of specimen extraction was also significantly different between the two groups, with the Pfannenstiel incision being used in only 15.1% of the patients in the ICAN group. The ICAN group had a significantly higher incidence of skin incisions <5 cm in length than the ECAN group. The operative time was significantly longer in the ICAN group (228 vs. 207 min, p < 0.001). Blood loss was significantly lower in the ICAN group (5.0 vs. 10.0 mL, p < 0.001). The frequency of intraoperative complications did not differ significantly between the ICAN and ECAN groups (1.1% vs. 2.4%, p = 0.13). The incidence of intraoperative vascular injury seemed lower in the ICAN group (0.5%) than that in the ECAN group (1.6%, p = 0.091). We conducted separate analyses for right- and left-sided colectomies. In the right-sided colectomy subgroup, the incidence of vascular injury seemed lower in the ICAN group (0.4%) than that in the ECAN group (1.7%, p = 0.065) (Table S2). Two cases of anastomotic problems were identified in the ECAN group, one of which required redo anastomosis owing to mesenteric twisting. One patient in the ECAN group underwent laparotomy for bladder injury repair.

| ICAN (n = 615) | ECAN (n = 630) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel preparation | 592 (96.3) | 480 (76.2) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical preparation only | 118 (19.2) | 256 (40.6) | |

| Oral antibiotic only | 35 (5.7) | 19 (3.0) | |

| Mechanical preparation + oral antibiotic | 439 (71.4) | 205 (32.6) | |

| Surgical procedure | 0.20 | ||

| Right-side colon | 488 (79.3) | 518 (82.2) | |

| Left-side colon | 127 (20.7) | 112 (17.8) | |

| Lymph node dissection | 0.42 | ||

| D1/D2 | 110 (17.9) | 124 (19.7) | |

| D3 | 505 (82.1) | 506 (80.3) | |

| Type of anastomosis | <0.001 | ||

| Side-to-side iso-peristaltic anastomosis | 403 (65.5) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Functional end-to-end anastomosis | 83 (13.5) | 567 (90.0) | |

| Delta-shaped anastomosis | 129 (21.0) | 3 (0.5) | |

| End-to-end anastomosis | 0 (0.0) | 54 (8.6) | |

| Others | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.6) | |

| Anastomosis technique | <0.001 | ||

| Stapled | 300 (48.8) | 571 (90.6) | |

| Stapled + hand-sewn | 311 (50.6) | 10 (1.6) | |

| Hand-sewn | 0 (0.0) | 36 (5.7) | |

| Others | 4 (0.7) | 13 (2.1) | |

| Extraction site | <0.001 | ||

| Umbilics | 514 (83.6) | 572 (90.8) | |

| Upper median | 3 (0.5) | 46 (7.3) | |

| Pfannenstiel | 93 (15.1) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Others | 5 (0.8) | 11 (1.7) | |

| Length of skin incision | <0.001 | ||

| <5 cm | 361 (58.7) | 158 (25.1) | |

| ≥5 cm | 128 (20.8) | 328 (52.1) | |

| Unknown | 126 (20.5) | 144 (22.9) | |

| Proximal margin (cm), mean (SD) | 12.4 (6.3) | 12.1 (6.4) | 0.54 |

| Distal margin (cm), mean (SD) | 11.7 (4.9) | 10.2 (4.0) | <0.001 |

| Intraperitoneal lavage | 437 (71.1) | 378 (60.0) | <0.001 |

| Operative time (min), median (IQR) | 228 (194–272) | 207 (169–257) | <0.001 |

| Blood loss (ml), median (IQR) | 5.0 (0.0–11.0) | 10.0 (3.0–35.0) | <0.001 |

| Intraoperative complicationa | 7 (1.1) | 15 (2.4) | 0.13 |

| Vascular injury | 3 (0.5) | 10 (1.6) | 0.091 |

| Organ injury | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) | 1.00 |

| Anastomosis trouble | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Open conversion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.32 |

- Note: Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

- Abbreviations: ECAN, extracorporeal anastomosis; ICAN, intracorporeal anastomosis; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

- a Two cases of ICAN were converted to ECAN owing to anastomotic problems (suspected insufficient blood flow in one case and anastomotic failure in the other) and were included in the ICAN group for analysis. Final case counts: ICAN = 617, ECAN = 628. Intraoperative complications were defined as events requiring additional interventions or repair.

3.2 Pathological outcomes

The pathological results are shown in Table 3. Assessment of the pathological features revealed no differences between the groups.

| ICAN (n = 615) | ECAN (n = 630) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter of tumor (mm), median (IQR) | 30 (20–47) | 31 (20–50) | 0.95 |

| Pathological T category | 0.22 | ||

| 0–1 | 179 (29.1) | 180 (28.6) | |

| 2 | 88 (14.3) | 100 (15.9) | |

| 3 | 290 (47.2) | 271 (43.0) | |

| 4 | 58 (9.4) | 79 (12.5) | |

| Pathological N category | 0.41 | ||

| 0 | 442 (71.9) | 438 (69.5) | |

| 1 | 117 (19.0) | 142 (22.5) | |

| 2 | 47 (7.6) | 40 (6.3) | |

| 3 | 9 (1.5) | 10 (1.6) | |

| Pathological stage | 0.62 | ||

| 0 | 26 (4.2) | 26 (4.1) | |

| I | 214 (34.8) | 223 (35.4) | |

| II | 197 (32.0) | 182 (28.9) | |

| III | 178 (28.9) | 199 (31.6) | |

| Harvested lymph nodes, median (IQR) | 24.0 (16.0–32.0) | 23.0 (15.0–33.0) | 0.47 |

- Note: Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

- Abbreviations: ECAN, extracorporeal anastomosis; ICAN, intracorporeal anastomosis; IQR, interquartile range.

3.3 Postoperative outcomes

The postoperative outcomes are shown in Table 4. No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of the postoperative complications (ICAN: 10.4% vs. ECAN: 8.7%, p = 0.31). The incidence rates of anastomotic bleeding, intraperitoneal infection, anastomotic stenosis, and anastomotic leakage, which are related to anastomosis, were also similar between the groups. No significant difference in the incidence of reoperation was observed between the two groups (Table S3). Although no significant difference in the time to first passage of flatus was observed, the time to first passage of stool (2.9 vs. 3.5 days, p < 0.001) and length of hospital stay (9.3 vs. 10.2 days, p = 0.008) were significantly shorter in the ICAN group.

| ICAN (n = 615) | ECAN (n = 630) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative complications | 64 (10.4) | 55 (8.7) | 0.31 |

| Anastomotic bleedinga | 0.89 | ||

| Grade II | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | |

| Grade IIIa | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Intraperitoneal bleedinga | >0.99 | ||

| Grade IIIb | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Grade IVa | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Intraperitoneal infectiona | 0.79 | ||

| Grade II | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Grade IIIa | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Grade IIIb | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Surgical wound infectiona | 0.26 | ||

| Grade II | 8 (1.3) | 4 (0.6) | |

| Paralytic ileusa | 0.86 | ||

| Grade II | 15 (2.4) | 14 (2.2) | |

| Grade IIIa | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Bowel obstructiona | >0.99 | ||

| Grade IIIb | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Anastomotic stenosisa | 0.74 | ||

| Grade IIIa | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Grade IIIb | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Anastomotic leakagea | 0.37 | ||

| Grade II | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Grade IIIb | 2 (0.3) | 5 (0.8) | |

| Othersa | 0.74 | ||

| Grade II | 17 (2.8) | 22 (3.5) | |

| Grade IIIa | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Grade IIIb | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Reoperation | 8 (1.3) | 10 (1.6) | 0.67 |

| Length of hospital stay (days), mean (SD) | 9.3 (4.8) | 10.2 (7.9) | 0.008 |

| Time to first passage of flatus (days), mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.3) | 0.096 |

| Time to first passage of stool (days), mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.6) | 3.5 (1.8) | <0.001 |

- Note: Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

- Abbreviations: ECAN, extracorporeal anastomosis; ICAN, intracorporeal anastomosis; SD, standard deviation.

- a Clavien–Dindo classification.

4 DISCUSSION

In the current study, ICAN in laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer was associated with a longer operative time but also with a reduced blood loss, a seemingly lower incidence of vascular injury, and a shorter skin incision than ECAN. The time to first passage of stool and length of hospital stay were also shorter. The strengths of this study include its large, nationwide, multi-institutional, cohort (>3000 patients with ICAN and ECAN), detailed clinicopathological parameters with few missing data points, and comparison of two PSM cohorts (>600 patients in each group). Another strength of this study is that the quality of surgery was assured by the participation of surgeons who have the Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System,14-16 which is evaluated by a video review of sigmoid colectomy or anterior resection.

In the current study, less blood loss was observed in the ICAN group. Although many reports have indicated that the intraoperative blood loss was comparable,4-6, 9, 10, 12, 20 Bollo et al.8 reported that the postoperative decrease in the hemoglobin level was lower and that gastrointestinal bleeding was less with ICAN than those with ECAN during laparoscopic right colectomy. The authors attributed this to the fact that the tension applied to the mesocolon at the time of specimen extraction and performance of ECAN could cause unnoticed bleeding from the mesocolon or Henle's trunk. Gastrointestinal bleeding could be attributed to differences in the anastomotic methods, including the type of stapler, but these did not differ in our study. In the current study, intraoperative vascular injury seemed less frequent in the ICAN group, particularly in the right-sided colectomy subgroup, than that in the ECAN group. As ICAN provides clear visualization of Henle's trunk and the mesentery, it may avoid the twisting and traction of the mesentery that can occur during ECAN, resulting in less bleeding.

Some researchers have reported that ICAN has a longer operative time than ECAN,5, 8, 9, 11, 20, 26 as in the present study, while others have claimed that it remains the same.4, 6, 7, 10, 12, 27 Anastomosis within the abdominal cavity is technically difficult and requires advanced technical skills in laparoscopic surgery. Ishizaki et al.28 demonstrated that the anastomotic time can be reduced with surgeon experience; 20 cases were required to achieve expertise in performing ICAN, using the cumulative sum method. In addition, ICAN can be performed in several ways, such as side-to-side iso-peristaltic anastomosis, functional end-to-end anastomosis, delta-shaped anastomosis, and end-to-end anastomosis, and operative time may differ among them. Differences between the anastomotic methods and the learning curve of each method should be considered when comparing operative time between groups. Therefore, we will incorporate these factors in subgroup analyses in future research.

In this study, a shorter skin incision was required in the ICAN group. During ICAN, the resected bowel is straightened and extracted through a smaller incision than that in ECAN. The smaller wound4, 7-11 may help to reduce postoperative pain and analgesic use in the ICAN group. Subgroup analyses of previous RCTs using an objective measure (visual analogue scale) revealed that some patients reported less pain,7, 8, 12 whereas others reported no change in the pain.6, 9 Vignali et al.9 considered that the same wound (periumbilical midline incision) was used for specimen retrieval in both groups; therefore, pain did not differ between groups. In a detailed analysis of analgesic use, Bollo et al.8 reported not only less pain but also less analgesic use with ICAN. However, Dohrn et al.6 found no difference in the pain or analgesic use between the two groups in a triple-blind, randomized trial with minimal risk of bias. Another advantage of ICAN is that specimen retrieval through the Pfannenstiel incision, while avoiding the umbilical incision, results in a lower incidence of incisional hernia.10, 11, 26 Incisional hernias are associated with long-term complications and reduced quality of life associated with reoperation. However, the percentage of Pfannenstiel incisions in the ICAN group in the present study was only 15.1% (93 cases), complicating the comparison of our results with those of previous studies. Lower,7, 10 equal,5, 8, 11, 12, 20 and higher rates of surgical site infection (SSI) have been reported in patients undergoing ICAN.26 The ICAN approach may carry a higher risk of SSI owing to potential leakage of intestinal contents into the peritoneal cavity. However, in our study, the shorter wound and the frequent use of combined mechanical bowel preparation and oral antibiotics in the ICAN group might have mitigated the difference in SSI rates. Bowel preparation is an important factor influencing SSI, and the use of both mechanical bowel preparation and oral antibiotics is recommended in guidelines.29

In the current study, the time to first passage of stool was shorter in the ICAN group than that in the ECAN group. Faster bowel recovery has been reported as one of the several advantages of ICAN. In particular, shorter time to first flatus,6, 10-12, 20, 27 passage of stool,4, 6, 8-12, 20 and oral intake10, 11, 20, 27 have been reported in patients undergoing ICAN. This may be because ICAN reduces unnecessary bowel mobilization and excessive traction on the mesentery during anastomosis.4, 20 Furthermore, ICAN may reduce the likelihood of direct bowel contact and exposure to outside air during anastomosis. Faster bowel recovery may lead to less paralytic ileus5, 8, 9; however, similar to previous reports,7, 10-12, 20 the difference was not statistically significant in the current study.

Postoperative intraperitoneal infection should be considered because of the potential for fecal contamination of the peritoneal cavity during ICAN. However, most previous reports have suggested that intraperitoneal infection is equivalent between ICAN and ECAN,7, 10, 11, 20 as was observed in the present study.

Similar to a previous meta-analysis,10, 11 the hospital stay was significantly shorter in the ICAN group. Although less pain and faster bowel recovery may lead to a shorter hospital stay, previous meta-analyses of RCTs5 and individual RCTs8, 12 have revealed that the hospital stay was comparable between the two groups. The results should be interpreted with caution, as the length of hospital stay is influenced by the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery program30 and bias cannot be excluded without blinded comparisons.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective cohort study, and PSM was used to minimize the inherent selection bias of the retrospective design. However, the substantial reduction in the number of cases in the ECAN group raises potential concerns regarding representativeness and statistical power. Moreover, given the large sample size (more than 600 cases in each group), certain factors, such as the 5-ml difference in blood loss between the groups, were statistically significant despite lacking clinical relevance. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, bowel preparation, the anastomotic method, the skin incision site, and the proportions of ICAN and ECAN cases varied across facilities. This study also did not include an analysis of the surgical experience of the surgeons or the size of the facilities. These factors might have influenced the results. Large-scale, prospective RCTs are warranted in the future. Third, robotic surgery, which is a minimally invasive procedure, was excluded. In Japan, robotic surgery for colon cancer has been covered by insurance since April 2022. Robotic surgery was one of the exclusion criteria because it included cases of novices who had just started performing robotic surgery. Future trials should include not only laparoscopic surgery, as in the MIRCAST study,31 but also robotic surgery. Fourth, the median body mass index in this study was 23. We are unsure whether the results of this study can be extrapolated to obese patients; however, ICAN may be useful in obese patients because they often have thicker abdominal walls and shorter mesenteries. Fifth, intraoperative complications include complications other than those related to the anastomosis. In such instances, the originally planned anastomotic method might have been altered, which might have influenced the outcome. Sixth, in this study, we analyzed right- and left-sided colectomies together. In the right-sided colectomy subgroup, the incidence of vascular injury appeared lower in the ICAN group than that in the ECAN group. However, the statistical trends for other parameters were similar across the total cohort and the individual subgroups for right- and left-sided colectomies. Seventh, in the present study, we compared short-term outcomes between groups, but the comparisons of multiple outcomes potentially introduced problems related to multiplicity. Long-term postoperative outcomes, with 3-year relapse-free survival as the primary endpoint, will be clarified in our future studies.

In conclusion, in this large, nationwide, multi-institutional cohort study with PSM, ICAN demonstrated advantages over ECAN in terms of blood loss, intraoperative vascular injury (potentially), bowel recovery, and length of hospital stay, despite the longer operative time. In the future, it is important to clarify long-term complications, including incisional hernia, recurrence-free survival, and peritoneal dissemination recurrence.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tomohiro Yamaguchi: Conceptualization; methodology; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Keitaro Tanaka: Conceptualization; data curation; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; visualization; writing – review and editing. Jun Watanabe: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Hiroki Hamamoto: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Atsushi Nishimura: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Fumihiko Fujita: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Hirokazu Suwa: Writing – review and editing. Masaaki Ito: Writing – review and editing. Kazushige Kawai: Writing – review and editing. Junichiro Hiro: Writing – review and editing. Seiichiro Yamamoto: Conceptualization; methodology; supervision; writing – review and editing. Sho Nambara: Writing – review and editing. Masato Ota: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; visualization; writing – review and editing. Yuri Ito: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; visualization; writing – review and editing. Junji Okuda: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Masafumi Inomata: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Masahiko Watanabe: Conceptualization; supervision; writing – review and editing. Takeshi Naitoh: Conceptualization; supervision; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following additional members of the Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery for their contributions to the conception and design of this study, and for useful discussion: T. Akiyoshi and T. Mukai (Cancer Institute Hospital of Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research); Y. Suwa (Yokohama City University Medical Center); K. Ikeda (National Cancer Center Hospital East); S. Natsume (Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Center Komagome Hospital); G. Inaguma (Fujita Health University); H. Ozawa and R. Nakanishi (Tochigi Cancer Center); K. Kobayashi and T. Hirokawa (Kariya Toyota General Hospital); A. Nomura, T. Okada, and S. Inamoto (Osaka Red Cross Hospital); Y. Todate and T. Miyakawa (Southern Tohoku General Hospital); R. Inada (Kochi Health Sciences Center); H. Takahashi and T. Suzuki (Nagoya City University Hospital); M. Miguchi (Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital); H. Kayano (Tokai University School of Medicine); S. Suzuki, A. Furutani, and N. Higashino (Hyogo Cancer Center); R. Makizumi (St. Marianna University Hospital); K. Okabayashi and K. Shigeta (Keio University Hospital); J. Kawamura and T. Wada (Kindai University Hospital); K. Hida and Y. Umemoto (Kyoto University Hospital); M. Numata and K. Kazama (Yokohama City University); K. Maeda and T. Fukuoka (Osaka Metropolitan University Hospital); M. Hotchi (Ehime Prefectural Central Hospital); H. Kobayashi (Teikyo University Mizonokuchi Hospital); H. Matsumoto (New Tokyo Hospital): S. Honma, S. Sano, S. Takahashi, and Y. Ohno (Sapporo-Kosei General Hospital); A. Kanazawa (Shimane Prefectural Central Hospital); E. Otsuji and T. Arita (Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine); H. Bando and S. Terai (Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital); M. Wakabayashi and M. Hosaka (Sagamihara Kyodo Hospital); T. Manabe and K. Okuyama (Saga University Hospital); T. Fukuda and S. Mukai (Chugoku Rosai Hospital); T. Nitta and M. Ishii (Shiroyama Hospital); T. Akagi (Oita university); Y. Kinugasa and M. Sasaki (Tokyo Medical and Dental University); T. Kobatake and R. Ochiai (Shikoku Cancer Center); S. Mori and K. Baba (Kagoshima University); M. Naito and R. Oshima (St. Marianna University Yokohama Seibu Hospital); K. Uehara and Y. Murata (Nagoya University); H. Nagano and S. Tomochika (Yamaguchi University); S. Ohnuma and T. Ono (Tohoku University); D. Yoshida (Beppu Medical Center); F. Motoi and S. Okazaki (Yamagata University Hospital); M. Takatsuki and T. Kinjo (Ryukyu University Hospital).

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study received funding from the Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery (JSLCS 21-01). The funding source had no role in the design, practice or analysis of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

T.Y. received honoraria for lectures from Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, and Intuitive, Inc.; J.W. received honoraria for lectures from Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, Eli Lilly, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and also received research funding from Medtronic, AMCO, TERUMO, and Stryker Japan outside of the submitted work; and F.F. received honoraria for lectures from Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, and Olympus, Inc. K.T., H.H., A.N., H.S., M.I., K.K., J.H., S.Y., S.N., M.O., Y.I., J.O., M.I., M.W., and T.N. have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose regarding this study. Co-authors include the following associate editors: Jun Watanabe, MD, PhD and Masafumi Inomata, MD, PhD.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: This study was conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The study protocol was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University (approval no. 2022-092-2).

Informed Consent: An opt-out method was used to obtain consent for this study.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: This study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry System in 2022 (UMIN000047994).

Animal Studies: N/A.