Bowel preparation and surgical site infections in laparoscopic and robot-assisted right-sided colon cancer surgery with intracorporeal anastomosis: A retrospective study

Abstract

Aim

Previous studies have examined bowel preparation as a measure to reduce surgical site infection (SSI) rates. This retrospective study aimed to identify the risk factors for SSI in right-sided colon cancer surgery using intracorporeal anastomosis (IA). We focused on perioperative factors, including the bowel preparation method, to clarify the impact of preoperative mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) and oral antibiotics (OA) on SSI incidence.

Methods

Patients (n = 150) with right-sided colon cancer who underwent elective laparoscopic or robot-assisted colectomy (2019 and 2023) were included. Potential risk factors for SSI were examined using univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

The overall incidence of SSI was 11 (7.3%) cases, with eight (5.4%) cases classified as incision site SSI and three (1.9%) as organ/space SSI. Univariate analysis showed that OA (p < 0.001) and MBP (p = 0.002) significantly reduced the SSI rate. Multivariate analysis identified OA as an independent risk factor (hazard ratio, 0.142; 95% confidence interval, 0.025–0.827; p = 0.025). Patients with SSI had longer postoperative hospital stays compared to those without SSI (median 9 vs. 8 days, p = 0.012). On postoperative day 1, the group receiving OA had significantly lower white blood cell count (9390 vs. 10 900/μL, p = 0.005) and C-reactive protein levels (3.81 vs. 7.83 mg/dL, p < 0.001) compared to those in the group not receiving OA.

Conclusion

Preoperative administration of OA in laparoscopic or robot-assisted right-sided colon cancer surgery with IA may help decrease the incidence of SSI.

1 INTRODUCTION

Surgical site infection (SSI) is a major complication of surgery associated with longer postoperative hospital stays and increased health care costs.1, 2 Various risk factors for SSI in colorectal cancer have been reported, including male sex, high body mass index (BMI), open surgery, prolonged surgical time, and bleeding.2, 3 In colorectal cancer surgery, care must be taken to prevent the occurrence of SSI due to contamination when the bowel is open. Therefore, many studies have been conducted on bowel preparation as a measure to reduce SSI risk. Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) was initially believed to decrease the bacterial load in the colon, thereby lowering the risk of SSI.4 Preoperative oral antibiotics (OA) have been reported in various studies to reduce incision site SSI5 by reducing the bacterial load in feces. Moreover, both randomized controlled trials6, 7 and clinical guidelines8-10 indicate that mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation (MOABP) can help prevent SSI and is recommended for colorectal cancer surgery. Morris et al., using American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program to analyze SSI in 8415 patients who underwent colorectal surgery, reported SSI rates of 14.9% with no preoperative preparation, 12.0% with MBP, and 6.5% with MOABP.11

Since the introduction of minimally invasive surgery, the optimal anastomotic technique for colonic resection remains controversial. Two well-established techniques are widely used. One is intracorporeal anastomosis (IA), in which the anastomosis is performed inside the abdominal cavity during minimally invasive surgery, and the other is extracorporeal anastomosis (EA), in which the anastomosis is performed outside the body. Although randomized controlled trials on long-term outcomes are not yet conclusive for right-sided colon cancer with IA, several randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have shown that, despite longer procedure12, 13 and anastomosis times14 compared to those of EA, IA can achieve favorable short-term outcomes such as faster recovery of bowel function,12 fewer cases of paralytic ileus,12, 13 shorter incision lengths,12, 13 less wound pain,13 and shorter postoperative hospital stays.13 In contrast, in IA, which requires opening the bowel within the abdominal cavity, increased spillage of feces into the abdominal cavity is expected to increase the risk of organ/space SSI.15, 16 There are conflicting reports on organ/space SSI, with some studies showing no difference17 and others indicating an increase in rates.15, 18 Reports on incisional SSI vary, with some suggesting a decrease,19 others no change,13 and some an increase20 in rates, making the relationship between IA and SSI controversial.

To identify the risk factors for SSI in colon cancer surgery, we aimed to examine perioperative factors as well as bowel preparation effects. However, as surgical procedures are heterogeneous when considering colon cancer as a whole, we limited our investigation to right-sided colon cancer surgery with IA.

2 METHODS

2.1 Patients

We retrospectively analyzed all patients with IA for primary right-sided colon cancer who underwent elective laparoscopic colectomy, including robot-assisted procedures, between July 2019 and November 2023 at the Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients who underwent emergency surgery, (b) patients who previously underwent surgery for colorectal cancer, (c) patients who underwent combined resection of another organ, and (d) patients who underwent surgery for diseases other than colon cancer. This study was conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. An opt-out method was used to obtain informed consent for this study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research of the Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (approval number 2018-GA-1030).

2.2 Study protocol

All patients were admitted to the hospital 2 days before their surgery, with food intake halted 1 day before the operation, and MBP was started. MBP was avoided in patients suspected of having preoperative bowel obstruction. In patients without MBP, IA was conducted after extending the preoperative hospitalization period and minimizing bowel contents through fasting. Since OA is not covered under the Japanese National Health Insurance system, its use is limited in Japan and was only implemented in our department beginning in April 2021. Our department performs an abdominal X-ray on all patients at admission. When significant stool retention is detected, we respond by initiating fasting and if necessary, add MBP starting 2 days before surgery. MBP was performed using magnesium citrate at 08:00 and sodium picosulfate at 11:00 (all times in Japan Standard Time) the day before surgery. OA was administered in two doses, 750 mg of metronidazole and 1000 mg of kanamycin, at 15:00 and 21:00 on the day before surgery. For MBP and OA, we applied the same approach as in our previous study and guidline.8, 21 The patient consumed an oral rehydration solution for up to 3 hours before anesthesia induction. Hair removal from the surgical field was performed the day before surgery. Skin was prepared using povidone-iodine. Each patient received 1 g of cefmetazole intravenously at least 30 min before skin incision, with subsequent doses administered every 3 h throughout the surgery until skin closure. Following the conclusion of surgery, an additional dose of intravenous prophylaxis was administered within 24 h. White blood cell (WBC) counts and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were routinely measured on the first postoperative day.

2.3 Surgical technique

In the IA, dissection of the mesocolon, transection of the bowel, and intracorporeal anastomosis were performed. The choice of anastomosis (side-to-side isoperistaltic anastomosis, functional end-to-end anastomosis, or delta-shaped anastomosis) was determined by the tumor location or surgeon's preference. The specimen was removed via a Pfannenstiel incision22 or an extended incision at the umbilical port site. For IA cases, our first choice when performing IA is generally a Pfannenstiel incision, especially when IA is planned preoperatively and the patient has a high BMI. However, this decision is ultimately left to the surgeon's discretion. A wound protector was used in all patients.

2.4 Determination of surgical site infection

SSI was defined based on the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.23 In summary, the criteria for incisional SSI included infections that occurred at the incision site within 30 days following the procedure, affecting the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and fascia, but not the organ/space. The criteria for organ/space SSI included infections occurring within 30 days of the procedure in any area of the body that was opened or manipulated during surgery, excluding the incision site. Additionally, at least one of the following conditions needed to be present: the presence of purulent fluid from a drain inserted into the organ/space; isolation of an organism from a culture of fluid from the organ/space; evidence of infection, such as an abscess or other abnormalities detected during direct examination, reoperation, or through histopathological or radiological assessment; or diagnosis of an organ/space SSI by the attending physician. Patients were monitored daily for signs of SSI by attending physicians and nurses until discharge, and follow-up examinations were conducted at the outpatient clinic for at least 30 days after surgery.

2.5 Candidate risk factors for SSI

We examined sex, age, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists-physical status (ASA-PS), tumor location, clinical stage (eighth edition of the TNM classification24), OA, MBP, robot-assisted surgery, type of operation, anastomosis, extraction site, operative time, and bleeding as the candidate risk factors for SSI. All SSI were assessed using the Clavien–Dindo Classification25 to determine their severity.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The JMP Pro 14.0 software package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Statistical analyses involved the Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. All factors with p < 0.05 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate analysis. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient characteristics

Initially, 152 patients who underwent right-sided colon cancer surgery for IA were included. Of these, a patient who underwent surgery for an ileal neuroendocrine tumor and another who underwent simultaneous hysterectomy were excluded. No patients were excluded based on exclusion criteria (a) or (b). Finally, we analyzed the data from 150 patients. Table 1 summarizes patient information. OA was administered to 102 (68.0%) patients, and MBP was performed in 134 (89.3%) patients. A Pfannenstiel incision was performed in 91 (60.7%) patients.

| Factors | n = 150 |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 69 (31–93) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 66 (44.0%) |

| Female | 84 (56.0%) |

| BMI, median (range), kg/m2 | 22.9 (16.9–44.7) |

| ASA-PS | |

| I | 46 (30.6%) |

| II | 98 (65.4%) |

| III | 6 (4.0%) |

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 38 (25.4%) |

| No | 112 (74.6%) |

| Diabetes | |

| Yes | 22 (14.7%) |

| No | 128 (85.3%) |

| Receipt steroid | |

| Yes | 1 (0.01%) |

| No | 149 (99.99%) |

| Tumor location | |

| Appendix | 3 (2.0%) |

| Cecum | 31 (20.7%) |

| Ascending colon | 62 (41.3%) |

| Transverse colon | 54 (36.0%) |

| cStage | |

| I | 63 (42.0%) |

| II | 36 (24.0%) |

| III | 39 (26.0%) |

| IV | 12 (8.0%) |

| Oral antibiotics | |

| Absence | 48 (32.0%) |

| Presence | 102 (68.0%) |

| Mechanical bowel preparation | |

| Absence | 16 (10.7%) |

| Presence | 134 (89.3%) |

| Operative procedure | |

| Laparoscopic | 131 (87.3%) |

| Robot-assisted | 19 (12.7%) |

| Type of operation | |

| Ileocecal resection | 46 (30.6%) |

| Right hemicolectomy | 86 (57.4%) |

| Transverse colectomy | 18 (12.0%) |

| Anastomosis | |

| Overlap | 124 (82.6%) |

| Delta-shaped anastamosis | 20 (13.4%) |

| FEEA | 6 (4.0%) |

| Extraction site | |

| Umbilicus | 59 (39.3%) |

| Pfannenstiel incision | 91 (60.7%) |

| Operation time, median (IQR), min | 236 (206–274) |

| Blood loss, median (IQR), mL | 10 (5–20) |

- Abbreviations: ASA-PS, American Society of Anesthesiologists-physical status; BMI, body mass index; FEEA, functional end to end anastomosis; IQR, interquartile range.

3.2 Incidence of SSI and postoperative course

The overall incidence and incision site and organ/space SSI rates in the present study are shown in Table 2. The overall incidence of SSI was 11 (7.3%) cases, with eight (5.4%) cases classified as incision site SSI and three (1.9%) as organ/space SSI. Among the three cases of organ/space SSI, two (1.3%) were complicated by anastomotic leakage. According to the Clavien–Dindo classification, all eight cases of incision site SSI were grade 1, whereas both cases of organ/space SSI were grade 2. One patient experienced a grade 3 complication requiring reoperation, with ileostomy creation performed on postoperative day 9 due to anastomotic leakage.

| Surgical site infection | Clavien–Dindo classification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Grade IV | |

| 11 (7.3%) | 8 (5.4%) | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Incision site | 8 (5.4%) | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Organ/space | 3 (1.9%) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Anastomotic leakage/Intra-abdominal abscess | 2 (1.3%)/1 (0.6%) | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/0 | 0/0 |

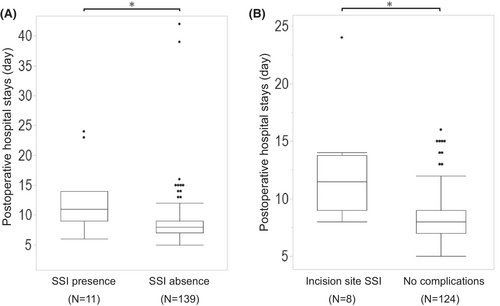

Postoperative hospital stays were longer in patients with SSI (median 9 days, range 6–24) than that in those without SSI (median 8 days, range 5–42) (p = 0.012) (Figure 1A). The wider range for patients without SSI reflects the inclusion of a case where postoperative bowel obstruction extended the hospital stay. Regarding the association between superficial incision site SSI and postoperative hospital stays, patients with incision site SSI had longer hospital stays (median 11.5 days, range 8–24), compared to those without any complications (median 8 days, range 5–16) (p = 0.002) (Figure 1B). The latter group excludes any patients with postoperative complications.

3.3 Risk factors for SSI

We compared the SSI-absent group and the SSI-present group on patient-related factors such as sex, age, BMI, ASA-PS, tumor location, tumor stage, OA, and MBP, as well as operative factors including robot-assisted procedures, type of operation, anastomosis, extraction site, operative duration, and intraoperative bleeding. In the univariate analysis, OA (p < 0.001) and MBP (p = 0.002) significantly reduced the incidence of SSI (Table 3). Multivariate analysis identified OA as an independent factor (hazard ratio, 0.142; 95% confidence interval, 0.025–0.827; p = 0.025) for reducing the incidence of SSI (Table 4).

| Surgical site infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | ||

| Factors | n = 139 (92.7%) | n = 11 (7.3%) | p value |

| Age, median (range), years | 69 (31–93) | 69 (46–84) | 0.986 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 64 (97.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 0.113 |

| Female | 75 (89.3%) | 9 (10.7%) | |

| BMI, median (range), kg/m2 | 23.0 (16.9–44.7) | 22.6 (18.7–36.2) | 0.399 |

| ASA-PS | |||

| I | 41 (89.1%) | 5 (10.9%) | 0.222 |

| II | 92 (93.9%) | 6 (6.1%) | |

| III | 6 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 35 (92.1%) | 3 (7.9%) | 1.000 |

| No | 104 (92.9%) | 8 (7.1%) | |

| Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 22 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.369 |

| No | 117 (91.4%) | 11 (8.6%) | |

| Receipt steroid | |||

| Yes | 1 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.000 |

| No | 138 (92.6%) | 11 (7.4%) | |

| Tumor location | |||

| Appendix | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0.387 |

| Cecum | 29 (93.5%) | 2 (6.5%) | |

| Ascending colon | 57 (91.9%) | 5 (8.1%) | |

| Transverse colon | 51 (94.4%) | 3 (5.6%) | |

| cStage | |||

| I | 60 (95.2%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0.756 |

| II | 32 (88.9%) | 4 (11.1%) | |

| III | 35 (89.7%) | 4 (10.3%) | |

| IV | 12 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Oral antibiotics | |||

| Absence | 39 (81.2%) | 9 (18.8%) | <0.001 |

| Presence | 100 (98.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Mechanical bowel preparation | |||

| Absence | 11 (68.8%) | 5 (31.2%) | 0.002 |

| Presence | 128 (95.5%) | 6 (4.5%) | |

| Robot-assisted or laparoscopic | |||

| Laparoscopic | 120 (91.6%) | 11 (8.4%) | 0.361 |

| Robot-assisted | 19 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Operative procedure | |||

| Ileocecal resection | 42 (91.3%) | 4 (8.7%) | 0.669 |

| Right hemicolectomy | 79 (91.8%) | 7 (8.2%) | |

| Transverse colectomy | 18 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Anastomosis | |||

| Overlap | 115 (92.7%) | 9 (7.3%) | 0.114 |

| Delta-shaped anastomosis | 19 (95.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | |

| FEEA | 5 (83.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Extraction site | |||

| Umbilicus | 55 (93.2%) | 4 (6.8%) | 1.000 |

| Pfannenstiel incision | 84 (92.3%) | 7 (7.7%) | |

| Operation time, median (IQR), min | 236 (208–274) | 222 (180–237) | 0.088 |

| Blood loss, median (IQR), ml | 10 (5–23) | 10 (6–18) | 0.554 |

- Abbreviation: ASA-PS, American Society of Anesthesiologists-physical status; BMI, body mass index; FEEA, functional end to end anastomosis; IQR, interquartile range; SSI, surgical site infection.

| Factors | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral antibiotics | 0.025 | ||

| Absence | 1 | - | |

| Presence | 0.142 | 0.025–0.827 | |

| Mechanical bowel preparation | 0.104 | ||

| Absence | 1 | - | |

| Presence | 0.279 | 0.060–1.299 |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SSI, surgical site infection.

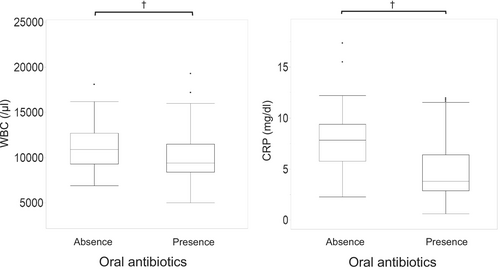

3.4 Oral antibiotics and postoperative inflammatory response

On postoperative day 1, the group receiving OA had significantly lower WBC count (median 9390 vs. 10 900/μL, p = 0.005) and CRP levels (median 3.81 vs. 7.83 mg/dL, p < 0.001) compared to the group not receiving OA (Figure 2).

4 DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrated that the administration of OA in laparoscopic or robot-assisted right-sided colon cancer surgery with IA was an independent factor for reducing SSI. Moreover, OA administration significantly reduced the postoperative inflammatory response the following day. The strengths of this study are that it uses data from consecutive laparoscopic or robot-assisted surgeries that focus exclusively on IA with the potential for fecal spillage, includes only right-sided colectomy because of the heterogeneity of surgical techniques when considering colectomy as a whole, and that perioperative management had not changed over the previous 4 years.

Nichols et al. reported that OA reduces SSI by decreasing the number of aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms in the colon.25, 26 Several reports have shown that OA is associated with a reduction in SSI after colorectal surgery.5-7, 9 These studies included cases of open surgery,5 rectal surgery,6 and were not limited to the right side or to IA in relation to anastomosis.10 Thus, the present study specifically focused on right-sided colon cancer surgery using laparoscopy or robot-assisted surgery for IA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate that the administration of OA reduces SSI in IA for laparoscopic and robot-assisted right-sided colon cancer surgery.

We have previously reported that OA use does not contribute to the reduction of SSI in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery.21 In this study, the incidence of SSI after right hemicolectomy was 9% in the non-OA group and 3% in the OA group, with a lower incidence in the OA group; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.152). We previously stated that this was because the subgroup analyses were exploratory and lacked the power to detect differences. Moreover, that study differed from the present study in that it was based on EA data and not on IA data.

MBP was originally thought to reduce the bacterial load in the colon, thereby reducing the risk of SSI.4 However, it has been reported to increase SSI and is not recommended when using preparation with MBP alone before colorectal surgery.27 In contrast, MOABP has been shown to reduce SSI during colorectal surgery.6, 8, 10 However, Koskenvuo et al. reported that MOABP did not reduce the incidence of SSI in colorectal surgery,28 and further reports indicated that it failed to reduce SSI in laparoscopic right-sided colon cancer surgery with EA.29 Thus, the effect of MOABP on SSI reduction after right-sided colon cancer surgery remains controversial. In our univariate analysis, MBP was associated with a reduction in SSI, suggesting that MBP may have beneficial effects. This may be because MBP reduces fecal spillage, which is a potential risk factor for SSI in patients with IA. In this study, all patients who received OA also underwent MBP. Consequently, we had no cases with OA alone, and our findings reflect the effects of MOABP. Our results suggest that the MOABP combination may contribute to SSI reduction, especially in right-sided colon cancer surgery. This suggests that combining MBP with OA, as in the MOABP strategy, may be an effective approach to reduce SSI in IA for right-sided colon cancer.

With IA for right-sided colon cancer, there is a concern about an increased risk of intra-abdominal infection due to the opening of the intestine into the abdominal cavity. Ishizuka et al.15 reported a significant increase in organ/space SSI not caused by anastomotic leakage in IA compared to EA for right-sided colon cancer. In the present study, there was one case of organ/space SSI that was not caused by anastomotic leakage, and no OA was administered. In the OA group, there were no cases of organ/space SSI caused by anastomotic leakage. However, there was no statistically significant difference between OA and organ/space SSI without anastomotic leakage (p = 0.313; data not shown). To validate whether OA reduces organ/space SSI in IA for right-sided colon cancer, further studies are necessary.

SSI significantly increased the length of postoperative hospital stays, resulting in increased medical costs.1, 2 It is widely assumed that the occurrence of SSI contributes to increased medical costs; moreover, Keenan et al. reported a 35.5% increase in medical costs associated with superficial SSI.1 In our study, patients with SSI had longer postoperative hospital stays compared to those in patients without SSI. In addition, patients with incision-site SSI had longer postoperative hospital stays compared to those in patients without postoperative complications. These results suggest that OA may contribute to early discharge by preventing SSI, which may reduce medical costs.

Surgical stress plays a key role in recovery outcomes. Markers of inflammation, including WBC count and tumor necrosis factor, interleukin, and CRP levels, are important in assessing surgical stress.30 Few studies have compared the postoperative inflammatory response after IA versus EA in colorectal cancer. Mari et al. reported a significantly lower inflammatory response such as interleukin-6, WBC, and CRP changes with IA, compared to those with EA, because IA minimizes tissue injury and inflammatory mobilization, which cannot be avoided with EA.31 However, there are conflicting reports of significantly higher WBC counts and CRP levels on postoperative day 1 in IA, compared to those in EA, for right-sided colon cancer.16, 17 This could be due to bacterial microcontamination caused by the release of bowel contents into the abdominal cavity. In the present study, patients who received preoperative OA for IA in right-sided colon cancer had significantly lower WBC counts and CRP levels on postoperative day 1 compared to those who did not receive OA. Among the 11 patients who developed SSI, the median day of SSI onset was 7 (range 4–10) days, and none developed SSI on postoperative day 1 (data not shown). These results suggest that OA may reduce the postoperative inflammatory response, regardless of the occurrence of SSI, by reducing bacterial microcontamination.

This study had several limitations. First, the retrospective single-center design, which relied on documentation from past medical records may have introduced a selection bias. Second, the selection of bowel preparation varied based on patient factors and the time period, which may have influenced the results. For patients with bowel obstruction prior to April 2021, preoperative preparation was not performed. IA was carried out only after verifying reduced bowel contents achieved through extended preoperative hospitalization and fasting. In our opinion, IA should not be administered to patients without preoperative preparation and present with a significant amount of bowel contents. Third, the small sample size of rare complications limits the clinical relevance of this study. Fourth, we did not consider other factors that may influence the development of SSI such as arterial hypoxemia, intraoperative hypotension, or hypothermia. Fifth, the surgeon's expertise and learning curve must be considered. Sixth, because we did not review each surgical video to assess the degree of contamination, the postoperative inflammatory response may have been influenced by the degree of fecal spillage into the abdominal cavity during surgery.

In conclusion, the use of preoperative OA in laparoscopic or robot-assisted right-sided colon cancer surgery with IA may help decrease the incidence of SSI. Future multicenter, large-scale prospective studies are required to confirm our results.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Naoya Ozawa: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Tomohiro Yamaguchi: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Takumi Kozu: Writing – review and editing. Tatsuki Noguchi: Writing – review and editing. Takashi Sakamoto: Writing – review and editing. Shimpei Matsui: Writing – review and editing. Toshiki Mukai: Writing – review and editing. Takashi Akiyoshi: Writing – review and editing. Yosuke Fukunaga: Writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

T.Y. received honoraria for lectures from Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, and Intuitive, Inc.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: This study conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research of the Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (approval number: 2018-GA-1030).

Informed Consent: N/A.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal Studies: N/A.