From the ground up: Creating and leading fellowship programs in emergency medicine

Special Issue: Proceedings from the SAEM 2021 Annual Meeting.

Supervising Editor: Dr. Daniel J. Egan

Abstract

Background

A methodical and evidence-based approach to the creation and implementation of fellowship programs is not well described in the graduate medical education literature. The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) convened an expert panel to promote standardization and excellence in fellowship training. The purpose of the expert panel was to develop a fellowship guide to give prospective fellowship directors the necessary skills to successfully implement and maintain a fellowship program.

Methods

Under direction of the SAEM Board of Directors, SAEM Education Committee, and SAEM Fellowship Approval Committee, a panel of content experts convened to develop a fellowship guide using an evidence-based approach and best practices content method. The resource guide was iteratively reviewed by all panel members.

Results

Utilizing Kern's six-step model as a conceptual framework, the fellowship guide summarizes the construction, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of a novel fellowship curriculum to meet the needs of trainees, educators, and sponsoring institutions. Other key areas addressed include Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and nonaccredited fellowships, programmatic assessment, finances, and recruitment.

Conclusions

The fellowship guide summarizes the conceptual framework, best practices, and strategies to create and implement a new fellowship program.

INTRODUCTION

The number of fellowships offered in emergency medicine (EM) has steadily increased over recent years.1 The Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) recommends that residents strongly consider pursuing a fellowship if they plan to enter an academic career.2 In this climate of increased need for fellowship positions, there is a parallel need to provide potential fellowship directors with clear guidance to create a successful fellowship program. This requires significant time and resources, particularly if the fellowship is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

For some subspecialties, the literature offers some guidance to faculty interested in creating a fellowship. A proposed curriculum and structure for a medical education fellowship has been published and evaluated.3, 4 A curricular framework has been described for global health fellowships, administrative fellowships and simulation fellowships, among others, along with an assessment model for global health fellowships.5-9 One institution combined the aspects common to several fellowships into a joint curriculum covering general topics such as scholarship and career development.10 While other specialties such as pediatrics have explored logistical concerns such as funding regarding their fellowship programs, the current EM literature offers little that describes the practical aspects of creating and leading a fellowship program.11

To address this gap in the literature, the authors sought to identify best practices for fellowship directors in creating and leading fellowship programs in EM. As described below, through the support of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM), the authors have developed a guide for prospective fellowship program directors to navigate the challenges of building a fellowship from the ground up. The authors aim to build on Kern's six-step model for curriculum development and describe key steps in systematically planning and implementing fellowship programs within departments or divisions of EM.12 The goal of this fellowship guide is to provide medical educators with a roadmap for establishing a subspecialty fellowship program that meets the needs of trainees, educators, and sponsoring institutions.

- Systemically plan and implement an individualized fellowship program curriculum using Kern's six-step model.12

- Secure buy-in from institutional and departmental leadership as well as financial support.

- Compare the merits of ACGME- and non–ACGME-accredited fellowships.

- Perform critical evaluation and assessment of both trainees and the fellowship program.

- Disseminate information on the fellowship program to recruit successful fellows.

METHODS

In May 2020, the SAEM Board of Directors charged the SAEM Education Committee (EC), in collaboration with the SAEM Fellowship Approval Committee (FAC), to create a resource guide for EM fellowship program development and implementation.

Within SAEM bylaws, the president-elect composes committees with SAEM members with expertise and/or interest in the subject matter pertinent to the specific committee. SAEM committee membership includes EM faculty, EM residents, and medical students interested in EM.13 From May 2020 through March 2021, the chairs of the EC and FAC identified and convened a panel of 10 content experts from within their respective committees to address the SAEM board charge. A description of the working group members’ experience and qualifications is provided in Table 1.

|

Clinical instructor Medical education fellow Junior assistant residency program director |

Associate professor Vice chair of education Medical education fellowship director |

|

Clinical instructor Medical education fellow Junior assistant residency program director |

Professor Chair of emergency medicine |

|

Assistant professor Director global health division Global health/international emergency medicine fellowship director |

Professor Executive vice chair for clinical operations and education Emergency medicine administrative and leadership fellowship director |

|

Professor Residency program director |

Assistant professor Associate residency program director Medical education fellowship director |

|

Associate professor Vice chair of education Medical education fellowship director |

Associate professor Associate residency program director Medical education fellowship director |

The work group convened in a virtual format as a whole and in subgroups for content development. To facilitate completion of the fellowship guide, subgroups were formed to investigate a key topic area; however, the entire group reviewed and informed the work of each subgroup prior to final approval of the resource guide. In developing the fellowship guide content, the group employed an evidence-based approach, prioritizing the highest quality data available. For topics in which minimal or no published evidence was identified, the content was informed by best practices identified by experts within the working group and outside experts interviewed by a working group member. The fellowship guide was iteratively revised by all working group members.

CONCEPT

ACGME- versus non–ACGME-accredited fellowships

The ACGME is the accreditation organization that sets the standards for U.S. residency and fellowship programs. The purpose of the ACGME is to provide program evaluation and review, ensuring that a sponsoring institution or program meets quality standards for graduates.14 Graduates of an ACGME-accredited fellowship are eligible to sit for their subspecialty board exam, which is particularly valuable for certain EM subspecialties. ACGME-accredited fellowships in EM include addiction medicine, clinical informatics, emergency medical services (EMS), medical toxicology, pediatric EM, sports medicine, and undersea and hyperbaric medicine.

Many EM fellowships and several subspecialties are not accredited by the ACGME. Non-ACGME programs are often overseen by the GME committee of the sponsoring institution. Foregoing ACGME accreditation allows for flexibility in compensation and benefits to fellows beyond their PGY level, which may be valuable for recruitment. However, because of the lack of oversight, fellowship content and curricula can vary more widely in non-ACGME fellowships.

If a fellowship is not accredited by the ACGME, there is an optional fellowship approval process through SAEM.15 SAEM recognizes non-ACGME fellowships by offering their approval of the fellowship personnel, goals, and content. This is a desirable option for non–ACGME-accredited fellowships to signify a high standard of training for fellows and support from the academic EM community. SAEM approval comes with many benefits including explicit milestones in curricular elements, faculty support recommendations, career development opportunities, and a certificate for fellows upon fellowship completion. Eligible fellowships include administration, disaster medicine, education scholarship, geriatric EM, telehealth, research, global health, and wilderness medicine.

Kern's model for curriculum development

General overview of Kern's model

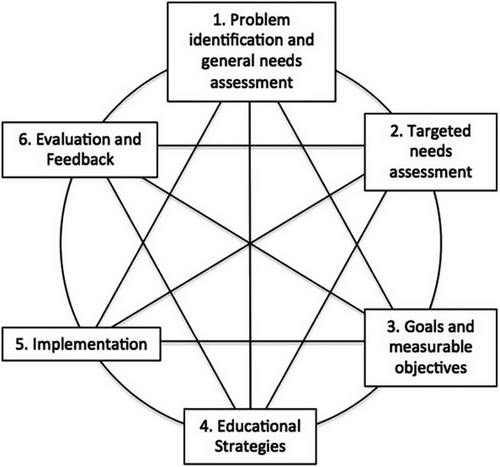

Accrediting bodies for undergraduate, graduate, and continuing medical education generally require a formal curriculum with explicitly stated goals, objectives, and evaluation strategies. David Kern, MD, MPH, developed a six-step systematic approach for medical educators that gives future fellowship directors the tools needed to clearly articulate educational goals and meet the needs of their learners, patients, and society.12 When developing or refining a fellowship curriculum, regardless of the field, Kern's six-step model can serve as a useful roadmap (Figure 1). Over the course of this fellowship guide, the authors discuss Kern's six-step model of curriculum development and its application in the construction, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of a novel fellowship curriculum.

Step 1: problem identification and general needs assessment

The essential aim of a curriculum in medical education is to prepare learners to address a problem that affects the health of a specific population. To accurately identify the problem, one should consider two guiding questions: Who does the problem affect? And what does the problem affect? To answer the first question, one should examine a variety of factors including the impact on patients, health care professionals, medical educators, and society.12 Second, how does the problem affect clinical outcomes, quality of life and health care, resource utilization, and societal function? For example, a toxicology fellowship may help improve the care of poisoned patients.

Once a problem has been adequately defined, one can begin the general needs assessment. The purpose of the general needs assessment is to determine the gaps between current and desired or ideal conditions.12 When starting a new fellowship, it is essential to investigate other local fellowships as well as similar fellowships at other institutions.

For example, when implementing a global health fellowship, begin with a systematic review of all information available about existing global health fellowships. The information can be obtained from medical literature, accreditation organizations, professional organizations, and consultations with experts in the field. After a thorough review of the current body of knowledge is completed, gather new information to gain a better understanding of what should be included in the ideal global health fellowship. Information gathering and data collection can be obtained by several methods such as the use of surveys, focus groups, and the Delphi method to obtain consensus on best practices for the fellowship's curriculum. In this example, the goal of the general needs assessment is to understand the differences between current practices and desired practices for global health fellowships.

Step 2: targeted needs assessment

A targeted needs assessment is the process of applying knowledge learned from the general needs assessment to obtain new information about the targeted learners and their environment.12 In the development of a new fellowship program, targeted learners will be the ideal future fellows. Information can be gathered from other local sources to include core faculty, fellowship directors, departmental experts, and national content experts.

After identifying who the ideal learner is, the next step is to identify the needs of the ideal learner. It is helpful to begin with the end in mind to understand the scope of knowledge a fellow is expected to attain after completion of fellowship. For example, what position should they be able to fill after completing fellowship? To identify the learner's needs, a fellowship director should explore their prior experiences and learning strategies, perceived and measured deficiencies, attitudes, and motivations.

In addition to understanding the ideal learner, it is critical to identify the stakeholders involved in the learning environment to ensure the fellowship's success. Additional stakeholders may include the chair, core faculty, departments, the sponsoring institution, and accrediting bodies (if applicable).12 Targeted needs assessment should also include financial support, faculty support, and additional resources from the department.

- What standards of representativeness, validity, and accuracy will be required?

- Will subjective or objective measures be used?

- Will quantitative or qualitative data be preferred?13

In summary, the targeted needs assessment focuses curricular efforts on the ideal learner and environment to further elicit the resources and stakeholders required to build a successful curriculum.

Step 3: goals and objectives

In the context of developing a fellowship, a goal is a broad, generalized overview of the direction a specific program or course plans to take. In contrast, learning objectives should be detailed aspects of goals that outline the process leading to desired outcome. The development of goals and objectives is vital in creating a fellowship curriculum as it guides curricular content, learning methods, and focuses the learner's expectations for evaluation. Learning objectives and goals can also facilitate distribution of important resources. Learning objectives should be evaluated routinely and refined based on Step 6, Evaluation and Feedback.

There are five basic elements to consider when developing learning objectives: time frame, the learner, the action verb, the degree, and assessment. Bloom's taxonomy provides a useful theoretical framework in creating meaningful learning objectives for higher level learning.17, 18 Objectives can be classified into three major categories including cognitive, affective, and psychomotor.12 When developing goals and learning objectives for a new fellowship program, it is important to utilize the SMART framework and create specific, measurable, attainable, result-oriented, and time-bound objectives that align with generalized goals of the program.19 An example illustrating the difference between goals and objectives is detailed below.

GOAL: By the end of this medical education fellowship the learner should become a valued member of a residency program leadership team.

- Develop and disseminate educational research as assessed by the number of presentations accepted at national conferences.

- Design innovative conference didactic sessions as assessed by postlecture resident feedback.

- Create longitudinal residency curriculum to address gaps in resident knowledge as assessed by exit interviews.

Step 4: Educational strategies

After clear goals and measurable learning objectives are developed, educational methods are selected that will most likely achieve the educational objectives and curricula goals. Prior to developing educational strategies for fellows, it is important to briefly review the needs of the adult learner.

The adult learner is self-directed and intrinsically motivated and uses life experiences to build an educational foundation.20 Knowles21 first described self-directed learning as a process where individuals take the initiative to identify their learning needs, formulate learning goals, identify resources, select and implement learning strategies, and monitor and evaluate their learning. As medical educators, it is important to find the right balance in guiding fellows to become self-directed learners. For example, a director of an administrative fellowship may decide to make only 70% of the curriculum mandatory, allowing their fellow to select relevant areas of interest for the remaining 30%.

- An explicit statement with learning objectives and methods.

- A schedule of the curriculum events and practical information.

- Curricular resources.

- Plan for assessment.

When determining educational methods, it is important to maintain congruence between objectives and the content. An engaging curriculum will utilize various educational methods that will be feasible in regard to time and resources. Examples of educational methods are provided in Table 2. To vary educational methods, implement educational technology including high-fidelity simulation, free open-access media, podcasts, and web-based learning modules. For example, an EMS fellow may benefit from medical control–simulated cases or a mass casualty drill.

| Simulation | Small-group discussions |

| Lectures | Advanced degree coursework |

| Leadership experience | Teaching |

| Flipped classroom | Curriculum development |

| Self-directed learning | Scholarship |

Step 5: implementation

During this step, the necessary actions are taken to make the fellowship a reality. This includes obtaining support, trialing the curriculum, initiating the program, and the dynamic process of constantly evaluating and refining the program.

Obtaining support

Obtaining institutional and departmental support for the fellowship program is a crucial step during implementation. The initial step includes acquiring support and buy-in from additional faculty members in the subspecialty and the administrative team in the department. The fellowship program team can consist of the fellowship director, assistant fellowship director, program coordinator, and additional core faculty members. Team size varies based on program size and resources. Often, faculty and program coordinators serve multiple roles within the residency and fellowship programs. Once a support team has been established within the department, the fellowship program can be presented to the GME office and hospital leadership. A new program may be required to seek approval from additional departments if the training program impacts multiple departments.

Identifying and procuring resources

One potential barrier to long-term success of a fellowship is sustainable funding. Local, institutional practices generally determine funding sources and mechanisms. Funding for ACGME-accredited fellowship programs typically falls to the sponsoring institution, whereas non-ACGME fellowship program funding is complex, derived from departments or divisions, grants, or even partnership with public entities or private industry. This presents both additional opportunities and challenges.

Strategies for funding of non–ACGME-accredited EM fellowships appear to be highly variable across institutions. No single, definitive best practice was identified; however, some common themes did emerge in our exploration. In general, to support long-term viability, fellowship programs should at least be budget neutral. Expenses to be considered include fellow(s) salary and benefits, fellowship director(s) stipend and/or reduction in clinical commitment, fellow malpractice coverage if practicing clinically as part of the program, institutional overhead expenses calculated and allocated per local practice, fellow CME/travel expenses, fellow membership in relevant national/regional organizations, and other resources to support fellow education and scholarly activity such as online access to journals, statistical analysis tools, etc.

In many EM fellowship programs funding to support the fellowship is primarily derived from revenue generated by fellows’ practice in clinical settings affiliated with the sponsoring institution. In a common model, fellows are paid a trainee salary based on local PGY norms for a predetermined clinical commitment. The difference between a faculty salary and a postgraduate trainee salary for that clinical commitment served to support the cost incurred for the fellows’ training. In many programs, fellows are given the opportunity to practice clinically beyond the base commitment to increase their overall salary. The additional clinical time appeared most often to be compensated at rates similar to junior faculty, although some models compensated fellows at a lower rate than faculty.

Alternative sources of funding were uncovered in our exploration, but they were rare. In a few cases, programs and/or fellows were able to secure scholarships to partially support salary or other fellowship-related expenses. In general, these appeared to be one-time opportunities or of limited duration. Philanthropy represents another potential alternative source of revenue. One EM fellowship program reported securing an endowment sufficient enough to support a portion of fellowship-related expenses in perpetuity. If the fellowship can provide a paid service or partner with a business or nongovernmental organization, it may be possible to generate funds to offset costs associated with the fellowship. This method is rare and can be complicated. It may require additional oversight, institutional buy-in, and approval.

Pursuit of additional degrees (e.g., master's, PhD) as part of a fellowship program adds further complexity to the funding model for fellowship programs. Funding for this portion of training appears to vary to an even greater degree among programs. Several EM fellowships report partnering with local institutional programs to arrange for a reduced tuition. Fellows may be required to work additional clinical shifts to offset the cost of an advanced degree. During investigation, rare cases of waived tuition were found due to established institutional policies or as a result of collaboration between the department and the program supporting the degree program.

Identifying and addressing barriers to implementation

What are the barriers to implementing the fellowship? Potential barriers to consider are buy-in from leadership, personnel including administrative personnel, buy-down for faculty time spent on education, space for fellowship activities including both clinical and educational spaces, equipment, potential impact on other training programs, and funding.

One step in the implementation phase that may identify additional barriers is trialing the curriculum via a pilot program. For example, for a medical education fellowship, the curriculum may be trialed via a medical education elective for residents. This provides an opportunity to elicit feedback. Once the curriculum and infrastructure for the fellowship are in place, the program is ready for the first fellow.

Step 6: evaluation and feedback

Evaluation and feedback should be occurring regularly as part of the interconnected model; however, at this stage, a critical question in the development and implementation of a fellowship curriculum can be answered: Were the desired goals and objectives met?12 Feedback should be collected from the learners, core faculty, and other stakeholders about both the individual's and the curriculum's performance. Various methods of collecting feedback exist, including surveys, interviews, clinical metrics, and coaching meetings. This information should be synthesized to modify and continuously improve the fellowship curriculum.

Program evaluation is the assessment of the performance of the individual and curriculum. Assessments can be both formative, allowing for ongoing feedback for learners and curriculum, and summative, allowing for a final grade of the performance of the learner and curriculum.22 The evaluation process includes the identification of users, resources, and ethical concerns.12 After the identification process, measurement methods can be designed to collect data. The analyzed data should be reported to important stakeholders involved in the fellowship process. This will allow for continued support and allotment of resources to support the fellowship program.

One evaluation framework often utilized in medical education is the Kirkpatrick Model. This model utilizes a tiered approach to further understand the learner's reactions, assessment of learning outcomes, extent of behavior change, and impact of the fellowship program.23 An additional method to provide guidance for the academic growth of fellows is the utilization of established committees to review the fellow's projects and scholarly productivity. Examples of these committees include scholarly oversite committees, medical education research committees, and core education committees.

Dissemination, branding, and recruitment

Disseminating a fellowship program refers to the process of either promoting the curriculum as a whole or promoting portions of the curriculum such as the needs assessment or evaluation results to new groups of learners.12 Dissemination has many benefits including preventing others from repeating the same work as well as providing recognition and academic advancement for the curriculum development.12 Dissemination of the curriculum can positively impact the health of a population and stimulate change on the local or national level.12 Lastly, it allows for the collaboration of medical educators and refinement of outside curricula. Dissemination of scholarly projects from the curriculum development process can be shared at the local or national level through lectures, abstracts, and publications.

To distinguish the fellowship program from other programs, consider the deliberate branding of the program. This includes the creation of an identity, image, and experience of the fellowship program. The brand of the fellowship program communicates the strengths, culture, and priorities of the program to both internal and prospective applicants and stakeholders. To define the program's brand, reflect on unifying mission statements, positive attributes, and unique features. For example, clearly demonstrating the department's commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion will serve prospective applicants. These elements can then be incorporated into promotional materials and the program's online presence.24

Multiple recruitment methods exist to promote fellowship information and interact with potential candidates. Aside from creating an information page on the departmental website, the fellowship listing may be posted on national organizational websites such as SAEM Fellowship Directory and the EMRA Match site.25, 26 In addition, departmental social media accounts including Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook can be utilized to post information about the new program. Residency and fellowship fairs are an additional method to promote the program and engage with potential applicants.27

Ensuring success

After creating, implementing, and recruiting a new fellow to the program, it is essential to take the appropriate steps to ensure their success within the program. This includes organizing a seamless transition, creating a sense of community, and developing avenues for mentorship. Incoming fellows should be oriented to the program's structure, administration team, didactic composition, clinical sites and flow, medical record software, and leadership team. Complete the orientation by adding incoming fellows to the appropriate meetings, committees, and listservs. An essential step in this process is to review important meeting times and didactic schedules ahead of schedule requests to guarantee their availability for participation.

The next step is to begin building the incoming fellows’ new community. It can be difficult for fellows to transition to a new program. For a smooth transition, build a tiered community for the fellow. Create open lines of communication with the fellowship program leadership team through texting groups or email chains. Work with other fellowship program directors to facilitate communication and community building between fellows from different programs. If there is a limited number of fellows, consider expanding this community to include new hires and past fellows. In addition, involve incoming fellows early on in medical student and residency didactics.

Lastly, develop a mentorship scheme with the incoming fellow. Review the goals of the incoming fellow and introduce them to junior and senior faculty with similar interests or career aspirations. Prior fellows are also a great resource to discuss pearls and pitfalls from their experience. Taking the time to transition the incoming fellow to their program will ensure their success during fellowship and set them up to achieve their personal, professional, and scholarly goals.

CONCLUSION

Though time-intensive, creating a new emergency medicine fellowship program can be an exciting professional endeavor. Drawing on existing literature and expert opinions, this guide uses Kern's six-step model for curriculum development as a preferred framework and recommends several current strategies and best practices for aspiring fellowship directors as they navigate program development. This guide summarizes a common educational framework and describes solutions to several administrative and logistical challenges facing fellowship programs across all specialties. While many emergency medicine fellowships are not accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the authors recommend adhering to many of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education fellowship program accreditation requirements to create a consistent learning and work environment across the sponsoring institution. Nascent fellowship directors can position their programs for success and longevity by securing buy-in from hospital and department leadership, engaging key stakeholders, establishing a sustainable funding model, and designing a robust curriculum with regular trainee assessments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript. Allison M. Beaulieu, Kimberly Bambach, and Andrew M. King provided supervision for the entirety of the concept paper.