Using community-based participatory research methods to inform care for patients experiencing homelessness: An opportunity for resident education on health care disparities

Supervising editor: Alden Landry, MD, MPH.

Abstract

People experiencing homelessness (PEH) suffer higher burdens of chronic illnesses, have higher rates of emergency medicine (ED) use and hospitalization, and ultimately are at increased risk for premature death compared to housed counterparts. Structural racism contributes to a disproportionate burden of homelessness among people of color. PEH experience not only significant medical concerns but also complex social needs that need to be addressed concurrently for effective healing, issues that have been magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic. As health disparities and structural racism intersect among PEH, it is critically important to develop PEH-centered interventions to improve care and health outcomes as part of an effort to dismantle racism. One opportunity to address these disparities in care for PEH is through training ED physicians on methods for identifying and intervening on the unique needs of vulnerable patient groups. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has outlined health quality pathways in the clinical learning environment to address health disparities. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is particularly well suited for this scenario as it allows experiential learning for trainees to work with and understand a diverse group of stakeholders, to deepen their knowledge of local health disparities, and to lead research and measure outcomes of interventions to tackle health disparities. In this paper, we highlight the utility of CBPR in fostering experiential learning for EM residents on tackling health disparities and the importance of community collaboration in trainee-led interventions for comprehensive ED care.

People experiencing homelessness (PEH) have complex social, as well as medical, needs and both must be addressed for effective healing.1-3 These social needs include safe housing, food security, and reliable methods of contact for follow-up, issues only amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic.4, 5 One opportunity to undertake disparities in care for PEH is through training ED physicians. Here we present a trainee-led collaboration with hospital and community-based stakeholders to design and implement targeted interventions for PEH. We highlight the utility of community-based participatory research (CBPR) in fostering experiential learning for emergency medicine (EM) residents on health disparities and the importance of community collaboration.

BACKGROUND

PEH suffer higher burdens of chronic illnesses, higher rates of ED use and hospitalization, and ultimately increased mortality as compared to housed counterparts.1, 2, 6 While the prevalence of homelessness among ED patients has been cited between 7%–18%, it is widely accepted to be underestimated due to a lack of systematic screening and stigma.7, 8 The COVID-19 pandemic continues to represent an unprecedented public health challenge, in which PEH are particularly vulnerable due to challenges of social distancing, lack of shelter, dependence on external services, increased medical comorbidities, and transience.5, 9, 10 The ED serves as a cornerstone of access for PEH and is a key site for implementing health disparity interventions.

Furthermore, health disparities and structural racism intersect among PEH, rendering PEH-centered interventions a critical part of addressing racism in medicine. While 17 per 10,000 people in the United States experienced homelessness overall last year, the numbers are considerably larger for Black Americans (55 per 10,000) and Latinxs (22 per 10,000).11 Racial bias in the criminal justice system and disproportionate incarceration among Black men contribute to homelessness through destabilized finances and decreased eligibility for social welfare programs, housing, and employment.12-15 Housing discrimination such as redlining has resulted in limited generational wealth and home ownership.16, 17 Additionally, discrimination within the homelessness response system has resulted in less favorable housing outcomes among people of color.18, 19 The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified these effects of structural racism, through disproportionate job loss and adverse economic consequences.19, 20

In our urban, medium-sized city of New Haven, Connecticut, the COVID-19 pandemic rapidly changed the landscape of resources available to PEH. Using CBPR principles, our homelessness taskforce (described below) identified key challenges for PEH during the pandemic. Congregate settings such as homeless shelters were forced to close and divert to hotel rooms.21 Drop-in centers, food and clothing banks, and many other services that PEH rely on had newly limited hours and capacities.22 Meanwhile, communication between the city and ED providers regarding these changes lacked sustained infrastructure to support information exchange. This led to unsafe hospital discharge plans, with countless examples of physician referrals to community resources rendered inaccessible because of the pandemic. Furthermore, there was a lack of communication regarding the role of COVID testing as a prerequisite to accessing available PEH community resources. Without this task force, systematically identifying and addressing the aforementioned barriers would likely have been delayed or have never occurred.

USING CBPR TO DEVELOP PANDEMIC RESPONSE PROGRAMS

CBPR and health disparity research

CBPR is a methodology that collaborates with populations of research interest and centers their voices in project conception, design, and implementation.23 It is a powerful research tool for addressing health disparities as it elevates and incorporates the perspectives of historically marginalized populations into the research process.24 CBPR has been described as a method for trainees to learn and apply principles of community collaboration and to develop understanding of the perspectives of those who will be impacted by their research.23 However, we are not aware of any literature describing how CBPR research can be used with EM residents to learn about health disparities and provide experiential learning to develop community partnerships and interventions.25-27

Planning and CBPR group formation

The authors of this paper constitute the leadership of a CBPR task force focused on improving care of ED patients experiencing homelessness.4 Our team has been meeting quarterly for 5 years and is composed of ED and hospital providers, social workers, care coordinators, street medicine and community health clinic providers, local advocates, and people with lived experience of homelessness.4

Identifying priorities during COVID-19

Using our connections to key stakeholders including city officials, social workers, community health workers, and nongovernment organization representatives, we identified barriers to resources through an iterative process with routine meetings. Problems identified included limited access to COVID testing due to technological and transportation barriers as well as the closure of an underutilized city-run respite center for COVID-positive PEH. Based on these findings, we aimed to improve access to community respite resources for PEH presenting to the ED.

Implementation

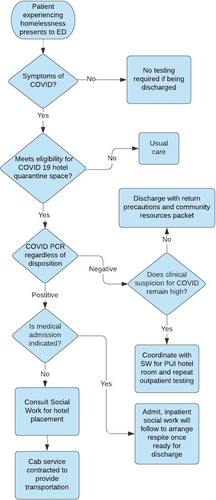

During the second wave, the city partnered with local stakeholders to place COVID-positive homeless patients in hotel rooms for their quarantine, with a street medicine team providing medical monitoring.28 Our group's work led to the development and implementation of a clinical pathway to refer symptomatic PEH presenting to the ED to quarantine hotel rooms, which would otherwise not have existed.

Using departmental patient data, local case positivity rates, and policy information from community leaders, we drafted a protocol based on the priorities of key stakeholders and obtained buy-in from our ED department's administration section. The protocol was distributed to ED attendings, residents, mid-level providers, and social workers. The pathway involved homeless patients with symptoms receiving rapid COVID testing, social work consultation, and referral and transport to a quarantining hotel room (Figure 1).

The process of implementation added another dimension to the CBPR experiential learning opportunity for EM trainees. In addition to gaining an in depth understanding of the needs of PEH, community organizations, and local governmental processes, the residents also had the opportunity to bridge the gap between the community and the clinical setting.

Outcomes and evaluation

The initial informal response to the protocol was well received by faculty, staff, and social work. Our plan for formal evaluation of the protocol's implementation entails semistructured interviews with interdisciplinary representation from care teams that have activated the pathway, employing the consolidated framework for implementation research, a validated tool for assessing feasibility and acceptability.29

Our outcome measures of interest include number of PEH receiving COVID tests in the ED, number of pathway activations, number of social work consults, length of stay, and disposition. Results from the formal evaluation of this intervention are currently being monitored and collected and will be presented elsewhere.

ROLE OF CBPR AND EM TRAINEES IN ADDRESSING HEALTH DISPARITIES

EDs are key players in local social safety nets and must have open lines of communication with other actors in that safety net. EM trainees can play an important role in developing and maintaining these partnerships. Our project focused on: (1) involving ourselves in the city response for PEH, (2) developing better testing protocols for PEH and referral pathways within the ED, and (3) dynamic provider education. Through this intervention, we provided safer and better care for PEH, the city more effectively contained spread among a vulnerable population, and we exemplified a model of EM trainees tackling health disparities within their local community.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has outlined health quality pathways in the clinical learning environment to address health disparities, many of which are illustrated in our process (Table 1).30 CBPR is particularly well suited to provide trainee education in this scenario because it allows experiential learning for trainees to work with and understand a diverse group of stakeholders, deepen their knowledge of local health disparities, develop and implement interventions to improve care, lead research measuring their outcomes, and bridge the divide between the community and clinical setting.

| ACGME health quality pathway item30 | CBPR key principles15 | Examples from CBPR Homelessness Task Force |

|---|---|---|

| Engages residents, fellows, and faculty members in defining strategies and priorities to eliminate health care disparities among its patient population. |

Recognizes community as a unit of identity. Addresses health from both positive and ecological perspectives. Promotes a co-learning and empowering process that attends to social inequalities. |

CBPR group centered the voices of PEH and community service providers to identify research and intervention priorities that resonate with the affected population. The priority of an ED referral pathway was shared among community service providers and elected officials. |

| Provides opportunities for residents, fellows, and faculty members to engage in interprofessional quality improvement projects focused on eliminating health care disparities among its patient population. |

Builds on strengths and resources within the community. Facilitates collaborative partnerships in all phases of the research. |

Our interprofessional CBPR group included: ED providers, social workers, care coordinators, street medicine and community health providers, local advocates, elected officials, and people with lived experience of homelessness. Project focused on addressing COVID health disparities among PEH. |

| Maintains a process that informs residents, fellows, and faculty members on the clinical site's process for identifying and eliminating health care disparities. |

Involves a cyclical and iterative process. Integrates knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners. |

Unifying the shared priorities of the community organizations, PEH, and the ED administration into one protocol. Trainees learned from leading the design of the protocol through to implementation. |

| Identifies and shares information with residents, fellows, and faculty members on the social determinants of health for its patient population. | Disseminates findings and knowledge gained to all partners. | Trainee-led dissemination of PEH COVID housing protocol throughout the emergency department with ongoing education of and raising awareness among faculty, co-residents, and staff. |

- Abbreviations: ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; CBPR, community-based participatory research; PEH, people experiencing homelessness.

CONCLUSION

As one of the primary points of contact in the health care system, the ED’s obligation to people experiencing homelessness necessitates a reexamination of the new normal brought to us by COVID-19. This landscape will continue to change as the pandemic evolves via public health intervention, additional viral waves, and vaccination rollouts. As the crisis of homelessness is reflected within our EDs and exacerbated by the pandemic, emergency medicine trainees have a unique ability to intervene with impact and should take action to counteract systemic inequities impinging on the health of people experiencing homelessness and other vulnerable populations. This project shows that trainees working in partnership with the community can effectively ensure that dynamic information pipelines keep providers abreast of community changes. It demonstrates the capacity of community-based participatory research to support trainees to develop up-to-date and relevant departmental policies ensuring that resources for people experiencing homelessness are used appropriately and discharges are safe. Engaging community-based participatory research methods to address local health disparities not only directly educates trainees, such projects also allow dissemination of the results throughout residency programs to raise awareness of these disparities and set examples of collaborative interventions. Improving care in the ED for this population is central to ensuring that the homelessness crisis in the era of COVID-19 is not worsened. As trainees, we have the potential through local engagement to develop systemic interventions and community partnerships to build toward a more just and equitable health care system.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Caitlin R. Ryus is the co-leader of the CBPR and task force described in the paper. She was involved in the conception, design, and implementation of the described policy and conception and drafting of the manuscript. David Yang was responsible for conception and drafting of the manuscript. Jennifer Tsai: was responsible for drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. Jonathan Meldrum is the co-leader of the CBPR and task force described in the paper. He was involved in the conception, design, and implementation of the described policy and provided critical revision of the manuscript. Christine Ngaruiya serves as the faculty mentor and advisor for the CBPR team. She was involved in the conception, design, and implementation of the policy described and provided critical revision of the manuscript.