SNAP online purchasing and the healthfulness of food purchases

This research was supported by a Cooperative Agreement (58-4000-3-0092) with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service. The findings and conclusions in this presentation are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. The analysis, findings, and conclusions expressed in this presentation should not be attributed to Circana (formerly IRI).

Editor in charge: Keenan Marchesi

Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot expansion (SNAP OPP) on SNAP households' online grocery shopping behaviors and the healthfulness of their food-at-home purchases. We explore quasi-experimental estimates of the impact of online purchasing by leveraging a unique natural experiment: the staggered introduction of the SNAP OPP across US states. The analysis combines data on household food-at-home purchases around the time of the policy expansion with a dynamic difference-in-differences empirical strategy. The results indicate that the SNAP OPP increased the frequency of online grocery shopping, associated spending, and the healthfulness of food-at-home purchases among SNAP households.

Online grocery purchasing, by which consumers purchase groceries online for home delivery or at-store pickup, grew relatively slowly in the United States prior to 2020. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated its adoption as social distancing restrictions were put in place and consumers sought to avoid in-person contact to minimize the chance of contagion. Rates of online grocery shopping remained elevated into 2021 and 2022, suggesting a lasting shift in consumer behavior beyond the pandemic (Brenan, 2022).

As part of its response to the pandemic, the USDA Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) expanded the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot (OPP), which allows SNAP recipients to redeem their benefits online at authorized, participating retailers. The pilot was originally planned to roll out to eight states across 2019 and 2020. With the heightened need for social distancing and other obstacles to in-person food access, FNS worked with states mid-rollout to quickly expand OPP to additional states beyond the initial scope. By the end of May 2020, OPP was in place in 25 states and Washington DC, with 21 more following by September 2020 and the last states adopting the program by June 2023, enabling virtually all SNAP participants to purchase groceries online (Jones & Toossi, 2024). Program usage increased over time, with the share of SNAP and Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) benefits redeemed online increasing steadily from about 1% midway through 2020 to about 9% near the end of 2023 (Jones & Toossi, 2024).

SNAP OPP represents a unique expansion to low-income food access during a critical period, but expanding online purchasing also has the potential to transform grocery purchasing in the future. Research consistently shows that SNAP households tend to have lower diet quality compared to non-SNAP households (Gleason et al., 2021). SNAP participants generally consume fewer fresh fruits and vegetables while purchasing more processed foods, often due to economic constraints and limited retail options. Vulnerable populations, such as older adults, racial and ethnic subpopulations, households with children, or those living in remote areas, often face additional barriers to accessing healthy foods (Gundersen, 2022; Hales & Coleman-Jensen, 2024). For example, older adults may experience physical limitations or reduced mobility that limit their ability to visit grocery stores, while households with children often face financial and time constraints. Expanding online grocery options could help reduce some of these challenges.

Online grocery shopping could help promote healthier purchases by addressing these barriers. First, in areas where brick-and-mortar stores sell predominantly non-perishable options, online options could introduce access to fresh fruits and vegetables (Bennett et al., 2024; Gundersen, 2022). For example, online grocery platforms could provide a wider variety of fresh vegetables sourced from more stores in the consumer's region, rather than just the inventory of a single neighborhood store, which can expose consumers to potentially higher-quality fresh food options, especially those consumers facing high transportation costs. Second, online grocery shopping could promote planning and budgeting of food purchases or make relevant information more salient in ways that promote healthier food choices (Bennett et al., 2024; Davydenko & Peetz, 2020). Behavioral economics suggests that distance from impulse purchases could reduce the purchase of unhealthy foods, and proposals to encourage the selection of healthier foods in SNAP have included allowing recipients to commit benefits to more nutritious selections in advance (Richards & Sindelar, 2013). Previous research finds that, following the introduction of a retailer's online shopping service, online shopping baskets contained more healthful foods, suggesting the potential of online purchasing to alter consumer behavior (Harris-Lagoudakis, 2022). In addition, online grocery platforms may offer discounts, coupons, and price comparisons that enable consumers to make more informed and cost-effective choices, helping fresh vegetables compete more favorably against less nutritious options. Further, online shopping algorithms could play a role in recommending healthy or unhealthy foods, analogously to marketing in brick-and-mortar stores, which could influence consumer food choices (Brandt et al., 2019). Although evidence suggests disparities in access to healthy options via SNAP online purchasing may exist in rural and/or high-poverty areas (Brandt et al., 2019; McGuirt et al., 2022), online grocery purchasing has the potential to enhance food access for SNAP beneficiaries (Martinez et al., 2018).

Despite this potential, there has been limited research on the implementation of SNAP OPP and its impacts on SNAP participants. Prior research has focused largely on identifying the challenges of implementing the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot and recipient attitudes potentially inhibiting adoption (Brandt et al., 2019; McGuirt et al., 2022; Rogus et al., 2020). Jones et al. (2023) exploit the rapid state-level expansion of SNAP OPP to estimate the short-term impacts of access to the pilot on food sufficiency among low-income families with a two-way fixed effects model. They find that the OPP decreased food insufficiency among low-income adults by 2 percentage points. G. C. Davis, Pierce, et al. (2025) further show that time savings from online grocery shopping contribute to improvements in the implicit welfare of SNAP participants.

Given the ongoing investment in expanding SNAP online shopping, there is growing interest in understanding its impacts. Online grocery shopping has the potential to promote the healthfulness of food purchases, aligning with broader policymaker goals to improve nutrition among SNAP recipients. This paper aims to investigate the effects of access to SNAP online purchasing on the online grocery shopping behaviors of SNAP households and the healthfulness of their food-at-home purchases. Using data from the Circana Consumer Network spanning 2018 to 2021, we explore quasi-experimental estimates of the impact of SNAP OPP by leveraging a unique natural experiment: the staggered state-level introduction of the pilot. Using data on household food-at-home purchases and where these purchases are made, we construct measures representing household use of online grocery shopping, including the propensity to shop online and the shares of expenditures or grocery trips made online. We also construct “USDA score” measures representing household food-at-home purchase alignment with USDA dietary recommendations. Combining these measures with information on household characteristics and the timing of state OPP adoption, we implement a fully dynamic difference-in-differences empirical strategy to estimate the heterogeneous impact of SNAP OPP on online grocery shopping utilization and purchase healthfulness among SNAP households across different treatment cohorts and over time (Callaway & Sant'Anna, 2021).

Our results show significant increases in all measures of online grocery shopping usage following state OPP implementation, confirming a notable shift in consumer behavior toward utilizing online platforms for grocery shopping. Further, the expansion of SNAP OPP contributed to improvements in the overall nutritional quality of food purchases, as indicated by changes in the constructed USDA score measure. We also find that these impacts are driven by promoting healthier food purchases, bringing purchases of more healthful food categories closer to USDA-recommended levels. Moreover, SNAP OPP expansion has impacts immediately after implementation, and its impacts continue over time. Overall, the findings of this study underscore the potential for SNAP online purchasing options to alter grocery shopping behaviors and the healthfulness of food-at-home purchases among SNAP households. These results provide valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders seeking to enhance the effectiveness of SNAP and related programs or to promote healthier food choices.

DATA

The SNAP online purchasing pilot rollout

The 2014 Farm Bill instructed USDA to pilot online SNAP benefit redemption in a variety of retailer settings. Under the SNAP OPP, participants can redeem their benefits online for groceries with participating, authorized retailers and receive their groceries through pickup at a brick-and-mortar location or have them delivered to their home, much like online grocery shopping works using a debit or credit card. However, SNAP benefits cannot be used for purchase-related tips or fees, and as is the case in brick-and-mortar stores, benefits generally cannot be redeemed for hot or prepared foods, alcohol, or non-food items. For the initial pilot phase, USDA selected eight retailers in eight states to include a variety of business models and geographical contexts. The rollout began in April 2019 with New York; Washington in January 2020; and Alabama, Oregon, and Iowa in March 2020 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, 2024). The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic led USDA to open the OPP to the remaining states not part of the initial pilot, with the first of these states implementing the pilot in April 2020. This led to a substantial increase in the number of participating states, particularly throughout 2020, but also in 2021–2023.

We received information on the date of OPP implementation in each state and Washington DC from the USDA Food and Nutrition Service.1 We note that our focus on the introduction of the OPP in each state does not capture within-state expansions to additional retailers. Unfortunately, we lack reliable information on the timing of retailer OPP participation in each state, but we do note that certain online retailers were available in almost all states at the time of program introduction.2 We also note that almost all states applied to join the pilot in the first few months after its expansion, but—importantly—the timing of its introduction in each state was influenced by administrative factors. These included the order in which USDA received state applications as well as technological and administrative factors within each state, including the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) processor with which a state contracted and the speed with which processors made the system updates needed to allow secure online benefit redemption (Jones et al., 2023). Those states that shared an EBT processor tended to have system updates made at similar times, meaning they tended to be able to join the pilot at similar times (Jones et al., 2023).

Circana consumer network

We use Circana (formerly IRI) Consumer Network data spanning 2018 to 2021 to analyze household food purchases, focusing on online grocery shopping by US households before and after the expansion of the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot during the pandemic. The Circana Consumer Network household-based scanner data is a longitudinal panel that provides detailed information on household purchases organized by shopping trip, including products bought, prices, quantities, and the time and location of purchases. On average, our sample includes around 78,878 unique households each month during our sample period, and we include data covering the 6 months before and the 20 months after the SNAP OPP implementation in each state.

We classify a trip as an online grocery shopping trip if it is documented as occurring on an identified online retailer website, including both retailers with brick-and-mortar stores and online-only grocery platforms. The classification includes both home delivery and curbside pickup transactions, as the data do not distinguish between these fulfillment methods. However, because all identified transactions were conducted on an online platform, they represent a shift from in-store shopping behavior to an online ordering process. Furthermore, to refine our definition of online grocery shopping, we also check for the presence of perishable food item purchases (e.g., dairy, frozen meat, vegetables) in each trip. This additional criterion helps ensure that our analysis focuses on meaningful grocery purchases rather than non-food or household items that might also be bought online. The data also includes information on household characteristics, including whether a household reported SNAP receipt in the June survey of the corresponding year,3 which we use to construct the primary analysis sample of SNAP households.4 We use information on state of residence to assign households to OPP treatment status, and we use information on household size and income in some supplementary analyses.

To provide a comprehensive view of the extent and nature of online grocery shopping among households, multiple measures were used to characterize households' online grocery shopping behaviors, including (1) propensity: whether a household has done online grocery shopping at least once in a month; (2) expenditure share: the proportion of online grocery expenditures relative to households' total grocery shopping expenditures across all channels in a month; and (3) trips share: the share of online grocery shopping trips among all grocery shopping trips in a month. Table 1 provides summary statistics for these online grocery shopping measures for the full sample, as well as for SNAP and non-SNAP households. Despite its rapid recent growth, the average propensity for online grocery shopping, based on household-month-level observations, was 2.68% across all households. This propensity was higher among SNAP households, with a mean of 4.07%, compared to 2.61% for non-SNAP households. Across all households and months, only 1.27% of all grocery expenditures were made online, with a substantial standard deviation of 9.32%. SNAP households exhibit a higher mean expenditure share of 2.00%, compared to 1.23% for non-SNAP households. Around 1.08% of grocery trips were made online among the full sample. SNAP households had a slightly higher mean of 1.59% while non-SNAP households had a mean of 1.05%.

| Full sample | SNAP | Non-SNAP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. dev. | Mean | Std. dev. | Mean | Std. dev. | |

| Online grocery shopping | ||||||

| Propensity to shop online | 0.0268 | 0.1614 | 0.0407 | 0.1975 | 0.0261 | 0.1594 |

| Online expenditure share | 0.0127 | 0.0932 | 0.0200 | 0.1166 | 0.0123 | 0.0918 |

| Number of trips share | 0.0108 | 0.0812 | 0.0159 | 0.0970 | 0.0105 | 0.0803 |

| Healthfulness of food-at-home purchases | ||||||

| USDA score | 5.5738 | 2.7691 | 5.0631 | 2.5921 | 5.5993 | 2.7752 |

| Healthy subscore | 15.0774 | 5.5420 | 14.2987 | 4.9427 | 15.1163 | 5.5674 |

| Unhealthy subscore | 12.3481 | 16.1915 | 10.8587 | 15.1326 | 12.4224 | 16.2389 |

| Observations | 2,108,476 | 109,376 | 1,999,100 | |||

EMPIRICAL MODEL

The canonical DID model typically deals with two periods and a common treatment date. With staggered treatment design, bias can result from applying a standard, two-way fixed effect (TWFE) regression estimator (Callaway & Sant'Anna, 2021; Goodman-Bacon, 2021; Sun & Abraham, 2020). Specifically, the treatment effect estimate obtained from a TWFE model is a weighted average of all possible 2 X 2 DID comparisons between groups of units treated at different points in time (Goodman-Bacon, 2021). Therefore, if treatment effects are heterogeneous across groups or time, the TWFE estimator does not deliver consistent estimates for the average treatment effects on the treated group (ATT). We address this concern by extending the standard DID technique to a fully dynamic DID with multiple time periods, variation in treatment timing, and treatment effect heterogeneity. Following Callaway and Sant'Anna (2021), the core of this analysis relies on separating the DID analysis into three separate steps: (1) identification of policy-relevant disaggregated causal parameters; (2) aggregation of these parameters to form summary measures of the causal effects; and (3) estimation and inference about these different target parameters.

We first estimate the effects of all treatment groups across all observed periods. The treatment group is composed of SNAP households who lived in a state that adopted SNAP OPP before the end of the sample periods. We use “never-treated” households as the control group, denoted by . These include (1) non-SNAP households and (2) households who live in states that do not adopt SNAP OPP before the end of the sample period. We further conduct robustness analysis using two different measures for the control group—low-income (<130% federal poverty line) but non-SNAP households, and SNAP-eligible but non-SNAP households.

The first term on the right side of this equation indicates the change for cohort and the second term represents the change for never-treated households. The group-time average treatment effects are nonparametrically identified and estimated using the doubly robust (DR) estimator based on inverse probability of tilting and weighted least squares (Sant'Anna & Zhao, 2020). For each disaggregated causal parameters estimation, we exploit the panel features of our data and include household fixed effects, state fixed effects, and month-year fixed effects as controls. In addition, we include a dummy variable for the presence of a COVID stay-at-home order in a state to capture potential relationships with online grocery shopping.

RESULTS

Online grocery shopping behaviors

We first report the mean average treatment effect of the SNAP OPP rollout across all treatment groups and observed periods on several key online grocery shopping-related outcomes in Column 1 of the upper panel of Table 2. On average, we find positive and statistically significant increases in the propensity to shop online, the share of grocery expenditures made online, and the share of grocery shopping trips occurring online among SNAP households. On average, the implementation of the OPP in a state increases the probability of shopping online by 1.01 percentage points, the online expenditure share by 0.8 percentage points, and the online trip share by 0.55 percentage points. Together, these findings indicate that the state-level expansion of access to online grocery purchasing with SNAP benefits did lead to corresponding increases in utilization.

| Main model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Different measure of treatment group | 2. Different measure of control group | 3. Additional control | 4. Excluding P-EBT | |||||

| Low-income (<130%FPL) | SNAP-eligible | Households identified as SNAP participants based on EBT payments | Low-income (<130%FPL) but non-SNAP households. | SNAP-eligible but non-SNAP households. | Emergency allotments | Households without school-aged children (under 18) | ||

| Dependent variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

| Online grocery shopping | ||||||||

| Propensity to shop online | 0.0101*** | 0.0022 | 0.0014 | 0.0109*** | 0.0121*** | 0.0129** | 0.0097*** | 0.0085** |

| (0.0033) | (0.0017) | (0.0015) | (0.0031) | (0.0046) | (0.0042) | (0.0035) | (0.0039) | |

| Online expenditure share | 0.0080*** | 0.0018* | 0.0017** | 0.0083*** | 0.0084*** | 0.0088*** | 0.0081*** | 0.0066*** |

| (0.0019) | (0.0010) | (0.0008) | (0.0017) | (0.0027) | (0.0025) | (0.0020) | (0.0023) | |

| Online trips share | 0.0055*** | 0.0012 | 0.0014** | 0.0057*** | 0.0056** | 0.0064*** | 0.0055*** | 0.0042** |

| (0.0016) | (0.0008) | (0.0007) | (0.0014) | (0.0023) | (0.0021) | (0.0017) | (0.0019) | |

| Healthfulness of food-at-home purchases | ||||||||

| USDA score | 0.1138*** | 0.0478** | 0.0379** | 0.0882*** | 0.1378*** | 0.1395*** | 0.1158*** | 0.1015*** |

| (0.0338) | (0.0211) | (0.0190) | (0.0317) | (0.0442) | (0.0420) | (0.0347) | (0.0380) | |

| Healthy subscore | 0.2975*** | 0.1064** | 0.0880** | 0.2496*** | 0.3561*** | 0.3314*** | 0.3041*** | 0.2744*** |

| (0.0704) | (0.0440) | (0.0397) | (0.0652) | (0.0912) | (0.0860) | (0.0724) | (0.0800) | |

| Unhealthy subscore | 0.2615 | 0.1468 | 0.1523 | 0.2588 | 0.2946 | 0.2198 | 0.2610 | 0.1963 |

| (0.2051) | (0.1306) | (0.1150) | (0.1850) | (0.2542) | (0.2657) | (0.2126) | (0.2551) | |

| Observations | 2,108,476 | 2,108,476 | 2,108,476 | 2,108,476 | 2,108,476 | 2,108,476 | 2,108,476 | 1,562,849 |

- Note: (1) The treatment group for the main model includes SNAP households living in states that adopted SNAP OPP before the end of the sample period, and the control “never-treated” group includes non-SNAP households as well as SNAP households living in states that did not adopt SNAP OPP during the sample period; (2) ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1; (3) Columns 2–4 present robustness checks using alternative definitions of the treatment group. In Column 2, the treatment group consists of households with incomes below 130% of the Federal Poverty Level (<130% FPL). Column 3 defines the treatment group as households that are approximated as eligible in their state based on their gross income. Column 4 considers households identified as SNAP participants based on Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) payments. Columns 5 and 6 provide robustness checks with different control groups redefined to include SNAP households living in states that did not adopt SNAP OPP before the end of the sample period as well as either non-SNAP households with income <130% FPL in Column 5 or non-SNAP households approximated as eligible based on gross income in Column 6. Column 7 represents an additional control for emergency allotments. Column 8 presents an analysis excluding P-EBT, focusing on households without school-aged children (under 18 years old).

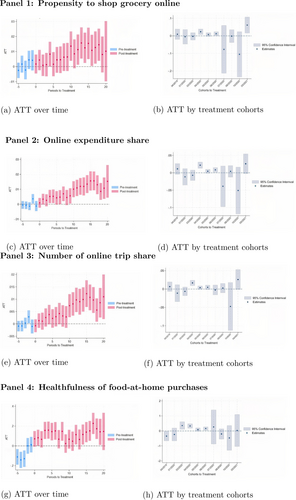

We then examine the average treatment effect over time and by treatment cohort. Figure 1a,c,e presents the effects of SNAP OPP introduction on online grocery shopping behaviors over time. The pre-treatment period is plotted in blue, and the post-treatment period is plotted in red. The 95% confidence intervals (shaded areas) around the ATT estimates indicate the statistical significance of the results. Figure 1b,d,f presents the average treatment effect by treatment cohort and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Panel 1 of Figure 1 focuses on the propensity to shop grocery online. As shown in Figure 1a, the ATT remains close to zero in the pre-treatment period, indicating no significant changes before the SNAP OPP was implemented and confirming the parallel trend assumption of our model. However, there is a noticeable increase in average treatment effect shortly after the treatment period begins, which continues to rise steadily over time. The consistent upward ATT indicates that SNAP OPP has a growing positive impact on consumers' propensity to shop for groceries online grocery shopping and the effect of the treatment becomes stronger as time progresses. Figure 1b plots the average treatment effects by treatment cohort. The ATT varies across different cohorts, indicating heterogeneous effects of the SNAP OPP depending on when it was implemented. Some cohorts at the beginning of the pandemic experience more positive effects, such as the April and June 2020 cohorts, while others show insignificant impacts.

Panels 2 and 3 of Figure 1 focus on the other two measures of online grocery shopping, the share of grocery expenditures made online and the share of grocery trips made online. The results are similar to those from the analyses of the propensity to shop for groceries online. In general, the rising ATT post-treatment highlights a significant shift in SNAP households' behavior toward online grocery shopping. The sustained positive ATT indicates that the increase in the online shares of expenditure and trips is not a temporary change but a lasting one, suggesting that SNAP households continue to prefer online grocery shopping after the initial adoption period. Similarly to the results on the propensity to shop for groceries online, the ATT varies significantly across different cohorts, which indicates heterogeneous responses to the SNAP online purchasing expansion across different cohorts. The differences observed between the April–June 2020 cohort and later (July 2020 and beyond) SNAP OPP cohorts could stem from multiple factors, including the timing of program implementation, variations in public health messaging, and broader economic and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. First, SNAP OPP implementation varied across states, and the extent to which states promoted online purchasing options to SNAP recipients likely differed. Early adopters may have benefited from stronger outreach efforts, increased urgency to use online shopping during the peak of the pandemic, or greater initial media attention. Second, the early pandemic period (April–May 2020) was marked by significant disruptions in grocery shopping habits, supply chain issues, and heightened health concerns. Many consumers, including SNAP households, turned to online shopping out of necessity. Households adopting online grocery shopping early may have been more motivated to explore healthier food options due to greater uncertainty about food availability, reliance on meal planning, or increased health awareness prompted by COVID-19 concerns. By July 2020, some of these pressures may have subsided, leading to differences in purchasing behavior between early and later cohorts.7

Healthfulness of food-at-home purchases

We report the mean average treatment effect of SNAP OPP on the healthfulness of food-at-home purchases, as represented by the overall USDA score measure which indicates alignment with USDA recommendations, in Column 1 of the lower panel of Table 2. Specifically, the implementation of the OPP in a state increases the USDA score by 0.1138 units, indicating an increase in the overall nutritional quality of the food purchased for home consumption.

Figure 1g presents the ATT of SNAP OPP on the healthfulness of food-at-home purchases over time. The ATT for the healthfulness of food purchases remains close to zero before the SNAP online purchasing expansion, indicating no significant change in healthfulness among SNAP households during the pre-treatment period. The ATT in post-treatment, however, shows a general upward trend, indicating a positive impact of the SNAP OPP on the healthfulness of food purchases. The treatment effects increase gradually and remain positive, suggesting sustained improvement over time. The confidence intervals indicate that most post-treatment ATT values are statistically significant. While prior research finds that overall dietary quality in the United States temporarily improved in the early pandemic months before reverting to pre-pandemic levels (Simandjuntak et al., 2024), our results suggest that SNAP OPP contributed to more sustained shifts in online grocery shopping and healthier food purchases among SNAP households. The continued positive effects over time indicate that SNAP OPP may have played a role in reinforcing long-term improvements in food purchasing behaviors, rather than merely reflecting temporary pandemic-driven adjustments.

We further examine the impacts of the SNAP OPP on food purchase healthfulness by considering models using the healthy and unhealthy USDA subscores we construct (focusing on healthier or unhealthier food categories) as outcomes. This allows us to broadly investigate the sources of the improvement in the healthfulness of food purchases and identify whether changes in the USDA score are driven primarily by healthy or unhealthy food expenditures. We report the mean ATT of SNAP OPP introduction on the healthy and unhealthy subscores in Column 1 of the lower panel of Table 2. The ATT on the healthy subscore is 0.2975, indicating that SNAP households' purchases aligned more closely to USDA recommendations in these categories following OPP introduction. This represents a notable increase of approximately 2.0% relative to the mean healthy subscore for healthy categories (15.08). The ATT for the subscore concentrating on less-healthy food categories is 0.2615. The positive coefficient estimate would signify closer alignment among SNAP households to USDA recommendations in these categories; however, this estimate is statistically insignificant. Taken together, these findings suggest that access to SNAP online purchasing leads participants to increase the overall healthfulness of their food-at-home purchases primarily by adjusting their purchasing habits to better align with USDA recommendations related to healthier foods.

Robustness analyses

We conduct additional analyses to test the robustness of our main findings. One potential source of measurement error could be the misreporting of SNAP receipt among households in the data (Gregory, 2025). To address this, we consider three alternative definitions of the treatment group. Instead of households reporting SNAP receipt, these models include as the treatment group: (1) households imputed as SNAP income-eligible based on having income below the federal gross income limit of 130% of the federal poverty level (FPL); (2) households imputed as income-eligible based on having income below the gross income limit in place in their specific state (ranging from 130% to 200% FPL); or (3) households identified as SNAP participants based on federal income eligibility and use of EBT to pay for groceries during the month. The results, presented in Columns 2–4 of Table 2, remain highly consistent with those from the main model in Column 1 in terms of sign and overall magnitude, reinforcing the validity of our estimates. While the findings using the first two alternative definitions of SNAP participation exhibit somewhat lower magnitudes and reduced statistical significance, this is expected, as these models broaden the treatment group to include households that are technically eligible for SNAP but may not be actively participating. Since non-treated households do not experience the benefits of the SNAP OPP, their inclusion in the sample dilutes the overall effect observed in the treatment group. In general, the consistency across different definitions underscores the robustness of SNAP OPP's impact on the outcomes. In our main model, we use as the “never-treated” group those households who do not report participation in SNAP and households who report participation but live in states that do not adopt SNAP OPP before the end of the sample period. Including all non-SNAP households may potentially introduce high-income households into the control group, who could have different shopping behaviors and access to online platforms compared to low-income SNAP households. This may raise potential concerns about the comparability between the treatment and control groups. To mitigate these concerns, we consider alternate models in which the control group is redefined to include SNAP households in states not adopting SNAP OPP before the end of the sample period as well as either (1) those households with incomes below 130% FPL but who do not report participation in SNAP; or (2) those households with incomes below the gross income limit for SNAP in their state but who do not report participation in SNAP. The results are presented in Columns 4 and 5 of Table 2. We observe that the results are generally consistent with the primary results in sign, magnitude, and statistical significance, further underscoring the robustness of our findings.

To further validate our findings, we conducted two additional robustness checks. First, we control for the issuance of SNAP emergency allotments (EA), which were temporary increases in SNAP benefits provided during the COVID-19 pandemic. EA issuance was implemented at different times across states, and observed changes in grocery shopping behavior could be partly driven by increased benefit amounts. After incorporating an indicator for the state-month-level issuance of EA as a control, our results in Column 7 of Table 2 remain consistent with the main model, reinforcing that SNAP OPP had an independent effect beyond just changes in benefit amounts. Second, we conduct a robustness check by excluding households with children, thereby removing those who may have received Pandemic-EBT (P-EBT) benefits, which was a temporary federal program that provided food assistance to families with children who lost access to free or reduced-price school meals due to school closures. Because P-EBT benefits were distributed through EBT cards, some recipients may have misreported as SNAP participants, potentially biasing our treatment group (Bauer et al., 2024). The results in Column 8 of Table 2 remain consistent after excluding these households. Together, these robustness checks strengthen the credibility of our results by ensuring that our findings are not driven by other pandemic-related policy interventions and further confirming that SNAP OPP played a meaningful role in shaping purchasing behaviors and improving dietary quality.

Heterogeneity in treatment effects

To examine the heterogeneous impact of SNAP OPP, we conduct subsample analyses based on household characteristics, and the results are presented in Appendix Table A1.8 We first analyze the treatment effect for households with members over 65 years old and those eligible for WIC benefits (Columns 1 and 2). Although other studies have found lower utilization of online grocery shopping among the older adult population (e.g., W. Davis, Jones, et al., 2025), the results indicate that SNAP OPP increases online grocery shopping participation and expenditure share among SNAP participants aged over 65. Additionally, older adults experience a notable improvement in the healthfulness of their food purchases, as indicated by significant increases in the USDA score and the healthy subscore. SNAP OPP may impact this population in particular due to mobility constraints and health-conscious purchasing behaviors. For WIC-eligible households, the results are less pronounced, with no significant effects detected across most outcomes. This may be due to the small sample size (1.83% of the dataset), or because WIC imposes additional constraints on food choices and its benefits cannot be redeemed online, limiting these households' ability to fully make use of online purchasing options under SNAP OPP.

Columns 3–7 examine treatment heterogeneity across racial (White, Black, and Asian/other) and ethnic groups (Hispanic and non-Hispanic) of the household respondent. In general, we estimate impacts of larger magnitude for Black households of SNAP OPP on the online grocery shopping utilization outcomes. When comparing Hispanic and non-Hispanic households (Columns 6 and 7), we find that non-Hispanic households show significant increases in online grocery shopping, but we do not find corresponding evidence of increases among Hispanic households. This could reflect differences in household composition, digital literacy, or regional variations in SNAP OPP adoption and retailer participation. In terms of healthfulness of purchases, we find evidence that OPP implementation increases the USDA scores and healthy subscores of White households and weaker, mixed evidence of increases among Black households. We estimate larger impacts among Asian/Other and Hispanic households on only the healthy subscore. This suggests that the impacts of SNAP OPP extend across different racial and ethnic groups, with some evidence of varying impacts on online purchasing use and dietary quality.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The paper investigates the effects of the state-level expansion in access to online purchasing via the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot on both the online grocery shopping behaviors and the healthfulness of food-at-home purchases among SNAP households. By combining data on household food-at-home purchases around the time of the policy expansion with a fully dynamic difference-in-differences empirical strategy, we estimate the heterogeneous impact of SNAP OPP across different treatment cohorts, subsamples, and over time. The results show a significant increase in online grocery shopping utilization following the expansion of SNAP OPP, suggesting the potential for impacts on other consumer behaviors, such as foods purchased. Furthermore, the expansion of SNAP OPP was associated with improvements in the nutritional quality of food purchases, as indicated by an increase in the USDA score measure. A closer examination reveals that these improvements were primarily driven by closer purchase alignment to USDA-recommended levels of a subset of healthier food categories.

These findings have potential implications for policymakers and stakeholders involved in public health and welfare programs. First, the significant increase in propensity to shop online and the share of grocery expenditure and trips made online among SNAP households indicates a clear behavioral shift toward utilizing online grocery shopping. Despite initial concerns or hesitation toward shopping for groceries online (e.g., Rogus et al., 2020), SNAP households used online purchasing following pilot expansion and continued to do so. This finding is corroborated by the continued growth in online benefit redemption beyond the early pandemic period (Jones & Toossi, 2024). This suggests that increasing accessibility to online purchasing options effectively alters consumer behavior. Future studies could provide evidence on how SNAP populations use online benefit redemption to address food access challenges or which kinds of SNAP households use online shopping to a greater extent to better inform policymakers considering ways to expand food access via SNAP online purchasing. Second, we find evidence that the OPP rollout increased the overall healthfulness of food-at-home purchases made by SNAP households. The sustained positive average treatment effects over time suggest that changes in online grocery shopping behaviors and the healthfulness of food purchases could last beyond the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. If online purchasing with SNAP benefits does improve the nutritional quality of purchases, SNAP OPP could be a policy tool for promoting healthy food choices among SNAP populations.

Several potential explanations could account for the relationship between online SNAP purchasing access and food purchase healthfulness. First, online grocery platforms can make certain information more salient to consumers, like nutrition facts, customer reviews, and product comparisons. This could help SNAP households purchasing groceries online make better-informed and potentially healthier food choices. Online shopping also removes consumers from direct contact with the brick-and-mortar shopping environment. Physical distance from unhealthy foods and their associated in-store marketing could reduce impulse purchases of these foods. Relatedly, online shopping could make it easier to plan and review purchases. If consumers tend to plan healthier purchases than they actually make when shopping in-store, online shopping access could allow SNAP households to follow their plans more closely. It could also be easier to remove unhealthy items from an online shopping cart than a physical one if a consumer rethinks their decision to purchase these items.

Additionally, online platforms can provide a wider array of food choices than brick-and-mortar stores, especially in areas with limited food access. This expanded availability may have allowed SNAP households to purchase healthier food items that were previously inaccessible or harder to find. Moreover, online shopping platforms frequently use algorithms to recommend products based on previous purchases and browsing behavior. It is possible these product suggestions and nudges could promote healthy food purchases or reinforce previous purchases of these foods, though it is also possible they could promote unhealthy foods. Finally, the expansion of SNAP OPP occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when many people, including SNAP recipients, could have become more health-conscious given the heightened awareness of public health. This could have amplified the impacts of the OPP rollout on the healthfulness of food purchases among SNAP households.

Our findings highlight the impact of expanding SNAP online purchasing options on both online grocery shopping behaviors and the healthfulness of food-at-home purchases among SNAP households, underscoring the potential of online grocery shopping to enhance food access and improve dietary choices, both during the emergency context of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. However, further research to identify the causal mechanisms driving these changes could be useful. Such research would offer a stronger foundation for policymakers to make informed decisions about the future of SNAP online purchasing and its potential to enhance dietary outcomes among low-income populations.